JAPANESE ECONOMY IN THE EARLY 2000s

Beginning in February 1999, the Bank of Japan instituted a 0 percent short-term interest rate policy to ease the money supply, and in March the government poured 7.5 trillion yen in public funds into 15 major banks. As a result of these measures and growing demand for Japanese products in Asia, in late 1999 and 2000 signs of recovery were shown, such as increasing stock prices and revenue growth in some industries.

Beginning in February 1999, the Bank of Japan instituted a 0 percent short-term interest rate policy to ease the money supply, and in March the government poured 7.5 trillion yen in public funds into 15 major banks. As a result of these measures and growing demand for Japanese products in Asia, in late 1999 and 2000 signs of recovery were shown, such as increasing stock prices and revenue growth in some industries.

“In 2001, however, the economy slid back into recession because of domestic problems — sluggish domestic demand, deflation, and the continuing huge bad-debt burden carried by Japanese banks — as well as international factors that included a decline in Japanese exports due to deterioration of the U.S. economy. The unemployment rate, which had been only 2.1 percent in 1990, climbed up to 4.6 percent in 2011.

“The economy bottomed out at the beginning of 2002, entering a period of slow but steady recovery that has continued through the middle of the decade. After lingering for more than 10 years, the negative aftereffects of the bubble-economy collapse finally appear to have been largely overcome. The non-performing loan ratio of major banks fell from over 8 percent in 2002 to under 2 percent in 2006, and this has contributed to a recovery in bank lending capacity as banks are once again able to fully function as financial intermediaries.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MODERN HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ECONOMIC HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ECONOMIC HISTORY OF JAPAN FROM A.D 578 TO WORLD WAR II: THE WORLD'S OLDEST COMPANY, MEIJI PERIOD MODERNIZATION AND ZAIBATSU factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AFTER WORLD WAR II: HARDSHIPS, MACARTHUR, THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com; JAPAN'S POST-WORLD-WAR II ECONOMY AND THE ECONOMIC MIRACLE OF THE 1950s AND 60s factsanddetails.com; JAPAN INTHE 1950s, 60s AND 70s UNDER YOSHIDA, IKEDA, SATO AND TANAKA factsanddetails.com; JAPAN BECOMES AN ECONOMIC POWERHOUSE IN THE 1970s AND 80s factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN THE 1980s AND EARLY 1990s: NAKASONE AND THE PRIME MINISTERS THAT FOLLOWED HIM factsanddetails.com; MACROECONOMICS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPAN INC. AND REFORMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan JAPANESE BUBBLE ECONOMY IN THE 1980s AND ITS COLLAPSE IN THE 1990s factsanddetails.com; RECESSION, DEFLATION AND DECLINE FOLLOWING JAPAN'S BUBBLE ECONOMY COLLAPSE factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND ITS PRIME MINISTERS AND GOVERNMENT IN THE 1990s AND EARLY 2000s factsanddetails.com; JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI factsanddetails.com; JAPAN, THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS IN 2008 AND AFTERWARDS: HARD TIMES, STIMULUS AND SLIGHT RECOVERY factsanddetails.com; IMPACT OF THE MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI ON THE JAPANESE ECONOMY, FACTORIES AND COMPANIES factsanddetails.com; ECONOMY AFTER THE MARCH 2011 TSUNAMI: RECOVERY AND SLOWDOWN IN 2012 factsanddetails.com; JAPAN'S DECLINE factsanddetails.com ABENOMICS: SHINZO ABE’S POLICIES TO TURN THE JAPANESE ECONOMY AROUND factsanddetails.com; SUCCESSES OF ABENOMICS factsanddetails.com; ABENOMICS OBSTACLES AND FAILURES factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Slow Pace of Economic Reforms (2001) jpri.org/publications ; Japan’s Fake Economic Reforms in Foreign Policy Magazine(2010) foreignpolicy.com/articles ; Japan’s Phoenix Economy in Foreign Policy Magazine (2002) foreignaffairs.com ; Structural Reform in Japan: Breaking the Iron Triangle in Foreign Policy Magazine (2004) foreignaffairs.com ; Japanese Economic Recovery and the Future (2006) japansociety.org ;Google E-Book: Japan in the 21st Century, Environment, Economy and Society (2005) books.google.com/books

Good Websites and Sources on Economics: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry meti.go.jp/english ; Ministry of Finance of Japan mof.go.jp/english ; Japan Economy Watch japanjapan.blogspot.com ; Japan Center for Economic Research jcer.or.jp/eng ; Japan Inc. Economic and Business News japaninc.com ; Google E-Book: Japan in the 21st Century, Environment, Economy and Society (2005) books.google.com/books

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Koizumi Diplomacy: Japan's Kantei Approach to Foreign and Defense Affairs” by Tomohito Shinoda Amazon.com; “Japan's Dysfunctional Democracy: The Liberal Democratic Party and Structural Corruption” by Roger W. Bowen (2002) Amazon.com; “The Bubble Economy: Japan's Extraordinary Speculative Boom of the '80s And the Dramatic Bust of the '90s” by Christopher Wood Amazon.com; “Ashes to Awesome- Japan's 6,000-Day Economic Miracle” by Hiroshi Yoshikawa and Fred Uleman (2021) Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century” by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert P Bix Amazon.com; “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John Dowser of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1999. Amazon.com; “Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power” by Sheila A. Smith (2019) Amazon.com; “Japan in Transformation, 1945–2020 by Jeff Kingston Amazon.com

Need for Economic Reforms in the 2000s in Japan

Sizing up Japan's problems after the 1990s Recession, Tagart Murphy, a former banker and author of “The Weight of the Yen”, told Time: "Japan's problem is that the methods it used to run the economy since 1950 simply don't work now. Japan is not going to see growth until it overhauls the way the economy works."

A general theme of Japan's critics is that the cozy relations between Japan's large companies and the government no longer seems to work and Japan must open up its markets to make the Japanese economy more efficient, responsive and competitive.

Some Japanese companies have made adjustments and are leaner, meaner and more competitive than ever. Other have stuck with their old ways and stagnated. Weak companies need to be allowed to go bankrupt to clear away money-losing enterprises that drag down the economy. Efforts are being made to make the Japanese economy more reliant on domestic demand rather that exports. Smokestack industries like cement, chemicals and paper are merging and shrinking their work force. Cartels have come apart as a consequence of tough economic times, tougher antitrust laws, and aggressive foreign competitors taking advantage of yen fluctuations and openings in the markets.

Deregulation in Japan

Some Japanese economists blame Japan's economic problems on government intervention in the private economy which have suppressed market forces to boost industrial output. In an effort to make the Japanese economy more efficient, troublesome licensing procedures have been discarded. This has made it easier to form new businesses, for foreign companies to enter Japanese markets and for foreigners to buy Japanese companies. Despite the protest of Japanese farmers, the Japanese government finally gave in to demand to allow foreign rice imports into the court so that foreign markets would remain open to Japanese exports.

Deregulation of the financial sector, known as the Big Bang, began in April 1998 partly as a result of the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Regulations on currency exchange were ended in 1998. Fixed commissions charged by brokerages were ended in 1999. The Ministry of Finance’s informal "guidance regulatory system — for banks was replaced with a system based on stricter rules backed up through inspections. Under the old system the ministry relied on banks to report problems rather than investigating them themselves.

The scope and speed of deregulations and reform has been small and slow. New laws made it easier to spin off, split up or reorganize bankrupt companies and helped bring in some sources of capital New accounting and disclosure rules forces companies to cut spending and reveal hidden debts.

In May 2009, the head of the BJP urged banks to reduced their stocks and holdings in Japanese companies and said their failure to do so could undermine the domestic economy, citing the risks and hardships caused when stocks fall in value.

Japan’s Growing Asian Connection

The share of manufactured goods as a percentage of all Japanese imports has greatly increased since the mid-1980s, exceeding 50 percent in 1990 and 60 percent in the late 1990s, and this has spurred fears of a hollowing out of Japanese industry. Growing trade friction in the second half of the 1980s and the steep rise in the value of the yen impelled many companies in key export industries, notably electronics and automobiles, to shift production overseas. Manufacturers of such electrical products as TVs, VCRs, and refrigerators opened assembly plants in China, Thailand, Malaysia, and other countries in Asia where work quality was high and labor inexpensive. For such products, the market share of imported goods now exceeds that of domestic items. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In recent years, a rapid increase in manufactured imports from China has caused particular concern. Between 2001 and 2005, Japan’s imports from China rose by 170 percent. During the same period exports to China rose by an even faster rate, 235 percent. Moreover, the share of Japan’s trade occupied by China grew to 19.4 percent in 2010,surpassing the 15.4 percent held by the United States to become the largest of any country. Japan’s digital home electronics and automobile-related exports are robust, with total exports to China exceeding the 100 billion dollar level since 2007.

“Since 1988 Japan has run a continuous trade deficit with China. However, a large portion of Japan’s exports to Hong Kong end up being exported to China, and if this is taken into account and Japan-China trade is examined from an export basis, Japan is actually running a trade surplus. The simultaneous increase in the volume of both product exports and imports with China and the rest of Asia is partly the result of an international division of labor occurring as part of manufacturing globalization. Japanese companies export capital goods (machinery) and intermediate goods (components, etc.) to production facilities built through their direct investment in China, and then they import the finished goods back into Japan.

“At present there is still a vertical division of labor, with Japan specializing in knowledge- and technology-intensive modules and processes and China specializing in labor-intensive modules and processes. As China and other developing nations continue to improve their technical capabilities, however, the challenge for Japan’s manufacturing industry will be to maintain a comparative advantage in knowledge- and technology-intensive sectors.

Bank of Japan

Outsourcing, Downsizing and Moving Operations Overseas in Japan

Corporations increasingly have oriented themselves towards making profits, cutting costs and the bottom line rather than looking out for the welfare of their employees and other Japanese companies. Outsourcing, relying on foreign suppliers and and moving operations overseas have all become commonplace. Looking for ways to cut costs, Nissan, for example, started purchasing steel from South Korean manufacturers instead of more expensive Japanese suppliers.

Toyota, Toshiba and Sony and other corporation now have a large share of their production facilities outside of Japan, particularly in China. Japanese companies now manufacture more overseas than they export from home. Among the items that Japan imports are Honda cars, Sony televisions an Panasonic air conditioners produced in overseas factories, primarily in China and elsewhere in Asia. Hundreds of thousands of jobs in the United States are now tied to Japanese companies.

Laying Off Workers, See Economics, Labor, Labor, Unemployment, Unions

Hostile takeovers remain rare despite some well publicized ones. Business sometimes merge to cut costs and become more competitive or pool resources in specific projects and or products for the same reason. Occasionally foreign companies get a piece of the action as was the case with Renault and Nissan. Mergers and acquisition have traditionally been looked upon as gimmicky.

In 2007, laws were changed making it easier for companies to merge and launch takeover bids. The rule changes worried many Japanese companies that might be the target of hostile takeover bids from large foreign companies. The mid 2000s was a time when Japanese companies became increasingly interested in mergers and acquisitions themselves both at home and abroad.

Chinese factory

American-Style Competitiveness in Japan

In recent years the "Japanese way" of management has been replaced by more international styles. Japanese companies are looking more and more at American companies for ways to improve their competitiveness and productivity.

One executive told the Washington Post, "I think sooner or later the harmony that was with Japanese companies for a long time will diminish, because enterprises have to make profits. Japanese people don't like intense cutthroat competition. I myself don't like it, but there is no other way in the future." If the system does not change "Japanese companies cannot survive."

Japanese companies are 1) looking more at short-term results as a measure of responsiveness to a quickly changing economy, 2) giving bonuses and salary increases based on performance, and 3) reducing the size of board of directors and including more directors from outside the company so that decisions can be made quicker and reflect a broader range of viewpoints.

Koizumi Reform Drive

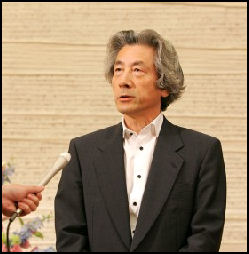

Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro Koizumi, Japan’s prime minister in the early 2000s, promised to change the LPD's traditional pork barrel politics, privatize state monopolies, eliminate bridges-to-nowhere public works projects and liquidate bad bank loans. He talked about diverting tax revenues earmarked for road construction to other purposes; said he would find money for the pension and health care systems; and said regional government should decide which projects should be built rather that the national government.

Koizumi pledged to make four major reforms: 1) reform the pension system, which was stressed from a rising elderly population and declining revenues: 2) reform local government’s fiscal conditions: 3) reform the four road-related public corporations: and 4) privatize the three postal systems. Koizumi also promised abolish or privatize public corporations such as the postal services savings system that have underwritten much of the economic activity in the 1990s but were very unprofitable.

Koizumi cut state pensions, raised health insurance premiums, and changed laws to allow companies to hire more easy-to-lay-off temporary staff at lower wages. Heizo Takenaka, Koizumi’s economy czar, led a tough but successful effort to clean up the economy and change the way of doing business. His greatest success was cleaning up the banking system. Takenaka was unpopular with industry leaders, bureaucrats and lawmakers and was accused of running the show with a “dictatorial” governing style and not compromising or even consulting with the groups affected by the decisions he made.

Lack of Reforms in Japan

Reforms have come slowly. Rather than encourage bloated companies to restructure, and making it easier for people to change job, the government still provides subsidies to companies to keep workers who are no longer needed. There has been a reluctance to foreclose on bankrupt companies and weed out corrupt officials because they were regarded as necessary to get the country back on course.

In some cases, antitrust legislation intended to dismantle cartels and spur competition between different companies within specific industries such as concrete manufacturing has not led to lower prices but instead has produced more mergers among the companies so that prices can continue to be artificially high.

While Japan stagnated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, South Korea, which enacted bold reforms in the 1990s, grew. The dulled sense of emergency in Japan was called the Boiling Frog Phenomenon, a reference to the fact a frog does not jump out of a pot of hot water when water temperature is raised so gradually the frog's loses it s ability to react.

For a shrift from tradition egalitarian and collective business to culture to one that is more individualistic and creative will require changes in society as a whole, beginning with the education system.

Most of the efforts to thwart Koizumi’s reforms came from within his party, the LDP, and the bureaucracy by old timers who were linked with construction and real estate interests and wanted to protect their pet projects and their supporters. People in Hokkaido, which receives the largest proportional share of government revenues for construction projects, were particularly upset about the reforms.

The construction industry that Koizumi said he wanted to dismantle was in many was key to keeping the LDP in power. When a government advisory panel on privatizing public highway operators called for strict limits on the construction of new highway its chairman resigned and walked out. Some pundits said if Koizumi went through with his reforms he would dismantle the LDP the same way Gorbachev dismantled the Soviet Union.

Recovery in Japan in the Early 2000s

They Japanese economy improved in the early and mid 2000s under Koizumi. Koizumi’s economics chief Heizo Takenaka, is largely credited as being the architect of Japan’s recovery. A former professor at Keio University, he devised the plans for the disposal of banks bad loans and postal privatization.

By some calculations Japan’s recession ended in February 2002 and this was followed by a period of growth that lasted until the late 2000s. Much of it was driven by exports which rose as proportion of GDP from 10.4 percent to 15.6 percent

In July 2003, it was big news when the Nikkei broke the 10,000 mark. There was optimism as Japan has weathered the SARS and Iraq crisis and growth figures were good. In 2004, there was healthy growth, spurred by strong business investments, strong exports, increased consumer spending and links with growth in China and the United States.

Banks have had some success disposing of their bad loans. Between March 2002 and March 2004, total bad loans were slashed from nearly $400 billion to $242 billion. Some of the success was attributed to the government-run Financial Services Agency, which forced banks to account for risky loans and stop lending to zombie companies.

Japanese investors began bringing their money back home and foreign investors began finding bargains in Japan. Japanese companies maintained their research budgets even when times were bad and remained competitive, Between 1992 and 2004 Japan spent more on research and development as a percentage of its total economy than any other developed country.

Recovery Continues in the Mid 2000s

By 2005, many felt Japan’s economic problems were behind it. Financial problems had been settled; the end of deflation was in sight; company fundamentals looked good; pent-up demand for investment and consumption was occurring. The job-to-applicant ratio was 0.99, which was seen as a sign that was a for everyone who wanted one, even though unemployment was 4.4 percent. Tax breaks initiated as a stimulus in 1999 were ended in 2005.

Consumer confidence rose. Restaurants were full; taxis were hard to find; buildings and houses seemed to be going up everywhere. University graduates were welcomed with lots of job opportunities. Wages and corporate profits were rising. Land prices in the major cities were up. Overseas money pushed bull runs in the stock market in 2005-2007. Purchases if Bubble-era luxuries such as expensive watches, works of art, sumptuous hotel suites, and meals at expensive restaurants were on the increase. Rising prices was seen as a good sign, signifying that deflation was being tamed.

A record of 58 months of sustained growth lasted from February 2002 to November 2006. It was the longest period growth in the post war period. The boom was called the “boom without feeling” as companies were making record profits wages for workers and salary men remained stagnant and in some cases went down.

Many attribute the turnabout to the pressures of globalization, the threat of China and the realization by Japanese businessmen that stock market was not going to return to 1980s levels and bail them out. Beginning in the 1990s Japanese companies had began shifting production abroad, cutting costs, shedding extraneous businesses and reducing debt. The government stepped up efforts to attract foreign direct investment which was not needed in the past.

Growth was 2.7 percent in 2005 and 2.1 percent in 2006 and 2007. The expansion was led primarily by robust domestic demand and trade with China. This was seen as a sign that recovery was for real. Japanese banks had better shape as a result the strong economy and their success shedding bad loans. In May 2005, seven major banks said they had met government targets in slashing bad loans and making healthy profits. In 2006, the stock market soared to six year highs, land prices increased for the first time in more than a decade and deflation was declared all but dead.

Many companies benefitted from foreign sales and a weak yen. In February 2007 the Nikkei went above 18,000 for the 1st time in 7 years and hit a high of 18,261.98 on July 2007. On the same day The Topix hit a 15 year high of 1,802.9. In May 2007, the jobless rate to a nine-year low of 3.8 percent. In August 2007 land prices rose 8.6 percent nationwide.

stock market growth

Stock Market Boom in Japan

A bull market ran from 2004 to 2006. The Nikkei was the best performer of the world’s 10 largest stock markets in 2005. It and Topix rose over 40 percent. The Nikkeo gain of 40.2 percent was the largest gain since 1986 and closed the year over 16,000. Topix rose 43.5 percent. The gains were way beyond what even optimist predicted.

The surge in investment was also attribute to affordability and equity of trading, boosted in part by the ease of trading on line with Internet brokers such as Monex and E*Trade Japan, In 2005, individuals accented for 50 percent of trades of the Tokyo Stock Market. Much of the trading is conducted by individual day traders, many of them housewives and young salarymen, using their cell phones pr laptop computers. The market is very competitive. The fees for uses is low as are the profit margins for brokers. The trend was similar to what happened in the dot.com bubble and collapsed in the United States

Foreign invertors also played a part in the boom. They bought $86.7 billion worth of Japanese stocks. The dollars 15 percent rise against the yen was one reason Japan seemed more attractive, Koizumi success pushing through reforms on the Japanese postal system was also viewed positively.

Problems Emerge in the Late 2000s

The recovery was regarded as fragile. Growth was propelled mainly by an increase in exports. The economy was dogged by weak consumer demand. Wages were not increasing and consumers didn’t feel like spending. Savings increased from 12 percent to 14 percent.

By early 2007 Japan was showing signs of falling back into recession while being hit with some its highest inflation in 27 years caused mainly by higher fuel and commodity prices, which also reduced profits and the trade surplus. Japan still had the world highest public debt load, at 151 percent of GDP. The cost of paying the debt ate up a fifth of government spending.

In January 2006, after reaching a five year high, the Tokyo Stock Market was forced to close early by 30 minutes because of massive sell off triggered by a raid on Livedoor headquarters. Trades were slowed because the computer system reached it capacity. The market was down 5.7 over two days over rumors of the aid and then the raid itself. See Economics, Business, Banks, Livedoor and Stock Market, Stock Market Glitches

Koizumi’s successor Shinjo Abe didn’t pursue reform as aggressively as Koizumi. He hired well-respected veterans for top financial posts. The problems Abe faced included taxation problems, growing gap between rich and poor, huge government debts, shrinking population, tense relations with Asian trading partners and reliance on the economies of the United States and China. Abe recognized the need to develop entrepreneurship and give more opportunities but gave few details on how to achieve these goals. There was still a need to do something about the huge debt and creating more domestic demand.

Strong Yen and Inflation in 2008

In March 2008, the dollar broke the ¥100 mark, dropping as low as ¥95 at one point, for the first time since 1996. In June 2008, the Euro hit an all-time high against the yen of ¥169 . There were concerns that a strong yen versus the dollar would hurt Japanese exports by raising the price of Japanese goods and pricing them out of their markets.

By then Japanese economy was beginning ti falter and growth was slowing due to high inflation fanned by huge energy and commodity costs. Inflation rose at their highest rate in almost a decade. Stocks fell. Consumer spending was down. Housing starts plummeted. Foreign reserves fell. The trade surplus turned to a deficit, Analysts said the Japan’s problems were mostly self-inflicted and not the result of U.S. subprime loan crisis.

Growth from January to March 2008 was 3.6 percent on the back of high capital spending and exports. But in the second quarter GDP shank 0.6 percent and consumer sentiments were at a record low as gasoline and food prices rose while wages remained stagnant.

As the year wore on the subprime crisis began having more of an affect on Japan. Banks and security firms wrote off more than $100 billion in assets worldwide because the crisis. Property values in Tokyo and elsewhere began to fall as investment money shrunk, forecasts of future growth were lowered, the trade surplus shrunk In August 2008, the Fukuda government announced a ¥11.7 trillion stimulus and one-year tax break package to boost the economy.

In July 2008, consumer prices rose 2.4 percent, the highest in 16 years. In July and August wholesale prices rose 7.3 and 7.2 percent respectively, the highest rates since 1981 mainly due to high energy and material costs. Prices also jumped for basic things like milk, cooking oil, noodles.. Consumer responded by changing their eating habits and buying cheaper products. Manufacturers responded by raising prices and putting less food in their products. Luxury restaurants and designer good stores fell on hard times while ¥100 stores and eateries that offer cheap meals did well.

Many economist felt that inflation coupled with a credit squeeze caused by subprime crisis was a good thing for the Japanese economy. According to Financial Times: “The rise in headline inflation is an opportunity...because it implies a fall in real interest rates. As long as minimal interest is negative, which should stimulate economic activity and create the expectations that prices will continue to rise in the future.”

China Replaces Japan in 2010 as No. 2 Economy

In the April-June quarter of 2010, China surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest economy behind the United States as it chalked up $1.337 trillion of GDP in that period compared to $1.288 trillion for Japan according to Japanese government statistics. For Japan, the statistic reflected a decline in economic and political power. Japan has stood as the No. 2 economy behind the United States for 42 years. In the 1980s, its rapid growth even led to talk of the Japanese economy’s overtaking that of the United States by 2010.

China’s No.2 status was formalized when data for all of 2010 came in. Japan’s nominal GDP — the total value of goods and services without accounting for inflation — for 2010 amounted to $5.47 trillion, according to Japanese Cabinet Office. That compared with to a $5.88 trillion economy for China. The latest numbers were further evidence of China’s rapid ascent as an economic superpower. Just five years before, China’s gross domestic product was around $2.3 trillion, about half Japan’s.

Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said, “We are not engaging in economic activity to vie for ranking but to enhance people’s lives. From that point of view, we welcome China’s economic advancement as a neighboring country....the important thing is to incorporate such vitality” to make Japan’s economy grow. Senior Mitsui executive, Osamu Koyama, told Roger Chen of the New York Times: “We’ve been telling people for years we were No. 2, ever since we overtook Germany, and it hasn’t given us much benefit. “

According to the New York Times, “While Japan’s economy is now mature and its population quickly aging, China is in the throes of urbanization and industrialization. Still, China’s per-capita income is about $3,600, less than one-tenth that of the United States or Japan... Japan’s economy, however, has benefited from China’s rapid growth, initially as businesses shifted production there to take advantage of lower costs, and as local incomes rose, by tapping an increasingly lucrative market for Japanese goods.”

An editorial in The Strait Times read: “The Japanese can still hold their heads high. No amount of moaning at being overtaken by China would negate the fact that theirs remains a model rich nation others want to emulate, and that it is probably among the most civilized of societies. The latter category counts in evaluating human progress. The societal coarsening that has blighted China with the onset of sudden riches is a serious deficiency that can only get worse. And the Japanese economy remains innovative in spotting trends. Its brands are so strong Toyota has not lost the confidence of overseas car buyers despite a spate of production flaws. Japan has lots more to offer and its people need not think of the country as being in rapid decline.”

Image Sources: 1) Shugin House of Representatives site 2) Wikipedia 3) China Labor Watch 4) Kantei, Office of Prime Minister 5) Tokyo Stock Market 6) markun.cs.shinshu-u.ac.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2012