MANGA OUTSIDE OF JAPAN

Since the early 1990s there has been a notable increase in the export of Japanese “manga”to Europe, America, and countries in Asia. In places like Taiwan, Hong Kong, and South Korea, which used to be known for their pirated editions, large numbers of the most recent popular “manga”from Japan are published in translation through formal license agreements with large Japanese publishers. In Europe and America, the popularity of broadcasts of Japanese animation on television has greatly increased interest in “manga”. Shelves lined with “manga”featuring the stories of animation series such as “Dragon Ball”(by Toriyama Akira) and “Yu-Gi- Oh!”(by Takahashi Kazuki) are now a familiar sight in U.S. bookstores. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Anime first rose to international popularity in the 1970s, and paved the way for manga in the global market. To adapt to overseas audiences, manga images were initially flipped so that readers could read from left to right. However, nowadays it's common to see manga read from right to left as it's strange to see a right-handed protagonist become a left-handed one. While the text in speech bubbles is still read from left to right, non-Japanese readers have become accustomed to reading pages right to left. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, August 17, 2012]

“In 2002, a major Japanese “manga”publisher established an overseas affiliate to market translated editions of Japanese “manga”and distribute animated “manga”. The company launched a monthly English-language edition of Shonen Jump in 2003. As of 2009, “NARUTO”, a “manga”serial in the “ Shonen Jump”magazine, in which the main character is a ninja boy, has been republished in book form and distributed in more than 30 countries. The animated version is on the air in more than 80 countries. Japanese “manga”and animation have clearly expanded beyond their original group of hardcore fans to become a significant part of Western pop culture as a whole. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Manga has been popular in the United States, Germany and France for some time. It didn’t really begin to catch on in Britain until the mid-2000s. The Internet has help spread manga around the world but has also provided alternatives to spending money on manga books and magazines. When asked why they like manga and anime American university-age students say they like the art, they get a kick from the sex and violence and they find the plots and stories refreshing and different from American ones and the characters more multi-dimensional and less superficial.

Two of the most popular comic, which have been translated into English, are “Akira” and “Lone Wolf and Cub”. Manga like “Doraemon, City Hunter” and “GTO” are popular in Asia.

Many foreign movies and television dramas have been based on Japanese manga. “A Battle of Wits”, set in the warring epoch of ancient China, is being made into a movie by Hong Kong director Jacob Cheung. The popular South Korean film “200 pound Beauty” was based on the Japanese manga “Kanna-sam Daiseoko Desu!” by Yumiko Suzuki. In Taiwan, more than 10 television dramas have been based on Japanese manga for girls. Including “Meteor Garden”.

As a sign of the extent and the talent of oversees manga fans, the Morning International Manga Competition award for best new manga artist went to a Houston-based artist who goes by the name rem for her work “Kage no Matsuri” (“Festival of Shadows”).

The Japanese government has developed a national plan to export manga,

Foreign Fans, Manga, Anime, Kawaii and Otaku Culture

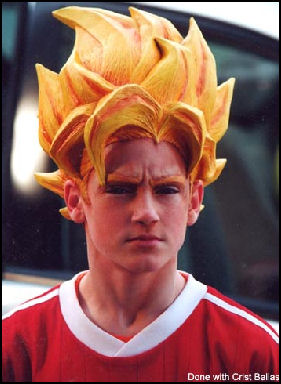

American dragonball fan Overseas you can find people who love manga, anime, kawaii and otaku culture and sometimes lump them altogether because they are Japanese and are all represented at international anime and manga festivals. Takamasa Sakurai, editor for Tokyo Kawaii Magazine, wrote in Yomiuri Shimbun: In 2008 “I realized we are amid a world kawaii revolution; I heard girls in Europe talking about how they wanted to be Japanese, or that Japanese high school uniforms symbolize freedom. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Yomiuri Shimbun, April 29, 2011]

Young people overseas search for information every day by typing keywords such as anime, manga, kawaii, Tokyo, fashion and Harajuku. In doing so, they come upon websites with information on Lolita fashion, dojinshi, fashion brands and the way to find them. Foreign youth who grew up with anime have much in common with young Japanese people when it comes to pop culture. Both groups search the Internet for information on their interests, which are often similar. If two people with shared interests can directly communicate, they initiate a type of cultural exchange, which promotes more global exchange in general. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, March 2012]

“Foreign fans of Japanese culture, in short, do not distinguish between the otaku hub of Akihabara and the street fashion hub of Harajuku, despite being quite different in the eyes of the Japanese. It is quite usual for foreigners to be interested in both Harajuku fashion and anime works such as “The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya” and “Neon Genesis Evangelion”. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Yomiuri Shimbun, April 29, 2011]

Young women I meet overseas often ask me to visit their homes because they want to show me all the Japanese stuff they have and how much they love this country. Their rooms are packed with Japanese clothing, jewelry, CDs and other products, but their computers, TVs and cell phones are all South Korean. The models on their screensavers are Japanese, the monitors they are on are South Korean.

The term "Galapagos" has recently been used in a largely negative context, referring to technology or business models that have developed uniquely in a limited environment. But this is the very uniqueness for which Japan is praised throughout the world. I think Japan should be making things only it can produce.

Takamasa Sakurai, an organizers of manga-anime events, wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “What interested me most about manga-anime fans was that they said their ideal partner would be Japanese. In everyday life, they rarely interact with Japanese, so young people in Russia chat online with each other about Japan and Japanese people in the same way they talk about Japanese anime and idols.

When talking with young people from around the world, I'm often bewildered by their glamorization of not only Japan, but also Japanese people. If even I--with my many opportunities to interact with these "Japan admirers"--am overwhelmed by the trend, then Japanese people who have never heard about it before are even more shocked. I'm often asked to talk about the question: "Are Japanese people popular overseas?" when I appear on Japanese TV or radio.

"If I can go to Japan, I'd like to gaze at men walking by on the street at a cafe in [Tokyo's] Harajuku for a whole day," a Croatian female college student told me. When I asked another female college student I met in Mexico if she was interested in going out with a Japanese boy, she replied, "Not worth asking. [Of course!]"

Studying the Popularity of Manga Overseas

Asako Kisui wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “A group of researchers on Japanese subculture are delving into the minds of people in foreign countries to discover why exports like manga and anime have become so popular overseas. Kobe University Prof. Kiyomitsu Yui, 59, a sociology expert with the Japan Subculture Studies (JSS), said, "We're in the process of discovering how Japanese subculture has become so widespread by investigating the psychology of foreign people who embrace it." [Source: Asako Kisui, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 14, 2012]

JSS, which was established in 2010 at Kobe University's school of humanities, includes researchers from various Japanese universities. The group also collaborates with professors of the Paris Institute of Political Studies, Yale University and the University of Hong Kong, and has partnered with research institutes in such countries as Italy, Poland and Mexico.

As part of its research the group conducts surveys at cosplay events in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan with financial support from the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry. Participants are asked such questions as when they first discovered cosplay--the practice of dressing as a favorite character--what media led them to it, and how their families and friends reacted to their new interest in this aspect of Japanese culture. The group then compared the results with polls done in Europe. "Some people don't look highly upon the kind of research being done by state-run universities," Yui said. "But our efforts to heighten the quality of Japan's subculture would surely lead to an increase in the number of foreigners who understand Japan today.”

Researchers from 13 countries gathered at international meetings on Japanese subculture in Kobe and Kyoto in June. One researcher gave a presentation on the fan base for animation that depicts gay sexuality called "Boys love manga." "Research on Japanese subculture is a melange--crossing into the fields of sociology, philosophy, art, literature and media studies. To deepen the roots of subculture, we must first grope for its basis," Yui said.

Manga in the United States

Manga sales in the United States topped $200 million in 2006, compared to $60 million in 2002. Japanese comics now account for 9 percent of the comic sales in the U.S. Best selling manga have a circulation of up to 5 million copies a week.

The number of titles released in 2008 was 1,700,compared to 1,008 in 2005. As of September 2006 over 40 syndicated newspaper, including the Los Angeles Times, had added manga to their funny pages.

In November 2002, English versions of two of Japan’s most popular manga magazines’shonen Jump and Coamix — were published in the United States for the American audience. By 2003, Shonen Jump had a monthly circulation of 540,000. In 2004, DC Comics introduced manga-like publication called CMX.

The dominant publishers of manga in the United States are Tokyopop and Viz. Based in Los Angeles, Tokyopop produces both translations of Japanese favorites and American originals. It is the largest U.S.-owned creator and licensor of manga, with $40 million in sales in 2005. Its books read from back to front so as not compromise the artwork and the Japanese sound effects are spelled phonetically. Tokyopop signed had a deal with Harper Collins, Simon & Schuster and Random House are also aiming to get a piece of the manga action.

Manga has become very popular with American girls and teens. About 60 percent of manga readers are females. Magazines like CosmoGirl feature works by manga artists. Many girls and young women show up in cosplay costumes at anime and manga conventions. Many got their start with Sailor Moon and moved on to harder stuff. According to some sources 90 percent of yaoi (boy-boy soft-core erotic manga) is purchased by women

Offering a theory on the success of manga in the United States, one American manga artist said, young Americans “have grown up on...video gaming like PlayStation and all that, which is very much anime-manga style art...I think [manga] appealed to them because everything else they like is in this style.”

Hollywood and American publishers arguably made more money from anime and manga in the United States than Japanese companies have.

Peach Fuzz in a manga produced by American artists. It is about a 9-year-old girl and her pet ferret Peach.

American Mangaka in Japan

Japan Expo in 2011 Roland Kelts wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Felipe Smith was born to a Jamaican father and Argentine mother in Ohio, raised in Buenos Aires, trained at the Art Institute of Chicago, and discovered while living in and creating comics about Los Angeles. At 32, he has lived in Tokyo for 2-1/2 years, publishing his series Peepo Choo (Pikachu rib-poke) first in Japanese with Kodansha Co., then in English with Vertical, Inc. [Source: Roland Kelts, Daily Yomiuri, October 29, 2010]

“It helps that he walks the walk: Smith is an autodidact who learned to speak Japanese fluently in Los Angeles via a Japanese roommate, a job in a karaoke bar, and sheer will. Now he writes at least some of his original text in the language, the rest of which is translated by Shiina. Smith discovered manga in a Japanese bookstore in Los Angeles, attracted to the size of the books and the scope and range of the stories, though he's hardly an avid fan.” "What drew me to manga was that there wasn't this template," he told Kelts. "It wasn't so much the content, but the diversity of styles. There is no single drawing style for manga. That's why I'm here. What's being sold to the rest of the world is very limited, but here [in Japan], you can do all kinds of things."

“In 2003, Smith won the "Rising Stars of Manga" contest, the brainchild of U.S. publisher and distributor TokyoPop's chief executive officer and founder, Stuart Levy. "Felipe's art really stood out," Levy recalls. "Each and every page was filled with details, from the backgrounds to the characters's facial expressions, and his line-work was polished."

TokyoPop published Smith's first series, the three-volume MBQ (which he now describes as a seinen, or young man's, manga set in Los Angeles), in 2005, garnering the attention of agent Shiina, who helped land his current editor at Kodansha. Smith's is an exceptional story, to be sure, as is the story of Peepo Choo itself — a U.S.-Japan culture clash comedy mocking and celebrating pop culture fans in both countries, drawn in riveting and sometimes surrealistically violent graphics. His achievement would seem many a foreign manga fan's dream.

“But unlike the salarymen in his adopted homeland, Smith is determined to transcend Japan's Galapagos mentality. He wants his work to be read and appreciated worldwide. "We have to get beyond these silly classifications of manga and comics, Japanese or American. The hardest thing is trying to make it a global thing, not just for the reader here, but everywhere. It's definitely possible, though, and I think it's necessary. It's just really hard."

Anime Fans in the United States

Madonna in cosplay-like outfit The 15th annual Anime Expo in the United States in 2006 attracted 55,000 fans, up from 1,750 its first year in 1992, including many who engaged in cos-play an dressed up like their favorite anime and manga characters. The event is sponsored by the nonprofit Society for the Promotion Japanese Animation. In 2009, more than 9,000 people showed up an the “Sakura Con” anime event in Seattle, twice the number as the previous year, and paid $30 to $60 to be there.

American anime fans tend to be teenagers and young adults aged 18 and 24 with a considerable number between 13 and 18 and some “tweenies” who are under 13. The fans are equally divided between males and females, with the younger groups embracing more females. The reason for this is thought to be related to the popularity of “Sailor Moon” among young girls.

The anime market in the United States is very girl driven. “Naruto”, “Bleach” and “One Piece” are more popular among girls in the United States than in Japan. “Death Note” was popular with both genders and “Gundam Wing” is thought to be more popular with American girls than boys despite its “mecha” (giant robot warrior) theme. “Escaflowne”—“a mecha-magical girl series with a lot of elements of romance” — is bigger in the United States than it is in Japan.

Iconic Japanese Baseball Anime Remade in India Featuring Cricket

In September 2012, Jiji Press reported: “The world of Kyojin no Hoshi (Star of the Giants), a famous Japanese TV anime series, will be adapted for modern-day India and feature cricket, India's favorite sport, instead of baseball. Titled Rising Star, the cricket version is jointly created by Japan's TMS Entertainment, Ltd. and Indian anime studios. While the sport is different, the storyline of a protagonist who undergoes a tough training program designed by his father to become a star player at the professional level remains the same.[Source: Jiji Press, September 7, 2012]

Titled Rising Star, the cricket version is jointly created by Japan's TMS Entertainment, Ltd. and Indian anime studios. While the sport is different, the storyline of a protagonist who undergoes a tough training program designed by his father to become a star player at the professional level remains the same.

Kyojin no Hoshi is about the life of Hyuma Hoshi, a promising baseball pitcher born into a poor family in Tokyo who strives to become a top professional ballplayer with the Yomiuri Giants under the grueling training of his father, Ittetsu. Based on a popular comic series published by Kodansha Ltd., the TV anime was aired in the 1960s and 1970s.

Similar to the original story, which is staged in Japan's post-World War II period of high economic growth, the Indian remake depicts the growth of Suraj, a boy living in a Mumbai slum who hopes to become one of the best professional cricket players. In the Indian story, Suraj's father, Shyam, is a rickshaw driver who once came close to playing for India's national cricket team. Mitsuru Hanagata, Hyuma's rival, becomes Vikram, a scion of a rich family who plays for a cricket team in New Delhi. The Indian channel will air 26 episodes, each 21 minutes long.

"Today, India is in the middle of an economic evolution that is similar to the one Japan experienced when it was in a high-growth period. Dashing sports dramas like Kyojin no Hoshi could be a relatable subject [for Indians today]," said Sam Yoshiba, an executive director of International Business Division at Kodansha Ltd., the original manga publisher of Kyojin no Hoshi. Yoshiba produces the anime adaptation project in India. [Source: Aiko Komai, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 19, 2012]

Rising Star will reportedly include familiar scenes from Kyojin no Hoshi, including a training gear similar to the Major League Training Uniform that was invented by protagonist Hyuma Hoshi's father Ittetsu to tone his muscles, as well as "magical effects" for Hyuma's pitching. Fans of the original show are also eager to see how the popular "chabudai gaeshi" scene will be adapted for Rising Star. In the scene, an irritable Ittetsu loses his temper and flips over a chabudai dinner table. "Flipping a table could be seen as violent in India. Also, it's a no-no to handle foods roughly," Yoshiba said.

Starting New Manga Magazines in China

Aiko Komai wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Kodansha and a local corporation in southern China established a joint publishing company to produce a manga magazine. Called Jin Manhua, the magazine features original stories drawn by local mangaka. Yoshiba said the magazine was launched in response to "tight restrictions on publishing Japanese manga abroad." [Source: Aiko Komai, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 19, 2012]

A dozen Kodansha staff were transferred to a Beijing office to teach Chinese mangaka Japanese editing style, which involves collaboration between mangaka and editors to develop storylines. Kodansha is also looking for talent in China by holding manga contests. An all-color comic magazine, Jin Manhua, is priced at 8 yuan (about $1.10) with a normal circulation of 300,000 copies. While the magazine operates in the red, Kodansha aims to create business opportunities by commercializing manga character goods or publishing comic books of individual series.

Elsewhere in China, Kadokawa Group Holdings Inc. established a joint venture company with a publishing group in Hunan Province for a monthly comic magazine Tian Man in September 2011. Tezuka Productions collaborated with a Beijing publisher to launch a monthly magazine that is 80 percent Osamu Tezuka works and 20 percent local manga.

Manga researcher Haruyuki Nakano says the trend has spread due to the limitations of the Japanese manga market in China. "Localization is an inseparable part of expanding business overseas. The Japanese manga industry is in a position to export not only the content, but the culture of manga itself," Nakano said.

Manga in Europe

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Many manga comics have been translated into French, English and Spanish. In Barcelona, I even found manga that had been translated into Catalan...Very girly manga Kimi ni Todoke (From Me to You) — which is about a girl who doesn't realize she's fallen in love — was popular in Italy and Spain... When I visited Geneva in May 2009, I went to a bookstore near Lake Leman called Tanigami, which boasted a stock of 11,000 manga translated into French. The shopkeeper told me he sold between 3,500 and 5,000 manga a month, or more than 100 copies per day. Some manga enjoy initial print runs of more than 100,000 copies.[Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, October 12, 2012]

And what about the language? I spoke with Simona Stanzani, who has translated Japanese manga into Italian since 1992. Originally from Bologna, Stanzani translates three to four books a month. Recently, she has worked on such titles as Bleach, Soul Eater and Kuro Shitsuji (Black Butler). "I get jobs directly from Italian publishers. In Italy, I think between 80 and 100 manga are published per month. The same series are popular in Italy as in Japan," she said.

"I have to rack my brain to come up with the right ways to translate jokes and gags popular among Japanese high school girls into Italian," Stanzani said. "I use different expressions with similar nuances, but I try not to change phrases based on Japanese culture. Instead, I add annotations." For example, when a protagonist frequently uses the "sempai" to refer to an older fellow student, Stanzani leaves the word as is but explains its meaning and nuance the first time it is used. "There's no real equivalent to sempai in Italian," she said.

To help Italian readers share the same feelings as Japanese readers, Stanzani said it's important to translate Japanese culture as well. "That's why I describe my job as 'culture translation,'" she said. Asked about what techniques she uses to translate various mimetic and onomatopoeic phrases in manga, Stanzani said, "I try to change them to something that's used similarly in our language. But, most of the time, I just translate them phonetically like, 'Kyaah,' 'Waah' and 'Uooh.'"

Manga in France

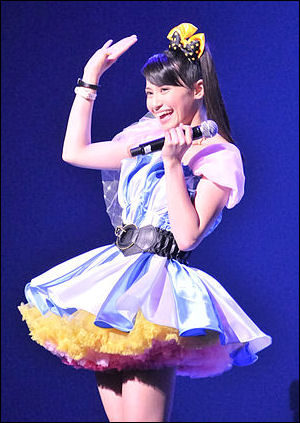

Japan Expo in 2011 Manga is very big in France, The annual Festival Internationale de la Bande Dessince is regarded as the best manga festival in the world. There are manga cafes and bookshops that specialize in manga on Paris, The ninth Japan Expo in Paris in 2008 was held in a space twice the size of the Tokyo Dome. More than 130,000 people showed up, many of the fans between the ages of 15 and 22 show in cosplay outfits, even a “Gosuu-rori” Lolita outfits.

About 40 percent of the comic books printed in France in 2009 were Japanese manga. More than 1,200 manga titles and works by 450 manga artists have been translated to French. More than 13 million manga books have been sold. “One Piece”, “Natuto” and “Dragonball” have particularly large followings. “Naruto” has sold over 7.7 million copies in 37 volumes; “Dragonball”, 19 million copies. Books stores say that around 35 percent of their comic book sales are manga. In 2006, there was a story of a 16-year-old girl who were taken into protective custody in Poland after emrbaking on an overland journey from France to the Land of Naruto. Horror manga is popular in France. Hideeshi Hino, creator of the “Hono Horror” series is particularly popular. He was been called “the grandfather of contemporary horror manga.”

Shinya Machida wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The recent manga boom in France is reminiscent of Japonism--the period when ukiyo-e from the Edo period (1603-1867) greatly influenced French art. At Salon du livre de Paris, France's largest book fair... I saw children wearing masks of characters from the popular ninja manga Naruto written by Masashi Kishimoto and published by Shueisha Inc. The manga's local distributor had set up a booth and was handing out the masks to visitors for free. According to Shueisha, France is the company's largest market outside Japan. Dragon Ball grew in popularity from around 1995, and Naruto was introduced in 2002. From December 2010 to November 2011, Naruto sold 1.22 million copies and One Piece has sold 1.42 million. [Source: Shinya Machida, Yomiuri Shimbun, May 4, 2012]

The Manga Cafe stands near the prestigious Paris-Sorbonne University. Opened in 2006, it houses about 12,000 manga in a space measuring just 100 square meters. Visitors can read manga at the cafe for about 3 euros-4 euros (300-400 yen) an hour. "The characters in Naruto are appealing, and the manga is filled with fight scenes," said a student at the cafe. "In Death Note, I learned about life and death.”

"Manga is artistic because the story, characters and atmosphere are all captured in one panel," said Boris Tissot, organizer of Planete Manga! (Planet Manga), a manga event for young people held at the Centre Pompidou. Another Paris street is crowded with stores specializing in Japanese manga and figurines of characters such as Dragon Ball's Kame Sennin (known in English as Master Roshi) and PreCure. A costume shop there displays a signboard reading "cosplay.”

According to Jean-Marie Bouissou of the Paris Institute of Political Studies, France is the largest importer of Japanese manga. “These days, young people don't believe French culture is special. They don't care about the origins of whatever culture they enjoy. They don't have a particular enthusiasm for being and celebrating things French," the 60-year-old professor explained. [Source: Tetsuya Tsuruhara, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 13, 2010]

Books by French novelists whose writing is heavily focused on Japan are also drawing attention. One of the these is “Sympathie Pour le Fantome” (“Sympathy for the Phantom”) by Michael Ferrier, 43, who teaches at Chuo University in Japan. Ferrier first arrived in Japan in 1992 and has lived in the country almost the entire time since then. He has published three novels, all of which are set in Japan.

Explaining the reasoning behind setting his books in Japan, Ferrier told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "Due to globalization, societies around the world have undergone rapid change. People from different backgrounds are increasingly mixing together. People are asking: 'What does it mean to be French?' Of course there have been misunderstandings, but Japan has a long history of successfully dealing with different cultures. Through Japan, it is possible for me to think about identity."

Ferrier also explained about French people's interest in Japan, now especially represented by a strong fascination with manga. "It is not a fad. It is a deep, driven interest. Something is shifting in French society," he said. The average age of French people reading Japanese manga is said to be 22 to 23. One survey found that 15 percent of these people would like to work in Japan in the future.

Despite all this In France manga sometimes gets a bad rap. Art historian and manga expert Brigette Koyama-Richard told the Daily Yomiuri, “In France, there are as many people who hate manga as like it, They automatically link manga with violence and sex, without reading it.”

”BD” — French Manga

Shinya Machida wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “In France, there are also locally produced graphic novels called "bande dessinee" or BD. Wandering around bookstores, I found some eccentric and adult BDs, one based on the erotic novels of the Marquis de Sade. There was also Marjan Satrapi's Embroideries, which openly depicts the love and marriage of an Iranian woman. [Source: Shinya Machida, Yomiuri Shimbun, May 4, 2012]

Many BD artists have been influenced by Japanese art, including Jean David Morvan, 42. Morvan was among the first generation of French children who grew up with Japanese manga. He began watching anime such as Candy Candy and Space Pirate Captain Herlock when he was 6 years old. During that time, many new anime and manga, such as Dragon Ball and Maison Ikkoku were released in rapid succession.

Morvan said he was fascinated by manga's "dual nature." Although the stories often took place in Japan--an exotic setting for French readers--they also dealt with universal issues such as love and marriage."I want Japanese people to pick up French comics. Not all of them are high-end, though," he said.

The French artist Moebius is regarded as a master of French bande dessinee comics. Japanese mangaka Katsuhiro Otomo, the creator of Akira, reportedly said Japanese graphic novels are drawn with force, and the lines are thick. But Moebius' lines don't have such strength and are uniform in every stroke. Otomo imagines that Moebius perceived things objectively and quietly. Moebius' works including L'Incal (The Incal), 40 days dans le desert B and Le Monde d'Edena have been translated into Japanese. Kanta Ishida wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: There are contrasts between Japanese and French masters of manga. Moebius' touch is rather soft and alive, while Otomo's lines are dry and hard, with a feeling of coldness.” [Source: Kanta Ishida, Daily Yomiuri, May 4, 2012]

Anime in the Middle East

Takamasa Sakurai wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: In March 2008, I was invited to give an anime lecture at a book fair in Riyadh. In Saudi Arabia, men and women were not allowed to listen to my lecture in the same room. I could not see the faces of the female audience members, who were watching me on a big screen in the next room. Whenever I mentioned Naruto or One Piece, I heard shrill voices from the female group through a gap in the partition. Their passion shocked participating Japanese diplomats. [Source: Takamasa Sakurai, Daily Yomiuri, April 12, 2012]

Four years after my visit to Riyadh, I got the chance to go back to the Middle East to give a keynote lecture at an international symposium titled "Dialogue for the Future between Japan and the Islamic World" held in Amman by the Japanese Foreign Ministry. My topic was "How Youth Culture will Change the World." In front of 150 scholars and students, I talked about how Japanese pop culture has influenced young people overseas, and how this trend can have a positive impact on our shared international future as members of a global community.

Many Islamic scholars who might have been unfamiliar with the subject ardently listened to me and expressed favorable reactions after the speech. I also felt that the Japanese diplomats' attitude toward anime diplomacy had changed since the 2008 event. In the past any organized, session featuring discussions with experts in the field was regarded as minor. But the fact that I delivered this keynote speech at a state-organized symposium served as proof that these topics were important--thanks to people around the world who are passionate about Japanese pop culture.

One of the symposium attendants was Emi Kato of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, another organizer of the event. She studied Arabic at Jordan University and was in the audience during my 2008 lecture, when she worked as a researcher for the Japanese Embassy in Saudi Arabia. "I felt the [recent] symposium was meaningful because in addition to debate and discussion among experts, young people, who will forge the future of the world, also gave speeches, joined in debates and interacted with experts of all ages," Kato said.

The day before the symposium, Kato introduced me to Jordan University students who were learning Japanese. About 20 students welcomed me and five Japanese students, who were chosen to attend the symposium in Amman, with homemade sweets and other dishes. The students introduced themselves and eagerly shared their interests. Jordanian students said they were into manga such as Bleach and Naruto or idol groups including News and Morning Musume.Interpersonal exchange is just as important as symposiums or formal events, as such personal connections can be enhanced through networking sites like Twitter and Facebook.

After the symposium, the Japanese students and I visited the house of a local family. One of the family's sons had learned Japanese from Kato and is a big fan of Gintama, a manga and anime series that is very popular in China. The son spoke about his favorite anime the same way as Gintama fans in China do.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, Daily Yomiuri, Japan Times, Mainichi Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013