JAPANESE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL LIFE

The elementary school day lasts from around 8:15am to 3:00pm, Monday through Friday, but the finishing time often varies from day to day. Although the school day is longer than in the U.S. school day, Japanese students generally have more free time and breaks during their time at school. Sports clubs, even ones for elementary school, sometimes require students to show up for practice early in the morning or stay at school until 6:30 or 7:00pm.

The students have the morning homeroom period from 8:15 to 8:30. Then, they have four 45-minute periods in the morning, with three 10- to 15-minute breaks, starting the first period from 8:35 to 9:20 and then a 10-minute break from 9:20 to 9:30. After finishing the fourth period at 12:15, they have school lunch together in the homeroom. Then, they clean classrooms, corridors and playgrounds from 1:00 to 1:20, and have a long break from 1:20 to 13:45. The fifth period starts at 13:50, and the sixth period ends at 3:45. The afternoon homeroom period lasts from 3:45 to 3:55 before a school day ends. School lunch has been provided to public elementary schools since 1952, and to public middle schools since 1956 nationwide. As of 1997, 99.4 percent of elementary school students and 82.1 percent of middle school students have school lunch (Ukai et al. 2000:19). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

A March 2003 survey of 838 elementary students (via questionnaires distributed to schools in Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama prefecture) showed that most children enjoyed elementary school, with 46.1 percent replying that it was "very fun," 30.3 percent that it was "somewhat fun" and 17.6 percent that it was "more fun than not." However this feeling was clearly not shared by all students: 5.9 percent found elementary school either "not very fun" or "not fun at all." As for how much they had understood of their studies in the six years at elementary school, 37.6 percent replied at least 80 percent, 31.5 percent replied between 70 to 80 percent, but approximately 30 percent had entered junior high school without much confidence in what they had learned. Although nearly half of the students reported enjoying the 6th grade the most, higher percentages of bullying and truancy are indicated in the upper grades, with 40 percent having been subject to bullying or peer group exclusion. As students advance in grade, it appears that students become very polarized in their experience of school, either experiencing it a fun or difficult environment. [Source: Daily Yomiuri, education-in-japan.info/sub106.html]

Enrolling a Child in a Japanese School

To enroll a child who has newly arrived in Japan, go to Ward Office (Ku-yakusho) with your child and apply for an alien registration (gaikokujin tourokusho) on behalf of the child. You must bring proof of your address as the school your child is going to attend is designated according to the address. No photograph is needed. When you have received the alien registration card, proceed to the Board of Education (kyouiku iinkai) office in Ward Office. The kyouiku iinkai office will telephone the school your child will attend to make an appointment for the parents and child to meet the principal (kouchou mensetsu), usually the next day. School can usually commence immediately after the interview. [Source: Daily Yomiuri, education-in-japan.info/sub106.html ////]

When a child has moved and are changing address from within Japan: parents need to visit the ward office to submit a change of address (juusho henkou). The rest of the procedure for registering with the new school is the same as above. Should your child be already resident in this Ward and you wish to transfer from an international school, parents should take the child's alien registration card to the Board of Education office to begin enrollment procedures. The child does not have to be present. ////

Elementary School Entrance Exam in Japan

Exam hell and competition to get into the right school begins at a very early age for some Japanese children, whose families invest large sums of money to prepare them for entrance exams for prestigious kindergartens and elementary schools that in turn prepare students for exclusive secondary schools and universities. Japan’s 52 national universities have 73 elementary schools affiliated with them.

The kindergarten entrance exams tests children on their knowledge of shapes, the color of fruit, number sequences and polite behavior. An estimated 500,000 per-schoolers are enrolled in cram schools to prepare them for the tests. Some children begin studying for these exams when they are 6 months old, learning activities like how to open and close their hands.

Toshiyuki Shiomi, an education professor at the University of Tokyo told AP: "To pressure kids who can't even express themselves yet to do something they don't want to do will end up warping Japanese society."

Some families make large “donations” to exclusive schools. Waseda Jitsugyo, an elementary school affiliated with Waseda University, revealed that parents on average donated $33,000 to the school in addition to normal tuition fees and expenses. In some places parents have camped outside school offices to get into schools. In Yokohama, parents camped out 10 days to enroll in private kindergartens in Kohuku New Town in Tsuzuki and Aoba wards.

Parents often form lines in front of exclusive kindergartens and elementary schools in the wee hours of the morning to submit applications for the schools even though they are told that waiting in line like that gives them no advantages and admission is determined by performance on a test and by lottery.

Japanese School Year

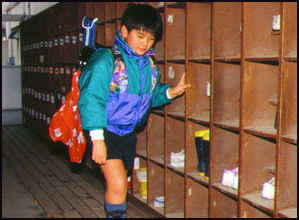

school day begins

with putting shoes in

special shoe boxes

The Japanese school year extends for 210 or so days — compared to 180 in the United States, 251 in China, 220 in South Korea, and 214 in Israel. The Japanese academic year extends from early April to the end of March and is divided into three terms: 1) April to July, 2) September to December, and 3) January to March. There is a six week vacation in the summer, two weeks in winter and two weeks in spring. Some schools follow a two-term schedule. There is strict cut off date for which grade a kid goes into with those born in March going to one grade and those born in April going into another. Educators have recommended that the start of the school year be changed from April to September or October to be in line with the rest of the world.

Miki Y. Ishikida wrote in Japanese Education in the 21st Century, “Japan has had much longer school days than the United States, though the difference has been shortened. In the United States, most public schools are required to be in session 180 days a year, generally from September to June, with a three-month summer vacation. In 1997-1998, 51 percent of elementary schools and 66 percent of secondary schools provided summer programs (DOE 2000b). Recently, many schools have switched to “year-round” programs that have three-week vacations after each quarter, in order to promote higher educational achievement. In Japan, the school year had been gradually reduced to 210 days, in accordance with the five-day school week from April 2002. [Source:Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The Japanese make more of a big deal about the beginning of a child's education career than the end. Large celebrations are held and expensive presents are given when a child enters kindergarten not when he or she graduates from high school or university.

Japanese students often go on more field trips than their American counterparts. Young students often make annual trips to farms to harvest sweet potatoes and rice. In many school districts fifth graders take a mandatory overnight ski and sledding trip and sixth graders do an overnight trip to Hiroshima, often combined with an outing to a theme park. A popular trip in the Tokyo area is one day at the World-War-II-era, 1.6-kilometers underground tunnel system at the Akayama air raid shelter and one day at Tokyo Disneyland. Around 30 school days each year are taken up with field trips, cultural festivals and other ceremonies.

Japanese School Week

aerial view of a typical school The gradual transition from a six-day school week to a five-day week was completed in 2002. Before the early 1990s there was school every Saturday morning. The five-day school week was introduced once week a month on 1992 and expanded to twice a month in 1995 before going into full effect in the 2002-2003 school year. Many private schools, however, continued to hold Saturday classes, and in recent years some public high schools have obtained special permission to reintroduce Saturday classes to give them more time to cover the necessary subjects.

The five-day school week has resulted in a reduction of class hours in all subjects. To compensate somewhat students are required to take three days of an extracurricular activity such as badminton, rugby or debating. Sometimes these activities are scheduled after school. Sometimes they are scheduled on the weekends.

Surveys have found that about 70 percent of all students like the five-day school week. Among those who don’t like it are 12-year-olds who worry that the new system will jeopardize their chances of getting into a good university. Other have said that without school they get bored. Some parents have complained that students were already spending too much time playing video games and fooling around and less school and study time was the last thing they needed. Many private schools have kept the six-day school week. Other tried the five-day week and then went back to the six day week.

The introduction of the five-day school week was also viewed as a challenge to families and communities to come up with things for children to do in their free time. In some areas, volunteers have offered classes in handicrafts, pottery, calligraphy and games like go and shogi. Studies have shown that more children are participated in outdoor activities on the weekend but a large number still spend a lot of time watching television, playing video games or sleeping more.

The five-day school has been blamed for declines in academic performances. There has been discussion of reforming the five day school week by requiring more classroom hours by shortening the vacations or extending daily class hours to make up for the hours lost by dropping Saturday classes.

Clean Classrooms in Japan

“Souji” ("honorable cleaning") is a period of about 15 minutes each day when all activities come to a stop, mops and buckets appears and everyone pitches in cleaning up. Often the teachers and principals get on their hands and knees and join students.

Japanese schools don't have any janitors because the students and staff do all the cleaning. Students in elementary school, middle school, and high school sweep the hall floors after lunch and before they go home at the end of the day. They also clean the windows, scrub the toilets and empty the trash cans under the supervision of student leaders. During lunchtime, sometimes donning hairnets, students help serve the meals and clear away dishes.

A member of the Board of Education in a town in Hokkaido told U.S. News and World Report, “Education is not only teaching subjects but also cooperation with others, ethics, a sense of responsibility, and public morality. Doing shores contributes to this. Besides, if students make a mess, they know they have to clean it up. So naturally the try to keep things clean.”

“Cleaning is just one of a web of activities that signal to children that they are valued members of a community,” Christopher Bjork, an educational anthropologist at Vasser Collage told U.S. News and World Report.

School Lunches in Japan

making school lunch All primary school kids eat school lunches, and about 8 percent of middle school students do. Japanese students eat their lunches in the classrooms (there are no cafeterias in Japanese schools) and help prepare and serve school lunches. Food is served from stainless serving trays and large pots by students, who sometimes wear surgical masks, aprons and hair protection. The food is often prepared in a kitchen on one floor and transported to the classroom on special carts using special elevators.

Typical Japanese school lunch meals include beef with potatoes and vegetables; cold noodles with mixed nuts and melon; curry and rice with salad and pickles; fried squid with fried potatoes and soup; and eel sushi with soup and fruit in jelly. A typical school lunch is comprised of miso soup, spinach and Chinese cabbage in almond paste, “ natto” (“fermented soy beans”), rice and milk and has 621 calories and cost $1.68.

Fees for school lunches is around ¥3,900 a month in primary school and ¥4,500 a month in middle schools. Children are expected to eat everything. Once a teacher was so outraged by finding some rice in a trash can she made her eat eight-year-old students eat it.

Health Checks, Pinworms and Air Conditioning in Schools in Japan

Students get mandatory free health checks at school. Their hearing, vision, heart and lungs are checked. Dentists check their teeth. Urine samples are collected and tested for diabetes and urinary-tract infections. One of the more unpleasant experiences is the pinworm test which is done at home.

Pinworm are tiny parasites that cause rectal itching and other health problems. They are found in around 4 percent of all students. Female pinworms live in the appendix and emerge from the anus to lay their eggs. Testing involves placing special adhesive tape on the a student’s anus on two consecutive days and taking these tapes to a laboratory and checking them under a microscope for eggs.

Classrooms are not heated or air conditioned. In the winter students show up in their winter coats, scarves and gloves. Sometimes their ears and noses turn red and they can see their breath. In July, they endure sweltering classrooms without even fans.

Most schoolyards are covered in dirt, asphalt or crushed limestone. In 2006, a decision was made to put turf on 2,000 primary and muddle schools in the Tokyo area over the next 10 years. The move was made to improve the environment for children’s outside activities and combat the urban heat island effect.

School Class Size and Student Organization in Japan

The number of students in each classroom is generally larger than in the United States. The teacher to student ratio is listed at 21 to 1 for Japan but a typical primary school class has around 31 to 35 students; a typical middle school class has 36 to 40 students; and a typical secondary school class has 45 students. When asked what they think is an ideal class size most teachers say between 21 and 25.

Teachers organize student into groups with student leaders and other members of the group using peer pressure to keep the group members in line. There is an emphasis on functioning harmoniously as a group. If one students acts up or doesn’t do chores, it is up to the other students to pressure him to act right,

The students in Japanese schools are generally better behaved and there are far fewer discipline problems than in the United States. Studies have also shown that Japanese students on average spend about one-third more time learning each class period than American students do.

Students identify very closely with the kids in their grade, arguably more so than in the United States. Teachers change classrooms rather than students, leaving students with the same group all day. Substitute teachers often are not necessary because the students can direct their own activities.

Japanese kids have a lot of summer homework. Traditionally it has been regarded as shameful for students to ask too many questions in the classroom. Senior (“sempai”)-junior (“kohai”) relations are important in defining how students behave with kids in their class and with older and younger kids, teachers and administrators. See Children.

To improve the quality of education some schools have started stressing “Finnish-style” classes on which small groups discuss of a variety of topics, such as competition and personal worries, the result is that students are more willing to express their opinions.

Swimming Lessons in Japan

Nearly every elementary school in Japan has an outdoor swimming pool. In elementary school swimming lessons are part of the school year curriculum and are offered free during the summer. The goals is teach swimming to kids so they can enjoy the sport and feel safe around water.

In June when the swimming lesson start parents are given detailed handouts of what is expected of them and their children. Students must wear regulations swim suits and caps with their name, grade and class written on them. Parents are supposed to check their child's temperature every day and mark it on a card that says their child is healthy enough to swim that day. Parents put their hanko (chop) on the card. If a child does not have the card he or she can not swim that day.

Students change into their swim suits at school, with girls in one classroom and boys in another. They carefully stretch and shower, and sometimes walk through a hip-deep pool of disinfectant and finally enter the pool about 60 at a time. The kids regular classroom teacher dons a bathing suit and teaches the classes. The students are taught different skills and proceed up a ladder of 15 ranks.

Students in many places are required to swim a certain distance such as 100 meters, 200 meters or 400 meters. If they can’t they have to attend a special summer training program.

Westerner’s View on Japanese Primary School Life

Lynda Watson, a Briton with a New Zealander husband and two primary-school-age children, wrote in education-in-japan: “What have we learned from our first year at a Japanese School? Well, for a start the teachers are great! At least they are at our school. They don't shout and yell and seem to go around with smiles fixed on their faces. How do they do this? I'm not exactly sure. The discipline seems to be firm. Even the first graders are able to successfully organize their own classes should the teachers have to disappear for a while. The children are friendly and helpful. [Source: Lynda Watson, education-in-japan.info/sub106.html, February 10, 2000 |=|]

“What else? Well, you need to be very organized. Once you get the hang of it, this isn't too hard. If I can manage it, then anyone can. For a start there is the uniform. This has to be perfect, complete, conforming and properly labeled with the correct colored labels and names and grades entered correctly...Then, there is the schedule. This daunting piece of paperwork tells you what your children are to study the following day. The Japanese system of making the children bring home all text books and then the next day just taking in the ones that they require involves a bit of forethought and an ability to decipher teachers' instructions. There was the time that they were instructed to take in green tea in a flask. Well, they don't drink green tea, nor any tea in any form. However, it was cold and I thought that the idea of something warm in a flask was brilliant, so I sent in some delicious hot chocolate milk. A little difficult to gargle chocolate milk! We received a note back: "no chocolate drink thanks" (well it was worth a try)! The teachers told us afterwards that they had a good laugh over that one. |=|

“The Japanese are so well organized with everything that things such as pen sets, paint sets and music equipment, etc., are purchased in beautifully bagged or boxed packages. I love them! It makes carrying several items at once to school quite easy, but I can't understand why those very expensive school bags cost so much when you can get so little in them. Maybe it's the way I pack? |=|

“We have found the local people very helpful and have been lucky enough to get school uniforms for free as they gave us their children's old ones. It makes sense when your children are shooting up. We know they are growing fast because they are regularly weighed and measured at school, and the marks on the graphs are rising in proportion to the hems of their trousers. |=|

“School lunches are lovely. I have been lucky enough to be invited to a couple. The sense of occasion is wonderful as each child prepares their tablecloth, chopsticks, etc. They eat delicious and healthy food, and an extensive explanatory chart is sent home every month to tell us exactly what they are receiving every day. I wish those cooks would come work at my house! The children weren't so impressed at first. They missed the sandwiches and snacks that I used to throw together. However, their tastes have changed over the year and they now quite happily devour things that they wouldn't have looked twice at before. If they had been at home all the time, I doubt I would have been able to get them to try anything different. Peer pressure counts for a lot! |=|

Entrance Exams for Elementary School Kids to Get Into Middle School

These days many elementary school are enduring exam hell to get into prestigious state-run or private middle schools. Children put in long hours in juku in forth and fifth grade to prepare for these exams and shift into overdrive in the sixth grade. Because the tests are given in January and February, their parents enroll them in intensive study session during their winter vacation that offers classes on the weekends and even New Year’s Day, the biggest holiday of the year in Japan.

The questions on the exams to get into the private middle schools are very hard. They require knowledge of current events, advanced math and kanji (Chinese characters) that aren’t taught in middle schools. Some Americans who have looked at the test said the question are more difficult than those on SATs.

The reason for this is that if a student can get into a good private middle school they can avoid exam hell down the road. Most middle schools are affiliated with high schools. Since these high school get most of the students from the middle school, the middle school students don’t have to take the rigorous high school entrance exams. And since many private middle-high schools are affiliated with universities and many of their students come from affiliated high schools, the high school students can even get out of taking the exhaustive university entrance exams.

Parents increasingly feel that normal public schools offer a substandard education. Public middle schools in particular have a bad reputation and many parents are willing to spend a lot of money to send their kids to private middle schools. There are magazines devoted to helping parents boost the test scores of their children. In 2006, over 50,000 12-year-old students sat for exams for 25,000 places in private schools.

After-School Activities for Elementary School Students in Japan

Elementary school students go home around 4:00 p.m., though the first- and second-graders go home earlier. For first- to third-graders, about half of elementary schools provide after-school programs for children whose mothers or guardians work. After school and during holidays, many children participate in their local Children’s Association, and community- or school-based sports clubs such as soccer, baseball, basketball, volleyball, and table tennis, which are under the supervision of parents or local volunteers. According to a 2000 survey, about half of fourth- to sixth-graders (44.6 percent) join their neighborhood-based Children’s Association. More than forty percent of boys (40.2 percent) and 19.4 percent of girls participate in a sports club. One-third (34.3 percent) do not join any associations (Naikakufu 2001b). Public schools open their gymnasiums and school grounds for private sports clubs that are registered with the municipal administration. Some teams practice two or three times a week. For example, one soccer team practices from 1:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. on Saturdays and from 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. on Sundays. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Most children participate in community festivals. Parents’ involvement in community activities effects their children’s participation. Two-thirds of children whose parents joined a festival participated in community festivals, while less than half of all children whose parents do not join a festival participate (So-mucho- 1996:100-101, 223). The MOE started to subsidize local educational activities during holidays and after-school in April 2002. Children can participate in community activities such as making traditional crafts with the elderly, working in the fields with farmers, collecting plants and insects, and learning techniques in factories, rather than going to cram schools, watching TV, or playing games at home (AS August 30, 2001). ~

After-School Programs at One Japanese Primary School

After-school programs provide childcare for children from first to third grades whose mothers or guardians work. Working mothers who cannot find a caregiver may send their children to after-school programs if the school or the community has one. At school or in public facilities, the children do homework, play with friends, have snacks, and relax under the supervision of after-school teachers until 5:00 p.m. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

In 1966, the MOE started a small-scale subsidized childcare service for latchkey children. In 1975, the Ministry of Health and Welfare initiated “the childcare club” in urban areas. When most mothers with small children stayed home in the 1960s and 1970s, many full-time working mothers were from low-income households. Therefore, the after-school programs were regarded as a social welfare program for poor children. Over the past two decades, the number of working mothers with small children has been increasing. Now that the half of the mothers of first- to third-graders work outside the home, after-school programs are in high demand. ~

After the childbirth rate hit its all-time low (the so-called “1.57 shock”) in 1989, the government took a serious look at childcare in order to stop the falling birth rate. The government recognized the importance of after-school programs in the 1994 Angel Plan and in the revised Child Welfare Law in 1997. According to a 1995 survey (N=718) of full-time working mothers with children in first through third grades, 44.2 percent of mothers who did not live with their parents or in-laws sent their children to the after-school programs (Fujin Sho-nen Kyo-kai 1995:14). ~

According to the National Federation of After-School Programs survey, by May 1, 2002, there were an unprecedented 12,825 programs for about 490,000 children. More than 60 percent of after-school programs are operated by local governments and social welfare associations. Almost half of after-school programs (43.3 percent) are school-based, 19.3 percent are in children’s centers, 18.1 percent in other public facilities, 9.1 percent in private homes, 6.3 percent in corporate facilities, and 3.3 percent in other places. More than half of elementary schools (53.3 percent) have after-school programs. Still more after-school programs are needed because only 170,000 of 420,000 first-grade children from nursery schools attend after-school programs (Zenkoku 2002). ~

The government needs to support more of these programs. The government subsidizes 3 million yen (one-third each from the national, prefectural, and municipal governments) per year to programs with at least 20 children. The Ministry of Health and Welfare decided to add subsidies to the programs that operate more than 6 hours a day and after 6:00 p.m. to meet the needs of mothers who work late (AS September 21, 1998). After-school programs can operate efficiently and at minimum cost because public schools and community facilities are available at no cost for after-school programs. Moreover, caregivers can be recruited from a large pool of highly educated homemakers, some of whom hold teaching certificates. The government plans to add 15,000 more after-school centers for first- to third-grade children by 2004. Half of these after-school centers will be run by the private sector and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) (AS May 21, 2001). ~

After-School Program at Momo Elementary School

The Department of Lifelong Education under the Marugame Board of Education supervises after-school programs.8 An after-school program for latchkey children started at one elementary school in downtown Marugame City in 1966. In 1967, after-school programs operated in four urban elementary schools, and in six rural elementary schools during the planting and harvesting seasons. These rural programs finally adopted a regular daily schedule in 1996. In April 1999, 19.3 percent of students (433 students) in Marugame attended after-school programs in their elementary schools. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The after-school program at Momo Elementary School in Marugame operates from 1:00 to 4:30 p.m. on weekdays. Two after-school teachers take care of 27 first- to third-graders. There are no after-school programs during spring and winter vacations, but there is a two-week program during summer vacation. During summer vacation, the program runs from 9:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. for four weeks. Only ten children attended after-school programs during summer vacation in 1997. One teacher said to me that offering childcare services only in the morning did not make much sense because it did not help full-time working mothers. ~

The after-school program operates in a small building with one large tatami mat room at the corner of the school grounds. Momo Elementary School has one of the oldest after-school programs, and that is why this facility is rather out-dated. The new after-school programs in other schools have much better facilities. In Momo, the children sit on the floor along three long wooden desks. There are two stoves, a bookshelf with children’s books, cards, comic books, origami, an organ, a sink for washing hands, and a shoe rack at the entrance. The maximum number of students per teacher is 40, the same size as a regular class. In the 1997-8 school year, 41 children were officially registered for this program. Therefore, there are two teachers for this club. ~

After school, children entered this building, saying, “I am home” (tadaima). They began to do their homework, and asked one of the teachers for help if necessary. After finishing their homework, some children went out to play on the school grounds. When it started raining, they came inside. Three boys played with blocks, two girls played with cards, one girl read comic books, three girls drew pictures, and two girls played at cat’s cradle with the teachers. One teacher said that the children usually liked to play in the schoolyard, but they stayed inside because of rain. Snack time was at 3:30. All of the children looked forward to it, but they had to have finished their homework if they wanted a snack. They chose four kinds of snacks from rice crackers, cookies, tangerines, candies, and so on. ~

One boy did not want to do his homework. The teachers tried unsuccessfully to get him to sit down and do his homework. They threatened not to give him any snacks. He had not received a snack the day before. He did not finish his homework, but the teachers gave him a snack anyway. The teachers could have been stricter, but the after-school programs foster a more relaxed attitude between teachers and students. After-school teachers are more like baby-sitters than classroom teachers. ~

Private Lessons (Naraigoto) and “Cram Schools” (Juku)

Parents are concerned about the academic achievement of their children, and encourage them to earn the highest grades, apply to better high schools, attend selective colleges, and eventually land well-paying jobs. Mothers are usually the ones who help their children study, and create favorable study environments for them at home. The majority of children have their own study room and desk. Many parents send their children to private lessons (naraigoto) to learn swimming, calligraphy, and piano. In addition, they buy worksheets and workbooks for their children and send them to “cram schools” (juku). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Since the 1970s, after-school private lessons for piano, calligraphy, swimming, abacus, and English conversation have been popular among elementary schoolchildren. In 2000, male elementary school students attended after-school lessons for (in descending order) swimming, piano, and calligraphy, while female students preferred piano, calligraphy, and swimming (Japan Information 2002). When they enter middle school, many middle school students stop taking music and sports lessons, and attend private study classes, “cram school” (juku) instead. ~

According to a 2000 study of educational expenditures, one-third of elementary school students (36.7 percent) attended juku, and parents spent on average 119,000 yen per year for juku (Monbukagakusho- 2002c). The juku for elementary school children usually operates informally in the private home of an individual juku teacher, often a retired teacher or a homemaker. Children attend juku late in the afternoon several times a week, or every day. Children review their schoolwork by doing homework and studying workbooks with juku teachers. Many of these teachers are homemakers who have teaching certificates but did not become teachers or who retired early to raise children of their own. They start a juku in their homes after their children have grown up. The juku helps elementary school children review schoolwork and homework for relatively low fees. In this sense, the juku plays an important role in supplementing children’s schoolwork. ~

Japanese Elementary School Students At Home

At home, a typical elementary school child studies for thirty minutes to one hour, watches TV for three hours, and also plays computer games. According to a 1999 survey of fourth to sixth graders, almost half (41.8 percent) studied for thirty minutes, one-fifth of them (19.1 percent) studied for one hour, a few of them (3.5 percent) for two hours, while one-third of them (33.2 percent) did not study the day before the survey. Also, one-fourth (24.9 percent) of elementary students watched TV or videos, or played games for two hours, another one-fourth (24.5 percent) did so for one hour, and 19.4 percent did so for three hours. More than one-third (37.1 percent) said that they did not play with friends the day before the survey (So-mucho- 2000b:64-66). According to a 2003 survey, 62 percent of elementary school children use the Internet (AS June 5, 2004). According to a cross-cultural survey in Japan and the United States, the fifth graders in Sendai, Japan spent six hours a week on homework, while the fifth graders in Minneapolis spent four hours a week (Stevenson and Stigler 1992:54-55). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Parents with only one or two children spend more time helping their children excel at school. Many mothers check children’s homework, notebooks, tests, and school journals every day. Teachers contact parents every day through classroom handouts, and/or daily journals. Students write a daily schedule and make entries in a daily journal, in which teachers and parents add comments of their own. The Parents’ Associations at elementary school are generally active in organizing school events, such as a sports day. PTA meetings are usually held after school visitation day when parents visit and see their children’s classes at least once a trimester. Nowadays schools try to have school visitation day on the weekend so that both parents can visit the classes. As the number of working mothers increases, fewer mothers have time to join the Parents’ Association. Many PTA meetings are now held in the evening when most parents can attend. Parent-teacher conferences are held at the end of each trimester to discuss children’s school performance and behavior. Many schools have scheduled an open school day when schools invite parents and community residents to school events, such as a sports day. ~

The positive and active involvement of parents contributes to the academic success of children. The correlation between parents’ educational level and children’s expectations is remarkable. Sixty-two percent of children in the fourth to ninth grade whose fathers are college graduates plan to attend college, while only 26 percent of children whose fathers are middle school graduates plan to attend college (So-mucho- 1996:169). ~

About half of fourth to sixth graders plan to attend college. According to a 1999 survey of fourth to sixth graders, about 38.5 percent of boys plan to attend a four-year college, 7.2 percent plan to attend a junior college or specialized training college, while 40.1 percent want to work after high school, and 10.4 percent have not yet decided. Comparatively, about 34 percent of girls plan to attend four-year colleges, 18.4 percent to junior colleges or specialized training colleges, while 35.1 percent plan to work after high school, and 12 percent have not yet decided (So-mucho- 2000b:61). According to a 1995 survey of fourth to sixth graders, many boys want to be a professional sports player (25.3 percent) or company employee (5.6 percent), while 38.2 percent are not sure. Among girls, the most popular occupation is teaching (12.3 percent) and the next most popular is nursing or care-giving at a daycare center and kindergarten (9.7 percent), while 37.5 percent are unsure (So-mucho- 1996:72-73). ~

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~; Education in Japan website educationinjapan.wordpress.com ; Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), Daily Yomiuri, Jiji Press, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014