JAPANESE VIDEO GAME PLAYERS

game center players Japanese kids play a lot of video games. According to one survey 90 percent of kids age 10 to 14 own video games. “Otaku” (computer-game obsessed boys) seem to as passionate about video games, computer software and the Internet as Japanese girls are with fashion and pop singers. During one video game event at the Tokyo Dome riot police had to be called in after a crowd of 50,000 fans, most of them children, got out of control as they tried to get their hands on limited-edition cards from the hit game “Legend of the Duelist”.

Especially with the growing popularity of hand-held devices, video gamers are growing younger and younger. It is not uncommon to see nursery-school-age children sitting alone playing a game even when they are in park. Among primary schoolers, it is not uncommon to see a whole group of boys gathered around a single hand-held devise. Kids that aren’t into games are ostracized by other kids or at least feel left out.

One survey conducted by Goo Research via an Internet site popular with primary-school-age kids found that 80 percent of respondents regularly play vide games and 30 percent of boys said they played for more than three hours a day. According to the survey 15 percent of 3½ year olds, 28 percent of 4½ year olds and 51 percent of 5½ year olds played video games and only 35 percent of families had special rules to limit the time spent playing video games.

Japanese parents have the same fears about violent video games, such as “Street Fighter”, as American parents do. Several violent crimes have been linked to violent video games, including the beheading of an 11-year-old boy by a middle school student in Kobe in 1997.

The Japanese anime director Manoru Oshii is a big video and computer game fan. He told the Daily Yomiuri, “I’ve got a lot of spare time, so when I start a game like “Dragon Quest”, I don’t stop until I am finished. I don’t go to work. I get a bunch of food ready and eat while I’m playing. In Japanese we call it “taking a trip.” When I “take a trip,” I don’t go to work, I don’t go out. When a phone call comes in, I say, “I’m on a trip.”...But I return to society. The reason I come back is because the game ends. Games have an end, like movies do. But reality is never ending. There’s no choice but to come back to reality.”

Hardcore gamers in Japan can purchase a battery-powered vibrator that pulses at 30 times a second and pushes a game’s shoot button faster than any human can.

Effects of Video Games

Video games, computers and television have been blamed for the deteriorating eyesight of children. Parents and researchers worry most that excessive game playing prevents kids from developing social and communication skills and personal relationships.

A number of extreme cases of game playing have been reported. One kindergartner wet his pants because he was so consumed in a game and refused to go the bathroom. A primary school student continued playing with his handheld device even when kicking a ball around.

But statistics seem indicate that excessive gaming is less a problem than it used to be or that people are just getting kids playing games. The number of parents in Japan of 6-year-old who said their children played video games often decreased from 24.2 percent in 1995 to 20.2 percent in 2000 to 15.1 percent in 2005. Over the same period parents said their children played more outside and were more likely to amuse themselves with puzzles and card games.

Cultural Differences and Video Games

Video games themselves are different in Japan than they are elsewhere. In the Japanese version of a violent a character shot in the head may have brain matter spill out the head but the stays on the body whereas in the United States the head explodes.

When Sony Computer Entertainment (SCE) makes games it makes different versions for different markets around the world. The Japanese version of character in “Ratchet and Clank”, for example, has very large eyebrows. A spokesman with SCE told the Daily Yomiuri, “We just change the eyebrows, we made them thicker to skew it for a younger audience. If you look at “Koro Koro” [a popular Japanese children’s comic] characters, they have huge thick eyebrows which look ridiculous to adults but kids love them.”

On characters made for the game “Hot Shot Golf” in the United States, the SCE spokesman said, “They were completely redesigned because there is a gap in the understanding of the cultures. The Japanese characters are cartoony, but the U.S. characters are: ole “fat, old guy,” “pretty Texas gal,” and “baldy.” They are little more exposed, more on the strong side and easier to understand. A little more like “The Simpsons”.”

Portable games are popular in Japan because many Japanese spend a lot of time in trains whereas American spend their time in cars.

Otaku

”Otaku” describes a subculture of young, male geeks who lose themselves in a hermetic world of manga comic books and video games. In the past it was a derogatory term used to describe men who were obsessed with computers and hung out at game arcades and in the manga section of bookstores and had some issues that developed out of their passions.

Cyberpunk writer William Gibson defined otaku as a being “pathological-techno-fetishist-with-social-deficit...the information age’s embodiment of a connoisseur.” They embrace what Peter Schjedahl of The New Yorker called a bizarre mix of “apocalyptic violence, saccharin cuteness (“kawaii”), resurgent nationalism, and variously perverse sex.”

Otaku when roughly translated means “hey sir.” Otaku tend to fall into three different groups based on their obsession: 1) games and computers; 2) anime and manga: and 3) pop idols. There is some overlapping between the groups.

Otaku are seen as “anemic, inward-looking, vaguely autistic.” They prefer “things to people” and virtual worlds to real worlds. Etienne Barral, a French journalist who studied them, wrote: "They know the difference between the real and virtual worlds, but they would rather be in the virtual world."

Moe

an otaku

Otaku have their own expressions and slang. “Moe” (pronounced “moeh” and literally meaning “budding”) describes an overpowering love or fetish towards manga- or anime-related cuteness. Otaku expert Kanta Ishido described “moe” as “the sensation of being blissfully overwhelmed by cuteness or attractiveness.”

“Moe” is used in expressions such as “”Suzumiya Haruhi moe”,” a strong special feeling for the high school heroine of “Suzumiya Haruhi no Yuutsu”, a popular anime based on a novel for teenagers; “”Seira-fuku mie” — meaning a passion for sailor-style schoolgirl uniforms; and “meganekko moe” — describing a fascination for girls wearing eyeglasses. “Moe” is seen as a word used by an otaku to express his emotions for objects of his desires. If they see something that gets their emotions going they exclaim “Moehhh!” as a kind of release.

Otaku Activities

Akira Fujitake, a communications professor at Gakushuin University told the Japan Times, "Despite their inner loneliness, Japanese youth don't want to be bothered by others. They like such devises as mobile phones, PCs, TVs and comic because they are free to access or shun them whenever they like."

Otaku specialist Makoto Fukuda wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “There is a tradition in Japan’s otaku culture that even such things as trains or computer operating systems can be changed into cute characters in a way that turns inanimate subjects into characters meant to inspire a 'moe' response.”

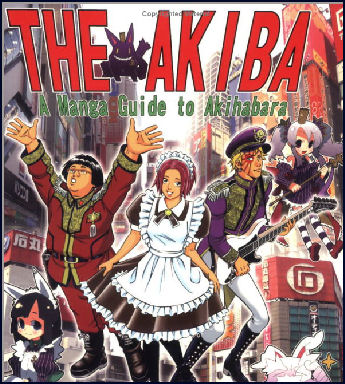

Akihabara, a district in Tokyo, is ground zero for otaku culture. It is chock-a-block wit, sidewalk cosplay displays, small but influential, back-alley anime and manga stores and maid cafes. Within a several block area there are over 80 maid cafes. Akihabara got its start as a center of black market activities after World War II. In the 1950s and 60s it was known as the place to buy radios and appliance. In the 1990s it became known for personal computers Over the years a number of shops that specialized in video and computer games and anime-related products opened up and these have attracted otaku.

On Sundays and holidays some of the streets are closed to traffic. In recent years these areas have attracted “cosplay” performers — people who dress up like manga and anime characters and put on street performances. Some regard the performances as a nuisance because they disrupt the flow of shoppers and there has been some effort to control them. One woman was arrested for putting on a show that climaxed with exposing her underwear.

Some otaku are geeky juvenile delinquents. They are notorious for engaging on shoplifting, petty crime and small time arson and occasionally violent crimes with knives. When the term “otaku” was first used it had very negative implications. Tsutomu Miyazaki — a psychopathic killer who killed four children and cannibalized two of them and left an ear in box at the house of one of his victims — was described as a otaku after police found a lot of manga and anime in his apartment

Online Gaming Addiction in Japan

Hiroyuki Doi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Addiction to online social gaming has grown into a serious problem among young people, with the numbers seeking medical treatment soaring. Clinics have received calls for help from people saying, "I can't stop playing online games even though I try," and "I can't stop spending all my money on games." One clinic has even set up an outpatient division specializing in online game addiction. [Source: Hiroyuki Doi, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 17, 2012]

A 19-year-old vocational school student recalled how one morning, he woke up at 6 a.m. on a sofa, still clutching his mobile phone. "Damn it! I was probably asleep for two hours," he said. Then he leaped up from the sofa and began fiddling with the phone again. Sometimes he was so preoccupied with the games that he forgot to sleep, he said.

It all began with games on his mobile phone during his first year of middle school. Initially he was killing time during his school commute, but then his lifestyle started to change. Such online games are in theory free of charge, but extras priced from 100 yen to 1,000 yen enable players to increase the physical strength or offensive capabilities of their characters. He said it made him feel good when "buddies" he knew through social gaming sites gave him praise such as, "You're so powerful.”

After entering high school, he began pouring about 80,000 yen a month, including earnings from a part-time job, into games. When he received 100,000 yen in New Year's gifts, he spent it all in just 10 days. His parents discovered his addiction when a bill for 50,000 yen in arrears was mailed to their home. By then, he had already spent more than 1 million yen. He was always late to school because he hadn't gotten enough sleep. His weight had dropped by several kilograms.

One winter, when he was a second-year high school student, his family took him to a private counseling center. Though he stopped playing games for a period, he became addicted again to other kinds of online games after enrolling in vocational school last spring. His voice was uneasy: "I've reached the very end. What happens if I die like this?" Yet he has been unable to stop playing the new online game. "I have no hopes for my future. But in the world of online games, my character is continually growing and developing, and I feel a sense of achievement that I never feel in the real world," he said.

The Consumer Affairs Agency began to regulate online social gaming in May 2012. A senior agency official said, "With the proliferation of smartphones, circumstances have changed to allow people to immerse themselves in online games around the clock, even while they are out or in bed.”

Treating Online Gaming Addiction in Japan

Hiroyuki Doi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Futoko Shien Center, a Nagoya-based association offering counseling services for truants, said it had received 327 individual requests for consultation for online game addiction from the beginning of this year to July. Zenkoku Web Counseling Kyogikai, a nationwide organization providing counseling services for Internet-related issues, said it had received about 150 similar requests for counseling over the past three years. [Source: Hiroyuki Doi, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 17, 2012]

Best known for treating alcohol addiction, Kurihama Medical and Addiction Center in Kanagawa Prefecture set up the nation's first outpatient division specializing in Internet-related addiction in July last year. Since then, 85 patients have been treated. The center said more than 70 percent were middle and high school students, mostly males.

Some major online game site operators have introduced usage limits. For example, in April, GREE Inc. and DeNA Co. began prohibiting users under 15 from accruing bills exceeding 5,000 yen a month. However, they have not created any time-based usage limits. The titles in question are online social games in which multiple users play simultaneously via the Internet. Users can exchange messages online to chat or to team up to fight enemies. Those whose school or work lives have been devastated by addiction to online gaming are known as "netoge haijin" (online game wrecks).

Kompu Gacha Social Games

In 2012, Kompu Gacha social games were in the news in Japan. According to the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Answer: Social games involve a system in which players exchange information with others on the Internet, using cell phones or smartphones. Players cooperate or compete in online games. The increase in social games began about three years ago and several corporations operate such games. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 29, 2012]

Some games have been criticized as children have spent too much money on them. Players do not have to pay to play, but they have the option to buy "aitemu," or virtual weapons and other items for improving their game performance, later receiving a bill for their purchases. Some parents have paid hundreds of thousands of yen to settle bills for items their children purchased in the month.

Many of these games are called "kompu gacha” in Japan. "Kompu gacha" is a system where items are purchased using a lottery called "gacha." If players successfully obtain a certain number of required virtual items in what is called "kompurito" (complete), they are awarded better virtual prizes. For example, if a player has obtained three out of four items for a kompurito set, he or she may continue buying items until getting the last piece. Such gimmicks are legally banned as they unfairly take advantage of people's tendency toward compulsive buying behavior. The government recently said the kompu gacha system is potentially illegal. This has made six major social game operators decide to get rid of the system.

Gacha games were first seen as a strong revenue source supporting the rapid expansion of the market. But there were some people, even among game developers, who questioned the use of sales methods that capitalized on users' gambling spirit. A 30-year-old male programmer who administers an online adventure game at an SNS game development company in Minato Ward, Tokyo, said he reponded to the crackdown on kompu gatch games by making it easier for players to win the last in a series of cards they need to collect. "Whether it's a good game depends on how much you can make a player buy virtual items," the man said. "The key is making 'haijin kakinsha' players use the game."[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 15, 2012]

Haijin and kakinsha mean wreck and someone who spends money, respectively, and haijin kakinsha is a derogatory term for an obsessed game player who spends thousands of yen or more a month. "It's our goal to make more than 10 percent of all gamers spend money," the man said. "It's important to keep their spending within certain bounds, since they may not come back to the game if we squeeze too much out of them." Players' spending status is constantly monitored by an in-house computer, and relevant data is sent to developers through e-mail, sometimes as often as once an hour. When the amount of money spent for a particular item or the number of players is too small, developers change the program immediately. They have sometimes reduced the price of a virtual item to 100 yen from 300 yen in a campaign. "It's all about figures," the man said.

So far kompu gacha games are the only type determined by the agency to be illegal for using the "cards combination" sales method. But there also are similar online games like "tema gacha" (theme gacha), in which players win further rare virtual items if they succeed in collecting a line of items based on a certain theme. There are also "bingo gacha" games, in which players win rare virtual items if they succeed in having all the numbers displayed in a certain line like a bingo game.

Kompu Gacha Addicts and Game Companies Like Gree

popular with otaku Describing a typical Kompiwrote in the A Tokyo female employee, 27, said once people start spending money to collect rare virtual items, they become unable to quit since owning a rare item carries a kind of status. "In the end I was playing out of pride," she said. At the invitation of a friend, the woman started playing a mobile phone game in April 2010 in which a player collects virtual treasure items in collaboration with other players. She was initially able to collect items free of charge, but needed to spend money to win a rare item. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 29, 2012]

Lured by advertising pitches like, "You can play a game 11 times for 3,000 yen if you pay a lump sum, although it usually costs 300 yen per game," or "This is the only time you can win this rare item," she got absorbed into the game. She said it took only about a minute to play 3,000 yen worth of the game. Flooded with new sales messages, she ultimately spent nearly 500,000 yen. According to a survey conducted by research company Neo Marketing Inc. earlier this month, 43 percent of 500 SNS game users bought such virtual game items, and 2.4 percent spent more than 10,000 yen. One player spent more than 200,000 yen in a month.

In August 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Gree Inc. President Yoshikazu Tanaka says the mobile game provider is suffering the effects of losing its lucrative "kompu gacha" (complete gacha) service. While it is difficult to analyze the loss in detail, "we have been struggling to cope, causing a delay in new game development," Tanaka said at a press conference. [Source: Jiji Press, August 16, 2012]

The company ended the service in May after the Consumer Affairs Agency decided such services are illegal due to their resemblance to gambling. Gree posted a group operating profit of 82.73 billion yen on sales of 158.23 billion yen for the business year that ended in June. Both its operating profit and sales jumped about 2.5-fold from the previous year. But the firm suffered term-on-term falls in sales and profit in the April-June quarter. For fiscal 2012 , it now projects an operating profit growth between minus 10.6 percent and plus 1.5 percent, which would be the first annual profit decline since it went public.

In January 2013, The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Major online social game provider Gree Inc. charged some minors fees in excess of its upper limits on gaming charges due to a flaw in its system, it has been found. A total of 733 minors were overcharged a total of 28.11 million yen, but although the company discovered the mistake in September, it did not make it public. Gree planned to make an apology as early as Monday and refund the excess charges in full. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 8, 2013]

Gree has come under fire for high charges to minors, leading the company to set a monthly upper limit of 5,000 yen for users aged 15 or younger and 10,000 yen for users aged from 16 to 19 since April 2012. However, cell phone users who pay by credit card were not covered by the charge limits. According to an official at the company, 733 minors aged from 10 to 19 used online games in excess of the upper limits. More than 30 users were charged over 100,000 yen a month, the official said. Gree said it noticed the mistake through an in-house investigation in September and fixed the system. But the company did not make the situation public or refund the charges, reasoning that "the number of affected people is small.”

Image Sources: 1) 3), 9), 15) xorsyst blog 2) 10), Japan Visitors 4) 7) Hector Garcia, 5) 8) Japan Zone, 11), 12) Mushi King official site 13) 14) Love and Berry official site

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013