SIBERIAN TIGERS

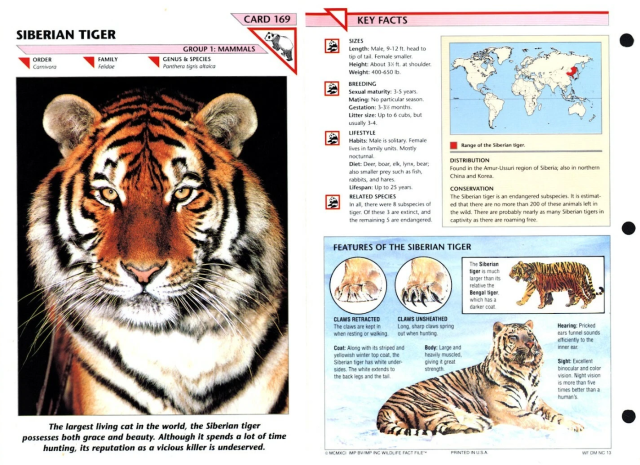

The Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) is the world's largest cat. Also known as the Amur tiger, Manchurian tiger and Korean tiger, it can weigh up to 363 kilograms (800 pounds). It is the only tiger that lives in the snow. Television naturalist David Attenborough called the Siberian tiger spectacularly large and said its large size is not unexpected because large size offers advantages in cold temperatures. [Source: Howard Quigley, National Geographic July 1993; Maurice Hornocker, National Geographic, February, 1997; Peter Matthiessen, The Independent, March 5, 2000]

Siberian tigers live in southern Primorsky in the Russian Far East (easternmost Siberia) in mixed coniferous and deciduous forests. Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Siberian tigers "are ocher and russet, with a pink nose, amber eyes and thick black stripes that band their bodies in patterns as unique as any fingerprint. An adult male Amur can measure as long as 11 feet and weigh 450 pounds; the average female is closer to 260. On the kill, an Amur will load its powerful back haunches and slam forward like the hammer of a revolver. To watch a tiger bring down a deer is to see its weight and bulk vanish.” [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 */]

The Siberian tiger is a subspecies of tiger (Panthera tigris). It is larger than the Bengal tigers and twice as large as other Asian tiger subspecies. Its thick coat makes it appear even larger. There around 400 to 500 left in the wild, mainly in the Primorye region of the Russian Far East — the largest continuous tiger population the world — and another 800 to 1,000 in captivity. India has more tigers than Russia but their population is broken up and fragmented.

The English name 'Siberian tiger' was coined by James Cowles Prichard in the 1830s. The name 'Amur tiger' was used in 1933 for Siberian tigers killed by the Amur River for an exhibition in the American Museum of Natural History. The Tungusic peoples who live the range of Siberian tigers considered tigers as near-deities and referred to them as "Grandfather" or "Old man". The Udege and Nanai people call them "Amba". The Manchu considered the Siberian tiger as Hu Lin, the king. The Siberian tiger is a national symbol of Korea and plays a central role in creation myth of the Korean people. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Siberian tiger is genetically close to the now-extinct Caspian tiger. Results of a phylogeographic study comparing mitochondrial DNA from Caspian tigers and living tiger populations indicate that the common ancestor of the Siberian and Caspian tigers colonized Central Asia from eastern China, via the Gansu−Silk Road corridor, and then subsequently traversed Siberia eastward to establish the Siberian tiger population in the Russian Far East The Caspian and Siberian tiger populations were the northernmost in mainland Asia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SIBERIAN TIGER BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com;

HUMANS, SCIENTISTS, CENSUSES AND SIBERIAN TIGERS factsanddetails.com;

SIBERIAN TIGER CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com;

SIBERIAN TIGERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

SIBERIAN TIGER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

TIGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, STRIPES, NUMBERS, HABITAT factsanddetails.com ;

TIGER BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, MATING AND CUB-RAISING factsanddetails.com ;

TIGERS ON THE HUNT: PREY, METHODS, SUCCESS RATIOS factsanddetails.com

Books: "Tigers in the Snow" by Peter Matthiessen (Harvill Press, 2000); “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, (1999); “The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival” by John Vaillant (Knopf, 2010)]

History of Siberian Tigers

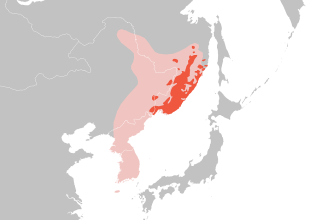

Siberian tigers once inhabited all of Korea and much of Manchuria, eastern China and Siberia, perhaps as far east as Mongolia and Lake Baikal. On the banks of the Amur River archeologist have discovered 6,000 year old depictions of tigers carved by the Goldis people. Now the Siberian tiger's range is limited to a 625-mile-long, 75-mile-wide, 60,000-square-mile strip of land in eastern Siberia near Vladivostok along the Pacific Ocean just north of North Korea. The heart of their range is the watershed of the Amur River and its tributary, the Ussuri, which forms the eastern border between Russia and China.

Decades of poaching and logging have ravaged the population of the Siberian tiger. Most Siberian tigers live in the 1,314-square-mile Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve, Ussuriski Reserve, Lazoski reserve and Kedrobaya Pad Reserve in the Far East. There are maybe scattered 20 individuals in northeastern China and North Korea. Five or six Siberia tigers have been counted in the Jilin Province in northern China.

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “ The Amur probably traces its lineage to an ur-species of Panthera tigris, which enters the fossil record about two million years ago. Over the ensuing millennia, nine distinct subspecies of tigers emerged, including the Bengal and the Amur. Each was an apex predator—the pinnacle of its region’s food chain. Unlike the bear, a formidable predator who feasts on both flora and fauna, the tiger is purely carnivorous, with a preference for ungulates such as deer and wild pigs; it will starve before consuming a plant. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 */]

“In the not-so-distant past, tigers roamed the shorelines of Bali, the jungles of Indonesia and the lowlands of China. But deforestation, poaching and the ever-widening footprint of man have all taken their toll, and today it is estimated that 93 percent of the ranges once occupied by tigers have been eradicated. There are few wild tigers remaining in China and none in Bali, nor in Korea, where medieval portraits showed a sinuous creature with a noble bearing and a nakedly hungry, open-mouthed leer—an indication of the mixture of dread and admiration humans have long felt for the beast. At the turn of the 20th century, it was estimated that there were 100,000 tigers roaming the wild. Now, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the number is probably much closer to 3,200. */

“In a way, the area comprised of Primorsky and neighboring Khabarovsk Province can be said to be the tiger’s last fully wild range. As opposed to India, where tiger preserves are hemmed in on all sides by the thrum of civilization, the Far East is empty and conspicuously frontier-like—a bastion of hunters, loggers, fishermen and miners. Just two million people live in Primorsky Province, on a landmass of nearly 64,000 square miles (about the size of Wisconsin), and much of the population is centered in and around Vladivostok—literally “the ruler of the east”—a grim port city that serves as the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the home base of WCS Russia.” */

Siberian Tigers Numbers

As of 2022, about 756 Siberian tigers including 200 cubs were estimated to inhabit the Russian Far East. As of 2014, about 35 individuals were estimated to range in the international border area between Russia and China. In 2005, there were 331–393 adult and subadult Siberian tigers in south-west Primorye Province in the Russian Far East. The population had been stable there for more than a decade because of intensive conservation efforts, but partial surveys conducted after 2005 indicate that the Russian tiger population was declining. An initial census held in 2015 indicated that the Siberian tiger population had increased to 480–540 individuals in the Russian Far East, including 100 cubs. This was followed up by a more detailed census which revealed there was a total population of 562 wild Siberian tigers in Russia. There are also hundreds of Siberian tigers in zoos and circuses and owned as "pets". [Source: Wikipedia]

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “A 1996 census of the Far East’s Amur population, using traditional snow-tracking methods and the expertise of area hunters and rangers, concluded that there were somewhere between 330 and 371 tigers in the region, and maybe 100 cubs.” In 2005, a team led by biologist Dale Miquelle did “a second census, which put the count at between 331 and 393 adults and 97 to 109 cubs. Miquelle believes the numbers may have dipped slightly in the few years afterwards, but he is confident that heightened conservation efforts, a more energetic defense of protected lands and improved law enforcement have now stabilized the population. A census planned for this winter should help clarify the numbers. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 */]

The shrinking numbers of Siberian tigers are the result of: 1) loss of habitat caused by the clear cutting of timber and illegal logging and mining; 2) poaching primarily for the folk medicine market in China; and 3) and decline in the numbers of animals that tigers feed on such as sitka deer, elk and wild boar. In the 20th century Siberian tiger numbers were reduced by hunters shooting adults for their skins and capturing cubs for zoos and circuses. In the 1930s Communist party leaders used to bag as many a ten tigers in one hunt. By the 1960s only about 30 of them were left.

Siberian tigers were well protected by the Soviet government. Borders were closed; there was strict gun control and tough penalties for poaching; foreigners were carefully watched, After a determined conservation effort the number of tigers increased to 400 during the mid 1980s. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, as salaries for conservationists disappeared, poaching increased. Their numbers fell back to around 200. In the early 1990s a string of bitter cold winters had an impact on tigers. Fires in eastern Siberia in 1998 linked to El Niño threatened their habitat. In recent years the number of tigers has been rising. Their numbers recovered to over 600 tigers.

Siberian Tiger Size and Lifespan

Siberian tiger average 3.14 meters (10 feet, 4 inches) in length (from nose to tip of tail), stand 1 to 1.1 meters (39 to 42 inches) at the shoulder and weigh 265 to 305 kilograms (585 to 676 pounds). A large male can measure four meters (13 feet) from tail to nose and weighs 362 kilograms (800 pounds).

Large verified wild Siberian tigers include a male captured by members of the Siberian Tiger Project. It weighed 206 kilograms (454 pounds). The largest radio-collared tiger (a male) weighed 212 kilograms (467 pound). The largest Siberian tiger recorded in captivity was a male named Jaipur, who weighed 423 kilograms (932 pounds) and was 3.32 meters (10.9 feet) long from nose to tail. He was owned by an American animal trainer, Joan Byron Marasek, according to Guinness World Records.

A wild male, killed in Manchuria by the Sungari River in 1943, reportedly measured 3.5 meters (11.7 feet) "over the curves", with a tail length of about one meter (3.25 feet). It weighed about 300 kilograms (660 pound). Unverified sources list weights of 318 kilograms (701 pounds) and 384 kilograms (847 pounds) and even 408 kilograms (899 pounds). In 2019, one of the largest Siberian tiger was recorded that was thought to weigh 384 kilograms (846.8 pounds) and measure over 3.4 meters (11 feet) from nose to tail. [Source: Wikipedia]

The average lifespan for Siberian tigers ranges from 16 to 18 years. Wild individuals tend to live between 10–15 years, while in captivity individuals may live up to 25 years.

Siberian Tiger Characteristics

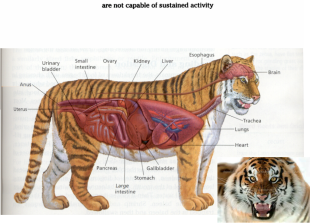

Siberia tigers have extended, supple bodies supported by somewhat short legs, with a fairly long tail. The skull of the Siberian tiger is large in size. The facial region is strong and very broad where the canine teeth are. Skull prominences are very high and strong in old males, and often much more massive than those found on the biggest skulls of Bengal tigers. The size variation in the skulls of nibe Siberian tiger individuals ranged from 33.1 to 38.3 centimeters (13.0 to 15.1 inches). Female skulls are smaller and not as heavily built and robust as those of males. The length of upper carnassial tooth over 2.6 centimeters (1.0 inch). Siberian tigers can jump horizontally as far as 25 feet. Vertically, they can jump over a basketball hoop. When asked how high a tiger can jump, one tiger biologist told John Vaillant, "As high as it needs to." [Source: Wikipedia]

Siberian tigers have exceptionally long canine teeth, measuring between 6.4 to 7.6 centimeters (2.5 to 3.0 inches) in length. The longest canines of any cat species, they are deeply anchored in the jawbone and are crucial for killing prey and eating meat. They are also equipped with pressure-sensing nerves that help the tiger identify the correct location to sever its prey's neck. [Source: Seaworld]

The difference between the Siberian tiger and the more common Bengal Tiger is that the coat of the Siberian tiger is much thicker. This helps it survive the frigid Siberian winters. Siberian tigers also have more white in the patterns on their head and on their underbelly. Their orange color is less bright than other tiger species. The color of Siberian tigers' fur is often very pale, especially in winter coat, but there can be great variations between individuals. The fur is moderately thick, coarse and sparse compared to that of other felids. The summer coat is coarse, while the winter coat is denser, longer, softer, and silkier. The winter fur often appears quite shaggy on the trunk and is markedly longer on the head, almost covering the ears. Because of the winter fur's greater length, the stripes appear broader with less defined outlines. The whiskers and hair on the back of the head and the top of the neck are also greatly elongated.

Russian tiger experts Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov wrote: “ An adult male can weigh from 320-350 kilograms (705- 770 pounds) and can reach almost three 3 meters (9.8 feet) in length. In strength, it is unrivaled in the Russian Far East. There is a story of a tiger that killed a healthy mare and drug it almost a kilometer. In this case, the tiger was later shot and found to weigh a mere 140 kilograms (309 pounds.). Few tigers die from old age. Crafty traps and bullets, sickness, and fights with brown bears tend to cut short the lives of both young and adult tigers. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

“One should note that a tiger’s vision is not among its better qualities. Even at a short distance, a tiger mistake you for a stump. It might move up close to leave its mark on what it thinks to be merely a conspicuous log. However, if the stump, dumbstruck with fear, suddenly gives some sign of life, the animal will pick up on this right away. It has a keen ability to distinguish moving objects. The tiger is not afraid of deep snow and biting frosts. The animal has an excellent coat and extremely broad paws. With a sure-footed leap, a tiger can more easily rush up to its prey in deep snow. Nevertheless, heavy snow is a hindrance since it reduces the number of ungulates, decreasing by death and migration the tiger’s already limited amount of prey.”~~

Places Where the Siberian Tigers Live

Siberian tigers today are confined primarily to the Ussuri Taiga, a forest different from the normal Russian taiga. Located between the Ussuri and Amur Rivers in the Far East and dominated by the Sikhot Alim Mountains, it is a monsoon forest filled with plants and animals found nowhere else in Siberia or Russia and instead are similar to those found in China, Korea and even the Himalayas. In the forest there is s lush undergrowth, with lianas and ferns. Wildlife include Siberian tigers, Asian black bears, Amur leopards and even tree frogs. The Siberian Tiger Project is located here. The 1970 Akira Kurosawa film “Dersu Uzala”, about a Tungus trapper, was set here.

Sikhot Alin Reserve and Kedrovaya Pad Reserve within the Ussuri Taiga are the last homes of the Siberian tiger. The largest wildlife sanctuaries in the Far East, they embrace 1,350 square miles of forested mountains, coastline and clear rivers. Other animals found in Sikhot Alin reserve and Kedrovaya Pad reserve include brown bears, Amur leopard (of which only 20 to 30 remain), the Manchurian deer, roe deer, goral (a rare mountain goat), Asian black bears, salmon, lynx, wolf and squirrels with tassels on their ears, azure winged magpies and the emerald-colored papilio bianor maackii butterfly. Over 350 different species of bird have been sen here.

Dunishenko and Kulikov wrote: “In the 19th century, aside from the Sikhote-Alin and Malyi Khingan portions of Russia, tigers were found in southeastern Transcaucasia, in the Balkhash basin, in Iran, China and Korea. Now the Amur tiger is found only in Russia’s Primorskii and southern Khabarovskii Krais. This is all that remains of an enormous tiger population that formerly numbered in the thousands and that lived mostly in China. In the spring of 1998, one of the authors of this booklet took part in an international scientific study investigating the best tiger habitat remaining in the Chinese province of Jilin. We found three to five tigers there, mostly along the Russian border. Our general impression is that there are no more than twenty or thirty Amur tigers in all of China. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

The general area where Siberian tigers lives is called the Primorskii or Primorye, a region of the southeast Russian Far East that embraces Vladivistok. John Vaillant wrote in “The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival”: “Primorye, which is also known as the Maritime Territory, is about the size of Washington state. Tucked into the southeast corner of Russia by the Sea of Japan, it is a thickly forested and mountainous region that combines the backwoods claustrophobia of Appalachia with the frontier roughness of the Yukon. Industry here is of the crudest kind: logging, mining, fishing, and hunting, all of which are complicated by poor wages, corrupt officials, thriving black markets — and some of the world's largest cats.” [Source: John Vaillant. “The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival” (Knopf, 2010)]

Biodiversity of the Ussuriskii Taiga Forest

Siberian tigers inhabits the Ussuriskii taiga forest, a coniferous broadleaf forest that specifically favors the so-called Manchurian forest type. The Manchurian forests are located in riparian areas and are particularly high in biodiversity. John Goodrich of NPR wrote: “The most bio-diverse region in all of Russia lies on a chunk of land sandwiched between China and the Pacific Ocean. There, in Russia's Far East, subarctic animals — such as caribou and wolves — mingle with tigers and other species of the subtropics. It was very nearly a perfect habitat for the tigers — until humans showed up. The tigers that populate this region are commonly referred to as Siberian tigers, but they are more accurately known as the Amur tiger. "Imagine a creature that has the agility and appetite of the cat and the mass of an industrial refrigerator," Vaillant tells NPR's Linda Wertheimer. "The Amur tiger can weigh over 500 pounds and can be more than 10 feet long nose to tail." [Source: John Goodrich, NPR, September 14, 2010]

Dunishenko and Kulikov wrote: "The range of biodiversity experienced by the early explorers in the Ussuriskii taiga forest is hard to imagine. Read Vladimir Arsenev and Nikolai Przhevalskii and you’ll realize that the region’s present-day richness is but a sad remnant of what was once found here. The fact is, that not all that long ago there was a lot more to be found in our taiga. Old-timers can still vividly recall the herds of deer, numbering in the hundreds, that migrated the lightly snow covered regions of China, the incessant moan in the taiga when red Manchurian deer were mating, the endless waves of birds, the rivers boiling with salmon. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

"And my lord, how many wild boar there used to be in the taiga! All winter long, the southern exposures of oak-covered hills were dug up by droves of wild pigs. Snow under the crowns of Korean pine forests was trampled to ground level as wild boar gathered pine cones throughout the winter. A symphony of squeal and moan! Mud caked wild boar racing around the taiga, rattling around in coats of frozen icycles after taking mud baths to cool passion-heated bodies. Horrible, blood caked wounds, chattering tusks, snorting, bear-like grunting, squawky squeaking, oh the life of a piglet.~~

"This was an earlier image of the Ussuriskii taiga. Just 30 years ago a professional hunter could take 60 to 80 wild boar in a season! There was more than enough game for the tiger out there among the riotous forest “swine.” Tigers strolled lazily, baron-like and important. They avoided the thick forests: why waste energy with all the boar trails around — you could roll along them sideways! It was only later on that the tigers took to following human trails.~~

"How many tigers there used to be in the wild can only be conjectured. Southern Khabarovskii Krai is a natural edge of their habitat; at one point in history there was a substantial tiger population that spilled over into surrounding regions. The tiger’s range coincided, for the most part, with Korean pine and wild boar distribution, and the number of tigers in the Russian Far East in the last century was at least one thousand. Tigers densely settled the Malyi Khingan and the Korean pine, broad leaf deciduous forests typical of southern Amurskaya Oblast. Lone animals wandered out as far as Lake Baikal and Yakutiya."~~

History of the Siberian Tiger in Southeast Russia

Sergei Stroganov wrote in his book “The Wild Animals of Siberia. Predators” (1962): “A series of authors have written about the appearance of tigers at the limits of eastern Siberia. Nikolai Severtsov (1855) recalls that a tiger was caught in 1828 in the Balagansk region (on the Angara River, 52 degrees 30 minutes north). Gustav Radde reports a tiger being seen in the Trasnsbaikal region (1862). According to Radde, this tiger was killed in 1844 near a factory in Nerchinsk. Rikard Maak (1859), as well as other travelers, writes that tigers were seen on the Argin and in Transbaikal, in the mountains of the Stanovyi range and even in Yakutiya. A stuffed tiger killed in November 1905 on the Aldan River, about 80 kilometers (50 miles) below Ust-Mai, is housed in a Yakutsk museum. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

“Tracks of a second tiger were observed in the same region. According to a report in the January 14, 1945 edition of the newspaper “Konsomolskaya Pravda,” two tigers were bagged in Chitinskaya Oblast in the same year. We suspect that the tigers seen in Chitinskaya and Irkutskaya Oblasts came in from China, while those in Yakutiya came from Priamure. However it happened that tigers appeared in those regions, even this modest bit of data from the scientific community of the time confirms that the population of this now rare predator was large and thriving.~~

“The tiger has always been hunted. The animal was practically outside the law and by the 1930s, fewer than thirty individuals of the Amur subspecies were left in the wild. World War II saved the tiger from total annihilation. People went to fight in that war and most of them never returned. For a while, few humans were in the taiga. Then the borders were closed down and the one time lively trade in contraband bones and skins ground to a halt. A total ban on hunting was put in place in 1947. According to the data of Lev Kaplanov who studied tiger distribution in the 1940’s, during the times of his research, there were no tigers left in the Bikin and Khor river watersheds and in the entire Russian Far East there were less than 20-30 individuals. Later, in 1952-55, the famous naturalists Vsevolod Sysoev and Gordei Bromlei pointed out that in Khabarovskii Krai, the tiger was population was limited to the Mukhen, Nelma and Sutary river basins.~~

“Relatively regular census data have been gathered since 1957. The earliest of these recorded at least 23 tigers in Khabarovskii Krai: eight in the Bidzhan River watershed in the Jewish Autonomous Region, 12 in Imeni Lazo Raion and one each in Vyazemskii, Nanaiskii and Komsomolskii Raions. Bromlei’s data for Primore — 35 tigers — brings the total to 60 individuals. The situation in China at that time is at best a guess. But it is clear that intensive hunting and forest harvesting and habitat conversion continued in China and that by the 1960s, all that remained were isolated, small pockets of tigers. Census data for Khabarovskii Krai indicates tiger numbers for certain years: 1970 - 20; 1978 - 34; 1985 - 68-69; 1986 - 91; 1993 - 54-56; 1994 - 57-58." ~~

American conservationist Dale Miquelle believes that there were as few as 20 Amur tigers left in the Far East. But communism, which had been ruinous for many Russian people, was actually good for Russia’s big cats. During the Soviet era, the borders were tightened, and it became difficult for poachers to get the animals into China, the primary market for tiger pelts and parts. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the borders opened again, and perhaps more calamitously, inflation set in. “You had families whose entire savings was now worth zilch,” said Miquelle, whose wife, Marina, is a native of Primorsky. “People had to rely on their resources, and here, tigers were one of the resources. There was a massive spike in tiger poaching.” In the mid-1990s, it seemed possible that the Amur tiger would soon be extinct. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 */]

Siberian Tigers in Khabarovskii Krai

Dunishenko and Kulikov wrote: "Khabarovskii Krai covers 78 million hectares (192 million acres). Tigers now live on 3.3 million hectares (8.1 million acres) of which only two million hectares (4.9 million acres) is typical tiger habitat. Prime habitat is Korean pine, broadleaf deciduous forests, Korean pine and spruce forests, and Korean pine and broad leaf deciduous forests that cover portions of Bikinskii, Vyazemskii, Imeni Lazo and Nanaiskii Raions. Lone tigers are encountered in Komsomolskii, Sovgavanskii, and Vaninskoi Raions. That’s the full extent of the tiger’s home in Khabarovskii Krai. In truth, the latter three Raions are no longer the tiger’s primary habitat, just its outer range. The same can be said for Khabarovskii Raion, where there is very little habitat that is suitable for tigers. [Source: “The Amur Tiger” by Yury Dunishenko and Alexander Kulikov, The Wildlife Foundation, 1999 ~~]

The sighting "of two tigers in the Khekhtsir was a big sensation, as it marked the tiger’s first appearance here since 1937. But in reality, it is already too late for tigers to return to the Khekhtsir for good. The creeping of the suburbs from the large city has brought too many people here, and conflict with the tigers is inevitable.~~

"Tigers are no longer encountered on the left bank of the Amur River. The last tiger tracks on the Minor Khingan were spotted in 1975. And the situation in the Sikhote-Alin is not much better. The foothills and the lower areas of the mountains are slowly, but irreversibly, being transformed by humans, and higher up there is nowhere to spend the winter. The snow pack is heavier and there is less prey. A heavy snow pack will shrink tiger habitat dramatically and will crowd the animals into the areas with less snow. But these areas overlap with heavily populated foothills. The result is panic! And how is there panic! There what panic there is! Tiger tracks seem to be everywhere! Although, in reality, there no more tracks than there used to be.~~

" In 1996, there were between 64 and 71 tigers in Khabarovskii Krai. Is that a lot or a few? We believe, given the situation at hand, that this question is a little out of place. People might say that there are “a lot” of tigers only because they happen to think there is insufficient game for the hunters. But then the real solution is to reduce the amount of poaching of tiger prey, not the number of tigers. There is also a need to reduce the number of wolves, brown bear, lynx and wolverines, since in the foreseeable future, these animals are not endangered. As for the tiger, in the 1980’s it might have made sense to hold the numbers to between 40 and 50, but it is definitely too late to do that now. At least twelve adults were lost annually in the early 1990s and still today we are losing no fewer than eight to ten annually. All this when the total population is around fifty.~~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025