MANGA INDUSTRY IN JAPAN

Used manga store Manga has traditionally been a very lucrative commercial industry with a devoted following. Manga sales now account for a third of the book and magazine market in Japan — which translates to about $10 billion in annual sales. The industry employs about 40,000 artists, editors, writers, and publishing and marketing people. Tens of thousands are involved in printing and selling them. Major manga publishers include Kodansha Ltd, Shueisha Inc and Kadokawa Group Publishing Co,

About 2 billion manga are sold ever year (40 percent of all books and magazines in Japan). Successful manga are usually made into animated television shows films, which are very popular in Japan and have a growing cult audience in the United States and Europe. They also generates video games, games, collection cards, and characters goods. The character goods market alone is worth $3.5 billion.

In 2007, the sale of manga books and magazines stood at around ¥470 billion.Most years about 20 to 30 percent of television dramas are derived from manga. Some attribute the success of the manga formula in Japan to the long commutes of Japanese workers and their need to do something on the long train rides.

Manga Magazines and Books in Japan

Shohen Jump Much of the manga that people read is sold in thick magazines printed in black and white on thin, easy-to-thumb paper stock similar to that used to make phonebooks. Popular weekly manga like Shonen Jump, published since 1983, and Shonen Magazine sold up to six million copies per issue in its heyday. Other manga magazines include Melody and Morning. Shogakukan’s CoroCoro Comics features “Pokeman”and “Doramon”. Shonen Jump’s target audience is teenage boys.

One of the main difference between Japanese manga magazines and American comic books is that the magazine give artists more freedom and pages to work with. Manga expert Frederick Schodt said, “Most American artist were limited to an allotment of say 30 pages a month which made it difficult to create long-arc stories which complex character development.”

The weekly manga magazine Shukan Shonen Jump is the best selling manga magazine and the best selling magazine in Japan but has seen its weekly circulation shrink from , 3.8 million in 1998 to 1.9 million in 2007.

Manga magazine sales have declined for 13 years. The monthly Gekkan Shonen Jump sold 1.5 million copies a month at its peak. Sales deceased to 350,000 in 2007. Publication was suspended in July, 2007. Some publishers are beginning look at them primarily as vehicles to sell books .

The sale of manga books is relatively healthy Manga stories that are compiled and sold as books sell well. In 2005, sales of manga books reached ¥260 billion in sales a year, outselling manga magazines for the first time. The book forms of “One Piece” and of “Naruto” — both popular in manga magazines — had initial printings of 2.4 million copies.

Manga Artists

first Shonen issue Manga artists are call “mangaka”. Currently there are about 4,000 mangaka working full time, plus thousands of part timers and wannabes. Being a manga artist is something that many Japanese say would be their dream job. Many of those who do make their living at it, work all night, sleep all day and get most of the meals from convenience stores.

The pay is generally is very low. Starting salaries can be less than $500 a month. A background artist may make around $1,000 a month. Up and coming or even established artists are paid about $175 a page and can make about $2,500 a month producing four pages of manga for a weekly magazine. Even this is not much when you live in the world’s most expensive cities. Company workers often make twice or three times as much and get good benefits. One publisher told the Daily Yomiuri that ratio of professional mangaka that can make ends meat from their work is about 1 in 100,000. Many manga artists have to quit because they can not live on what they make.

Manga artists have traditionally had volatile relationships with the editors, often complaining or being poorly paid, treated as fools and verbally abused. Sharon Kinsella wrote in “Adult Manga”, "The manga world vibrated with secrets and rumors about artists abducted by their editors, artists who escaped through toilet window, artist who fled their studios overnight, artists who beat up their editors. leaving them with facial scars and artist who committed suicide."

Star mangaka can make a lot more. Famous artists earn income from their magazine jobs, books sales — that can sometimes be in the millions — and form works made into television series and films. Rumiko Takahashi was the top earner among manga artists in 2002. Her 15 manga books have sold more than 30 million copies.

Some mangaka take themselves and their work quite seriously, regarding themselves as artist and there work as art. One manga publisher, Shogakukan, lost five panels of art by the mangaka Maloto Raiku from the manga series “Konjiki no Gash!”, which ran in a manga magazine from 2001 to 2007 and was made into a television series. The publishers offered ¥500,000. Raiku demanded ¥3.3 million and sued when the publisher refused to pay it. Raiku based his demand in the price his works fetch on Internet auction sites. As a rule mangaka are very reluctant to give up their works or give permission to use copyrights.

Making Manga

Mangaka have traditionally used dip pens and high-quality paper. Many professional mangaka insist it is best to work out the dialogue first and then left the story pump life into the images. Some manga readers insist that the text and story are more important than the drawings. As is true with film, they say there are plenty of examples of manga with great drawings left hollow by weak stories and characters as well as roughly-made manga that are a joy to read because the story and characters are good.

Comic Studio is software that enables users to draw manga on a personal computer. Some use it to draw and make images from scratch on their computers. Others use it to add finishing touches to works drawn by hand.

Digital Manga Opens Global Doors for Aspiring Artists

Makoto Fukuda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Many how-to books for drawing manga published in my childhood often said, "Manga should be drawn with a pen on paper." Large sections of these books were dedicated to introducing different types of pens and how to draw lines. However, nowadays it has become more common to draw manga on a computer--a method known as digital manga. Useful software can be used to create special effects, such as "speed lines," that are very difficult to draw freehand without a lot of practice. Software can also be used to save and reuse backgrounds and compositions. [Source: Makoto Fukuda, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 1, 2012]

The traditional methods of drawing on a piece of paper, tearing it up if it's not good, and then drawing on another piece of paper is now a bygone practice. Drawing manga has become much easier. The strength of digital manga is that unlike its pen-and-paper counterpart, it can be read all over the world through the Internet.

Sad State of the Manga Industry

Shuho Sato, author Black Jack ni Yoroshiku (Say Hello to Black Jack), a popular manga about a conflicted doctor-in-training working at a university hospital, ended a royalty contract with his publisher Kodansha and "completely liberalized" the secondary use of the manga. Kanta Ishida wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Any data regarding Black Jack ni Yoroshiku distributed through Sato's website "Manga on Web" (http://mangaonweb.com/welcome.do) can be copied, adapted, parodied or animated without his permission--regardless of whether it's for commercial or private use. Anyone can publish the series without having to pay Sato any royalties. It's probably unprecedented to make such a popular manga "copyright free." [Source: Kanta Ishida, Daily Yomiuri, November 2, 2012]

The reason Sato decided to do this sprang from a tough situation involving the publishing circle and fans of the manga. In an essay titled Manga Binbo (Manga poverty) released in May by PHP Inc., Sato reveals the naked truth that the paper- or magazine-based manga industry has already reached its limit.

Popular mangaka usually hire several assistants. Taking into account production costs, including labor, mangaka are usually left in the red. Even if mangaka expect income from royalties, they may still struggle to make a living unless the comics sell well. Also, when a manga becomes a hit, publishers sell the right of secondary use without asking authors.

Sato despaired that he wasn't treated appropriately as an "author," and decided to circumvent publishers and directly distribute his work to readers on a trial basis. Hence "Manga on Web"--a system to release his manga on the Internet. In so doing, Sato seems to have decided to shun paper and introduce people to his work on the Internet.

Studying Manga Art in Japan

Moe Manga eyes The number of universities that offer courses in manga has been increasing. Kyoto Seika University offers classes in manga and anime drawing. “I like it here because you get totally immersed in the skill training” of manga and animation, a Stanford graduate student who studied there told the New York Times. “It has turned out to be a lot of fun.” More and more foreign students coming to Japan to study modern Japanese arts, feeling they may help them advance their careers in animation, design, computer graphics and the business of promoting them. And Japanese universities are glad to have them as they face declining enrollments as a result of Japan’s declining birth rates. [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, December 26, 2010

Li Lin Lin, 28, a student from northeastern China who attends Digital Hollywood University, a school in Tokyo that specializes in animation and video games, told the New York Times that upon finishing her degree, it would probably be “easy” to find a job in the animation field in China. The real trophy, she said, would be getting job experience in the country of manga. Ms. Li is especially interested in working for a Japanese animation studio. “I think you can do almost anything back home once you get a degree and animation working experiences in Japan,” said Ms. Li, emerging from her class on digital animation coloring one Saturday afternoon.

Hidenori Ohyama, senior director of corporate strategy at Toei Animation, tod the New York Times it was possible that international students could end up at Japanese companies like his. “If they apply, take our tests and pass, they will become employees just like anyone else,” he said. His company, a leading animation company that has produced “Dragonball” and “Slam Dunk” films, has Romanian and Korean producers, among other foreign citizens, Mr. Ohyama said.

None of the animation-themed Japanese university programs seem to be on the international radar yet, Kison Chang, a training manager at Imagi Studios, an international animation production studio based in Hong Kong, told the New York Times. But he said students studying in Japan who ended up with solid work experiences at Japanese studios could be prime candidates for international recruitment.

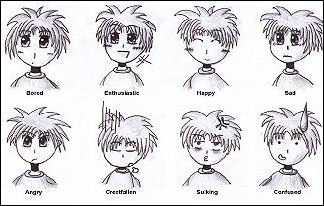

Manga emotions Another possible reason that the programs have not received international attention is that the language of instruction is Japanese.Tomoyuki Sugiyama, president of Digital Hollywood University, conceded that language might be a serious barrier, especially for Western students. “If we had an English-based program at the graduate level, for example, we would be inundated with Western students almost instantly,” he said.

Nevertheless, at Kyoto Seika University, which established the country’s first manga program, the number of foreign students in it has risen to 57 currently out of a total of 800 students in the program from just 19 in 2000. Since it was founded in 2005, Digital Hollywood University has seen its international students grow to 84 this year, roughly 20 percent of its student body, from just one when the school began.”I want to see it grow to 50 percent of the entire students in the very near future,” Mr. Sugiyama said.

In the past 10 years, more than a dozen university departments and programs have been created to offer a degree or a cluster of courses meant as a concentration in manga, animation and video games, and a similar number of vocational schools offer training in the art. At Digital Hollywood, with campus buildings spread across the Akihabara area in Tokyo, the nation’s capital for otaku, or nerds, students from Korea, China, Malaysia, Taiwan and other Asian countries, who constitute the bulk of the international student body, mingle with Japanese students.

Manga School Curriculum

Large manga eyes

said to be inspired

By Betty Boop The curriculum at the schools usually includes courses on drawing, coloring, and motion picture production, as well as film directing, writing plays and the study of copyright laws. [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, December 26, 2010]

In recent years, universities in China and Korea have also begun offering manga and animation programs, drawing many students locally. But Keiko Takemiya, dean of the manga program at Kyoto Seika University and a famed manga artist, said there were differences. “What they teach in Korea is mostly cartoons like you see in the U.S.,” she said. “They don’t quite teach the “story manga.”

Story manga is known for its feature lengths and distinct story lines, as compared with the one-liner cartoons with gags and jokes. Ms. Takemiya said that manga’s secret was in its limitless boundaries in form and content, and that the sheer number and the kind of manga available in Japan far exceed those in other countries.

And that includes adult-themed manga/animation that may or may not include sexually explicit content that many other countries are staying away from. “What they teach in China is animation meant for children,” said Mr. Sugiyama of Digital Hollywood. “But what we teach is geared towards both children and adults.”

A professor at Kyoto Seika University, Jacqueline Berndt, one of the few non-Japanese faculty members in the field, said language and culture were an obstacle to wider acceptance of the programs.In addition, she said, the manga and animation programs might not have yet been fully organized into a coherent body of knowledge and theories that scholars from other countries can understand and appreciate.

One reason the art has never been compiled into a structured body of knowledge: In a country where public education has been strictly administered, manga and animation have thrived in a creative way precisely because they operated outside the purview of the system, free from any supervision from the authorities. “Manga flourished as a counterculture to the establishment academia,” Ms. Takemiya said. “There was actually a resistance to the idea of organizing the art into an academic program” in the industry.

Most Japanese scholars and teachers acknowledge that the body of knowledge they teach is still in the process of being organized into a system. “We put together and offer classes that we believe will be of use to people who are going into the trade, but if we wait till manga and animation studies are fully structured and organized academically, that’s too late,” Mr. Sugiyama said. “In a world where creative content is digitalizing and globalizing, we need to train young people in these arts now.”

Amateur Manga in Japan

There is also a large underground, amateur manga scene. Thousands of artists, known as “dojinshi”, are active and sometimes they attract large cult followings. Reaching their audience through the Internet and manga events like the Comic Market, they produce a staggering variety of work. It is often very sexual and feature images of current pop idols and political figures. Sometimes the quality is quite good. Sometimes it looks rough and amateurish.

Only eight percent of dojinshi make any money. A small number are able to sell 20,000 or 30,000 copies of their manga for around ¥500 a piece a make a meager living. For the rest manga making is a hobby, and being able to cover printing costs is an accomplishment. The dream of many of the artist is to be discovered and land a good-paying job with an established manga weekly. The whole scene is bit like garage bands and indie record labels, only more diverse and fragmented.

See Comic Mart Below

Manga Studies Gain Momentum

Asako Kisui wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “With many young people aspiring to careers in the manga and anime fields, universities are offering courses to nurture the next generation of pop culture creators. The relevant curriculums are segmented or specialized, and include graphics and animation, Internet anime and manga, and character formation. From the next academic year, new courses on "gag manga" and character figures will start at some universities. [Source: Asako Kisui, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 14, 2012]

"The manga market generates 400 billion yen from domestic publications alone. It's thought to be a 3 trillion yen industry when film adaptations and copyright sales from overseas are included," said Haruyuki Nakano, author of Theory of Manga Industry. "It's understandable that high school students want to make a career in the field.”

Universities take the demand for the subject seriously and have begun trying to attract students on that basis. Colorful illustrated pamphlets and school brochures feature phrases such as "Be a world-famous content provider!" or "We're equipped with a full-scale studio that would impress professionals." Many self-taught mangaka who carved out their own career paths as professionals are now teaching. "Manga are read around the world. I hope talented people are nurtured [in the universities] to eventually expand the horizon of manga expression," said veteran mangaka Tetsuya Chiba, who currently teaches at Bunsei University of Art in Utsunomiya.

Each university with a manga department endeavors to make its curriculum stand out by advertising the achievements of its teachers. Professionally active mangaka teach practical skills, while editors at leading publishers sometimes give guest lectures from a professional viewpoint. Gakushuin University established graduate courses for critical and practical studies on the theory of manga and animation based on the concept that "Study in the 19th century was based on texts. However, contemporary culture cannot be discussed without representation [images].”

Curriculums include such titles as "History of painting and iconography," "Literacy of expression," "Basics of space composition" and "Theory of world vision." Many universities offer classes on history, manga analysis and ideology to enhance students' creativity through systematic mastery of the subject. Mangaka Machiko Satonaka, who also is head of Osaka University of Arts' character formation department, said: "Unlike in vocational schools, university students can interact with people in other departments and broaden their way of thinking. They can also learn from many others and learn to work more efficiently.”

Unlike in other disciplines, the prestige of being a graduate from a specific university has yet to catch on with respect to graduates trying to sell their skills on the manga and anime job market. To increase the value of its graduates in the job market, Kobe Design University has published magazines featuring collections of its students' work. Called TObiO, it is issued twice a year through a publishing company for 780 yen and carries the work of a dozen students who are enrolled in or graduated from the university. Similarly, Bunsei University of Art sends its quarterly magazine, Comic Stellar, to publishing companies.

Overseas Students Studying Manga

Asako Kisui wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “With many young people aspiring to careers in the manga and anime fields, universities are offering courses to nurture the next generation of pop culture creators. The relevant curriculums are segmented or specialized, and include graphics and animation, Internet anime and manga, and character formation. From the next academic year, new courses on "gag manga" and character figures will start at some universities. [Source: Asako Kisui, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 14, 2012]

Daniela Russo, a 24-year-old Italian, first encountered shojo manga aimed at girls via an online manga browsing site when she was in high school. She was intrigued by the cute characters and the storylines centered around Japanese school life. Russo, currently in her junior year, hopes to make her debut in a Japanese comic magazine. Upon arriving in Japan and before enrolling in the university, she studied Japanese intensively for two years. "Even in black and white, I feel the color and sound in manga. It's just like watching movies," Russo said. One character she draws has big glittering eyes and wears a school uniform--a prime example of the bishojo (beautiful girls) who often appear in shojo manga.

One of Russo's classmates, Robin Lingstrom, 25, comes from Sweden. "All I see in Western comics are jokes and gags. Also, they're mostly aimed at kids. But manga, I think, should be considered an art genre," he said. Lingstrom currently practices sketching in the style of Katsushika Hokusai and dreams of becoming "a mangaka who can influence society" by taking up such themes as politics and environmental problems.

Students from Asian countries often grow up reading manga translated into their own languages. They come to Japan at a young age, with high ambitions. Natakorn Ulit, 20, came to Japan from Thailand to attend high school. He participated in a Manga Koshien, or high school manga tournament. South Korean Park So Yeon, 18, studied Japanese in Japan when she was a high school student, because "it's better to learn the language in the country where it's spoken.”

In the classroom, the students were evaluating one another's work in fluent Japanese. "The lines are fine and beautiful," one student said of her classmate's design. "What a beautiful character!" another remarked to a friend. The words in balloons are naturally written in Japanese, with kanji used appropriately. The students draw smoothly and then supply dialogue. Some international students who graduate from the university are able to make their debut in Japan. Their success, however, depends greatly on their ability. Unable to stand up to the fierce competition with Japanese mangaka, many foreign mangaka return home.

Image Sources: 1) 5) Osama Tezuka site 2) 6) 12) exorsyst blog, 3) National Museum in Tokyo, 4) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 7) 9) Hector Garcia, 8) Japan Zone, 11) Ray Kinnanae, 13) Amazon and Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013