GIANT SQUIDS AND JAPANS

first photos of a living giant squid In December 2006, Tsunemi Kubodera, a scientist at the National Science Museum of Japan, caught a giant squid at depth of 650 meters about 27 kilometers off the northeast coast of Ototojima island in the Ogasawara Islands. The squid was not fully grown. It measured 3.5 meters despite having its two longest tentacles severed. It is estimated that if the tentacles were intact the squid would have measured seven meters in length.

In September 2005, the British magazine Nature reported that first video of a giant squid. The image of an eight-meter squid were taken as it tried to snag some bait at the end of fishing line at a depth of 900 meters on the North Pacific near Chichijima Island, 100 kilometers south of Tokyo, by a team led by Kubodera. The squid got snagged on a hook and wriggled free after a four-hour struggle but not before losing a tentacle that was retrieved by the scientists. The scientists were also impressed by the way the squid seemed to aggressively pursue its prey rather than waiting for it to pass its way.

Giant squids are one of the world's largest and most mysterious animals, giving rise to legends of sea monsters, like the kraken of Norway, stories of sailors being pulled into the sea, ships being overturned, and elementary school maps with fierce sperm whale and giant squid battles. The largest of all invertebrates, the giant squid can reach 60 feet in length (twice the length of a bus) and weigh up to half a ton. Generally living at depths of around 1000 meters, they have eight short tentacles like other squids as well as a 1½-foot-wide, parrot-like mouth, two long tentacles with sucker-cover clubs and the largest eye of any animal in history — at 15¾ inches it is the size of a human head. No one is sure how long giant squids live and nobody knows for sure what depths they live at. They are believed to catch prey by simply unfurling their arms and gathering in prey that passes their way. Its scientific name Architeuthis means “ruling squid.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

GIANT SQUIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, STORIES, VIDEOS factsanddetails.com

THE SEA AND JAPAN: CORAL, CURRENTS AND KELP factsanddetails.com

SEA LIFE IN JAPAN: DEEP SEA, GIANT AND BIOLUMINESCENT CREATURES factsanddetails.com

SHARKS IN JAPAN: SPECIES, FISHING, ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

SEA MAMMALS IN JAPAN: WHALES, SEALS AND THE DANGEROUS, HORNY DOLPHINS factsanddetails.com

First Videos of Living Giant Squids

The first recording of a living giant squid was made in 2006, by Japanese researchers in waters off Japan’s Ogasawara Islands. They managed to hook a specimen using bait and reel it to the surface where it was videoed. The first giant squid to be filmed in its natural habitat was filmed in 2012 by a remote operated vehicles (ROV) named the Medusa. It was was deployed in Japanese waters near where the 2006 encounter took place. Medusa’s camera system was able to operate in the darkness of the deep sea. This was an an important innovation over previous submersibles and ROVs, which usually relied on bright white light to navigate through the blackness of the deep sea. It is believed that such light scared away many creatures used to living in total darkness. [Source: Smithsonian]

In December 2006, Tsunemi Kubodera, a scientist at the National Science Museum of Japan, caught a giant squid at depth of 650 meters about 27 kilometers off the northeast coast of Ototojima island in the Ogasawara Islands. The squid was not fully grown. It measured 3.5 meters despite having its two longest tentacles severed. It is estimated that if the tentacles were intact the squid would have measured seven meters in length.

In September 2005, the British magazine Nature reported that first video of a giant squid. The image of an eight-meter squid were taken as it tried to snag some bait at the end of fishing line at a depth of 900 meters on the North Pacific near Chichijima Island, 100 kilometers south of Tokyo, by a team led by Kubodera. The squid got snagged on a hook and wriggled free after a four-hour struggle but not before losing a tentacle that was retrieved by the scientists. The scientists were also impressed by the way the squid seemed to aggressively pursue its prey rather than waiting for it to pass its way.

Giant Squids in Tokyo Bay and Giant Squid Sashimi

Giant squids periodically appear along Japan’s coast. One was sighted in March 2022. In March 2014, a giant squid weighing 24 kilograms (53 pounds) and 3.6 meters (11.8 feet) in length was caught in Tokyo Bay. Miura’s Keikyu Aburatsubo Marine Park Aquarium examined the giant squid after a local fisherman spotted it floating off Yokosuka, Kanagawa prefecture. It was captured alive by the fisherman but died several hours later. This is not the first time a giant squids captured in Tokyo Bay. In May 1968, a 6-meter giant squid had been found in Tokyo Bay off Miura in Kanagawa. [Source: Japan Daily Press, April 2, 2014]

In February 2015, a giant-squid tasting event was held in Imizu, Toyama Prefecture. One of the squid, which was 6.3 meters long and weighed 130 kilograms when it was landed in a fishing port in the city, is among the largest in the world ever captured. In the drying process, it shrank to 3.6 meters and six kilograms. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, February 22, 2015]

After the giant squid was brought ashore in Tottori in January 2014, The Daily Mirror reported: “Local residents were said to be working out just how many people the 220 lbs (100 kilos) squid could feed if cut into sashimi until they were told it contained too much ammonia in its body to be edible. The ammonia helps it stay buoyant.[Source: John Kelly, Daily Mirror, January 23, 2014]

Bunch of Giant Squids Caught Off Japan in January 2014

In January 2014, a giant squid caught by fishermen off coast of Tottori Prefecture in Japan. International Business Times reported: “Measuring 11 feet in length, the creature was hauled in from deep waters during a trawl for crabs and flatfish. “It was alive when the fishermen brought it on board the boat but died before reaching the coast. The squid’s length was drastically shortened by the absence of its two longest tentacles, which would have made its length around 8 meters (26 feet) had they been attached. [Source: Dominic Gover, ibtimes.co.uk, January 23, 2014]

Local expert Toshifumi Wada said it was significant the squid had been caught at a depth of around 244 meters 800 feet. The creatures usually live at depths of no less than 305 meters (1,000 feet). Wada told NTV: "This shows that the squid was swimming at that depth, so I think this is significant." AP reported there are plans for the squid to be preserved for research purposes.

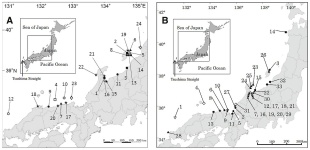

Also in January 2014, a fisherman in the Niigata Prefecture caught another giant squid and filmed its capture. Fisherman Shigenori Goto expressed regret afterwards about not treating the 360-pound lb creature with more respect. Another washed ashore near Kashiwazaki city and another two were caught in fishing nets. A giant squid was taken to the Himi fishing port in Toyama Prefecture on January 4, and another was discovered in a net off Sado Island in Niigata Prefecture on January 8 , according to The Japan Times. “Three squid were taken to Sado and Himi that measured between three and four meters long, the newspaper has reported. The two longest tentacles of one of the creatures caught in the town of Iwami in Tottori Prefechure were missing, meaning it could have spanned eight meters prior to its capture. [Source: Heather Saul, The Independent, February 20, 2014]

The Independent reported: “An increase in the number of giant squid being caught along the Sea of Japan coast is leading puzzled fishermen to fear their presence may be some kind of 'omen' - although experts think the invertebrate are simply a bit cold. Several of the creatures have been ensnared in fishing nets. A local fisherman who caught a four-meter giant squid off the coast of Sadogashima Island said, “"When I hauled up the net, the squid slowly came floating up," Shigenori Goto told local media at the time. "This is the first time I've seen such a large squid." He told The Japan Times yesterday: “I had seen no giant squid before in my 15-year fishing career. I wonder whether it may be some kind of omen.”

“Squid usually live 600 meters below the water’s surface where temperatures are 6 to 10 degrees, according to Tsunemi Kubodera,the collection director at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Squid can survive 200 meters below sea level as temperatures are around 7C in January. However, they fell to about 4 degrees in 2014. Mr Kubodera speculated that the giant squid have been rising closer to the surface looking for warmer water, but find themselves being swept closer to the shore and into the fisherman’s nets.

Giant Squids Observed by Divers off the Coast of Japan

In January 2023, a video of a giant squid swimming off the coast of Japan was posted on Viral Press. Fox News reported: Yosuke Tanaka, 41, encountered the 8-foot-long squid while diving with his wife Miki, 34, off the western coast of Japan. The couple, who operate a diving business in Toyooka city, found out about the squid from a fishing equipment vendor who spotted it in a bay, Japan Times reported. Tanaka and Miki took a boat out in search of the creature, staying near the shoreline as they scoured the bay. "I could see its tentacles moving. I thought it would be dangerous to be grabbed hard by them and taken off somewhere," Tanaka told the Times. "We didn’t see the kinds of agile movements that many fish and marine creatures normally show," he added. "Its tentacles and fins were moving very slowly." [Source: Peter Aitken, Fox News, January 20, 2023]

A researcher at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo told NHK news that the squid was likely around 1 or 2 years old, based on its size. The footage shows the giant squid floating near the surface, its tentacles drifting behind it while the couple swim nearby. The squid seems either unaware or undisturbed by their presence. The sheer size of the animal struck Tanaka, and he said he couldn’t help thinking about stories of squids fighting with whales. He assured that the experience would remain with him, saying it was "very exciting" and "there is nothing rarer than this."

In February 2014, a giant squid was captured alive — a rare event — in the Sea of Japan off Shinonsen, Hyogo Prefecture, but died shortly after being landed. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The squid measured 4.13 meters in length, but would have been eight to nine meters in length if its two longer tentacles had not been severed. It weighed between 150 and 200 kilograms. Fisherman Tetsuo Okamoto, 63, first caught sight of the squid as he was diving for turban shells about five kilometers from the town’s Moroyose fishing port at about 10:30am. The giant squid swam over his head when he was about eight meters below the surface. Okamoto managed to snare it with a rope, which he tied to his boat. He then transported the squid back to the port, but about 10 people were needed to haul it ashore. "I didn't think I'd ever get to see a giant squid swimming in the sea," he said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, February 27, 2014]

Firefly Squid

Firefly squid (Watasenia scintillans) are finger-size, bioluminescent squids. Averaging about 7.62 centimeters (3 inches) in length, they have special light producing organs called photophores that are found on many parts of their body, with large ones are usually found on the tips of their tentacles as well as around their eyes. These lights can be flashed in unison or alternated in patterns. This squid has arms with hooks and tentacles with hooks and one series of suckers. The mouth cavity has dark pigmentation. They live for about one year. [Source: Krupa Patel and Dorothy Pee, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Firefly squid have five lights around each eye and three each on the tips of two of their arms and even more covering their body. Joanna Klein wrote in the New York Times: “ “The firefly squid creates light via a chemical reaction inside its body, the same way a lightning bug does. The process involves wrangling together the dynamic duo of bioluminescence, two substances called luciferin and luciferase. Luciferin sits around waiting for luciferase, an enzyme that triggers luciferin to do what it does best — make light. “Up close, each squid looks like its own constellation of green and blue stars. Together, they form a bright blue nebula of bioluminescence, which is quite clear when the squid emerge from 1,200 feet during the spring to spawn. Firefly squid only live for a year. After making babies, they die. [Source: Joanna Klein, New York Times, April 26, 2016]

“Why the firefly squid glows is not precisely known. Theories range from attracting mates to deterring predators, but aren’t totally convincing. They also appear to lack the ability to regulate their flashes in synchronous patterns like some fireflies. Katsunori Teranishi, who studies the squid’s bioluminescence at Mie University in Japan, has found that the firefly squid constantly emits a weak light with no apparent advantage. But sometimes the light shines stronger, like a flashlight, from the squid’s arms. This might scare off nearby predators, but it could also attract those further away. ““The light cannot actively attract a mate, communicate with a mate, and deter a predator,” Dr. Teranishi said. When pressed for his own hypothesis for why the squid emits light, he suggested we ask the squids themselves.

Firefly squid live in the Western Pacific Ocean around Japan and are typically found at depths of 200 to 400 meters (656 to 1312 feet). They spend most of the day in deep water but swim up to the surface at night to capture prey. Firefly squid also rise up to the surface during their period of spawning, and gather in huge schools near the shoreline. One of the main known predators of firefly squid are Northern fur seals The squid’s photophores can be used against predators as a warning or as a form counter-illumination camouflage. /=\

Firefly squid is not protected under any conservation program. They have not been evaluated for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have have no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They feed on shrimp, crabs, fish, and planktonic crustaceans. The photophores on the tips of its tentacles are used in a flashing pattern to attract prey, especially fish. The photophores along the body and tentacles are also used to provide camouflage, frighten predators, and attract mates. Firefly squid sense communicate with vision and their photophores. They have highly developed eyes that contain three different types of light-sensitive cells and are believed to be capable of distinguishing different colors. /=\

Firefly Squid Behavior, Mating, and Development

Firefly squids are relatively deep sea squid, living at depths of 200-400 meters during the day, rising to the surface to feed at night and to spawn at certain times of the year. During the day they stay deep underwater. At night they come closer to the surface to feed. Compared with other species of cephalopod, firefly squid have complex visual systems with three different types of light-sensitive cells and the potential to discriminate light of different wavelengths (i.e. simple color vision). [Source: BBC]

Firefly squid are oviparous (young are hatched from eggs)and employ broadcast (group) spawning, the main mode of reproduction in the sea. It involves the release of both eggs and sperm into the water and contact between sperm and egg and fertilization occur externally. They engage in seasonal breeding and breed once a year, between April and June. On average females and males reach sexual maturity at age one year. [Source: Krupa Patel and Dorothy Pee, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Bioluminescent photophores are believed to play a role in attracting mates and are used for communication between squids. During spawning season firefly squids gather in large numbers near the surface and relatively near the shore to release their eggs. Once the eggs have been released into the water and fertilized, the adult squid die. There is no parental involvement in the raising of offspring. Adult firefly squid die after eggs have been released into and fertilized. This completes their one-year life cycle. /=\

Fertilized eggs hatch in in six to 14 days depending on the water temperature, which varies from six to 16 degrees Celsius. Higher temperatures produce faster hatching. According to Animal Diversity Web: At 15 degrees Celsius, one hour after fertilization, polar bodies appear, followed in five hours with first cleaveage. By 10 hours, 100 or more cells have been formed, and around 16 hours the embryonic lobe has been developed. The embryonic lobe covers about half of the egg in a day and a half. In four days, primordial eyes are present and oral depression starts. A day later, primordial arms, mantle, and funnel appear and then chromatophores appear on the mantle and the eyes are developed. Final organ and chromatophore formation and hatching occurs in 8-8.5 days. /=\

Harvesting, Watching and Eating Firefly Squid in Japan

Firefly squid are a popular season food in Japan, where they are eaten raw, known as Hotaruika in Japan, or cooked. Watch out though Eating raw firefly squid infected with spirurina type X larvae, belonging to the phylum Nematoda, can cause abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, creeping eruption, and ileus (bowel obstruction).

For a brief period in Toyama Bay on the west coast of Japan between the months of April and June billions of these squid rise up from their home in the depths to the surface to mate. Fishermen in the town along the bay sponsor excursions to the places where the squid are found. Normally polite and well behaved Japanese tourist push and shove their way on to the boat to make sure they get a good spot. When the boat reaches the squid site about one to two kilometers offshore fishermen haul in fixed nets. As the nets are lifted , the light emitted by the firefly squid causes the sea surface to erupt cobalt blue, evoking squeals of delight from the tourists. Japanese tourists sometimes dip nets into the water and pull up these living blue sparklers by the armful onto the decks of the boat, where every part of their body shrivels up except for their eyes which stick out grotesquely.

Joanna Klein wrote in the New York Times: “Hop on a fishing boat in Toyama Bay, Japan, in the wee hours of the morning and you may feel as if you’re in a spaceship, navigating through the stars as millions of firefly squid transform the water into a galactic landscape. All you need is a reservation to come aboard. “The best time to observe firefly squid is in April, in Toyama City, Namerikawa and Uozu City, said Osamu Inamura, director of the Uozu Aquarium in Uozu City (where you can find firefly squid in captivity). The boats depart from the Port of Namerikawa every morning at three a.m. from March 20 through May 8. You can catch the squid live at the only museum dedicated to them: Hotaruika Museum, also in Namerikawa. [Source: Joanna Klein, New York Times, April 26, 2016]

Firefly squid also draws large crowds to the shores of Toyama Bay during their spawning season. Large schools swim up to the shallow waters light up the dark water along the shore, giving tourists a nighttime show. This spectacle has led to the bay being named a Special Natural Monument and construction of a museum devoted to the species. /[Source: Krupa Patel and Dorothy Pee, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dancing Zombie Squids — a Japanese Delicacy

Janelle Lassalle wrote in the BBC: Katsu ika odori-don isn’t for the faint of heart. Loosely translated as ‘dancing squid bowl’, the controversial Japanese dish came to global attention in 2010 thanks to a YouTube video that went viral. The video depicts a headless squid perched on top of a bowl of noodles and roe. A mysterious hand appears with a teapot and pours what appears to be soy sauce onto the squid. The tentacles begin writhing wildly, granting the dish the unofficial title of ‘dancing zombie squid’. [Source Janelle Lassalle, BBC, February 1 2019]

As strange as the dish might seem, this is a contemporary take on a method of consumption in which seafood is eaten while still moving, referred to as odorigui (literally ‘dancing eating’), in Japan. Although the squid in this case is dead, its nerve cells are activated by the sodium in the soy sauce, which triggers the cells and commands them to fire, forcing the muscles to contract. And while odorigui can be found across Japan, the origin of this unique phenomenon is a little more mysterious.

The elusive practice of odorigui — which most often involves eating tiny, live fish — likely stems from fishing practices in port cities, with regional iterations on the practice. “In Shizuoka, a prefecture on central Honshu’s Pacific coast, it’s whitebait or shirasu that’s the preferred moving meal,” said Dave Lowry, a Japanese-restaurant critic and author of The Connoisseur's Guide to Sushi. “In Fukuoka, odorigui is almost synonymous with the shiro-uo, or ice goby, a tiny, eel-like fish that goes from the ocean to freshwater to spawn,” he added, explaining that the shiro-uo live in abundance around Fukuoka and are eaten alive because they start to deteriorate as soon as they die.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The mysterious case of Japan's ‘dancing zombie squid’” by Janelle Lassalle, BBC, 1 February 2019 bbc.com/travel

Image Sources: Youtube, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, Daily Yomiuri, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2025