GOVERNMENT SYMBOLS IN JAPAN

World-War-II-era

Imperial Japanese

Navy flag Japan does not have an official head of state, and, for a long time it didn’t have an official flag, or official national anthem. One of the reasons for this is that country's unofficial head of state (the Emperor), flag and anthem still are associated with Japanese aggression during World War II and not recognized by the constitution or the international community.

Japan’s national flag is the Hinomaru, and its national anthem is “Kimigayo.” In August 1999, a law was passed that made the Hinomaru flag, and the Kimigayo national anthem (See Below) legal symbols of the nation for the first time. Supporters for the law, mainly from members of the LDP, argued that there was nothing intrinsically militarist about the flag and the anthem, so why not make them official symbols. Plus, they were important in instilling national pride.

Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi said, the “Kimigayo” "is understood as a prayer for peace and longstanding prosperity of the nation, with the emperor personifying the integration of people and country."

Liberals opposed the law, claiming there should be some kind of public referendum on the issue. After the decision was announced rightists rode through the streets shouting nationalist slogans and leftist protested outside Parliament.

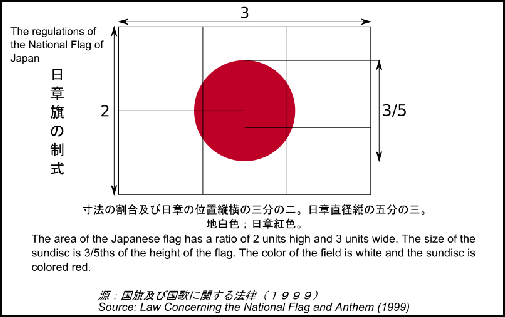

Hinomaru Flag

The Hinomaru (Rising Sun) flag is the name of the flag with the red ball (representing the sun) against a white background. This flag is not to be confused with the Japanese navy flag which shows a red sun with 16 wavy red bands radiating from it. This flag is associated most with World War II. The Hinomaru name comes from the Japanese word “hinomaru”, which literally means ‘sun circle.” The red circle symbolizes the sun. The vertical-to-horizontal ratio of the flag is set at 2:3; the disc is placed at the exact center; and the diameter of the disc is equal to three-fifths of the vertical measurement.

Flags showing the rising sun were used by some of the noted clan heads in ancient days. A record of these flags appears in annals written about 600 years ago. When the ban against building large vessels was lifted-after the advent of Commodore Perry's squadron in 1853-1854- the necessity arose to distinguish Japanese ships in foreign commerce, and the flag, as it now appears, was suggested as a national ensign by Lord Nariakira Shimasu, head to the Satsuma clan. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“By official proclamation issued in January, 1870, the standard form and size of the flag were fixed in a rectangular proportion of 3 for the length and 2 for the width, with the diameter of the sun three-fifths of the width, placed in the center of the flag. The material, whether silk, cotton or muslin, was not stipulated. This ordinance was made to clarify the confusion then existing relative to the flag. The flag-staff universally used is of bamboo, painted black every few inches. It is capped with a golden ball.

“The first display of the sun flag as the symbol of the nation was on the occasion of the trip to the United States, in 1860, of the first embassy every sent abroad by the government. It numbered 70 in all. The Powhattan, a steamship of the U.S. navy, was placed at the disposal of the Shogunate for this purpose. The ship flew the American flag at the stern, and the Japanese flag at the bow. In a national rite the flag was first used in Yokohama on the occasion of the opening of the first railway in Japan, by Emperor Meiji, on Sept. 17, 1982. The people of Yokohama, and those who lived along the rail line, hit upon the happy idea of displaying sun flags in front of every house in honor of the Emperor, and in celebration of the occasion.

Many Japanese symbols and names are linked with sun. There is the rising sun flag, of course. Nihon and Nippon — names for Japan — both mean "Sun Origin." Many large Japanese companies also have the sun in their names. They include Hitachi ("Sunrise"), Asahi ("Rising Sun") and Nissan ("Sun Origin Industries").

Before the Hinomaru flag was adopted as the official nation flag in 1999 it had no legal status even though it was flown over the prime minister's office, many government buildings and Japanese embassies abroad and was raised for medal winning athletes at the Olympics and other international sports events.

The Hinomaru flag was created in the 1600s by the Tokugawa shoganate to use aboard ships. The use of the sun as a symbol of Japan dates back centuries before that and the flag's design has it roots in the 13th century. In 1870 Hinomaru flag was designated as the official Japanese flag for seagoing ships.

History of the National Flag of Japan

It is not certain just when the sun-circle symbol was first used on flags and banners. However, in the 12th century “samurai “warriors (bushi) “appeared, and during the struggle for power between the Minamoto and Taira clans, “bushi “were fond of drawing sun circles on folding fans known as “gunsen”. In the Warring States period of the 15th and 16th centuries, when various military figures vied for spheres of influence, “hinomaru “were widely displayed as military insignia. One screen painting depicting the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 shows a military force whose many banners all share the “hinomaru “motif. Although a red circle on a white background was the most common, there were also examples of gold circles on a deep blue background. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The use of a “hinomaru “as the symbol of the country as a whole dates from its use, by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the late 16th century and Tokugawa Ieyasu in the early 17th century, on the flags of trading ships sent abroad. A screen with scenes from the 17thcentury city of Edo (present-day Tokyo) shows a “hinomaru “flag being used as the symbol of a ship carrying the shogun. During the period of “sakoku”, or “national seclusion” (1639-1854), trade and other relations with all foreign countries except China, Korea, and Holland were prohibited, but when the Tokugawa shogunate began to trade with other countries (including the United States and Russia) after 1854, Japanese trading ships again began to use a “hinomaru “flag. The Tokugawa shogunate in 1854 accepted a proposal by Shimazu Nariakira of the Satsuma domain, and it was decided that Japanese ships, so as not to be mistaken for foreign vessels, would use a “”hinomaru “banner with a white background.” A “hinomaru “flag was displayed on the “Kanrinmaru”, the official ship bearing Japanese officials sent to the United States in 1860. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In 1868, the Meiji government was established after the Tokugawa family lost political power. According to Proclamation No. 57 issued by the Grand Council of State (Dajokan) on January 27, 1870, the Hinomaru was officially made the flag of Japan for use on commercial vessels. The Hinomaru was first used on the grounds of government buildings in 1872, the year before the lunar calendar was officially replaced by the solar calendar. At that time many ordinary families and non-governmental establishments also expressed the desire to display the Hinomaru on national holidays. In subsequent years, a number of notifications and documents were publicly issued which reinforced the Hinomaru’s status as the flag symbolizing Japan.

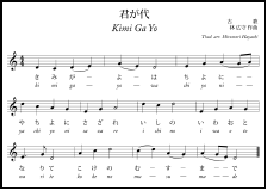

Kimigayo, the Japanese National Anthem

The Japanese national anthem, “Kimigayo”, is sung at official events, and played at medal award ceremonies at the Olympics and the closing of sumo tournaments, but for a long time was considered to controversial to designate as a national anthem. The “Kimigayo” is an ode to the Emperor. It is more of a hymn than a song. It has been described as melancholy, even depressing, Many young people don’t understand the meaning of the ancient words.

The words of Japan’s national anthem, “Kimigayo,” are taken from an ancient poem.According to the Guinness Book of Records, “Kimigayo” is the world's oldest national anthem. The words date back to the ninth century and are believed to have been derived from a poem celebrating longevity from in a collection of classical waka poems. The music was written in 1881 by Horomi Hayashi (the original music written in 1870 by British military bandmaster John Fenton was thrown out). In 1893 the Kimigayo was declared the official ceremonial song sung at primary schools.

“Kimigayo” is also one of the world's shortest national anthems. It only has four lines. It goes:

“Thousands of years io happy reign be thine

Rule on, my lord, til what are pebbles now,

By age united, to mighty rocks shall grow

Whose venerable sides the moss doth line”.

The exact meaning of “Kimigayo” is not clear. "”Kimi”" means "you," which is widely regarded as a reference to "Your Majesty" (the Emperor). "”Yo”" means "age" or "era." The most widely excepted titles for the song are "Your Majesty's Era," or "The Reign of Our Emperor." Some liberals believe "yo" means nation. Thus the name of song would be "Emperor's Nation." Others say that "kimi" refers too the Emperor as a symbol of the country. If so the title could be translated as "The Reign of Our Emperor But Only as Symbol of the People."

History of the “Kimigayo”

It is not known who first wrote the words of the anthem. Although they are found in a poem contained in two anthologies of Japanese 31-syllable “waka”, namely, the 10thcentury “Kokin wakashu “and the 11th-century “Wakan roeishu”, the name of the poem’s author is unknown. From very early times, the poem was recited to commemorate auspicious occasions and at banquets celebrating important events. The words were often put to music with melodies typical of such vocal styles as “yokyoku “(sung portions of Noh performances), “kouta “(popular songs with shamisen accompaniment), “joruri “(dramatic narrative chanting with “shamisen “accompaniment), “saireika “(festival songs), and “biwauta “(songs with “biwa “accompaniment). The words were also used in fairy tales and other stories and even appeared in the Edo period popular fiction known as “ukiyo-zoshi “and in collections of humorous “kyoka “(mad verse). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The government presented its interpretation of the meaning of the anthem “Kimigayo” in the Diet during the deliberation of a bill to codify the country’s national flag and anthem. At the plenary session of the House of Representatives of the Diet held on June 29, 1999, Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo explained as follows: “”Kimi”” in “Kimigayo”, under the current Constitution of Japan, indicates the Emperor, who is the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power; “Kimigayo” as a whole depicts the state of being of our country, which has the Emperor — deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power — as the symbol of itself and of the unity of the people; and it is appropriate to interpret the words of the anthem as praying for the lasting prosperity and peace of our country.”

Music of “Kimigayo”

When the Meiji period began in 1868 and Japan made its start as a modern nation, there was not yet anything called a “national anthem.” In 1869 the British military band instructor John William Fenton, who was then working in Yokohama, learned that Japan lacked a national anthem and told the members of Japan’s military band about the British national anthem “God Save the King.” Fenton emphasized the necessity of a national anthem and proposed that he would compose the music if someone would provide the words. The band members, after consulting with their director, requested Artillery Captain Oyama Iwao (1842-1916) from present-day Kagoshima Prefecture, who was well versed in Japanese and Chinese history and literature, to select appropriate words for such an anthem. (Oyama later became army minister and a field marshal.) [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Fenton put his own music to the “Kimigayo” words selected by Oyama from a “biwauta “titled “Horaisan”, and the first “Kimigayo” anthem was the result. The melody was, however, completely different from the one known today. It was performed, with the accompaniment of brass instruments, during an army parade in 1870, but it was later considered to be lacking in solemnity, and it was agreed that a revision was needed. In 1876, Nakamura Suketsune, the director of the Naval Band, submitted to the Navy Ministry a proposal for changing the music, and on the basis of his proposal it was decided that the new melody should reflect the style used in musical chants performed at the imperial court. In July 1880, four persons were named to a committee to revise the music. They were Naval Band director Nakamura Suketsune; Army Band director Yotsumoto Yoshitoyo; the court director of “gagaku “(Japanese court music) performances, Hayashi Hiromori; and a German instructor under contract with the navy, Franz Eckert.

“Finally a melody produced by Hayashi Hiromori was selected on the basis of the traditional scale used in “gagaku”. Eckert made a four-part vocal arrangement, and the new national anthem was first performed in the imperial palace on the Meiji Emperor’s birthday, November 3, 1880. This was the beginning of the “Kimigayo” national anthem we know today. Today the Hinomaru and “Kimigayo” are displayed and performed during ceremonies on national holidays, during other public observances on auspicious occasions, and in ceremonies to welcome state guests from abroad. In addition, many Japanese citizens display the Hinomaru outside their front doors on national holidays. The music of “Kimigayo” is performed also at non-official events, such as international sports events where Japanese teams are represented. At tournaments of “sumo”, which is considered by many to be Japan’s national sport, the national anthem is commonly performed prior to the award ceremony. Acknowledging that the wide usage of the Hinomaru and “Kimigayo” has taken hold as customary law, the government, on the eve of the 21st century, deemed it appropriate to give them a clear basis in written law. A bill to codify the Hinomaru and “Kimigayo” as the national flag and anthem was submitted to the Diet in June 1999. The Law Concerning the National Flag and National Anthem was enacted by the Diet on August 9, 1999.

Controversy Over the Hinomaru Flag and Kimigayo

Kimigayo played at

a volleyball game Critics of the use of the Hinomaru flag and Kimigayo claim they are associated as much with the horrors of World War II as the swastika and “Deutschland Uber Allies” are with Nazi Germany. During World War II, people in lands occupied by the Japanese were forced to sing the “Kimigayo” at school and pledge their loyalty to the Hinomaru flag.

Raising the Honimaru flag was banned from the end of World War II to 1949. No such restrictions were made on the “Kimgayo”. In 1948, a law was passed that no longer obliged schools to play the song during school ceremonies. Polls have consistently showed there is more support for the flag than the Kimigayo.

Controversy Over Hinomaru and Kimigayo at Schools

In 1989, the Education Ministry called for the Hinomaru flag and Kimigayo to be used in school graduation ceremonies. The left-leaning Japan Teacher Union opposed the measure, suggesting the song “Midori Sanga” ("Green Mountains and Rivers") as a replacement.

in October 2003, the Tokyo government under Governor Shintaro Ishihara made raising the Hinomaru flag and playing the Kimigayo anthem compulsory at gradation and enrollment ceremonies in public school and stated that failing to comply is a punishable offense. According to the law the Japanese flag must be in tandem with the Tokyo flag and, after an official cries out ‘singing of the national anthem,” students and teacher stand up face the flag and sing, with officials taking down the names of those who refuse to comply.

One teacher who refused to sing the national anthem was required to undergo “special retraining” and write a self examination. Another who refused to stand up and sing was fired and had to take up work as a carpenter to make ends meet. Conservatives argued that such strict measures were needed to counterbalance “decades of leftist lectures by liberal teachers and efforts to denigrate the flag by placing it next to toilets.” Even the Emperor spoke out on the issue, saying “its not desirable to do it by force.”

In September 2006, a Tokyo District Court ruled teachers are not required to sing the national anthem. In March 2009, a court rejected a lawsuit filed by teachers punished for refusing to stand and sing the national anthem, ruling the Tokyo Board of Education acted within it constitutional boundaries.

In May 2011, the Japanese Supreme Court ruled it was constitutional for a school principal to make teachers stand and sing “ Kimigayo “,"the national anthem, together in front of the national flag at a graduation ceremony. The ruling was made on an appeal by a former teacher at a Tokyo metropolitan government-run high school whom the Tokyo government refused to reemploy because he had disobeyed the principal's instruction to stand and sing the anthem. The former teacher had demanded compensation. He said he opposed singing the anthem, as a matter of conscience. He argued that by ordering teachers to stand and sing, the principal had infringed on their constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of thought and conscience.

In March 2011, a Tokyo high court overturned a lower court ruling and annulled disciplinary action taken against 168 school teachers and school staff who refused to stand when the “ Kimigayo “ was played. Two months earlier the court said the Tokyo metropolitan was within constitutional bonds to require teachers to stand and sing the national anthem.

The punishments for teachers in Tokyo begins with a warning and advances to pay cuts, suspension from work, and finally dismissal. Other municipalities that have rules requiring teachers to show respect to the “ Kimigayo “ and the “ Hinomaru “, the Japanese flag, include Osaka, Hiroshima and Kanagawa Prefectures.

One teacher who refused to stand told the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t harbor ill feelings for the anthem. This shouldn’t be allowed in a democracy.”

In 1996, the Japanese Supreme Court ruled in favor of protecting a Jehovah's Witness student's right to freedom of religion at a public high school. The judge ruled it was wrong to force an act that was against an individual's religion, and that the school needed to explore alternatives so rights wouldn't be infringed. [Source: Los Angeles Times]

Suicide Over the Kimigayo

Many liberal schools, particularly in the Hiroshima area, have refused to fly the Hinomaru flag or have the Kimigayo sung. Those in Hiroshima are opposed to the symbols because of their links to the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. In 1999, 194 public school teachers there were punished because they refused to stand as the “Kimigayo” was sung at graduation and entrance ceremonies.

In February 1999, a school principal in Hiroshima prefecture hanged himself after he was unable to resolve a dispute between the local school board who ordered that the Kimigayo be used in school ceremonies and teachers who refused to obey the order.

A note in the principal's car read" "I don't know what is right. Maybe I'm not capable of management. I cant find a way out." A few hours before his death he said, "Whatever I say [the teachers] don't listen. If I say one thing they respond with 20...They said if I kept insisting in the anthem, they wouldn't even agree to have the flag."

In June 1999, a middle school principal was stabbed in the chest and back three times with a fruit knife and seriously injured by a 29-year-old man, and former student at the school, who promoted the use of the Hinomaru flag.

National Holidays

Winter and Spring: New Year's Day (“Ganjitsu”) January 1 Celebrates the beginning of the new year. Coming-of-Age Day (“Seijin no Hi”) 2nd Monday in January This holiday honors young people who have reached the age of 20. National Foundation Day (“Kenkoku Kinen no Hi”) February 11 This holiday commemorates the start of the reign of Japan’s legendary first emperor, Jimmu. Vernal Equinox Day (“Shunbun no Hi”) around March 21 This is a day for family reunions and visits to family graves. Showa Day (“Showa no Hi”) April 29 This is a day to reflect upon the turbulent days and subsequent recovery of the Showa period (1926-89) and to think about the future of Japan. It is the birthday of the late Emperor Showa. Constitution Day (“Kenpo Kinenbi”) May3 This holiday commemorates the entering into effect of the Constitution of Japan in 1947. Greenery Day (“Midori no Hi”) May 4 This is a day to enjoy nature, to be thankful for nature’s blessings, and to nurture a rich spirit. Children's Day (“Kodomo no Hi”) May5 This is a day to wish for the health and happiness of children. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

‘summer and Autumn: Marine Day (“Umi no Hi”) 3rd Monday in July This is a day to thank the sea for its blessings. Respect-for-the-Aged Day (“Keiro no Hi”) 3rd Monday in September This is a day to show respect to the elderly. Autumnal Equinox Day (“Shubun no Hi”) around September 23 This is a day for family reunions and visits to family graves. Sports Day (“Taiiku no Hi “) 2nd Monday in October Established in 1966 in commemoration of the opening of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, this is a day to promote health and physical fitness. Culture Day (“Bunka no Hi”) November 3 This is a day on which the ideals of peace and freedom expressed in Japan’s Constitution (promulgated on November 3, 1946) are fostered through cultural activities. Labor Thanksgiving Day (“Kinro Kansha no Hi”) November 23 This is a day to show appreciation for labor and to celebrate a good harvest. Emperor's Birthday (“Tenno Tanjobi”) December 23 On this day, in 1933, Emperor Akihito was born,

Japanese Government and the Emperor

Imperial throne in the

House of Representatives The Japanese constitution, instituted in May 1947, after World War II, demoted the Emperor from a "living god" to a "symbol of the state” and a “unifier of the people.” The Emperor was stripped of his political and diplomatic power and was recast as a symbol of new democratic, postwar Japan. Although Hirohito renounced his divinity he was careful not to deny that he was a descendent of the Sun Goddess. Without that he would have no claim on the throne.

The Emperor has no powers related to the government. Most parliamentary systems are formally headed by a king or queen. At the end of the World War II, it was decided that it would inappropriate to name the Emperor as the head of state in the new Constitution and the position was left vacant.

The legal status of the Emperor is defined by the Japanese constitution in Article 1—“The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power” and Article 4—“The Emperor shall perform only such acts in matters of state as are provided for in this Constitution and he shall not have power related to government.”

One Japanese official told the New York Times, "We don't really have a head of state. I mean there's the Emperor, of course, but there's no head of state. When we need a head of state we bring the Emperor out. So he's head of state when we need a host for a state visit, But he's not really head of state."

The prime minister takes office when he is handed his commission by the Emperor.

Image Sources: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Wikipedia, 6), 7) Shugin House of Representatives site , 8) Japan Zone, 9) Ray Kinnane, local government, Aomori Prefecture . Tokyo offices, Japan-Photo.de

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012