KAYOKYOKU AND ENKA

“Kayokyoku” is a form of Japanese popular music popular enjoyed mostly by people over 40. Based on the scales of Japanese classical music, it emerged after World War II as a synthesis of traditional Japanese music with imported music like big band jazz, Hawaiian music, American country-and-western and rhythm and blues.

“Enka” is a style of music, also popular with older people. Similar to kayokyoku except that it incorporates the scales of Western music and sometimes called the country-and-western music of Japan, it features sobbing vibrato-style “kobushi” singing, syrupy string arrangements, and sentimental lyrics. The word enka is derived from “en” (a short form of “enzestu”, meaning public speech) and “ka” ("song").

Female enka singers usually appear in a kimono. The male singer often have greasy hair and sequined suits and look like Japanese version of lounge singers.

History of Enka and the Origins of Popular Music in Japan

In the first half of the 20th century, Western influence on Japanese popular music gradually grew. However, while Western instruments came to be widely used, either exclusively or in combination with native instruments, melodies were still based on the Japanese pentatonic scale. The earliest commercial phonograph records in Japan date from 1907, and during the 1920s an increasing amount of popular music was recorded.

“the 1930s jazz played a significant role developing a popular music scene in bars and clubs. Although it was banned in World War II, since then jazz has continued to have a relatively small but dedicated group of fans and native performers, some of whom (Watanabe Sadao, Akiyoshi Toshiko, etc.) are famous internationally. In the postwar era, Japanese popular music has followed two distinct paths: one being J-Pop, the other being “ enka”.

In 1874, Japan’s first political party was founded, and the call for direct election of a national parliament gained strength. Leaders, who were often prohibited from speaking in public, had songs written to air their message and singers walked the streets selling copies of the songs. This was the beginning of “ enka”. The performers themselves gradually developed from street-corner political agitators into purveyors of sheet music and paid professional singers. Before the spread of radio and phonographs the “ enka “singers were an important medium for the publication of music. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Unlike the political “ enka “of the Meiji period, modern enka “ballads are concerned almost exclusively with lost love and nostalgia. Its most distinctive feature being the slow vibrato in which melodies are sung, “ enka “continues to be very popular among Japan’s older generation and is a mainstay of karaoke “playlists.

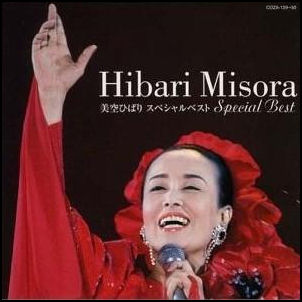

“San-nin Musume" (Three major female idols) were the idols of the 1950s and 60s. They were Chiemi Eri, Izumi Yukimura and Hibari Misora. After that, there were many three- or five-member idol groups.

Enka Songs

Most enka songs are about longing for home, enduring hard times, lost love, rainy weather and drinking. Many of them feature men as masters and woman as fragile things, devoted servants to their men. The song “Kita no Yado” ("Northern Inn") is about a woman knitting a sweater for a man who has left her. The lyrics go "It must be my heart/ Unable to give up and let you go/ I miss you so, in this northern inn." [Source: Kaori Shoji, Japan Times, February 9, 2001]

“Tsugaru Kaikyo Fugugeshiki” ("Winter Season on the Tsugaru Strait") is one of the most famous enka songs. It is about a heartbroken, abandoned woman who takes a ferry back to her home town and is surrounded by depressed people on the deck of the ship. The lyrics go: "Goodbye my love, I'm going home/ I look out at the freezing seagulls and weep."

In “Funauta” ("Fishing Boat Song") a woman sings about the things she should provide her man: "Sake must be lukewarm/ The woman who pour its must be quiet/ And when I am with him the light should be subdued." “Showa Karesusuki” ("Wither Grass in the Showa Era) is a classic enka poverty song. It goes: "Poverty broke me/ No, the harsh world has broke us/ This town is over use/ So, what do you say, we both just die."

Misora Hibara

The most popular kayokyoku and enka singer was Misora Hibara, a beautiful singer-actress who emerged in 1949 at the age of 12 and remained popular until her death in 1989. In addition to being a popular singer she was the queen of cheerful Japanese B-movies like “Tokyo Kid, Three Girls” and “Growing Up” in the 1950s and 60s.

Known for her versatility, she continues to sell hundreds of thousands of recordings a year. Her most popular songs included “Yawara” (1964), “Ai san san” (1986) and “Kawa no nagre no yoo ni” (“Like the Flowering River” 1989).

Misora worked hard and made lots of money. She recorded over 1,200 songs and 675 albums and at her peak appeared in a new movie almost every month. She sold millions of record and was listed high on Japan's list of highest tax payers for many years in a row.

Misora’s fame also had a dark side. At one public appearance a fan was crushed to death when the crowd rushed forward. Another time an envious fan threw acid in her face. After that she sought protection from the yakuza and for that she was shunned by the media and her popularity declined. She didn't make a come back until it was widely known that she had a serious disease.

Misora performed a famous concert at the Tokyo Dome a few months before she died from hepatitis and gangrene, receiving constant injections of painkillers to get through the show.

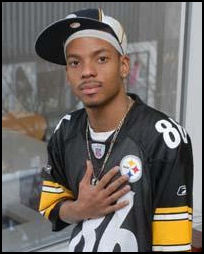

Jero, the African-American Enka Singer

Jero, an African-American from Pittsburgh who dresses like a hip hop star and sings with perfect Japanese pronunciation and a melancholy soulfulness, has been a big enka — and pop music’sensation in Japan in the late 2000s.John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “He's a Japanese pop music marvel. With his smooth voice and street stylings, he's helped revitalize a once-popular enka genre, which he likens to the American blues, whose popularity had fallen on hard times. His sold-out concerts are packed with teenagers who consider him a new cult figure. Among the young hipsters are the white-haired retirees, old women on hand for a sentimental evening of nostalgia for a Japan that no longer exists.” [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 2011]

In December 2008 he fulfilled his dream by singing on the NHK red-and-white New Year show. Jero was the top-selling enka singer in Japan in 2008. He was one of the top 10 artist that year and had hit with the classic enka songs Hiusame. His debut single “ Umiyuki “ (“Ocean Snow”) made it to No. 4 on the Japanese pop music charts in under a week — the best-ever performance for a debut enka song — and attracted many new listeners to enka. A 17-year-old high school student who bought the single told the Daily Yomiuri, “I’d never listened to enka before “cause I thought it was uncool. But since I listened to Jero singing on TV, I’ve wanted to know more about enka and enka songs.”

Jero’s Life

Jero’s real name is Jerome White Jr. Known as Rome to his friends back home, he is the son of an African-American father and half black and half Japanese mother. He was introduced to enka by his beloved Japanese grandmother who had only a fifth grade education and came to Pittsburgh after marrying an American serviceman.

Jero sang enka songs as child without knowing what the words meant. John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “In the early 1990s, Jerome White Jr. was a skinny mixed-race kid — three-quarters African American, one-quarter Japanese — who found respite from the tough streets of Pittsburgh's North Side in the mysterious music that emanated from his grandmother's living room. “It was in the background ever since I can remember,” he says.” “As rap music blared from car radios outside, White reveled in nostalgic foreign-language songs from post-World War II Japan, painful tales of lost love and quaint, longed-for hometowns. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 2011]

White studied Japanese as a teen and visited here twice while in high school and college. Jero came to Japan for the first time when he was 14 and came to live there after graduating from college in 2003, working in information technology and as an English teacher, and calling his grandmother once a week. . In 2005 he was discovered by a record company after placing second in an amateur singing contest.

Jero didn’t have any problems adapting to Japan, where blacks are few in number and stick out when they are present. H is fluency in Japanese helped him break the ice with strangers. He also felt at home in a country where American-style rap music has become popular.

Jero and His Grandmother

Together, White and his grandmother Takiko watched videotapes of a Japanese variety show that featured the popular musical acts of the day, including enka performers.” That's when the young boy made his grandmother a promise: One day, he was going to go to Japan and become a cross-cultural sensation, singing enka songs to wildly appreciative audience.” [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 2011]

Singing enka as a boy made his grandmother happy, he told the Los Angeles Times and that “kept him singing. She bought a karaoke machine so the boy could practice and would sit by and watch him perform, correcting nuances in his fledgling Japanese. She'd write out simplified versions of Japanese kanji and characters so he could better understand the melodies.

Unfortunately his grandmother died of cancer at age 75 that year and never got to see his successful debut as an enka singer. The irony plays out bittersweet, like the enka songs that often bring his audiences to tears. "I really feel it was her doing," he told the Los Angeles Times. "She was the source of my success."

The last time White saw his grandmother was two weeks before she died. She was home in Pittsburgh, still telling jokes, deflecting the attention, keeping things light. "I knew it might be the last time I'd see her," White recalls. "I just said goodbye, like I would any other time." When appeared on the "Red and White Song Battle” his mother in the audience and he wore a T-shirt bearing his grandmother's image. He said a prayer, asking her to watch over him. "I wanted her to be there that night," he said. "And she was. My whole family was there." Jero told the Los Angeles Times he still resists focusing on the audience during his sad songs, knowing he'll see women his grandmother's age, in tears, just like she would be. It's just too painful, he says.

Jero’s Music

Jero is known for his sincerity and earnestness. On enka, he told the Daily Yomiuri, “I don’t think it is that hard to understand. There are a lot of enka songs. I think it is human nature to feel that way in many enka songs — not because enka is Japanese, but I think as a human any human being can feel this way.” [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, February 27, 2011]

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “But the kid from Pittsburgh does it his way. While fluent in Japanese, White forsakes the traditional kimonos worn by many enka singers, instead performing in hip-hop-styled street clothes, the crooked caps and thick-necklace bling of his childhood. And yet his lonesome country ballads are all old-school — the contrast evoking descriptions of White as a bizarre blend of Lil Wayne and Wayne Newton.”

Jero released a collection of enka songs from his childhood, including the first ballad he sang to his grandmother. During a recent interview, Glionna wrote, he sang a few lines of the song, about the loss of a loved one. When he finished, there were tears in his eyes.

Other Enka Singers

The chubby, dumpy-looking enka singer Yoshimi Tendo became popular in the 1990s by imitating Hibari's songs and attracted a large following of teenagers who identify with her insecurities about her looks and weight and believed a key chain with her image on it brought good luck.

Among the most popular enka composers are Shimpei Nakayama, Masao Koga and Sen Masao. Other popular singers over the years have included Miyako Harumi, Hiroshi Itsuki, Fuyumi Sakamoto and Kitajima Saburo. Songs by these people are fixtures of Japanese karaokes.

Kiyoshi Hikawa, a young man from Kyushu, became popular in the early 2000s. Although was credited with attracting young people to enka he was primarily a heartthrob for grandmothers. For many he is best known for his silly hairstyle, strange hip-swaying dancing and ridiculous clothes, particularly his ruffled shirts and candy stripe suits.

Jero

Jero, an African-American from Pittsburgh who dressed like a hip hop star and sings with perfect Japanese pronunciation and a melancholy soulfulness, was a big enka — and pop music’sensation in Japan in the late 2000s.

J In December 2008 he fulfilled his dream by singing on the NHK red-and-white New Year show. Jero was the top-selling enka singer in Japan in 2008. He was one of the top 10 artist that year and had hits with the classic enka songs “ Hiusame” and his debut single, “Umiyuki” (“Ocean Snow”), which made it to No. 4 o the pop music charts and attracted many new listeners to enka. A 17-year-old high school student who bought the single told the Daily Yomiuri, “I’d never listened to enka before “cause I thought it was uncool. But since I listened to Jero singing on TV, I’ve wanted to know more about enka and enka songs.”

Jero’s real name is Jerome White Jr. Known as Rome to his friends back home, he is the son of an African-American father and half black and half Japanese mother. He was introduced to enka by his beloved Japanese grandmother who came to Pittsburgh after marrying an American serviceman.

Jero sang enka songs as child without knowing what the words meant. He came to Japan for the first time when he was 14 and came to live there after graduating from college, working in information technology and as an English teacher. In 2006 he was discovered by a record company after placing second in an amateur singing contest. Unfortunately his grandmother died that year and never got to see his successful debut as an enka singer.

Jero is known for his sincerity and earnestness. On enka, he told the Daily Yomiuri, “I don’t think it is that hard to understand. There are a lot of enka songs. I think it is human nature to feel that way in many enka songs — not because enka is Japanese, but I think as a human any human being can feel this way.”

Saori Yuki, Pink Martini and the Kayokyoku Revival

Jin Kiyokawa wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Kayokyoku — Japanese pop songs that were hits in the Showa era (1926-1989), particularly after World War II — are finding a growing audience among people who enjoy taking a walk down memory lane. And with several contemporary J-pop artists covering these songs, their popularity also could grow in the future. The renaissance of kayokyoku has been triggered by Saori Yuki's album 1969, a collection of popular songs from that year. 1969, which features the U.S. jazz orchestra band Pink Martini, has sold about 300,000 copies since its release in October 2011. [Source: Jin Kiyokawa, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 16, 2012]

“Kayokyoku, the new album by J-pop singer Yo Hitoto, was released in April by For Life Music Entertainment, Inc., and is likely to follow the success of 1969. Hitoto has been singing kayokyoku for a long time. In Kayokyoku, Hitoto covers a range of songs including Naomi Chiaki's "Kassai" (Cheers), which was released in 1972, and Mari Sono's "Aitakute Aitakute" (I just want to meet you), released in 1966. The album has ranked 10th on the Oricon chart.

“Hideaki Tokunaga, who has released four albums featuring songs by female J-pop singers, released an album Vocalist Vintage on May 30 through Universal Music Japan, in which he covers songs such as Mieko Hirota's 1969 hit "Ningyo no Ie" (Doll's house) and Mina Aoe's "Isezakicho Blues," released in 1968.

“Songs produced by songwriter Jun Hashimoto and composer Kyohei Tsutsumi, a couple famous in the Showa era for producing popular songs, are also finding a receptive audience. The album, Mayonaka no Bossa Nova, Hashimoto Jun & Tsutsumi Kyohei Golden Album--Around 1969 (Midnight Bossa Nova, Jun Hashimoto's & Kyohei Tsutsumi's Golden Album--Around 1969), features the song "Mayonaka no Bossa Nova," which was released in 1969 as a b-side of a single by the duo Hide and Rosanna. The song's popularity surged again after it was covered in Yuki's 1969 album.

“Pink Martini member Thomas Lauderdale selected the song," 1969 album producer Go Sato said. "Though I'm knowledgeable about kayokyoku, none of us Japanese staff involved in the album knew the song." Sato's experience in creating 1969 inspired him to produce the double album so he could help reevaluate overlooked kayokyoku music. He selected songs such as Bread & Butter's 1969 track "Kizudarake no Karuizawa" (Heartbreak in Karuizawa) and Miki Hirayama's 1971 piece "Bun Bun.”

Another group from that era was The Crazy Cats is legendary comic jazz band in Japan popular in the 1960s and early 1970s. Senri Sakurai, a member of the group who died in 2012 at the age of 86, was born in London and started his career as jazz pianist while he was a student at Waseda University. After dropping out of school, Sakurai joined a band led by comedian and jazz musician Frankie Sakai before becoming a member of the Crazy Cats. [Source: Jiji Press, November 13, 2012]

Saori Yuki

Jin Kiyokawa wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: Saori Yuki’s album 1969 has taken off overseas, soaring to No. 1 on iTunes' U.S. jazz chart. With almost 200,000 copies sold in Japan as well, the album features 1969 hit songs, such as Yuki's debut song, "Yoake no Scat" (Scat at dawn), and covers of "Blue Light Yokohama" by Ayumi Ishida and "Iijanaino Shiawasenaraba" (It's OK if I'm happy) by Naomi Sagara, and is backed by U.S. jazz orchestra band Pink Martini. [Source: Jin Kiyokawa, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 2, 2012]

No one is more surprised than Yuki at her sudden overseas popularity. "I've also been singing children's songs, but I wanted to revive my career as a kayokyoku [pop song] singer who focuses on the strong emotions in our hearts. I never imagined my songs would be heard overseas," Yuki said.Generally speaking, kayokyoku refers to songs that were popular during the Showa era (1926-1989), mainly after the end of World War II.

Yuki received a standing ovation after a concert at London's Royal Albert Hall in October. She also earned acclaim through concerts in the United States in December. U.S. audience members praised her voice, posture and general manner during her performance. Some said the Japanese lyrics sounded beautiful. Others said that although they could not understand the meaning of the lyrics, they could feel the emotion in them.

Yuki's relationship with Pink Martini began when Thomas Lauderdale, the jazz orchestra's leader, bought a single of Yuki's "Yoake no Scat" about 10 years ago at a used record shop in the United States. Pink Martini performed a cover of her single "Ta Ya Tan," which Yuki saw on a video-sharing website. After that, Yuki sought out Pink Martini to collaborate on the album.

At first, only Japanese songs were selected for the album. However, Lauderdale wondered why Yuki was limiting herself to Japanese songs. He also said that although the jazz orchestra had toured all over the world, he had never heard a voice like Yuki's. At his suggestion, one-third of the album featured Western songs sung in Japanese.

When asked about the charm of kayokyoku around 1969, Yuki said: "The essence of popular foreign songs across various styles, such as canzone, chanson, blues and rock, were really integrated in kayokyoku. Not to mention the rhythmic fusion created by Japanese lyrics. Japanese harmonized well with the music, and as a result, a unique world perspective was formed and kayokyoku became hit songs."

On Yuki's success overseas, music critic Issei Tomizawa told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "In Europe and the United States, the appeal of artists like Mariah Carey is their wide vocal range and belting ability. But a more crooning, transparent vocal style, such as Yuki's, can't be heard in these countries." Tomizawa also noted that with the support of a strong arrangement from Pink Martini, Yuki's vocal style and beautiful Japanese lyrics also lead to her hits.

Image Sources: 1) British Museum 2) 4) 5) 6) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 3) JNTO4) 7), 8) Ray Kinnane 9) Libaray of Congress, 10, 11), 12) 13) Japan Zone

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2012