GOALS AND ISSUES WITH JAPANESE EDUCATION

The Japanese educational system lays emphasis on cooperative behavior, group discipline, and conformity to standards. It served the country well in producing the skilled industrial workforce that made Japan a global economic power in the 20th century. The success of the system is further reflected in the fact that the great majority of the Japanese people consider themselves middle class and see education as the road to prosperity for their children. In recent years, however, there has been considerable debate and conflicting proposals as to the direction the education system should take to respond to the challenges of the 21st century. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In 2002 a new curriculum was introduced that sought to shift the emphasis from “uniform and passive” to “independent and creative,” with action being taken to reduce classroom hours and to create a more relaxed “low pressure” education environment. Subsequent international comparisons, however, have shown a decline in the academic abilities of Japanese children, and this has led to calls for getting back to basics and increasing classroom hours in certain subjects.

“In 2006 the government passed the first ever revision to the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education. This revision included provisions calling for education to instill public spiritedness, respect for tradition and culture, and love of country. The curriculum guidelines were also revised in 2008 to enhance fundamental education by fostering basic knowledge and skills, and to expand class hours. The new curriculum guidelines will be introduced in the 2012 school year for elementary schools and in the 2013 school year for junior high schools.

After World War II, pre-war hypernationalism was replaced by post-war communism, with students often taking the lead. Describing this period, the American diplomat Edward Seidensticker wrote in his memoir, “The world was divided between good guys and bad guys. The former were called peaceful and socialist, and their headquarters were in Moscow. This was before the break between China and the Soviet Union. The latter were the capitalist warmongers, and their headquarters was in Washington D.C.”

Regulatory reforms implemented in 2000 permitted individuals without teaching credentials or work experience in education to be employed as school principals in public schools. This has enabled the skills of people with a wide range of private sector experience to be utilized in the public school system. Subsequent reforms have relaxed requirements for the establishment of private elementary and junior high schools, and have made it easier for graduates of international and ethnic high schools in Japan to take the entrance examinations of national universities. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Education and Family in Asia

There is a strong emphasis on education. Stanley Karnow wrote in Smithsonian magazine: "Like other Asians, who traditionally revere scholars, they value learning. They also see education as both the path to success and consistent with their sense of filial piety, the way to bring esteem to their family."

Education is seen as a family effort requiring a great deal of sacrifice, time and money. Parents watch over their children carefully and guide and direct them. At an early age children are taught to memorize their textbooks. By Kindergarten they are attending a wide range of music, art and calligraphy classes.

See Education Crazy Mothers, School Life

Confucianism, Education and Administration

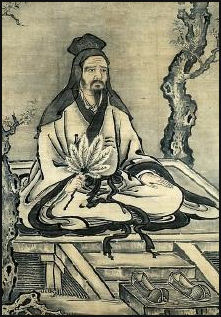

Confucius Japanese education is rooted in Confucianism. Confucianism has had an influence on Japanese education. Confucius is credited with organizing China's first educational system and setting up an efficient administration system, based on the careful selection of a bureaucracy that helped the emperor and other leaders rule. Members of the bureaucracy were trained in special schools and chosen for their jobs based on their the proficiency on a civil service exam that tested their knowledge of Confucian texts. Before Confucius's time the only schools in China were ones that taught archery.

Confucius regarded government and education as inseparable. Without good education, he reasoned, it was impossible to find leaders who possess the virtues to run a government. "What has one who is not able to govern himself, to do with governing others?" Confucius asked. Under Confucianism, teachers and scholars were regarded, like oldest males and fathers, as unquestioned authorities.

The basic principal behind Confucian education is that if you work hard, endure and suffer as a young person you will reap rewards later in life. The strategy of Confucian education, used in China for centuries, is to memorize the moral precepts in the hopes that they will rub off and improve the character of the person who memorizes them and makes him or her more moral. Teachers have traditionally been held in high esteem and their power and control has ben regarded as almost absolute.

Scholar-bureaucrats civil servants who ran the Chinese imperial government are known in the West as Mandarins (a term coined by the British). They were China's best and brightest, and served the emperor in the imperial court and as imperial magistrates and representatives in the hinterlands. Civil servants were recruited and promoted through a series of examinations. These tests were, theoretically at least, open to anybody and were responsible for a considerable degree pf social mobility. Success could bring privileged status and wealth to even the most humble born. Chinese Civil Service Exam was essentially a test of knowledge of Confucian texts. There were local, provincial and palace exams and they covered a number of topics, including poetry, philosophy, politics and ethics. Passing was said to be more difficult than getting into Harvard.

Japanese Concept of Education and Tests

According to a report by the U.S. Department of Education: "Japanese society is education-minded to an extraordinary degree. Success in formal education is considered largely synonymous with success in life and is, for most students, almost the only path to social and economic status." The cultural commitment to education can be traced back to Confucianism and Buddhism, both of which emphasize the importance of education.

The Western approach to talent is that some people have talent and some don't so that those with talent should be singled out and nurtured. The Eastern approach is that most people have average talent but given the proper training they can become skilled.

In Japan there are tests for everything. Many jobs requiring passing a test or and getting a license that requires passing a test. There are tests that designate those who pass them as official experts on Okinawa, Kyoto, the famous Chushingura (47 retainers) story, sochu liquor or Shoen Jump comic. In 2006, 7,000 people signed up to take a test on the kimono that addressed the garment’s history and how to wear it. In Hyogo, more than 500 people took a test of seafood called the Akashi Octopus Expert Certification Exam. A test of people’s knowledge of yokai, mythical Japanese monsters, is offered in Tokyo.

Learning and the Arts in Japan

19th century singing lesson Japanese artists have traditionally learned their crafts from senior family members or masters, whose wisdom has been regarded as beyond reproach and whose authority has not been questioned. Experimentation, improvisation and innovation have traditionally been taken as an insult to the master and have been undertaken only if a student becomes a master himself. The Socratic approach of learning through questioning is not encouraged. There is a risk of humiliating the master if he doesn't known the answer, plus asking a lot of questions is considered rude.

One Japanese American told the Boston Globe, "Modesty is considered a virtue in Japan in a way that isn't here and that's difficult for an artist or person who has excelled. To be a great performer or any kind of creative person, you have to express yourself and be as individualistic as you possibly can be. This is very difficult in that society."

Students are often like apprentices. During the early stages of their the learning process, they are often treating like servants. They spend their time cleaning and serving, doing tasks that have nothing to do with the craft, and supposed to take every opportunity they can to observe their master at work.

Later when the learning process begins, the student is student is expected observe and copy his master. Students are supposed to hang on every word their masters say and are supposed to do things exactly as the master and not ask any questions.

Japanese masters who have had foreign students often complain they ask question when they should be listening, pick and chose what they think is worthy to learn, get angry and hurt when they are corrected , and expect to be patted on the back when they do something good.

Classical Japanese music has a different philosophy than Western music. Form is often emphasized over content. In accordance with the concept of “hogaku”, an emphasis is placed on the position of the instruments, posture and handling the instrument with the understanding that if a musician can get these things right then good things will follow. Also part of this idea is that of you get the form right a spirit will enter you and give you the skill to play well.

The process of learning hogaku is called “keiko”, which essentially means exercise. Teachers spend a lot of time teaching form, sometimes with things like social etiquette, proper dressing and grooming and carrying oneself in a dignified manner included. Unlike Western musical students who are taught to practice and drill, Japanese musical students are taught to mimic their teachers and immerse themselves in the music.

Equality, Uniformity, Creativity and Education in Japan

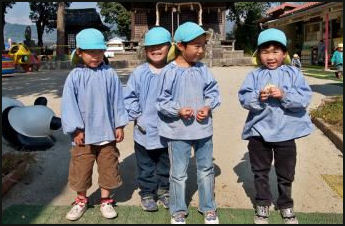

In school children are taught cooperative behavior and functioning in groups. There is an emphasis on uniformity in Japanese schools. The curriculum is the same for all students. Music teachers are told precisely which songs they have to teach in each grade. Children learn ideograms by rote at the same rate as other child in the same grade across the nation. There is generally no failing or advancing a grade, nor are there slow or fast groups within a given class. If students fall behind they must attend cram school classes to catch up.

"The Japanese," wrote Harvard educator Merry White, "have adopted a fiction that kids are innately equal and that you treat all children the same. They believe what matters is effort not some ceiling on ability...The Japanese simply do not want to recognize diversity. There's such an investment in homogeneity. They have phrases for it: 'We are all are one silk sheet.' 'The head that stick up above the others gets lopped off.' Japanese kids who go overseas with their parents come back marked as outsiders...There's a real problem for a Japanese kid who is different."

The Japanese education system is credited with creating one of the most literate and disciplined work forces in the world but criticized for discouraging diversity and creativity. White says that the idea that Japanese schools inhibit creativity is bunk . "If you read the creative writing of junior high school students, or look at their painting, it's fantastic," he said. "They all learn to read music and play two instruments. The Japanese believe that creativity comes with mastery, and mastery is what the schools can offer."

There has been some discussion of introducing a voucher system to improve education by introducing more competition. Under the system students and parents would receive government vouchers to be used for the school of the choice. Schools would be subsidized according to how many vouchers they have.

Some argue that there is too much emphasis on equality. Yasuchika Hasegawa, chairman of the Japan Association of Corporate Executives (Keizai Doyukai), told the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Japan now excessively seeks "equal results for all." I've heard about children crossing the finish line together hand in hand in races at an athletic meet. This is a bad example of the principle of equality. Equality of opportunity must be guaranteed, but there must be mostly unequal results in actuality...People achieve results according to their abilities, and elites selected in this way must be given a place to thoroughly compete with others. The Japanese seniority system does not suit the global age of great competition. Yasuchika Hasegawa, chairman of the Japan Association of Corporate Executives (Keizai Doyukai)

Women and Education in Japan

Japanese women are among the best educated in the world. In 2005, 42.5 percent of them had at least some post-secondary education.

The legal status of women before the 1947 Constitution was lower than that of men, and women were denied equal opportunity to education by law and custom.4 During the Edo Period (1603-1867), women, especially those of samurai status (less than 10 percent of population) were supposed to follow Confucianist teaching to obey their fathers, husbands, and sons. However, most women were farmers (80 percent of population) and worked together with men in the farms and fields. In the Edo period, girls began to attend temple schools (terakoya) with boys to learn reading, writing, and calculating. By the end of the Edo Period, the enrollment percentages in terakoya were 79 percent boys and 21 percent girls (Passin 1965:44). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Since the 1872 School Ordinance, primary school education was provided equally to girls and boys. By 1910, almost all boys and girls attended elementary schools. However, co-education ended after elementary school, and female students attended female-only middle schools and female-only post-secondary schools in the gender-segregated school system. Until the end of World War II, women were not allowed entrance into Imperial Universities except for To-hoku Imperial University, which was opened to women in 1913. ~

In the 1930s, about 20 percent of boys went up to five-year middle schools, the first step for higher education, while 17 percent of girls attended female middle schools to become “good wives and wise mothers” (Aramaki 2000:16). By 1937, there were 42 three-year private women’s colleges, six public colleges for women, and two national women’s higher normal schools (Fujimura-Fanselow and Imamura 1991:233). During this period, only 1 or 2 percent of women attended postsecondary schools. ~

The 1946 Constitution and 1947 Education Fundamental Law guaranteed equal rights to education for women. Furthermore, the human rights of women are protected by a series of international human rights treaties: the U.N. Human Rights Covenants in 1979; the U.N. Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1985; the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1994; and the domestic 1999 Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society. For equal rights of women in education, the U.N. Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women specifically mentions the elimination of prejudice based on “stereotyped roles for men and women” (Article 5), and the protection of the equal rights of men and women in education (Article 10). Article 10 stipulates “the elimination of any stereotyped concept of the roles of men and women at all levels and in all forms of education by encouraging coeducation and other types of education which will help to achieve this aim and, in particular, by the revision of textbooks and school programs and the adaptation of teaching methods.” ~

In practice, the gender gap is still evident in education and employment, though the discrepancy has been narrowing. Fewer female students than male students attend four-year colleges. Fewer female students major in science and engineering, which affects employment rates and wages. The “statistical discrimination” (Thurow 1975) against the employment of women, and their commitments of childbirth and childrearing also account for gender discrepancy in employment rates and wages. ~

Gender Roles in Japanese Schools

Schools still provide gender-specific education such as “boys-first” attendance sheets, and single-sex high schools. The “boys-first” attendance sheet contains the names of all male students first in an alphabetical order and then the names of all female students. Thus, male students are always called on first when a teacher checks the attendance. All classrooms and schools used “boys-first” attendance sheets before the 1983 nationwide movement for gender-neutral attendance sheets. The movement began when one elementary school teacher began using a gender-neutral attendance sheet in her classroom. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Feminist critics argued that “boys-first” attendance sheet implied the superiority of boys over girls. Many municipal boards of education decided to use a gender-neutral attendance sheet for all public schools under their jurisdiction. In 2000, 46.6 percent of elementary schools, 28.7 percent of middle schools, and 55.3 percent of high schools used gender-free attendance sheets (Nihon Fujin 2002:165). The 1999 survey of the JTU (Japan Teachers’ Union) found that 43.6 percent of schools used a gender-neutral attendance sheet but that there was a large regional discrepancy. Some regions have a very low usage of the gender-neutral sheets, such as 13.8 percent in Iwate Prefecture (AS Iwate April 15, 2000). It is easy to change the currently used “boys-first” attendance sheet into a gender-neutral attendance sheet. Therefore, there is no reason for schools to keep using “boys-first” attendance sheets. The gender-neutral attendance sheets should be used in all schools. ~

Some old public high schools and many private schools have kept single-sex education. As of 1997, 50.8 percent of private high schools and 4.3 percent of public high schools are single-sex (Kimura 1999:47). Private schools have the right to be sex-segregated, following their school policy. Though many feminists have questioned the existence of public single-sex schools, some studies from the U.S. have shown that female students in same-sex high schools tend to have higher self-esteem, and higher academic accomplishments in mathematics and science, and are less likely to seek gender-stereotyped jobs and careers than female students in co-education (Sadker and Sadker 1994:232). ~

The most obvious case of gender bias in school education was female-only home economics education courses in middle schools and high schools. Home economics (e.g., sewing, cooking, housekeeping, and childcare) classes had been assigned to only female students in middle and high schools until 1993 (for middle schools) and 1994 (for high schools). Schools reproduced traditional gender-roles of women as homemakers. Currently, more than 90 percent of families responded that women were in charge of cooking and doing laundry in their family in Japan, compared with three-fourths of American families, according to a 1992 survey (Bando- 1998:22). ~

Boys and girls in the fifth- and sixth-grades learned cooking, sewing, and handcrafting together in elementary schools, but by middle school, the students went to separate classrooms. Before 1989, male students went to take an “industrial arts” class while female students studied home economics. Male students learned home improvement skills such as carpentry from a male teacher, while female students learned sewing, cooking, and child care from a female teacher. In high schools, home economics classes were required only for female students until 1994. In my high school, male students were assigned physical education classes, while female students were required to take home economics classes. ~

The Association for the Promotion of Home Economics for Male and Female Students, formed by teachers, journalists, and citizen’s groups in 1974, lobbied for the abolition of gender-segregated home economics classes in cooperation with labor unions and educational organizations. After the ratification of the U.N. Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the implementation of the Equal Opportunity Employment Act of 1985, the MOE created gender-free home economics for middle and high schools in the 1989 Course of Study. ~

Since 1994, both male and female middle school students now take industrial arts and home economics classes, including woodcrafts and cooking. Since 1994, both male and female high school students are required to take home economics classes. Male students are also required to learn cooking, sewing and childcare in the formal school curriculum. Perhaps male students will learn to share housekeeping responsibilities in the future. ~

Formation of Gender Roles at Home and in School

Both parents and teachers tend to be less aggressive in encouraging female students into achieving higher educational goals, in contrast to male students, because of expected gender roles. Most people believe that women, unlike men, do not have to work to support their families once they marry. According to a 1999 survey of the parents of fourth to ninth graders, the majority of parents (69.3 percent) wanted their daughters to be “like girls” and their sons to be “like boys” (So-mucho- 2000b:123-124). Many parents expect their daughters to have a “woman-friendly” education such as junior college. Parents generally expect their sons more than their daughters to attend four-year colleges. According to a 2000 survey, 66.9 percent of parents of children ages 9-14 expected their son to go to a four-year college, while 44.7 percent of parents expected their daughter to go to a four-year college, and 17 percent of them wanted their daughters to go to a junior college (Naikakufu 2002:104). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

According to the 1995 Social Stratification and Social Mobility (SSM) survey, women who had high academic achievements in the ninth grade tended to attend institutions of higher education, regardless of their father’s occupations. The only exception can be found in women from blue-collar backgrounds. It is because it is far less expensive to attend local colleges. However, women in their 20s whose grades were average during ninth grade were 50 percent more likely to attend colleges if their fathers were in professional and managerial positions than those whose fathers were in clerical and sales positions (Iwamoto 2000:87). Many private colleges and junior colleges are not competitive. Therefore, female students who have average grades can still attend colleges. Those who have fathers in professional and managerial positions may also be more encouraged to attend colleges. ~

Furthermore, according to surveys taken in 1980 and 1982, parents tend to spend more on their sons for private educational institutions, such as private after-school classes (juku), private tutors, and correspondence courses than on their daughters (Stevenson and Baker 1992:1643-1655). However, in recent years more parents, especially mothers agree with gender-neutral education at home. According to a 1995 survey, only one-third of women between ages 25-44 agree that boys and girls should be raised differently, compared with more than half (53 percent) of the same age group of women who agreed with the statement in the 1985 survey (Ojima and Kondo- 2000:29-30). ~

In the United States, since the 1970s, education specialists found gender-specific “hidden curriculum” in classroom management, student guidance, and school events, through classroom observation and textbook analysis. Based on classroom observation, they argued that teachers in general expect male students to do better in class than female students, and that teachers interact with male students more than with female students in class. The analysis of textbooks and instructional materials confirms the lack of women’s contributions and the invisibility of females in curriculum materials (Sadker and Sadker 1994:55-65, 70-72). ~

Japanese feminist activists and educational specialists have followed the example of the United States, and began to analyze textbooks and classroom management. Textbooks, especially those on Japanese language arts, social science, and home economics often have many examples of stereotyped gender roles and sexism. An analysis of the 1991 elementary textbooks for 1992-1996 academic years found that the main characters in novels and important figures in history are overwhelmingly male. Traditional gender roles are strongly emphasized, such as the depiction of women as being kind and generous, while men are depicted as being decision-makers and breadwinners (Niju-ichiseiki 1994:22). ~

Gender Gap in Educational Achievement in Japan

Influenced by their teachers’ and parents’ views of gender roles, female students are more likely to attend less competitive academic high schools or commercial high schools rather than technical high schools. Almost half of male and female students went to college in 2003. One seventh (13.9 percent) of female students went to junior colleges. Therefore, one-third (34.4 percent) of female students, compared to slightly less than half of male students (47.8 percent) went to four-year colleges after high school. However, this gender gap is closing. In 1960, only 2.5 percent of women, compared to 13.7 percent of men, went to four-year colleges (Naikakufu 2004c). Junior colleges, 90 percent of whose students are female, have the image of “preparatory schools for good housewives.” Junior colleges teach home economics, humanities, education, social science, and public health, mostly for women. Most junior college graduates obtain clerical or sales jobs in private companies and work as “Office Ladies” before marriage or motherhood. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The gender gap in majors at universities and colleges affects employment and wages. Lifelong employment for college-educated women has been traditionally restricted to the professions of teaching and public service. An overwhelming majority of college-bound high school female students choose to major in traditionally female fields such as humanities, home economics, and social science rather than science and engineering. Only 7.5 percent of female students majored in science and engineering in 2000 (Table 3.3). However, compared to a decade ago, these numbers have increased. Because of a lack of background in science and engineering, many female college graduates have had a much harder time obtaining a job. After the development of micro-electrics and computer science, where working environments are friendlier to women than in heavy industry, more female students have majored in engineering and computer science. ~

Majors of College Students by Gender in 2000: Male students:Humanities—8.7 percent; Social Science—46.1 percent; Science— 4.2 percent; Engineering—27.0 percent; Education— 3.6 percent; Health Care—4.2 percent; Others—6.2 percent. Female students: Humanities—30.2 percent (36.3 percent in 1998); Social Science—29.3 percent (17.7 percent in 1998); Science— 2.4 percent; Engineering—5.1 percent (2.4 percent in 1988); 2.4 percent in 1988; Education— 8.9 percent; Health Care—8.5percent; Others—15.6 percent.

American Pedagogy Verus Japanese Pedagogy

Japanese primary and secondary schools have produced a workforce with solid knowledge and a strong work ethic. There are many reasons for this success: longer school days, a uniformly high standard of curriculum, excellent teachers, active parental involvement in education, and respect for education. During the 1980s and the early 1990s, foreign scholars and journalists praised Japanese education for producing an educated and industrious workforce for economic and technological success. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The Japanese primary and secondary school education has been successful in producing a generation with one of the highest level of academic achievement in mathematics and science in the world. In 1964, the first international study of achievement in mathematics for 13 year-olds and 18 year-olds discovered that Japanese students scored the highest. International studies of science achievement among 10 and 14 year-olds in 1970-1971, and those of mathematics achievements for 13-year-olds in the early 1980s show that Japanese students again scored highest (Lynn 1988:4, 15-16). ~

The 2003 survey by the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS 2003) found that Japanese eighth graders ranked fifth of 46 countries in mathematics and sixth in science, while American eighth graders ranked fifteenth in mathematics and ninth in science. Also, Japanese fourth graders came in third of 25 countries in mathematics and third in science while American fourth graders ranked twelfth in mathematics and sixth in science (AS December 15, 2004). In addition, Japan enjoys one of the highest literacy rates in the world. Almost 100 percent of children are enrolled in elementary school, and the illiteracy rate among children is almost zero. ~

However, Japanese people have a reputation for being less creative and individualistic because of the emphasis on memorization and rote learning in education. The current reform focuses on developing students’ creativity and individuality. Local control, elective courses, comprehensive high schools, volunteerism, and community involvement are key elements of American education. On the other hand, American schools concentrate on basic knowledge, demanding the curricula and testing that have been the foundation of Japanese education. ~

Concerned with the deterioration of academic performance, conservative educators gained prominence in the 1980s. The 1983 reform report, A Nation at Risk by the National Commission on Excellence in Education recommended a program of “New Basics,” a required core curriculum. The Commission criticized the extensive “cafeteria-style curriculum” in high schools as the main cause of declining academic achievement and SAT scores (NCEE 1983; Angus and Mirel 1999:2-3). More and more students have been taking academic courses since the reform. In 2000, 31 percent of students completed recommended core requirements: 4 units of English, 3 units of social science, 3 units of science, 3 units of mathematics, 2 units of foreign language, and 0.5 unit of computer science (NCES 2003a). ~

Standardized test scores have generally been used to measure academic achievement. Under the 1994 law, states are required to test students once during elementary school, middle school, and high school. In January 2002, President George W. Bush signed the “No Child Left Behind” Bill which requires annual state tests in reading and mathematics for every child in grades three through eight, starting in no later than the 2005-6 school year. Recently, some states and school districts have developed specific curricula which teachers are expected to follow in order to raise test scores, though critics point out “teaching to the test” undermines students’ creativity (TIME March 6, 2000). Teachers are being held responsible for their students’ performance. The teachers, principals, and administrators in California’s lower 50 percent of schools, who helped students raise their standardized test scores were eligible for large cash bonuses from the state’s testing-and-accountability programs (Los Angeles Times October 10, 2001). ~

In the United States, ability grouping starts in elementary school. Elementary schools have within-class ability grouping, advanced classes for gifted and talented children, and special education classes for children with learning disabilities. Middle and high schools usually use a tracking system, which distribute students among ability- or interest-based classes. Since the early 1970s, programs for gifted students have become popular in public schools, and 12 percent of students receive some kind of advanced instruction. In public schools, gifted students are invited to participate in special math, science, or arts classes. Some districts provide summer camps or after-school classes for gifted students. In California, 6.12 percent of students participate in these programs. Students who enroll in these programs often need to have an IQ of 120 or higher, but many programs accept students on the basis of teacher recommendations, academic records, interviews, or other tests (Los Angeles Times April 1, 2001). ~

In Japan, ability grouping and tracking in elementary and middle schools has been a taboo subject because of the egalitarian philosophy of education following World War II. However, during the 2002-3 school year, the MOE launched limited ability grouping for advanced students in elementary and middle schools. Upon entering high school, almost all Japanese 15-year-olds take entrance examinations that determine their placement in hierarchically ranked academic, vocational, or comprehensive high schools. ~

In the United States, the number of public school students diagnosed with learning disabilities (LD) had increased to six percent by 1998. The majority of LD children stay in special education throughout their school years, and may encounter discrimination in postsecondary education and employment. However, a survey showed that only 15 percent of LD students met the clinical definition of LD, and that most students diagnosed with LD lived in poverty, and scored low in cognitive development (Meyer, Harry and Sapon-Shevin 1997:337). The overrepresentation of minority and disadvantaged children indicates that the low scores on reading performance are caused not by learning disabilities, but by poverty, disadvantaged educational environments, and the lack of early education (Los Angeles Times December 12, 1999; Agbenyega and Jiggetts 1999). Early compensatory education for disadvantaged children, such as Head Start, helps these children avoid being labeled as LD. In Japan, the MOE plans to start similar special education for children diagnosed with learning disabilities. ~

In the United States, elementary schools do not have tracking systems, but many teachers frequently use differentiated instruction to meet the needs of all students in a classroom. It is believed that the students learn more successfully if they are taught according to their levels of readiness, interests, and learning profiles (Tomlinson 2000). In middle schools, ability grouping and tracking in reading, English, and mathematics classes is very common. According to a 1993 survey, 82 percent of middle schools used ability grouping to some extent, though 36 percent of schools reported that they might abandon ability grouping (Mills 1998). Black, Hispanic and Native American students and low-income students are overrepresented in the lower tracks. It is generally believed that tracking gives high-achieving students the challenge and stimulation that they need, while it stigmatizes low-achievers as slow learners, and relegates them to second-class status, with inferior instruction, less experienced or committed teachers, and lower expectations. ~

Tracking in middle schools has declined nationwide. Middle school educators have argued that the enriched curriculum, high-level thinking, and problem-solving techniques used in gifted classes would benefit all students (Tomlinson 1995a, 1995b). Public high schools usually have three tracks: academic, general, and vocational. In addition to their distribution requirements for graduation, students take classes according to their interests and academic goals. College-bound students may take more honor classes, or Advanced Placement classes; vocational students may take courses in typing and business. ~

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~; Education in Japan website educationinjapan.wordpress.com ; Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2014