JAPANESE WOMEN’S OLYMPIC WRESTLING

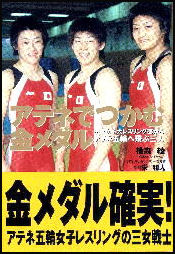

Japan arguably has the best women’s wrestlers in the world. At the 2004 Olympics, Japanese women medaled in all four of the women’s weight divisions. They won two gold medals and one silver medal and one bronze medal.

Japan arguably has the best women’s wrestlers in the world. At the 2004 Olympics, Japanese women medaled in all four of the women’s weight divisions. They won two gold medals and one silver medal and one bronze medal.

The medalists included the sisters Kaori Icho, who won a gold medal in the 63-kilogram division, and her led sister Chiharu who won a silver medal in the 48 kilogram class. Kyoko Hamaguchi, one of the most famous wrestlers in Japan, won a bronze in the 72 kilogram division. Saori Yoshida won the other gold. All four of the Japanese women were world champions coming into the Olympics.

Hamaguchi won the last of her five world tittles in 2003. She was coached by her father, who was a famous professional wrestler known as “Animal” Hamaguchi. Hamaguchi and her father are fixtures of Japanese television. She only managed to get a bronze in 2004 partly because she was screwed by a scoring error. She also won a bronze medal in the 72-kilogram division at the Olympics in Beijing in 2008. At age 30 she was happy with her achievement. In 2004 she was very disappointed.

Hitomi Sakamoto was another fine wrestler. She never made it the Olympics but won her sixth world title in October 2008 in the 51 kilogram class and retired . She was deprived of an Olympics spot in 2004 by knee surgery and in 2008 by an altering of the weight classes that worked to her disadvantage. Her sister Makiko is also a world class wrestler.

In September 2011, Hitomi Obara (formally known by her maiden name Hitomi Sakamoto) won her 8th world championship, successfully defending her 48-kilogram crown in Istanbul.

Japanese Wrestling at the 2012 Olympics in London

The national wrestling team for the London Olympics, which won four gold medals and two bronze medals in the Games, was named winner of the Japan Grand Prix at the 62nd Japan Sports Awards. Established by The Yomiuri Shimbun, the awards are given every year to the most prominent athletes and teams in the world of sports. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 15, 2012]

Japan worked to strengthen female wrestlers early, anticipating the event would become an official Olympic event. The effort has resulted in winning medals in all four divisions in both Athens and Beijing.

Japan's won its first World Cup wrestling title in six years in May 2012 in Tokyo on the eve of the London Summer Olympics. The win was tempered by Yoshida's shocking 2-1 (1-2, 2-0, 3-0) loss in the 55-kilogram class, just the second international defeat of her career and one that raises concerns with just two months to go to the London Olympics. [Source: Ken Marantz, Daily Yomiuri, May 28, 2012]

Japan, which ended China's five-year reign with a 5-2 victory in the final preliminary group match, had already clinched the title over Russia before Yoshida, a two-time Olympic and nine-time world champion, took the mat. "Japan won the title, so I'm happy about that," said Yoshida, whose tears never stopped through the medal ceremony and while talking with press. "Individually, I had that match in the final. As the team leader, it was a disgrace.

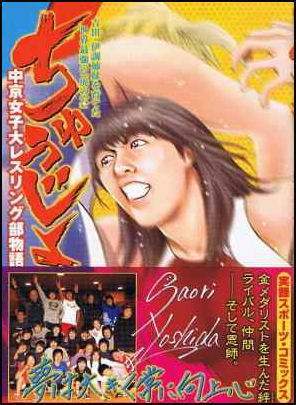

Saori Yoshida

Yoshida manga Saori Yoshida is Japan’s best wrestler. She won a gold medals in the 55-kilogram division at the Olympics in Beijing in 2008 and Athens in 2004. She won 119 straight matches and won six straight world titles. In 2007 she won the Grand Prix in Japan — the equivalent of being names sports person of the year.

Yoshida wins points with powerful take downs and often pins her opponents. She trained under her father, a national wrestling champion, who relentlessly worked on her tackling skills starting at age three Her streak of 119 victories came to an end in January 2008 when she lost 2-0 to American Marcie Van Dusem in Taiyian, China It was the first time she lost since December 2001 and her first loss ever to a non-Japanese.

Yoshida won a gold medal in 2008 by pinning Xu Li of China with 43 second left on the clock in the final. On the medal stand she burst in tears, feeling that she finally vindicated herself for her loss in January. “I’m really recovered. What happened to me in January really affected me. For a half year I’ve carried that tough memory with me.” In her four matches in Beijing she lost only two points. On her strategy in Beijing she said, “I stayed aggressive and I’m happy that on each of my tackles today, I wasn’t turned over.”

Saori Yoshida’s father Eikatsu Yoshida was selected to coach the women’s wrestling team in preparation for the 2012 Olympics in London. In 1973 he won the All-Japan wrestling title and played a prominent role in his daughter’s success.

In October 2012, Saori Yoshida's record of 13 global wrestling titles was recognized as a world’s best by the Guinness World Records. Yoshida, who earned both her third Olympic and 10th world gold medals in the women's 55-kilogram division in 2011, year, received a certificate from Guinness editor-in-chief Craig Glenday in a ceremony in Nagoya. "Even I'm amazed by the record," Yoshida said. At that time Yoshida said her next goal is to become Japan's first-ever four-time Olympic champion, which she aims to do at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Games.[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 16, 2012]

Yoshida was named sportsperson of the year in 2010 and 2007. As of 2010 she had won eight consecutive world championships and two straight Olympics gold medals. In September 2011, Saori Yoshida won her 9th straight world championship in the 55-kilogram division in Istanbul.

Saori Yoshida Earns Third Straight Olympic Gold in London

Saori Yoshida earned the third gold medal of her Olympic career, winning a decision by points against Canada's Tonya Lynn Verbeek in the 55-kilogram freestyle wrestling division. Yoshida defended her title from the 2004 Athens Games and Beijing four years ago. With the addition of her nine world titles, she matched the record of 12 world-level championships held by Russian Alexander Karelin, a three-time Olympic gold winner in Greco-Roman wrestling. "I have taken 12 gold medals and every single medal is important to me. But the medal I got at London 2012 is very important," said Yoshida. [Source: Fox Sports Network, August 9, 2012]

A major hurdle was the semifinals where Saori faced Valeria Zholobova, the Russian wrestler who stopped Saori's 58-match winning streak at a World Cup competition held in Tokyo in May 2012. The 29-year-old Saori did not give up a point to her opponent, however, and cruised into the final, where she defeated Canada's Tonya Verbeek, a long-time rival.

Yoshida carried the Japanese flag when Team Japan marched into the main stadium as the 95th delegation among the 204 countries in the London Olympics' opening ceremony. Seventy-six athletes and related officials followed Yoshida, bearing the Japanese flag and leading Team Japan, "The flag, as I expected, was heavy," Yoshida, 29, said of the seven kilogram flag and pole."I felt the weight of the Olympics through the flag. I feel an even stronger desire to go for gold in my matches."

Keiichi Kojima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Yoshida stood tall as she carried the flag, walking with dignity. She told reporters afterward: "It feels wonderful to be given the best role of this occasion...The Olympics gave the flag [I carried] special importance. I was honored to be entrusted with this incredible role on the greatest of stages." [Source: Keiichi Kojima, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 29, 2012]

Yoshida did not shy from carrying the flag despite rumors of a jinx against female flag-bearers. None of the previous nine women who carried the flag for Japan won a gold medal. Yoshida laughed off the superstition. "I'll break that jinx," she said. Hearing her comment, Yoshida's coach and team director Kazuhito Sakae reportedly expressed relief that "tough-talking Saori is back." Yoshida expressed enthusiasm to make this Olympics one to remember. "Japan has had so much dark news lately, including the Great East Japan Earthquake. We want to cheer people up through sports," she said. The fierce competitor writes "one who is pursing her dream" when asked for her autograph. "I want to show the Japanese people how wonderful it is to work toward a dream," she said.

Yoshida’s Wresting Career

Keiichi Kojima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Yoshida's strength lies in her aggressiveness during matches. Her father, Eikatsu Yoshida, a former wrestler himself, began teaching her on a mat at the family's home from the age of 3, emphasizing high-speed takedowns. [Source: Keiichi Kojima, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 29, 2012]

Yoshida won her first gold medal in the 2004 Athens Olympics, where women's wrestling debuted as an Olympic sport, and repeated in 2008 in Beijing. Shortly after her triumph in Beijing, she vowed to win her third gold at the London Olympics. However, she suffered a major setback in May when she was upset by a lower-ranked Russian wrestler at an international competition in Tokyo. The loss broke a streak of 58 consecutive wins that had begun in January 2008. After the match, Yoshida collapsed into tears of shock.

After the loss, her father told her, "Remember the wrestling techniques I taught you so many years ago." The comment reminded her of her daily practice of takedowns and strengthened her resolve to compete aggressively.

Yoshida's Dad a Big Help

Nasuka Yamamoto wrote in the Asahi Shimbun, “Thinking this might be the last Olympics he could share with his daughter, Eikatsu Yoshida decided to go to London to be in her corner. Saori Yoshida did not disappoint her 60-year-old father as she won her third straight Olympic gold medal in the women's wrestling 55-kilogram category. Eikatsu carefully watched his daughter and called out with advice to her whenever he felt she was becoming too tense or nervous. [Source: Nasuka Yamamoto, Asahi Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

Eikatsu has always been in Saori's corner, having taught her the basics at a small school he set up in Mie Prefecture. Eikatsu is a former national champion, and he taught children wrestling at the gym set up at his home. Saori began wrestling at age 3 and she was so fast people complained they could not take good photos of her during matches.

Her favorite tackling technique was personally instilled in her by Eikatsu. He taught his daughter to polish her tackling technique because of his own bitter experience. He lost by a tackle in the final selection process to pick the Japanese team for the Montreal Olympics in 1976. Ever since, he has told his daughter that the only way to win was to always be on the offensive.

Even after winning two Olympic gold medals, Saori would still return to her father's gym when she felt she was in a slight slump. Watching the children spar with one another while some were crying brought back memories of her own start in the sport, according to her mother, Yukiyo, who said, "That is the best medicine for her." While many wrestling fans in Japan were confident Saori would win her third consecutive Olympic gold medal, Eikatsu was more cautious.

"Her speed has fallen compared to when she was at her peak," he said. Eikatsu's concerns became reality at the World Cup team competition in May. After having her win streak stopped by Zholobova, Saori could not stop crying even as she climbed the victory podium as Japan claimed its team gold medal. "By losing, she can understand various things," Eikatsu said. "She has become stronger because she also knows the fear of losing."

Eikatsu realizes the enormous pressure his daughter had to endure as the "face of Japan." "There would be nothing better than having my daughter win the gold while I serve as her coach," he said.

Shocking Defeat Halts Yoshida's Winning Streak at 58

Ken Marantz wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, in 2008 Saori Yoshida was dealt a severe shock ahead of the Beijing Olympics when she lost at the Women's World Cup to an opponent who relied solely on defensive techniques. Fast forward to the event at Tokyo's Yoyogi No. 2 Gym, where lightning struck Yoshida again at the hands of an unheralded Russian teenager named Valeria Zholobova. Japan's first World Cup title in six years was tempered by Yoshida's shocking 2-1 (1-2, 2-0, 3-0) loss in the 55-kilogram class, just the second international defeat of her career and one that raises concerns with just two months to go to the London Olympics. [Source: Ken Marantz, Daily Yomiuri, May 28, 2012]

"Japan won the title, so I'm happy about that," said Yoshida, whose tears never stopped through the medal ceremony and while talking with press. "Individually, I had that match in the final. As the team leader, it was a disgrace. "Losing in the World Cup makes me wonder about London." In another setback, Kyoko Hamaguchi was pinned by world junior champion Natalia Vorobeva in the final match of the day at 72 kg, leaving Japan with a 5-2 victory but a 2-2 mark in the four Olympic weight classes.

The mood was light when Yoshida took the first period from Zholobova. But in each of the next two periods, Zholobova stopped a Yoshida tackle attempt and launched a hip throw that, while not toppling the Japanese over, caused her to step out of bounds for a crucial first point. Zholobova's other points came on an unsuccessful replay challenge by Japan and a desperation throw attempt by Yoshida that landed her on her back.

The loss was eerily reminiscent of the one at the 2008 World Cup to American Marcie Van Dusen, who attempted no tackles of her own but twice used Yoshida's momentum with a counter that threw her onto her back. That ended a 119-match winning streak for Yoshida, who had since won 58 in a row. Yoshida emerged from that loss stronger and more determined, resulting in a second Olympic gold in Beijing.

To be fair to Yoshida, the 19-year-old Zholobova is a natural 59-kg wrestler who was inserted into the lineup at 55 kgs because of a two-kilogram allowance in effect for the World Cup. "My opponent knew I was going to tackle, so it was difficult to get inside," the 29-year-old Yoshida said. "Even when I got in deep, she was so strong. I have to do more to finish the move."

Yoshida has been experimenting with putting more distance between her and her opponent when she starts an attack, but has had problems with reacting to the opponent's initial counter. It cropped up at last year's world championships, where she struggled to narrowly defeat Canada's Tonya Verbeek, and again at the All-Japan tournament in December, where rising star Kanako Murata stretched her to the limit. "I'm thinking too much about being countered," Yoshida said. "I want to go for a tackle, but I hold back and put on a mental brake. I'm starting to lack courage to shoot. "I need to work things out both technically and mentally in the two months before London."

Icho Sisters

The sisters Kaori and Chiharu Icho are two women wrestlers who have done well in the Olympics and world wrestling championships. Kaori won gold medals in the 63 kilogram division at the 2004 Olympics in Athens and the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and kilogram Chiaharu took silvers in the 48 kilogram division in 2004 and 2008. As of 2008, Kaori was world champion five straight times and Chiharu was world champions three times. Kaori has not lost since March 2003,

The sisters Kaori and Chiharu Icho are two women wrestlers who have done well in the Olympics and world wrestling championships. Kaori won gold medals in the 63 kilogram division at the 2004 Olympics in Athens and the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and kilogram Chiaharu took silvers in the 48 kilogram division in 2004 and 2008. As of 2008, Kaori was world champion five straight times and Chiharu was world champions three times. Kaori has not lost since March 2003,

Chiharu is the older sister and Kaori is the younger one. The sisters grow up in a wrestling hotbed of Hichinohe, Aomori Prefecture and followed an older brother into the sport. Both sisters won gold medals in the world wrestling championship in Baku Azerbaijan in 2007. Kaori won a gold medal at the 2004 Olympics in Athens at age of 23 in the 63 kilogram. Chiaharu list on the finals and took a silver in the 48 kilogram division.

Kaori won a gold medal in he 63-kilogram division at the Olympics in Beijing in 2008, defeating Alena Kartashova of Russia in the final. Both sisters wrestled on the same day. Kaori was broken up seeing her sister lose in the final match shortly before she was suppose to wrestle but she overcame her let down and an injured right foot to secure the gold. She had injured her foot in a grueling semifinal match which she won with a last second reversal. After that match she could hardly walk.

Kaori said she is never very worked up before her matches and does not study her competitors carefully. In her matches it seems she doesn’t move much. She has a talent for unbalancing her opponents and seizing opportunities.

Chiharu Icho won a silver medal in the 48 -kilogram division at the Olympics in Beijing in 2008. She lost convincingly on the final to Canadian Carol Huynh, who Chiharu had beaten in their previous two encounters. A high point for Chiharu in Beijing was pinning Ukraine’s Irini Merleni in the quarterfinals, Merleni beta her in Athens in 204 to take the gold.

After Beijing the sisters hinted that they would retire and then said they won’t retire and will aim for the Olympics in London in 2012.

In February 2009, Kaori Ichi announced her engagement to her 32-year-old South Korean coach.

Kaori Icho Wins Historic Third Wrestling Gold at the London Olympics in 2012

Kaori Icho became the first Japanese woman to win a gold medal at three consecutive Olympic Games, beating China's Jing Ruixue in the final of the 63-kilogram freestyle wrestling division. Icho's first match was against Canada's Martine Dugrenier, who took a period from her in the semifinals of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Icho, 28, seemed to gain momentum by beating Dugrenier and then easily cruised into the final, where she dominated Jing 2-0 (3-0, 2-0). Jing took third at the 2011 World Wrestling Championships. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The victory in the final extended Icho's winning streak to 72. Her last loss was a default in May 2007, in which she had to withdraw from a match against a Taiwan wrestler in the Asian wrestling championships due to a thigh injury. Before the incident, Icho had won 81 matches in a row. Despite her historic achievement, Icho seemed dissatisfied with her performance. "I think I could've done a bit better in the matches. However, I scored points with tackles, which was good," she said. She also said winning three consecutive gold medals was never her goal, but added that, "after finishing the competition, I'm pleased with what I've achieved."

After winning the gold, Icho revealed she had competed with torn ligaments. According to Icho, she tore ligaments in her left ankle during a practice session held Saturday. "Out of three ligaments [of the ankle], one was completely torn and another was partially torn," Icho said, adding she had a painkiller injection before the final. Despite the injury, Icho was dominant throughout her matches--she allowed only one point in all four.

Describing wrote in the competition and the reaction in the Japanese rooting section, Nobuaki Ono wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, The atmosphere kicked into high gear when Icho scored her brilliant tackle. The people in the stands rose from their seats and started a countdown to her victory. When she clinched the victory, Icho clapped her hands and shouted with joy. When the referee raised her right hand to indicate her win, she raised her left fist, and finally broke into a smile. "You did it, Kaori!" Chiharu, 30, said through tears, waving at her sister. "Just great! To keep winning is hard to do. Kaori is really great," Chiharu said. [Source: Nobuaki Ono, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

"I don't want to boast, but I'm really proud of my daughter," said Toshi, Icho's 63-year-old mother, wearing a hachimaki headband with "hissho" (certain victory) written on it. "We'll support her if she wants to go," her mother said about the next Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. Before the match Icho said: "I wasn't aiming for a third consecutive Olympic medal. Rather, I wanted to focus on competing with my own style." However, after scoring the victory, she beamed with joy in contrast to her usual cool attitude. "I'm overjoyed to make history," Icho said.

Kaori Icho’s Wrestling

Nobuaki Ono wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “As a wrestler in the 63-kilogram division, Icho is relatively light. After weighing themselves and eating, her opponents often weigh five kilograms to six kilograms more than her on match days, she said. Kazuoki Sawauchi, president of the Hachinohe Wrestling Association of Aomori Prefecture said: "Athletes have to compete in four matches during the Games [through the final]. I told her to fight defensively and protect a single-point lead, while not becoming tired." Sawauchi trained her during primary and middle school and still advises her.. [Source: Nobuaki Ono, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

Icho, however, aimed to compete differently at the London Games than she did at her previous two Olympics "I used to tire my opponents out and then score a point in the last 30 seconds. But this time I wanted to score a point in the first 30 seconds and gain additional points in the remaining time," Icho said. She stuck to her plan in London from her first match. Chikara Tanabe, winner of the bronze medal in the men's freestyle 55-kilogram division at the 2004 Athens Olympics, coached Icho when she participated in the national men's team camp. "Maybe [Icho] thought she couldn't keep on winning at the world level after the Beijing Games," Tanabe said.

Icho had considered retiring from wrestling after the Beijing Olympics. Her elder sister Chiharu, who won the silver there, her second following the 2004 Athens Olympics, retired after Beijing and became a high school teacher in their hometown of Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture. The siblings' goal was to win gold medals together at the Olympic Games, so Icho felt her passion for wrestling fade after her sister's retirement. After the Beijing Olympics, Icho began living by herself in Tokyo.

Kaori Icho Wrestles Men

Nobuaki Ono wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Icho “reignited her passion for the sport by practicing with male wrestlers. She visited universities and Self-Defense Force camps to practice with strong male competitors, even joining the training sessions of wrestlers who participated in international tournaments. There she realized her wrestling skills were far inferior to those of male competitors. "I think I would have enjoyed wrestling more if I were born a man. I regretted being a woman," Icho said. [Source: Nobuaki Ono, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

She also said she learned reaching the top in women's wrestling does not equate to full mastery of the sport. The three-time Olympic champion believes she will become even stronger by learning from men. "These three Olympic Games have passed by in a flash. I feel like the Rio de Janeiro Games are just around the corner," she said.

Hitomi Obara Wins Wrestling Gold at the London Olympics in 2012

Hitomi Obara added another gold to Japan's medal tally the same day by defeating Azerbaijan's Mariya Stadnyk in the final of the 48-kg division. Obara, 31, won the gold in her first Olympic appearance. Obara advanced to the 48-kg final after defeating defending Olympic champion Carol Huynh of Canada in the semifinals. The scenario in the final mirrored that of the 2011 World Wrestling Championships, in which Obara also beat Stadnyk in the final. Stadnyk again took the first period, by an even greater margin than last time with 4-0. But Obara rebounded to win the following two 1-0, 2-0. It was the first time Japan has won the 48-kg division in the Olympics.[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

Obara was overjoyed. "I really can't believe it. I couldn't have won the gold medal by myself," she said. "I wasn't alone when I stood on the mat--I felt the power of the people who supported me. That's why I didn't give up [in the final]. The happiest moment for me was showing my smiling face to everyone who supported me," Obara said.

Nobuaki Ono and Keiichi Kojima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Wrestler Hitomi Obara hit bottom along the way in her quest for Olympic glory, but she climbed back up to reach the very top of her sport Wednesday, winning her first Olympic gold medal in the women's 48-kilogram freestyle. After losing the first period of the final to Mariya Stadnyk of Azerbaijan, Obara went on the offensive as calls of "Obara" grew louder at the ExCel Arena. As the buzzer sounded to end the match and seal Obara's come-from-behind win, she raised her arms high in triumph but soon collapsed on the mat. She then cried for joy, covering her face with her hands.It was a grand finale for the 31-year-old who had decided to retire after the London Olympics. [Source: Nobuaki Ono and Keiichi Kojima,Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

Obara has won six world titles at 51 kilograms, a class not featured in the Olympics. She sought a ticket to the 2004 Athens and 2008 Beijing Games in the 55-kilogram class, but was unable to defeat rival Saori Yoshida, 29. Obara's repeated failure to secure an Olympic berth soured her on wrestling and at one point her weight grew to more than 70 kilograms. She also suffered from depression after she failed to get a ticket to the Athens Olympics. However, Obara decided to stage her last challenge after her younger sister Makiko, who retired in 2010 as a 48-kilogram-class wrestler, urged her to strive for the London Olympics. In the end, Obara was able to return to the mat in the 48-kilogram class thanks to strict weight control and training.

After Obara won the coveted gold medal, her husband Koji, 30, rushed to the front row of the stands and called out her name. After yelling, "Good for you!" he dabbed his eyes for a while. Having recovered, he started proudly repeating in English, "She is my wife," to those around him, which brought strong applause from the spectators. When she noticed Koji trying to squeeze his way along to her, Obara jumped and waved her hands.

Her father, Kiyomi Sakamoto, who always encouraged her, praised her for coming all the way back from the bottom. "It's like a dream," he said, wiping away tears. Sakamoto said he named his daughter Hitomi in the hope she would always rise again if she failed. Her name is made of three Chinese characters that mean sun, rising and beauty. Hitomi's mother, Mariko, supported her daughter by cooking dishes suitable for her strict weight control as she lowered her class from 51 kilograms to 48 kilograms. "It was great because she was able to complete her life as a wrestler with such glory. I never thought we'd see the day," Mariko said in tears.

Japanese Men’s Olympic Wrestling

Japan has won medals in men’s wrestling in every Olympics since 1952 with exception of the boycotted 1980s Moscow Games. Japanese men took two wrestling bronze medals at Athens: in the 55 kilogram and 60 kilogram divisions. They won a silver and a bronze medal at the Beijing Olympics. They won gold medals in London in 2012, , marking the 15th consecutive Olympics since the Helsinki Olympics for Japanese wrestlers to take home a medal.

In women’s wrestling, which has been an official event since the Athens Games, the female wrestlers Yoshida Saori and Icho Kaori won consecutive gold medals at the Athens and Beijing Games in their respective 55-kg and 63-kg divisions. Japanese female wrestlers have won medals in every weight division. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

In September 2007, Makoto Sasamoto became the first Japanese wrestler to win a medal in Greco-Roman wrestling, taking a silver in the 60-kilogram division in the world championships at Baku in Azerbaijan

Tomohiro Matsunaga won a silver medal in the men’s 55-kilogram division at the Olympics in Beijing in 2008. He was defeated by Henry Cejudo, the son of illegal Mexican workers, in the gold medal match. To make to they finals Matsunaga beat the reigning world champion from Russia in the his semifinal bout with a pin. Kenich Yoto won a bronze in the 60-kilogram division.

Yonemitsu Ends 24-Year Wait for Olympics Wrestling Gold

Yomiuri Shimbun Tatsuhiro Yonemitsu won the gold medal in the men's 66-kilogram freestyle wrestling at the London Olympics, becoming the first Japanese gold medalist in men's wrestling since the 1988 Seoul Olympics. "I feel like I'm dreaming. I didn't think I could win the gold medal. I had always wanted to surpass myself in the past," said an emotional Yonemitsu, who became Japan's 20th male Olympic wrestling champion. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 14, 2012]

Keiichi Kojima wrote Yomiuri Shimbun, “Yonemitsu approached his final bout with a determined look and shouted, "Let's do it!" to his coach, who had walked him to the stairs leading to the mat. The highlight of the final was the second period, when Yonemitsu tackled his Indian opponent and lifted him on his shoulder. The next moment, Yonemitsu slammed him back-first onto the mat to wild applause. When Yonemitsu was declared the winner, he jumped for joy and did a crude pirouette in the air before doing a victory lap around the mat holding a Japanese flag on his back. The audience applauded again when he was hoisted onto the shoulders of two cornermen.

Yonemitsu, 26, polished his tackling skills, using cats' jumping techniques as a source of inspiration. When tackling an opponent, he hunches his back and jumps forward without a runup, using his entire body as a springboard, he said. His one-of-a-kind tackling style helped to confuse his opponents. Eleven years after taking up wrestling, Yonemitsu now stands on top of the world with techniques no one else could imitate.

Yonemitsu read books on the art of war as part of his training. As part of his regimen, he read books on the art of war such as "Go Rin no Sho" (The Book of Five Rings) written by Miyamato Musashi, a noted swordsman in the early Edo period (1603-1867), and "The Art of War," written by Sun Tsu in ancient China. As a child, he adored fighters and martial artists, especially Bruce Lee. He imitated Lee's movements and collected figures of Lee.

He joined a judo club in middle school and also tried sumo. When he participated in a sumo meet held in his hometown of Fuji-Yoshida, Yamanashi Prefecture, he was approached by Toshiro Fumita, the manager of a wrestling club in Nirasaki Technical High School in the same prefecture. Fumita told Yonemitsu, "You're a talented wrestler and could go to the Olympics." Yonemitsu entered the high school and started practicing wrestling under Fumita's guidance.

Besides using excellent technique, Yonemitsu is physically blessed as a wrestler. He has long limbs--his arm span exceeds his height by 15 centimeters--and a flexible body. When he was a child, he was able to jump through his arms when he linked his hands together. Fumita said: "If he can reach an opponent's leg, he can tackle him."

Yonemitsu won the second prize at an interschool wrestling championship when he was a third-year high school student. He was often told he could win an Olympic gold medal. Encouraged by the comments, Yonemitsu aimed for the London Olympics. He won a ticket to the Games by winning the all-Japan wrestling championships in December 2011. After the final at the Olympics, Yonemitsu said: "It was an exciting match. If I hadn't won, I wouldn't be a real champion. I'm satisfied with my performance in the final. I'm glad that my wrestling has progressed a step further."

Shinichi Yumoto Win a Bronze Medal in Wresting as His Twin Did Before

Kyodo Japan's Shinichi Yumoto emulated his twin brother Kenichi by winning an Olympic bronze medal in men's 55-kilogram freestyle wrestling on Friday at the London Olympics. Shinichi fell in his semifinal to Georgia's Vladimer Khinchegashvili but won his bronze medal match over Beijing bronze medalist and 2006 world champion Radoslav Marinov Velikov 2-0 to match his brother's feat in the 60-kg class in Beijing. Yumoto won the close contest on the final technical point in the second period that was scored 1-1. [Source: Kyodo, August 11, 2012]

"I wanted to fight in the final," said Yumoto, who could only manage eighth place at the world championships last year. "Kenichi took the bronze four years ago and it was a great encouragement for me to get this far and win this medal." The Olympic debut of Japan's entrant in the 74-kg class, Sosuke Takatani, lasted just four minutes as he lost his qualification match against Azerbaijan's Ashraf Aliyev in two periods without scoring a point. "I wanted to enjoy this more," said the 23-year-old. "To be finished in one match is pretty lame."

Ryutaro Matsumoto wins bronze for Japan in Greco-Roman Wrestling

Adam Westlake wrote in the Japan Daily Press, “After almost being eliminated entirely without an Olympic medal to his name, Japan’s Ryutaro Matsumoto turned things around to defeat Kazakhstan’s Almat Kebispayev on Monday and win the bronze medal in men’s Greco-Roman wrestling 60 kilogram (132 pounds) division. Matsumoto, a 2010 world silver medalist, was down 2-1 before he could come back and score a point from a back hold on Kebispayev. After that, there was no stopping him. The Japanese wrestler got his opponent on the mat and turned him for another three points. [Source: Adam Westlake, Japan Daily Press, August 7, 2012]

By the third period, Kebispayev was running on fumes, and the 2011 world silver medalist couldn’t prevent his fall to the mat at the hands of Matsumoto. At 26 years old, the Japanese Olympian has secured the 15th consecutive Olympic medal in the men’s Greco-Roman wrestling for his country. When asked about his achievement, he commented that at home most of the media was focused on the women’s wrestling. While well deserved, he says it was nice to bring some attention to the men’s, and it felt really great to continue Japan’s ongoing streak of wrestling medals.

Matsumoto started off strong in the tournament, earning victories against Turkey’s Rahman Bilici, and Tarik Belmadani of France. But unfortunately he lost a close match against the eventual gold medal winner Omid Haji Noroozi of Iran. He was hopping to make it as far as the final round, which hasn’t been done by Japan since the 2000 Games in Sydney, when Katsuhiko Nagata won silver.

Ryota Murata Wins Japan's First Boxing Gold since 1964

Ryota Murata beats Brazil's Esquiva Falcao to win Japan's first Olympic boxing gold medal since Tokyo 1964. A two-point penalty in the final round for the Brazilian helped Murata secure Japan's second boxing gold of the games . Falcao and his brother, Yamaguchi, who won the bronze medal as a light heavyweight, both fell short of winning Brazil's first Olympic boxing gold medals. In December 2012, Murata was given a special award at the Japan Grand Prix at the 62nd Japan Sports Awards. Established by The Yomiuri Shimbun, the awards are given every year to the most prominent athletes and teams in the world of sports. [Source: BBC, August 11, 2012; Yomiuri Shimbun, December 15, 2012]

Jiji Press reported: “Middleweight Ryota Murata won Japan's first Olympic boxing gold in nearly half a century, narrowly defeating Brazil's Esquiva Falcao Florentino in a hard-fought contest. The victory capped a fairy-tale return to the ring for Murata, who briefly retired after failing to qualify for the 2008 Beijing Olympics but later changed his mind. Murata's boxing life has had its ups and downs, but his hard work since coming out of retirement has paid off with a gold medal. However, Murata feels this is just another step on his life journey. "My worth won't be decided by this medal. How I live after the Olympics will decide that. I'll live my life so it befits the medal," Murata said.[Source: Jiji-Daily Yomiuri, August 13, 2012]

Although history had been against him, Murata felt his 14-13 win had always been a genuine aspiration. "Winning a gold medal wasn't just a dream. It was a realistic target," Murata said after the bout. Using his trademark body blows, Murata was effective in close in the first round and built up a 5-3 lead against Florentino, whom he also defeated in the semifinals of last year's World Championships.

The Brazilian southpaw changed tactics in the second round, and used his footwork to keep Murata out of range, where his body shots were less potent. The strategy worked, and Murata's lead was cut in half after this round. Florentino come out swinging in the final round, unleashing several heavy left hooks that forced Murata to the ropes. Murata countered with some more body blows, and a tiring Florentino began resorting to clinching to stop the flurry of punches. The referee warned Florentino for holding, which gave Murata two vital points. Murata squeaked into the final by beating Uzbekistan's Abbos Atoev in the semifinal the previous day. The Japanese boxer had been behind after two rounds, but dominated the third to advance.

Murata's gold was Japan's second boxing medal in London, following Satoshi Shimizu's bronze in the bantamweight division Friday. This was the first time Japan has won multiple boxing medals at an Olympic Games. The nation's last boxing gold was won by bantamweight Takao Sakurai at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Murata Fought with Late Mentor in Mind

Keiichi Kojima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, "Believe in yourself!" middleweight boxer Ryota Murata repeatedly thought as he fought his way to Japan's first Olympic boxing gold medal in 48 years. In repeating the mantra to himself, Murata was honoring the memory of his late mentor, who constantly told him he had to believe in himself. Murata met teacher Maekawa Takemoto — whom he still looks up to as a lifelong mentor — at a boxing club of Minami-Kyoto High School in Kyoto. The enthusiastic teacher often told him: "Believe in your possibilities. Strive to realize your dream." [Source: Keiichi Kojima, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 13, 2012]

Before Murata met Takemoto, he was unable to wholly devote himself to anything. When he was a first-year student of Fushimi Middle School in Nara, he dyed his hair brown and was often scolded by his homeroom teacher. When the teacher asked Murata whether there was anything he wanted to do, Murata immediately said "boxing" because he wanted to be stronger when he fought with other boys.

The teacher introduced him to a boxing club at a local high school, but he quit the club in two weeks as he found the training too hard. Murata later recovered his desire to learn how to box, and when he had to decide which high school to go to, he chose Minami Kyoto High School, which is famous for its boxing club. At the high school, Takemoto sharply rebuked Murata when he had fights with other boys outside the ring or skipped training. However, he took Murata's concerns seriously.

At a training camp, it became a custom for the club's members to express their worries to Takemoto before they went to bed. "Even if you win a boxing match, it doesn't mean you can win in society," Takemoto repeatedly told the club members, "Be a person who others can trust." Murata was attracted by Takemoto, who was always up-front with his students, and he gradually became enthusiastic about training. After entering Toyo University, Murata quickly gained a reputation for the heavy punches he delivered from his 182-centimeter, 77-kilogram body. He soon decided he wanted to go to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. However, in those those days it was said that Japanese middleweights could not compete at a world-class level because there were many middleweights with overwhelming power.

After Murata was badly defeated as a member of a Japanese delegation competing in the preliminaries for the Beijing Olympics in March 2008, he gave up boxing and went to work for Toyo University. Murata later learned that Takemoto had gone to cheer for him at the preliminary match but cried in a dressing room after Murata was defeated. Takemoto dreamed of watching his student box in the Olympics. Murata later said that deep inside he may have given up on winning the match almost from the beginning.

Murata returned to the boxing ring in autumn of 2009, a move that made Takemoto ecstatic. But in February the next year, Murata was shocked to hear that Takemoto had committed suicide. He was 50. "I couldn't believe why a person who constantly told me to believe in myself would do that," he said Murata heard Takemoto had relationship problems. The venue of Takemoto's memorial service had an overcapacity crowd of mourners, including Takemoto's former students.

Murata swore to himself to make Takemoto's dream come true. He won a silver medal in the World Championships last year, winning a ticket to the London Olympics. Before the semifinals, Murata saw a dark blue T-shirt printed with white letters saying, "Takemoto Gundan" (Takemoto Corps). Hajime Nishii, 45, a teacher who used to train members of the boxing club with Takemoto at Minami-Kyoto High School, made the shirts to keep Takemoto's teaching in mind. Murata said seeing the T-shirt motivated him to do his best and he felt as if Takemoto was watching in London.

Shimizu Wins Olympics Boxing Bronze Medal After Referee Sent Home

Satoshi Shimizu lost his semifinal in the men's bantamweight boxing but left the Olympics with a bronze medals. Shimizu succumbed to Britain's Luke Campbell, a 2011 world silver medalist who dominated from the start for a resounding 20-11 victory. According to RIA Novosti: “The British southpaw came out strong, mixing up his combinations well and registering several stinging lefts to go 5-2 up round one. Shimizu belied his crude style to fare better in the second round but was still overpowered by Campbell and went 11-6 down. [Source: RIA Novosti, August 10, 2012]

Earlier Shimizu had a loss turned into a win after an appeal against his defeat by Azerbaijan’s Magomed Abdulhamidov was decided in his favor. The boxing referee from Turkmenistan who made the initial call was expelled from the London Olympics for his handling of the bout. Boxing's governing body, AIBA, released a statement saying the referee Ishanguly Meretnyyazov "is on his way back home". [Source: Ian McCourt, The Guardian, August 2, 2012]

Ian McCourt wrote in The Guardian: In the bantamweight bout “Magomed Abdulhamidov of Azerbaijan fell to the canvas six times in the third round against Satoshi Shimizu of Japan, yet still won a 22-17 decision. Meretnyyazov allowed the fight to continue after each tumble and he enraged the Japanese team by fixing the headgear worn by Abdulhamidov, who had to be helped from the ring after winning. AIBA overturned the result, saying Meretnyyazov should have counted at least three knockdowns and stopped the bout.

Hirome Miyake Makes History with Weightlifting Silver

Hiromi Miyake daughter of Mexico Olympic weightlifting bronze medalist Yoshiyuki Miyake, became the first Japanese woman ever to win a medal in Olympic weightlifting, taking the silver medal in the women's 48-kilogram division at the London Games. Miyake, 26, made a good start by lifting 83 kilograms on her first snatch attempt, tying the national record. She easily set a national record by lifting 85 kilograms on the second attempt and 87 kilograms on the last try. Miyake continued to advance by lifting 108 kilograms in the first attempt for clean and jerk and 110 kilograms in the second attempt. Miyake, lifted a combined total of 197 kilograms, breaking the national record. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, July 29, 2012]

Nobuaki Ono wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Hiromi Miyake achieved her long-cherished dream of winning an Olympic medal on her third try. Her first appearance in the Games was in the 2004 Athens Olympics. However, Miyake suffered acute lower-back pain just before the event and finished ninth, just missing an Olympic diploma, which is given to each of the top eight competitors in all Olympic events. In 2005, Miyake injured a hip joint at the world championship, and the injury lasted until the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Due to the injury and stress, her weight dropped to 47.35 kilograms; her division has a 48-kilogram maximum weight limit. She finished sixth. At that time, various parts of Miyake's body began aching. Her father, who is also her coach, said the pain was caused by trying too hard to lose weight while she was still growing, as well as strenuous training.

Miyake participated in the Athens Olympics when she was a first-year student at Hosei University. Her weight was 53 kilograms at that time, so she had to lose five kilograms in three months to take part in the 48-kilogram division, in which she had a better chance to win a medal. Even though she began experiencing aches and pains in various parts of her body after the Beijing Olympics, Miyake could not give up her dream of winning an Olympic medal. To reduce the burden on her body, she began varying the intensity and amount of her practice. For example, she did not use barbells during practice sessions on certain days. The efforts bore fruit last year. In June 2011, Miyake won the 53-kilogram division title of the All-Japan championships by lifting a national record of 207 kilograms for the division. The win and the record boosted her confidence for the London Olympics.

Keijisuke Kojima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Miyake's weightlifting career began when she was a third-year middle school student and asked her father, Yoshiyuki, to teach her the sport. However, Yoshiyuki, now 66, initially opposed the idea. He still suffered pains in his right wrist, knees and other joints, the cost of heaving heavy weights for many years. Her mother, Ikuyo, now 62, graduated from music college and had taught Hiromi to play piano since she was 4. She wanted her daughter to become a piano teacher. But Hiromi persisted and Yoshiyuki eventually let her try to lift weights, finding her form was good. [Source: Keijisuke Kojima, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 30, 2012]

Only a few months later, Hiromi could lift 42.5 kilograms, almost the same amount Yoshiyuki could during his high school days. Yoshiyuki finally made up his mind when he asked his daughter, "Do you want to win a medal at the Olympics?" and she nodded. During training sessions, Hiromi often lifted a total of more than 20 tons a day. Thanks to the one-on-one coaching, she made her Olympic debut in Athens in 2004, finishing ninth. She sought to make up for this disappointing result during the 2008 Beijing Games, but finished just sixth due to pain in her hip joints.

She was particularly upset when her father was blamed for her bad performances. In March 2009, Hiromi left her home in Saitama Prefecture and traveled to Okinawa Prefecture without telling her father, as if she was running away from him. Yoshiyuki had just begun to form a training plan for the London Olympics. In Okinawa, Hiromi visited close family friend Mari Taira, a 36-year-old high school teacher who competed as a weightlifter in the 2000 Sydney Games."I can't have confidence in myself," a tearful Hiromi said, wondering if she should retire. Taira, however, realized Hiromi's real feelings when Taira found Hiromi had brought her practice shoes and belt with her. "I'm sure your father has the same feelings," she said.

Hiromi trained at Taira's school, growing more relaxed during her weeklong stay in Okinawa Prefecture. When Hiromi returned home, Yoshiyuki did not say anything. He soon learned there was nothing to worry about when his wife told him where Hiromi had gone. Father and daughter then started their efforts for the 2012 Games. "I want to prove I can [win a medal] as we've worked hard as father and daughter," Hiromi had said, and she fulfilled that goal.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013