FURS AND RUSSIA

For many years Russia produced about a 40 percent of the world's fur. That figure has declined. St. Petersburg used to have the largest fur action in the world and the Soviet Union was the main global supplier of mink, sable and fox. Most of the furs were sold abroad and fur was an important source of hard currency. Although the Soviet Union produced huge volumes of fur and fur hats were common enough but a fur coat was something that Russians could dream about and only foreigners could afford.

Sable is the most prized fur. Pelts from wild animals are regarded as more valuable than farm-raised ones. Mink fur is more common and minks—as well as foxes—are easier to raise in fur farms than sable. Kinds of fox that are used to make fur garments include the blue fox and white fox from the Arctic region, and the platinum and silver fox from North America, Asia and Europe.

St. Petersburg still has the biggest fur auction in Russia, with a large selection of sable, mink, fox and squirrel furs. The auction is held in English in a Soviet-style amphitheater built in the 1930s. There are bigger auctions in Helsinki, Copenhagen and Toronto but St. Petersburg is regarded as the best place to get quality furs at a good price.

Animal Rights and the Russian Love of Fur

Russians have traditionally loved furs. Fur is prized for both its warmth and beauty. Fur hats for men and fur coats are fixtures of Russian life, helping them stray warm in the long winter months. The has never been a strong anti-fur movement in Russia. And there wasn’t one in the Soviet Union. Fur is not necessarily associated with rich. Many middle class people wear fur because it is regarded as the best way to stay warm in the harsh winter. For a while furs from Amur racing dogs were popular.

Animal rights groups have a relatively low profile in Russia and people can wear furs without fear of harassment. In one rare animal rights protest, an English women and a Russian woman walked through Red Square wearing nothing except a banner that said they would rather wear nothing than wear fur. According to press reports they attracted no noticeable supporters.

Explaining the view of many Russians about fur, a saleswoman at a fur store in St. Petersburg told AFP: “Fur is part of our tradition because of our climate. When you live in Moscow, you can do without it if you don’t have it, but when I was in the Ural mountains, I undersold that without a fur coat and fur boots, you can freeze to death, and there is nothing Greenpeace can do about it.”

Russian Fur Industry

The fur farm industry in Russia produces mostly minks and polar foxes. There are some for sables but the fur from these animals is regarded as much lower quality than that of wild sable. The carnivorous fur animals are fed meat supplied by meat plants. In the 1950s and 60s, they were often fed whale meat. Fur animals have traditionally been slaughtered in the middle of the winter when their coats are the thickest. In Soviet times, the fur association Soyuzpushnina monopolized every aspect of the industry but now buys and sells furs in competition with private traders.

Demand for fur coats declined significantly in Russia and around the world—with the exception of China—after the anti-fur and animal rights movements took hold. The decline in demand for furs caused the price of furs to drop so low the cost of feeding the animals exceeded the money that could be earned from selling the furs.

Patrick E. Tyler wrote in the New York Times: “Russia exports its pelts — as it does other natural resources, like timber, oil, gas and metals — because the economy perennially fails to attract the investment needed to add value to its products. Still, Russian fur is a $1 billion industry by official figures, and if smuggling, poaching and unofficial trade that skirts regulation and tax collection are counted, the estimate reaches $2.5 billion. [Source: Patrick E. Tyler, New York Times, December 27, 2000 ^]

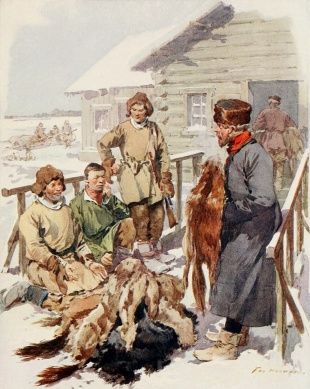

A significant portion of Russia’s furs come from hunters and trappers that range the wilderness trapping and shooting fox, sable, squirrel, mink, lynx and wolverine. Lynx, beaver, marten, fox and other animals have traditionally been caught with foot traps that often leave the animals writhing pain until they die of hunger or are clubbed by a hunter. In the Soviet era, fur hunters were paid by regional state farms. Many trappers complained about the money they received. One told National Geographic, "They pay us 1,200 rubles—about $6—for a sable that will sell for $150 in Irkutsk.”

Hunters and fur farmers sell their furs to traders or buyers: some of whom come to them, some of whom work out of trading posts and towns and cities near fur-producing areas. Fur farmers and fur traders have representative sold their furs at fur auctions. They are often paid in cash. The prices of furs fluctuates widely in accordance with supply and demand. Before furs are processed they are graded according to size, texture and general condition. Production of pelts raised in the U.S. increased by 6 percent to 3.76 million pelts in 2014. The average price per pelt, at $57.70 was up $1.40 from the prior year

Decline Russian Fur Industry

In 2000, only about 30 of the 200 fur farms in Russia were stiller operating. The others had either closed or were on in the process of closing. Many of the ones still operating were of poor quality. There were only five sable farms left,.

Patrick E. Tyler wrote in the New York Times:“Hundreds of thousands of caged mink, sables and fox have died as more than 100 fur farms, cut off from the state credits of the centrally planned economy, lost the means to pay salaries or buy the tons of meat and fish needed each day to feed the animals, many of which died of disease resulting from poor nutrition. [Source: Patrick E. Tyler, New York Times, December 27, 2000 ^]

''In the Soviet period we had the largest fur production in the world,'' Viktor Chipurnoi, vice director of Soyuzpushnina, told the New York Times, ''but now the largest producer is Denmark, followed by the United States, Holland and Finland.'' Russia has also lost much of its fur processing industry to China and Europe, and the design houses of Italy, France and the United States have taken over most of the high value-added aspects of fur production. ^

History of the Fur industry

Prehistoric man in Europe kept himself warm with a variety of animal of skins. There is evidence that these skins were sewn together around or 30,000 years ago or earlier. As early as 3500 B.C. there is evidence of fur as a symbol of wealth. The Pazyryk woman, a 2400-year-old frozen mummy discovered in southern Siberia on the Ukok Plateau near where Russia, Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan all come together, was found draped in a robe of marten fur.

The Viking opened up their river routes into present Russia beginning around A.D. 800 partly to buy, sell and trap fur-bearing animals. Cossack fur traders and hunters explored Siberia and the Far East in the 16th and 17th century in their search for fur sources, in the process opening up travel routes to these area that allowed Russia to claim the region and later Alaska. Cossacks collected imperial fur tributes from native groups and trapped their own animals.

Irkutsk has been a major trading center since tsarist times. Founded in 1661, it mainly funneled Siberian furs to the aristocracy in the east. Many people got rich as the fancy stone and brick houses of fur traders, gold magnates and merchants, that are still around, testify. In the 17th century, two belts of black fox could be traded for 50 acres of land, a cabin, five horses, 10 head of cattle, 20 sheep and dozens of chickens.

The 1990s and the early 2000s was a bad time for fur sales as animal rights made wearing furs something to be ashamed of. The fur industry of Russia was no longer subsidized as it was in the Soviet era and two thirds of all the farms that raised fur animals closed down. For a while sable was virtually unavailable on the world market. By the mid 2000s, the fur market was picking up again thanks mainly to rising incomes and demand in Russia and China. Sable furs were fetching $300 a piece. At the St. Petersburg auction in 2004, 530,000 furs were sold for $14 million. This was not nearly as high at in Soviet times but was better than recent years. Nouveau riche Russians were able to pay $2,000 or $3,000 for a fur coat, many of them on credit.

Fur Farms

Fur farms raise mink and fox, and to a lesser extent sable ermine and lynx. Fur farming was developed in the 1920s when it was learned how to breed fur-bearing animals in captivity. Minks, fox and chinchillas it was learned are much easier to raise than sables. Many farms were in Siberia around Irkutsk, which contained the largest fur warehouse in the world. It handled millions of mink, fox and squirrel pelts a year and up to 160,000 sable pelts, from both farms and trappers. In the Russian Far East minks and sables at fur farms were fed whale blubber.

Eighty-five percent of the fur industry’s skins come from animals living captive in fur factory farms. These farms can hold thousands of animals, and their farming practices are remarkably uniform around the globe. The most commonly farmed fur-bearing animals are minks, followed by foxes. Chinchillas, lynxes, and even hamsters are also farmed for their fur. Fifty-eight percent of mink farms are in Europe, 10 percent are in North America, and the rest are dispersed throughout the world, in countries such as Argentina, China, and Russia. [Source: People for the Ethical Treatment (PETA)]

Throughout their history, mink farmers have employed selective breeding to develop a wide variety of pelt colors, many of them either rare or unknown in nature. These include white, plus a host of shades of brown and gray, sometimes with tinges of blue or pink, and bearing such exotic names as lavendar hope, sapphire, gun metal and mahogany. [Source: Fur Commission USA]

Mink typically breed in March, and give birth to their litters of young, or “kits”, in May. These litters may range from three to 13, but four to five is average. The kits are weaned at six to eight weeks of age. Farmers vaccinate their kits for botulism, distemper, enteritis, and, if needed, pneumonia. The animals molt in the late summer and early fall, after which they produce their winter fur. They are then harvested in their prime in late November and December.

Fur Farms According to Fur Industry

According to the Fur Commission USA: “Today’s farm-raised furbearers are among the world’s best cared-for livestock.Good nutrition, comfortable housing and prompt veterinary care have resulted in livestock very well suited to the farm environment. Most American fur farms are family businesses, often operated by two or three generations of the same family. A young farmer will typically take time out to gain a college or university degree in agriculture, biology or business, and then begin participating in the management of the family farm, eventually either taking over or leaving to start his or her own operation. This new operation, however, may still be under the umbrella of the family farm, with the result that one fur farm may actually comprise two or more operations next door to each other. In addition to mink and fox farming, there are many other types of fur farmed in North America, such as chinchilla, rabbit, bobcat, lynx and finnraccoon. [Source: Fur Commission USA (FCUSA) ^^]

“In the wild, most young mink don’t survive through the first year. In contrast, a farmer’s care ensures that almost all domesticated mink live until the end of the year, when they are harvested. The best of the herd are selected for breeding in the following spring, ensuring that the farmer’s stock keeps improving. Providing animals with humane care is an ethical obligation of all livestock farmers, while for mink farmers it also makes good business sense, since the healthiest animals produce the finest pelts. ^^

“As with all America’s livestock producers, fur farmers are regulated by state departments of agriculture. Farmers are responsible for their animals’ care from birth to death. While standards of animal care and farm management are developed over years of work by experts, including farmers and veterinarians, when it comes to euthanasia, farmers adhere strictly to recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association. In accordance with the recommendations of the AVMA, the only method of euthanasia approved for mink by FCUSA is controlled atmosphere euthanasia using bottled gas, either pure carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide. ^^

“When harvest time comes around, a mobile unit is brought to the animals’ cages to eliminate stress that might be caused by transporting them long distances. This mobile unit includes a specially designed airtight container which has been prefilled with cool gas. The animals are placed inside and immediately rendered unconscious, dying quickly and humanely.” ^^

Fur Farms According to PETA

According to the animal rights group PETA: “As with other intensive-confinement animal farms, the methods used in fur factory farms are designed to maximize profits, always at the expense of the animals. Mink farmers usually breed female minks once a year. There are about three or four surviving kittens in each litter, and they are killed when they are about 6 months old, depending on what country they are in, after the first hard freeze. Minks used for breeding are kept for four to five years. The animals—who are housed in unbearably small cages—live with fear, stress, disease, parasites, and other physical and psychological hardships, all for the sake of an unnecessary global industry that makes billions of dollars annually. [Source: People for the Ethical Treatment (PETA) ]

“To cut costs, fur farmers pack animals into small cages, preventing them from taking more than a few steps back and forth. This crowding and confinement is especially distressing to minks—solitary animals who may occupy up to 2,500 acres of wetland habitat in the wild. The anguish and frustration of life in a cage leads minks to self-mutilate—biting at their skin, tails, and feet—and frantically pace and circle endlessly. Zoologists at Oxford University who studied captive minks found that despite generations of being bred for fur, minks have not been domesticated and suffer greatly in captivity, especially if they are not given the opportunity to swim. Foxes, raccoons, and other animals suffer just as much and have been found to cannibalize their cagemates in response to their crowded confinement. Animals in fur factory farms are fed meat byproducts considered unfit for human consumption. Water is provided by a nipple system, which often freezes in the winter or might fail because of human error.

“No federal humane slaughter law protects animals in fur factory farms, and killing methods are gruesome. Because fur farmers care only about preserving the quality of the fur, they use slaughter methods that keep the pelts intact but that can result in extreme suffering for the animals. Small animals may be crammed into boxes and poisoned with hot, unfiltered engine exhaust from a truck. Engine exhaust is not always lethal, and some animals wake up while they are being skinned. Larger animals have clamps attached to or rods forced into their mouths and rods are forced into their anuses, and they are painfully electrocuted. Other animals are poisoned with strychnine, which suffocates them by paralyzing their muscles with painful, rigid cramps. Gassing, decompression chambers, and neck-breaking are other common slaughter methods on fur factory farms.

“Fur farmers use the cheapest killing methods available, including suffocation, electrocution, poisoning, and gassing.” At one farm video by PETA “the farmer grabs the minks by their sensitive tails and shoves them into a crude wooden “kill box” to be gassed with carbon monoxide. One mink in the video— like many animals killed for their fur— doesn’t die immediately. After admitting, “I see chests moving,” the farmer then tries to break the mink’s neck by slamming the animal against the side of the gas chamber. The farmer in this video casually describes ripping the bloody pelts off minks’ bodies, snapping the animals’ penis bones and using old pruning shears to cut off their paws.

“The fur industry refuses to condemn even blatantly cruel killing methods such as electrocution. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, electrocution causes “death by cardiac fibrillation, which causes cerebral hypoxia,” but warns that “animals do not lose consciousness for 10 to 30 seconds or more after onset of cardiac fibrillation.” In other words, the animals are forced to suffer from a heart attack while they are still conscious.”

Fur Processing

The first step in the fur processing process is "dressing" the pelt, the scraping of skin to remove any undesirable matter and stop decomposition. Next is washing and tanning the pelt with a variety of chemicals that can range from salty acid and various minerals to formaldehyde. After soaking, pelts are dried and placed in a revolving drum. Then they are cleaned and sometimes placed in sawdust to remove the oils. The fur is then placed in wire baskets which are spun to remove the sawdust. The fur is then combed and fluffed.

To improve a fur's appearance, manufacturers use a number of techniques: 1) dying with chemicals, often done to change a variegated fur into a uniform hue; 2) unhairing, removal of the guard or top hairs, leaving behind only the body hairs; 3) pointing, the gluing of hair of another animal such as a badger to cover bare sports in the fur; 4) blending, a process in which stripes and the color of underfur are emphasized by brushing in certain chemicals by hand; or 5) shearing, cutting away inferior skin or other defects. Other techniques are used to straighten or curl the hair.

Furs are dyed in a number of different ways. Some are dipped in vats of dye and then brushed with paste. Others are brushed with paste and beaten with rattan to get the paste out. White furs are often bleached because they are rarely uniformly pure.

Making a Fur Coat

Paper patterns drawn to life-size scale by a designer are given to the cutter, which selects the skins by color, texture, size and uniformity and matches them to the pattern. Some skins are best suited for the collar. Others are better suited for the sleeves or body.

Once the matching is completed the cutter slashes the skins into stripes of certain widths and these are sewn together by a machine operator. Once sections such of sleeves have been cut and sewed together they are given to a workers called a mailer.

The mailer takes a pine board and a piece of chalk. With the chalk he outlines the pattern on of the sections on the board. He then spreads the section along the chalk outline s and nails them down. Afterwards the boards are set aside to allow the skins to dry slowly and evenly. Finally the various parts are taped along the edges and sewn together to make a fur coat. Then lines and buttons are added. The last process is glazing, which gives the fur a fluffy and glossy appearance.

Fur Coats in China

In a country wear people eat dogs and take tiger bone medicines, wearing a fur coat is not looked upon with kind of disgust that it in the West. Harbin-based Northeast Tiger Fur is one of the world’s largest fur companies.

Chaowal Street is a dusty market alley in Beijing, featuring more than 100 stalls selling nothing but fur garments: coats, jackets, hats, gloves and other items made from mink, rabbit, goat, fox and even dog. The most serious buyers are Russians. Almost one out of three coats ends up in former Soviet Union.

One Lithuanian buyer on Chaowal Street told the Washington Post he visited Beijing every three weeks and said he purchased thousands of coats. A Russian trader said, "The quality is not very good. But its cheap, and it stand up better than our fabrics.”

When told about animal rights campaigns against fur coat sellers in the West, one Chinese trader on Chaowal Street told the Washington Post, "We've heard that. But these animals are raised for their fur. Americans eat beef don't they? You kill those big animals for food: we kill those little minks for fur. What's the difference?"

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated June 2025