WHALING IN JAPAN

Japan's old whaling ship Japan is one of the world's few whaling nations. According to CNN: Commercial whaling was banned in 1986 under a moratorium by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) after whale populations were almost driven to extinction by humans. Japan is one of three countries — along with Norway and Iceland — that continues to hunt whales, and officials argue that the industry is an important part of its culture and history — and also provides food security. Iceland, which has fiercely defended commercial whaling, said it would end whaling in 2024, citing falling demand for whale meat as well as “high operation costs and little proof of any economic advantage.” Commercial whaling continues in Norway, which experts say has quietly become the world’s leading whaling nation — killing more whales than Japan and Iceland combined. [Source: Heather Chen, Hanako Montgomery and Moeri Karasawa, CNN, June 3, 2024]

Japan has a quota this year of around 350 Bryde's, minke and sei whales, species which the Japanese government says are "abundant". The Bryde's and common minke are listed as being of "least concern" on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but globally the sei is "endangered". The Japanese government has argueed that eating whale is part of Japanese culture and an issue of "food security" in the resource-poor country which imports large amounts of animal meat. But consumption of whale has fallen to around 1,000 or 2,000 tonnes per year compared to around 200 times that in the 1960s. [Source: Simon Sturdee, AFP, May 23, 2024]

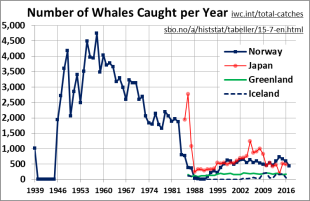

Whales have been prized in Japan for centuries as a source of both food and a variety of products. Japanese whalers caught 2,769 whales in 1986 the year before Japan ended commercial whaling in 1987, following the imposition of a worldwide ban on the hunting of endangered species of whales by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). At that time it announced that it would catch 875 whales for "research" purposes. The 2003 Japanese whale catch of 820 whales — mostly minke whales — represented about 42 percent of the world's whale catch. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEA MAMMALS IN JAPAN: WHALES, SEALS AND DANGEROUS, HORNEY DOLPHINS factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE WHALING INDUSTRY: SHIPS, PROCESSING, CREW factsanddetails.com

WHALE MEAT DISHES AND CONSUMPTION IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com ;

JAPANESE WHALING: SHIPS, CREWS, RESEARCH, NUMBERS AND CRITICISM OF IT factsanddetails.com ;

ANTI-WHALING AND JAPAN: SEA SHEPHERD AND THEIR ATTACKS ON JAPANESE WHALE SHIPS factsanddetails.com ;

JAPANESE GOVERNMENT SUPPORT OF WHALING AND AND WHY IT HAS ENDURED IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

DOLPHIN HUNTING IN JAPAN: TAIJI, THE COVE, DOLPHIN ACTIVISTS factsanddetails.com

Japan and the International Whaling Commission

Japan joined the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1951. The IWC was established in 1948 to manage whale resources and the whaling industry. Japan initially supported the IWC's policies, which were intended to promote sustainable whaling. In the late 1950s, Japan and other whaling countries considered leaving the IWC over harvesting quotas. [Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan]

In 1982, the IWC banned commercial whaling. Japan vigorously objected, calling for a phaseout of commercial whaling by 1987. However, since most of its trading partners, including the United States, supported the measure and threatened retaliatory measures if whaling continued, Japan finally agreed to comply with the ban. After that the Japanese used a a loophole in the IWC rules to carry out hunts in protected Antarctic waters for "scientific" research purposes. Those hunts were fiercely criticized, and the issue has been a diplomatic headache for Japan for years.

The IWC moratorium on commercial whaling went into effect in 1986. Although Japan stopped commercial hunts after 1986, it resumed taking whales for what it said was scientific research one year later. As a member of the International Whaling Commission, the Japanese government had long pledged that its fleets would restrict their catch to international quotas, but it attracted international wrath for its failure to sign an agreement placing a moratorium on catching sperm whales in the early 1990s and its insistence to carry out “scientific whaling.” The International Court of Justice ordered a halt to scientific whaling in 2014. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 15, 2024; Library of Congress]

Japan Withdraws from the IWC and Sets Its Own Riles for Whaling in Its Waters

In December 2018, Japan announced it was withdrawing from the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and would no longer comply with a decades-old ban on commercial whaling. Japan announced its withdrawal from the IWC in September 2018 and officially withdrew on June 30, 2019 and soon after began catching whales commercially once again, although its whaling activities are now restricted to the country's territorial waters in the North Pacific Ocean.

Under Japanese law, three species of whale are permitted to be hunted in its territorial waters and exclusive economic zones — endangered sei whales and threatened minke whales and Bryde’s whales, with endangered fin whales set to be added to kill lists. [Source: Heather Chen, Hanako Montgomery and Moeri Karasawa, CNN, June 3, 2024]

According to CNN: In 2018, it tried one last time to persuade the IWC to allow it to resume commercial whaling — and failed. So, it withdrew from the body and resumed commercial whaling months later, in defiance of international criticism.“Japan is no longer party to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and can argue that it is no longer bound by provisions and constraints,” Donald Rothwell, an international law professor at the Australian National University (ANU), told CNN. “Within its waters, it has the absolute authority to control the management of living resources — and that includes whales.”

Japan Resumes Commercial Whaling in 2019

In July 2019, Japanese vessels set sail to hunt whales commercially for the first time since 1987.Harumi Ozawa of AFP wrote: “The hunts are likely to spark criticism from environmentalists and anti-whaling countries, but are cause for celebration among whaling communities in Japan, which says the practice is a long-standing tradition. Japan decided last year to withdraw from the IWC after repeatedly failing to convince the body to allow it to resume full-scale commercial whaling. [Source: Harumi Ozawa, AFP, July 1, 2019]

”Whaling ships set sail on commercial hunts from several parts of Japan, including the town of Kushiro in northern Japan's Hokkaido. The group of five small vessels could be seen at the port there. Sunday. The boats have come from different parts of the country, including Taiji, an area known for dolphin hunts. Another flotilla of ships that once carried out whaling under the "scientific research" loophole will set out from Shimonoseki port in western Japan. "We are very excited at the resumption of commercial whaling," Yoshifumi Kai, head of the Japan Small-Type Whaling Association, told AFP ahead of the departure. "My heart is full of hope," he added.

After the whaling ships returned to port, Mari Yamaguchi of Associated Press reported: A Japanese whaling ship returned home after almost meeting its annual quota, ending its first commercial whaling season in 31 years. Operator Kyodo Senpaku Co. said its main factory ship Nisshin Maru returned to its home port of Shimonoseki after catching 223 whales during its three-month expedition off the Japanese coast. Nisshin Maru’s two support ships, Yushin Maru and No. 3 Yushin Maru, also returned to their home ports. [Source: Mari Yamaguchi, Associated Press, October 4, 2019]

“Kyodo Senpaku President Eiji Mori praised the whalers for returning with “better than expected” results despite earlier uncertainty because of their lack of experience in the area. “We were worried if we could catch any, but they did a great job,” Mori said. “We will examine the results closely and make a plan for the next season.” Of the quota of 232 whales allocated to the main fleet, they caught 187 Bryde's, 25 sei and 11 minke whales, only nine minke whales short of the cap. The fleet brought back an estimated 1,430 tons of frozen whale meat from the catch, down 670 tons from last year’s Antarctic hunts.

Separately, whalers operating smaller scale hunts in waters just off the Japan’s northeastern coasts were given a seasonal quota of 33 minke whales. Days after the resumption, their fleet of five small boats returned with two minke whales, whose fresh meat fetched as much as 15,000 yen ($140) per kilogram at a local fish market auction celebrating the first commercial hunt in three decades.”

Japan Says in 2024 It Will Hunt Fin Whales

In May 2024, Japan announced it had added fin whales, the world's second-biggest animal after the blue whale, to the list of species permitted in commercial whaling. Fin whales are listed as "vulnerable" by the IUCN. Hideki Tokoro, president of whaling company Kyodo Senpaku, said: "The government and the Institute of Cetacean Research have provided us with a quota that allows us to catch fin whales for 100 years. We can take the permitted number of whales without any concern at all. And in fact, there are a large number of fin whales, according to our crew's observations." Tokoro added, Whales "eat up marine creatures that should feed other fish. They also compete against humans. So we need to cull some whales and keep the balance of the ecosystem... It's our job, our mission, to protect the rich ocean for the future."

Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: On May 9, 2024 officials announced that Japan could start hunting fin whales soon. "Whales are important food resources and should be sustainably utilized, based on scientific evidence," Yoshimasa Hayashi, Japan's minister for foreign affairs, said at a news conference. Whether or not Japan goes ahead with its plans to hunt fin whales depends on the outcome of a public consultation of the country's newly drafted whaling policy — but it seems likely the changes will be approved, according to OceanCare. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 15, 2024]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists fin whales as vulnerable to extinction globally, although the species was still listed as endangered as recently as 2018 and is considered as such under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. However, there is insufficient data to pinpoint the status of local populations in the North Pacific, according to the IWC.

Without reliable population estimates, Japan's move to hunt fin whales is an "appalling step backward" for ocean protection, Clare Perry, a senior adviser at the Environmental Investigation Agency (an international NGO that investigates environmental crime and abuse), said in a statement. "Fin whales are one of Earth's great carbon capturers and should be fully protected, not least so that they can continue to fulfill their critical role in the marine environment," Perry said.

Scientific Whaling by Japan

Japan and Iceland have permission from the International Whaling Commission to kill whales for scientific research. Japanese scientists have argued they need to kill the whales — and dissecting their stomachs to determine what they eat, examine their skeletons and blubber for exposure to pollutants — to fully understand whales.

Japan began research whaling in the Antarctic Ocean in 1987 and in the northwest Pacific Ocean in 1994, both of which are "in line with the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling," according to the Fisheries Agency. A 1982 meeting of the IWC decided on a "temporary suspension" of commercial whaling, on condition the suspension would be reviewed by 1990. Research whaling is meant to study whales' ecological characteristics and their population in preparation for resuming commercial whaling. The plan to review the ban on commercial whaling by 1990 has been shelved due mainly to growing antiwhaling sentiment in many countries.

stomach of a minke whale The Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) is the body in charge of conducting whale research. It was set up in 1987 after the whale moratorium was established with $9.6 million in start up fund from Nihon Kyodo Hogei, Japan's largest whaling company.

Conservationist argue that thousands of scientist are studying whales without killing them and "scientific whaling" is “just commercial whaling in disguise.” The WWF has said that Japan could glean just as much information about whales using non-lethal biopsy darts ideal for checking DNA as they do by harpooning and killing whales.

Mark Brazil wrote in the Japan Times, “With the development of so many non-lethal research techniques — whether DNA sampling, satellite racking, telemetric tagging of analysis of feces to determine diet — the government supports for killing whales even for “research” seems as odd as killing giant pandas, Siberian tigers or Japanese cranes.”

Researchers keep the whale sex organs and ear parts for research. The meat, blubber and much of rest of the whale is sold commercially as a "byproduct" to fish markets. The oil is used to make cosmetics and perfumes. Much of the meat is sold as "whale bacon.” One whale researcher was sharply criticized for eating some of his research in home-made sashimi. The sale of whale products generates about $35 million a year. The cost of the "scientific whaling" is about $40 million. A $5 million subsidy makes up for the shortfall.

Japan is the only country engaged in scientific whaling although Iceland did some in the recent past. Any country can engage in the practice if it wants to. The IWC can review permits but not reject them. Most of the Japanese research whaling is done in the Antarctic. Some is done in the North Pacific.

Charade of Research Whaling

Jun Hoshiawa, executive director of Greenpeace Japan wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “For decades, Japan has exploited a loophole...and masqueraded its clearly commercial hunt as a “scientific research” operation. Over 10,000 whales have been killed to date, but only a handful of studies have been published...The industry, which relentlessly damages Japan’s international reputation, drains the public purse by about ¥1 billion every year.”

Douglas Chadwick, author several books on whales, wrote: “As for Japan, the flesh of minkes rendered for “research” all ends up in the country’s fish markets and restaurants which helps explain the nation’s lack of interest in nonlethal techniques that could provide the same biological data. Japanese officials insist that they need to cut open he stomachs to examine what whales are eating, even though DNA techniques now allow a thorough determination of a whale’s diet merely from small samples of the dung it leaves floating on the surface.”

Joji Morishita, an official with the Japan Fisheries Agency, wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Japan supports the regulated and controlled utilization of abundant whale species such as minke whales, while strongly supporting the protection of endangered species such as blue whales or right whales...Japan has no intention of being involved in the extinction of a whale species.”

In support of “scientific whaling” and sale of whale meat, Morishita wrote: “Hundreds of scientific papers have been submitted to the IWC Scientific Committee and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals as the fruit of our research. After research and data collection have been performed, the meat is released to the Japanese commercial market, in accordance with the requirement of the paragraph 2 of Article VIII which reads: “Any whales taken under these special permits (scientific whaling) shall so far as practically be processed.”... The whaling controversy is almost always about Japan and not a few people feel that Japan is unfairly singled out. We are also curious as to why hunting deer and kangaroos is considered OK, while hunting highly populated whale species is regarded as evil.”

Japanese whalers have said they want to hunt humpback whales in the Southern Ocean sanctuary to investigate if they are competing with minke whales for food. In response to that the Australian government has said it would send ship and spotter plane into the sanctuary to monitor what the Japanese whalers were doing.

Whale Catches by Japan

The Japanese have killed more than 10,000 large whales since starting its scientific whaling in 1987. They have killed about 600 to 700 whales a year in the early and mid 2000s, including the 440 minke whales it is allowed by the IWC to take from the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary in Antarctica "for scientific purposes." Norway takes about 460 minke whales a year.

Japan said it planned to catch around 200 whales in 2024. According to the IWC's most recently published whaling data, Japan took 25 sei whales, 187 Bryde's whales and 58 minke whales in 2022. In recent years, the country has also imported fin-whale meat from Iceland, according to OceanCare. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 15, 2024]

Despite a IWC vote that rejected Japan’s plan to expand its quota Japan decided unilaterally to double its 2000 quota. Japan planned ro kill 1,070 minke whales in Antarctica and the North Atlantic in 2006, 400 more than in 2005. In 2006, Japan also planned to hunt 10 fins whales in the Antarctic and total of 160 Bryde’s, sei and sperm whales in the Pacific.

Japanese whaling peaked in 2005-2006 when over 1,200 whales were caught. During the 2006-2007 whaling season in Antarctica, Japanese whaling ships returned early, with only half the catch they had expected to take. The hunt was dogged by criticism from Australia, New Zealand and other nations, harassment by anti-whaling vessels and a fire on one of the ships. The whale catch in the Antarctic Ocean in 2007-2008 was 551, all minke whales, well short of the target of 900 whales.

In 2007 Japan said it wanted to take 50 humpback whales to expand its “research” of whales but backed down after being sharply criticized by Australia. If Japan had gone through with the plan it would have been the first known large scale hunting of humpbacks since 1963. Japan has also announced plans to harvest sei whales. Japan had a quota of 1,300 whales in 2008-2009, including 850 in the Antarctic and 450 caught around Japan. Japan caught 680 whales (679 minke whales and 1 fin whale) in the Antarctic that year far short of its target of 850.

Japan killed 251 minke whales in the Antarctic in the 2013-14 season, 103 in 2012-2013 and 266 in 2011-2012, far below its target because of direct action by conservationist group Sea Shepherd. Japan’s Fisheries minister Yoshimasa Hayashi said in 2012-2013 the Japanese whaling fleet caught 103 minke whales and no fin whales, the lowest number since so-called research whaling began in 1987. Hayashi blamed the low number on the "unforgivable sabotage" by Sea Shepherd, with Japan’s Fisheries Agency saying the militant conservation group disrupted the hunt four times. [Source: AFP, April 5, 2013]

Japanese Whaling an International Relations

Japan has given the six small island countries in the Caribbean–St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Antigua, Dominica, Grenada and St.. Kitts and Nevis — over $100 million in aid between 1998 and 2006 essentially in return for their support on pro-whaling issues in the IWC. These countries began receiving the aid after voting in favor killing whales as members of the International Whaling Commission.

Japans has been accused by Greenpeace of "buying back the right to whale." One of Japan's whaling negotiators seemed to admit as much when he said, "To get appreciation of Japan's position, it is natural we must resort" to using overseas development adi and diplomatic persuasion.

Japan has encouraged countries like Palau, Cape Verde, Gabon, Nauru, Tuvalu and land-bound Mongolia to join the IWC to support their positions. In 2010 allegations were that Japan bribed small-nation members of the International Whaling Conference to vote for relaxed whaling rules with cash and prostitutes.. [Source: Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky, Daily Beast, February 5, 2014]

In retaliation for Japan's decision to kill 10 sperm whales and 50 Bryde's whales, the United States decided in 2000 to prohibit all Japanese boats from fishing in the 200-mile fishing zone of the United States. This prohibition wasn't a very harsh punishment considering Japan had not fished in these area since 1988.

The IWC has effectively become paralyzed by its division into anti-whaling and pro-whaling camps, with the two sides hardly even talking to one another. The Japanese claim the IWC had been "hijacked" by special interests NGOs such as Greenpeace and anti-whaling nations such as Australia and New Zealand. It has threatened to quit the IWC and form a new whaling body after facing strong opposition to its proposal to allow small-scale coastal whaling for four communities.

Australia and Japanese Whaling

The Australian government and Australian Prime Ministers often criticize Japan on the whaling issue. In December 2007, the Japanese government announced it was suspending its plan to hunt humpback whales. The move came at least partly in response to heavy pressure by from Australia, which threatened to follow Japanese whaling ships in the Antarctic and take legal action against Japanese whalers in international courts if Japanese whalers hunted the humpbacks. The assertive stance by Australia was the result of the new liberal-led government voted into power in November 2007.

In January 2008, the Australian government dispatched a vessel to follow the Japanese whaling fleet, monitor their activities and take photographs that could be used if legal action was taken against the whalers. Aircraft from Australia’s Antarctic division also monitored the whaling fleet.

The Australian government published photos of a mother minke whale and calf being processed by a Japanese whaling vessel. The photos were taken by an Australian customs vessel that was tracking the Japanese whaling fleet. The Japanese government complained. The New Zealand government has also sharply criticized Japanese whaling operations, calling them “deceptive” for operating under the guise of a scientific operation.

e UN court concluded Tokyo was carrying out a commercial hunt under a veneer of science. After the ruling, Japan said it would not hunt during this winter’s Antarctic mission, but has since expressed its intention to resume "research whaling" in 2015-16. In a new plan submitted to the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and its Scientific Committee, Tokyo set an annual target of 333 minke whales for future hunts, down from some 900 under the previous programme. It also defined the research period as 12 years from fiscal 2015 in response to the court’s criticism of the programme’s open-ended nature." Australia filed the case against Japan in May 2010 that resulted in the March 2013 by the the International Court of Justice -- the highest court of the United Nations -- that Tokyo was abusing a scientific exemption set out in the 1986 moratorium on whaling.

Image Sources: Japan Whaling Association, Institute of Cetacean Research

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025