REQUIREMENTS FOR A POLITICAL PARTY IN JAPAN

Murayama, Socialist Prime

Minister in the 1990s "Seito" is the Japanese word for political party, a group of people who share the same opinions about politics and pursue the same goals. "Yoken" means requirement. Any group that wants to be recognized as a political party must meet legally defined requirements, which are called "seito yoken." [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 6, 2012]

According to the Public Offices Election Law, which lays down a set of rules for the election of politicians, an organization that wants to be acknowledged as a political party must fulfill either of the following two conditions: A) Five or more House of Representatives or House of Councillors members must belong to the group; or B) The group must gain 2 percent or more of all votes cast in the most recent lower house or upper house election, except for votes declared invalid.

A group that has been recognized as a political party is eligible to field candidates in both the single-seat constituency and proportional representation categories in elections. It is also allowed to have its single-seat constituency race candidates appear on TV and radio broadcasts in which they can express their political views. Obviously, this can provide an advantage for the group as it conducts an election campaign.

Socialist Party and Communist Party in Japan

Social Democratic Party (SDP) grew out of the Japan Socialist Party, which for many years was the main opposition to the LDP. It briefly formed a Socialist government in 1947 and 1948, and again in 1994. It did poorly in the elections in 2003 and 2005.

The SDP has been accused by the LDP as being a bunch of loony leftists and criticized by leftists for being conservative. James Sterngold wrote in the New York Times, Socialists traditionally "saw themselves as the nations conscience, putting principal ahead of power as they fought for a pacifist foreign policy, a strong social welfare system and the closing of American bases here. The positions, however impractical, struck an emotional chord."

In the 2003 election the SDP lost two thirds of seats (from 18 to 6). Takado Doi , Japan’s most well-known female politician, lost in humiliating fashion to an LDP rookie but kept her seat through party representation.

The Japan Communist Party (JCP) was founded in 1922 and recognized after World War II. It abandoned its Marxist-Leninist doctrines in favor of social democracy in 1976. The Communists were at their peak in elections in October 1996, when Communist won 7.3 million votes (10 percent of all votes cast), beat the Socialists and increased their number of lower house seats from 15 to 26. Much of the credit for their success has been given to their charismatic leader, Kazou Shii, known as the "prince." The JCP has done progressively poorly in elections since 1996.

By one count there are 20,000 hardcore leftists in Japan. Leftist groups have traditionally supported North Korea and opposed U.S. military bases in Japan.

New Komeito, Soka Gakkai and Politics

New Komeito poster

The New Komeito (Clean Government Party) is the political arm of the Soka Gakkai (Value-creating Society), one of the largest religious sects in Japan with around 8 million members. Soka Gakkai, also known as Hito no Michi, is a form of Mahayana Buddhism and has links to the Nicherien sect of Buddhism. It followers believe that salvation and good luck can be attained by repeatedly chanting, "I take my refuge in the Lotus Sutra."

Komeito (Clean Government Party) has been a major force in Japanese politics for three decades. Founded in 1964, it was the third largest party in Japan in 1980, with 49 members. In 1995, it had 52 seats in the 511-member lower house of the Diet. (The lower house wields more power than the rubber-stamp upper house).

In 1995, Komeito merged with Shinshinto (New Frontier Party), the main opposition party. In a July 1995 election, Soka Gakkai accounted for half of Shinshinto's 12.5 million votes. Before the alliance with Shinshinto, Soka Gakkai maintained links with a corrupt faction in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LPD).

Komeito is a well organized political machine supported by a massive army of volunteer canvassers. It legislators claim they are not followers of Soka Gakkai (Komeito and Soka Gakkai formally broke formal ties in 1970) but nearly all them were practitioners of the religion before they were elected.

In late 1990s Komeito morphed into the New Komeito Party, which has been a coalition partner of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party of Japan for more than a decade. Prime Ministers Obuchi, Mori, Kouzimi, Abe, Fukuda and Aso all formed coalition governments with the New Komeito Party.

In October 2006,Akihiro Ota was selected as the new leader of the New Komeito party. He was 62 and served five terms in the lower house and is the former head of Soka Gakkai’s youth department.

New Komeito lost seats in the 2007 upper house election. It had hoped to win 13 seats but only won nine, Party members blamed the LDP for their loss.

Soka Gakkai isn't the only religion involved in politics. Other Buddhist sects have political wings and legislators who support their causes in return for financial support. The Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult reportedly decided to launch the sarin gas subway attack after it failed to do well in local elections.

See Separate Article: SOKA GAKKAI factsanddetails.com

Local Parties and New Parties in Japan

Regional parties roughly can be divided into two types: those run by local government heads such as Genzei Nippon and Osaka Ishin no Kai and those that are not. One member of the former category is Saitama Kaientai (group supporting reform in Saitama), which was formed by five municipal government heads in Saitama Prefecture.

Clashes with municipal assemblies are often behind the formation of such parties — leaders who have their proposals rejected by the assemblies attempt to get them to do what they want by throwing their support behind assembly candidates who will back their policies once elected. The LDP still retains an overwhelming majority among regional assembly members.

In April 2010, prominent members of the LDP — former Finance Minister Kaoru Yosano and former Trade Minister Takeo Hiranuma and three other prominent lawmakers broke away from the LDP and formed a new party — the Sunrise Party. Tokyo mayor Shinatro Ishihara supported the new party but didn’t join it. Ishihara wanted to call the party Tachiagare Nippon, which literally means “Stand Up, Japan .” Not long after that former Health, labor and Welfare Minister Yoichi Masuzoe quit the LDP and formed a new party. In March 2010, Kunio Hatoyama — the brother of then Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama — resigned from the LDP, expressing an interest in forming his own party.”

Nationalists and Right Wing Groups in Japan

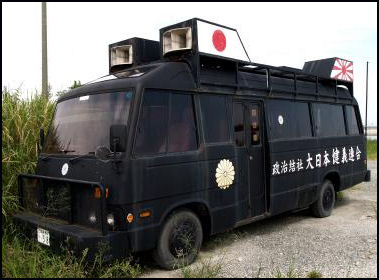

right wing super van According to a government report in 1995, there are 980 rightist groups in Japan with 120,000 members, of whom 23,000 are active. Right wing groups are strong supporters of Japanese nationalist causes and have been at the forefront of Japan's refusal to apologize for World War II aggression. They have also been at the center of disputes over rose-tinted interpretations of Japanese history and hostilities between Japan and China, Taiwan, and Korea over possessions of tiny islands in the Japan and South China seas. Some have blame the United States for the Japanese recession in the 1990s and have called for a revival of emperor worship.

Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “The traditional far right, which has roots going back to at least the 1930s rise of militarism in Japan, is now a tacitly accepted part of the conservative political establishment here. Sociologists describe them as serving as a sort of unofficial mechanism for enforcing conformity in postwar Japan, singling out Japanese who were seen as straying too far to the left, or other groups that anger them, such as embassies of countries with whom Japan has territorial disputes.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 28, 2010]

Issuikai is a well-known far-right group with 100 members and a fleet of sound trucks. In August 2010, a visit partly organized by Issuikai, far-right French nationalist politician, Jean-Marie Le Pen, and British nationalist leader Adam Walker visited Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo the day before the anniversary of the end of World War II to pay respect to those who died in the war they said. The visit was put together by the International Conference of Patriotic Organizations, which brought together right-wing parties from eight European countries with members of a far-right Japanese group called Issuikai.

Many right-wing nationalists are supporters of the Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), Japan’s largest nationalist organization. It has conservative members in the Diet that are mostly from the LDP. It reject Japanese pacificism, embraces the Imperial system and defends Japan’s actions in it wars in Asia. It has also been active in keeping the North Korea abduction issue alive, wants Japan to possess nuclear weapons and has been critical of the United States for bringing pacifism to Japan.

Traditional ultranationalist groups have been shrinking. One members of the movement told the New York Times the number of old-style rightists has fallen to about 12,000, one-tenth the size of their 1960s’ peak.Right wing groups are increasingly finding new members among young “freeters” who don’t have regular jobs, are cast adrift and find some solace in patriotism and nationalism.

Yasukuni Shrine and Nationalism in Japan

Yasukuni Shrine was built in 1869 under the Emperor Meiji. It memorializes almost 2.5 million Japanese, including women and children, who died in wars since 1868. The overwhelming majority — about 2.1 million — died in World War II. What makes the shrine so controversial is the fact that it honors hundreds of convicted war criminals, including 14 so-called Class A criminals, such as executed war-time leader Hideki Tojo, the prime minister who authorized the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Their spirits have been "enshrined" there since 1960s and 70s. Shrine organizers stress that many thousands of civilians are honored. China and South Korea however see the shrine as glorification of Japanese atrocities. The 14 "Class A" war criminals were the men who ordered and oversaw Japan’s brutal war in China and South East Asia, which left millions dead and included widespread massacres of civilians, rape used routinely as a weapon and the use chemical and biological weapons by the Japanese against civilians. [Source: BBC, Washington Post]

“It’s only natural to extend sincere condolences to people who dedicated their lives to their country,” Keiji Furuya, chairman of the National Public Safety Commission, said after visiting the shrine in 2014. “I paid a visit to pray for peace.” Yoshitaka Shindo, minister of internal affairs and the grandson of Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander during the battle of Iwo Jima, said his visit was “a private act and won’t cause any concern...I came here to pray with respects for the souls of the valuable lives perished in the war so that a war will never happen again.” [Source: Anna Fifield, Washington Post, August 15, 2014]

Right Wing Extremists in Japan and Their Tactics

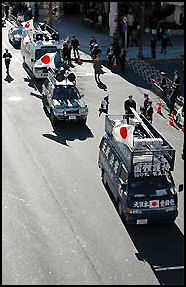

older, smaller right wing van Right-wing extremist have been described as semi-fascists and petty-criminals. They harass critics, enemies and government agencies they don't like with buses and vans mounted with loudspeakers that blast out extremist diatribes. Describing the barrage from one these vans Howard French wrote in the New York Times, “The noise sneaks on you from afar, starting with the low beat of a bass drum whose rumble recalls the boots of soldiers on the march....Next comes the unmistakable strains of martial music. What follows is a performance of emperor worship and militaristic propaganda that is as deafening as a Marilyn Manson concert.”

Many say the tactics employed by right wing groups are nothing but a form of extortion. For $1,000 a day right-wing ultra-nationalists can be hired to harass companies or individuals by setting up of their loudspeaker trucks and denouncing them with loudspeaker barrages. They are sometimes hired by the political elite to harass their opponents. Right wing groups have also been known to pull their vans outside businesses and blast out messages criticizing the management until they are paid off.

Right-wing ultra-nationalists sometimes have ties with the yakuza and often get away with harassing people with little interference from the police. Some right-wing groups have friendly relations with police. There have been cases where their vans and trucks with ear-splitting speakers have even been given police escorts.

A survey in 2009 found that 141 government offices had been harassed by gangster or rightist groups in the previous year.

Right Wing Extremist Violence in Japan

Right wing extremists were involved in political violence and assassinations. In October 1960, Inejiro Asanuma, chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, was assassinated by a member of a right wing group while giving a speech.

Violence by right wing groups in the 1980s and 1990s included the attack on Tsuruo Yamaguchi, secretary general of the Social Democratic Party, in Shiga Prefecture in May 1989; the shooting attack of LDP Vice President Shin Kanemaru by a shooter who missed in Tochigi Prefecture in March 1992.

In 1990, the mayor of Nagasaki was shot in the back by a right wing extremist apparently in retaliation for breaking a long-standing taboo by publicly suggesting in 1988 that the late Emperor Hirohito was responsible for Japan's participation in World War II.

In May 1994, a rightist tried to shoot former prime minister Morihiro Hosokawa, who admitted in the Diet that Japan fought a war of aggression in World War II. Shots were fired at the former prime minister at a Tokyo hotel but missed. After Hosokawa apologized for Japan's war record in 1993, one rightist L.D.P. member told the Diet that anyone who made that kind of remark should be killed.

Rightist have also attacked and taken hostages at the liberal Asahi Shimbun newspaper and attempted to shoot deputy prime minister Shin Kanemaru after he made overtures to North Korea. One right-wing extremist held a Ministry of Finance official hostage and said he wouldn't be freed until the government deregulated the financial industry. Another extremist rammed his car into the gate of the South Korean embassy and set the car on fire while giving out literature condemning South Korea and the Japan Broadcasting Corp. (NHK). The man was apparently upset over the territorial dispute between Japan and South Korea over the Tokd-Takeshima islands.

Right Wing Extremist Violence in the 2000s

In August 2006 the home of general Koichi Kato in Yamagata Prefecture was burned down by an arsonist whe followed up his attack with a suicide attempt. Kato criticized Koizumi’s decision to visit Yasukuni shrine and opposed Japan’s nationalist policies on Asian issues. In the mid-2000s ultra-rightist also firebombed the house the Fuji Xerox CEO, who had also criticized Koizumi’s decision to visit Yasukuni shrine.

In October 2002, lawmaker Koki Ishii of the Democratic Party of Japan was stabbed to death outside his house in Tokyo. The attacker was a rightist leader who had demanded a meeting with Ishii.

A deputy foreign mister criticized as being soft on North Korea discovered a time bomb in his house in 2003. Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara said in speech he “had it coming.” Other have been threatened for endorsing female succession to the imperial throne.

Right Wing Sword Group Violence

Right-wing sword groups, going by several names including Token Tomo no Kai (sword friendship society), Kenkoku Giyugun (nation-building volunteer corps) and Seibatsi-ta (traitor punishment corps) were involved on a number of violent incidents in the early 2000s, including the shooting of a teacher’s union official in Hiroshima, the planting of a bomb in the home of a foreign minister, and attacks on members of the Aum Supreme Truth cult and pro-North Korean organizations.

Sword groups have described themselves as “modern-day samurai.” They have expressed anti-American and anti-Communist views on their websites and traveled to islands whose ownership is disputed by Japan, Taiwan and China. A leader of one group said “I will devote myself to my believed nation” and wrote “we shall march into battle under the banner of anti-communism, anti-Americanism and ant-socialism.”

Japan’s New Internet-Organized Ultranationalist Groups

Since the late 2000s a new type of ultranationalist group has emerged. Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “The groups are openly anti-foreign in their message, and unafraid to win attention by holding unruly street demonstrations. Since first appearing in 2009, their protests have been directed at Japan’s half million ethnic Koreans as well as Chinese and other Asian workers, Christian churchgoers and even Westerners in Halloween costumes. In the latter case, a few dozen angrily shouting demonstrators followed around revelers waving placards that said, “This is not a white country.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 28, 2010]

“Local news media have dubbed these groups the Net far right, because they are loosely organized via the Internet, and gather together only for demonstrations. At other times, they are a virtual community that maintains its own Web sites to announce the times and places of protests, swap information and post video recordings of their demonstrations. While these groups remain a small if noisy fringe element here, they have won growing attention as an alarming side effect of Japan’s long economic and political decline. Most of their members appear to be young men, many of whom hold the low-paying part-time or contract jobs that have proliferated in Japan in recent years.”

right wing activists “Though some here compare these groups to neo-Nazis, sociologists say that they are different because they lack an aggressive ideology of racial supremacy, and have so far been careful to draw the line at violence,” Fackler wrote. “There have been no reports of injuries, or violence beyond pushing and shouting. Rather, the Net right’s main purpose seems to be venting frustration, both about Japan’s diminished stature and in their own personal economic difficulties.

“These are men who feel disenfranchised in their own society,” Kensuke Suzuki, a sociology professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, told the New York Times. “They are looking for someone to blame, and foreigners are the most obvious target.” They are also different from Japan’s existing ultranationalist groups, which are a common sight even today in Tokyo, wearing paramilitary uniforms and riding around in ominous black trucks with loudspeakers that blare martial music.

Members of these old-line rightist groups have been quick to distance themselves from the Net right, which they dismiss as amateurish rabble-rousers, Fackler wrote. “These new groups are not patriots but attention-seekers,” Kunio Suzuki, a senior adviser of the Issuikai, a well-known far-right group, told the New York Times. But in a sign of changing times here, Mr. Suzuki also admitted that the Net right has grown at a time when traditional ultranationalist groups like his own have been shrinking.

See Racism

Image Sources: 1) 2) Wikipedia, 3) 4) 5) 7) 10) Kantei, Office of Japanese Prime Minister site, 6) 12) Japan Zone, 8), 9) Minshuto 11) Ray Kinnane, Posters, right wing, Japan Photo japan-photo.de ;

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016