JAPANESE CALLIGRAPHY

Classical Japanese calligraphy is known as “sho” or “shodo” ("the way of writing"). Practiced through the centuries by samurai. nobles and ordinary people, it is both something that elementary school children take in after-school classes and an art form that takes decades to master. According to some estimates, around 20 million Japanese practice the art.

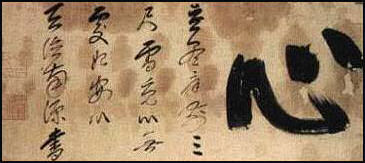

Calligraphy is a system of aesthetic Chinese writing expressed through a variety of brush movements and compositions of dots and strokes. Largely unintelligible to Westerns, calligraphy is regarded by many Chinese and Japanese as "the supreme art form” higher than painting and sculpture and more able to express lofty thoughts and feelings than words.

Fusing poetry, literature and painting into one art form, good calligraphy possesses rhythm, emotion, aesthetic, beauty, spirituality and, perhaps most importantly, the character of the calligrapher. One ancient Chinese historian wrote: "calligraphy is like images without form, music without sound."

Alida Becker wrote in the New York Times, “In the Japanese art of sumi-e, strokes of ink are brushed across sheets of rice paper, the play of light and dark capturing not just images but sensations, not just surfaces but the essence of what lies within. Simplicity of line is prized, extraneous detail discouraged.

One calligraphy artist told the Daily Yomiuri, “I love expressing the meanings of the characters and words through calligraphy in all its various forms...Calligraphy is not about writing beautiful characters, but instead putting on paper words or characters have presence and grace. Otherwise they’re; meaningless.”

See China, Art, Calligraphy

Calligraphy, History and Culture in Japan

From an early age Japanese and Chinese children are taught that calligraphy and beautiful handwriting are considered a reflection of their character and personality. Rendered in quick fluid strokes calligraphy is more concerned with flow and felling that skill deal and precision and is supposed to come straight from the heart. The characters themselves are a kind of poetry. To produce great works calligraphers must tap into the forces of qi, which many Asians believe permeate nature and the universe.

Calligraphy has traditionally been highly valued in the Japanese court. For noblemen it was one of the most important skills they were expected to master.

Japanese calligraphy is based on Chinese characters, known in Japanese as “kanji”. In the Heian period (794-1185), “hirgana”, Japanese sounds written with Chinese characters, evolved. Members of the Imperial court used it to create uniquely Japanese styles of calligraphy that was more slender, fluid and elegant than Chinese calligraphic scripts.

Calligraphy Tools, Paper and Techniques

Calligraphy requires a fude brush, sumi ink, a suzuri inkwell, hanshi paper, a shitajiki felt pad and a bunchin paperweight. They each come in several varieties and price ranges; Kinoshita recommends visiting a calligraphy speciality shop for advice on which tools you should use for your purposes and budget. Inkwells and water droppers in particular are available in many beautiful choices, so it could be fun to build an attractive collection as your skills grow. [Source: Naoko Moriya, Yomiuri Shimbun , October 22, 2010]

There are two ways to hold a brush: With the tankoho method, the brush is held like a pencil, with the thumb, index finger and middle finger. With the sokoho style, the ring finger is added.

As a specialist in kanji calligraphy, Kinoshita — who works under the name of Shusui Kinoshita — uses white paper for her work. But she uses letter paper made for brush writing when sending a letter to her friends and acquaintances. Says Kinoshita: "It can also be fun to base your choice of letter paper on the recipient and the season." There is a large selection of beautiful paper available for use in hiragana calligraphy. They come in different colors; some are patterned and some are gilded. This type of paper is called ryoshi and is believed to have originated in high society during the Heian period.

Calligraphy Tools, See Painting Materials Above

Styles of Calligraphy in Japan

There are three main styles of Japanese calligraphy: 1) “kaisho” (“block style”), the most common style; 2) “gyosho” (“running hand style”), a semi-cursive style; and 3) “sosho” (“grass hand”), a flowing, graceful cursive style.

Most Japanese calligraphers have traditionally been trained in both Chinese and Japanese scripts. The style and script employed by a calligrapher has been influenced by both the content of the text and aesthetic considerations. The most famous Chinese-style calligrapher is Kusakabe Meikaku.

Students who learn calligraphy are taught the importance of proper breathing as students of the martial arts and Zen meditation are. Longtime resident of Japan, John David Morely said calligraphy was like Sumo wresting because the calligrapher has only one brief chance to get it right.

Some Japanese calligraphy artists use tatami-size sheet fo hansh paper and gigantic brushes, the artist Choso Yabe us a brushes the size of a mops ad and paper the size of a ;large meeting room.

Comeback of Calligraphy

Calligraphy is making a comeback in primary school as a way to generate interest in traditional culture, teach etiquette and instill discipline. It is also being sought out by adults of all ages and walks of life as a means achieving a degree of tranquility and inner peace.

Calligrapher Mariko Kinoshita told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “One of the most appealing aspects of calligraphy is its meditative quality: You can reflect on yourself and feel a sense of serenity as you practice. You don't have to spend hours doing it,. For example, if you just write on one sheet of paper before heading off to bed, it will give you a sense of composure, especially if you have a rather hectic life." [Source: Naoko Moriya, Yomiuri Shimbun , October 22, 2010]

Kinoshita, who teaches the art at a culture center inside Printemps Ginza in Tokyo, began studying calligraphy privately when she was 6. She says she finds joy in reaffirming to herself the beauty of the characters and the years it took for the forms to become complete. Kinoshita told the Yomiuri Shimbun her students tend to be women in their 20s-30s. Some of them are hoping to have attractive writing; others are interested in what is known as art calligraphy, a recent movement in which there is more freedom in the writing of characters. [Source: Naoko Moriya, Yomiuri Shimbun , October 22, 2010]

“Kinoshita recommends that people new to the tradition begin by first practicing brushing the Chinese and Japanese classics, known as rinsho,” Naoko Moriya wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun. “Demonstrating her point, Kinoshita writes six kanji characters on hanshi paper. She sits with her back straight as she holds her brush, creating a tense, serious atmosphere. The six characters are from Kyuseikyu reisenmei, a Chinese classic often used to illustrate the kaisho standard, or square writing. The words are inscribed on a monument built to celebrate the coming of spring at Kyuseikyu, a palace building from the Tang Dynasty in China. Kinoshita said it is always the first thing she has her students learn.”"By meditating on why the ancient peoples left these characters, I feel as if I can get a sense of those days," Kinoshita said.

Big-Brush Calligraphy Performance in Japan

Ryuzo Suzuki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Dressed in hakama skirts, female students dip giant, oversized brushes into buckets containing various colors of water-based paints as a popular song begins to play in the background. "Let's go!" one of the girls shouts, thrusting her brush downward. Then, in sync with the rhythm, the students begin to write out the lyrics of the song being played. Such new wave calligraphy performances have started to gain widespread attention. [Source: Ryuzo Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, December 22, 2012]

Teacher Hiroko Ishiwara first introduced the idea of public performances to her calligraphy club at Saitama Prefectural Matsuyama Girls High School in Higashi-Matsuyama about 10 years ago. "I wanted to overturn the preconception that calligraphy is low-key. My goal is to make as many people understand that calligraphy is an extraordinarily beautiful aspect of Japanese culture," Ishiwara said.

Club members practice more than three hours on weekdays and eight hours on weekends. They give public performances several times a year. This year, the club even delivered a performance at a send-off party for the Japanese delegation to the London Olympics. On November 18, 2012, the club performed in front of an audience of about 600 at Okegawa City Arts Theatre in the prefecture. The girls used beautiful brush strokes to write words in Japanese and English. The expressions included words such as "thank you," "dream," and four-character compounds such as "spring, summer, autumn and winter.”

A wide range of music was used to accompany the performance, from the shamisen tune "Kami no Mai" (The dance of the paper) to "Wa ni Natte Odoro" (Let's form a circle and dance) by all-male idol group Human. After the performance drew applause from the crowd, the club's performance captain, Natsumi Sugawara, proudly said: "Our motto is to be gracious, humble and first-rate. Our goal is to deliver a dynamic performance with an inner strength that expresses the subtlety of feminine beauty and true passion of the heart.”

The club also emphasizes the fundamentals of traditional calligraphy, devoting half of its yearly activities to practicing kana moji, the unique Japanese syllabary developed in the Heian period (794-1192). In a nationwide traditional calligraphy competition, the club took first place in the group category in school year 2009 and 2011. Tsumugi Maruyama, the club's leader, explained the difference between performance calligraphy, which is usually done in groups, and traditional calligraphy, which is done by individuals. "In performance calligraphy, we feel united in spirit during performances, and we can enjoy its dynamic nature. On the other hand, we also need to reflect on ourselves individually in solitude as in traditional calligraphy. Both are wonderful in different ways," Maruyama said.

New-wave calligraphy performances are said to have first started at a high school in Fukuoka Prefecture. Many schools across the nation adopted the practice after a film and TV drama featuring such performances were aired. The number of schools participating in the Zenkoku Koko Shodo Pafomansu Senshuken Taikai (National high school calligraphy performance championships) has been growing rapidly since it was established four years ago in Shikoku-Chuo, Ehime Prefecture.

Robot Replicates Calligrapher's Work

In September 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A robot that can duplicate hand-written calligraphy has been developed by Seiichiro Katsura, an associate professor at Keio University. For the robot to copy the work, a calligrapher writes using a brush attached to the robot, allowing the robot to record information about the movement of the brush, including its angle and pressure. The robot's sensors take readings 10,000 times a second. Then the robot can recreate the brushwork using the information. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 29, 2012]

In an experiment, the robot was able to flawlessly recreated the kanji for a flower written in grass script by calligrapher Juho Sado, 89. Looking at the work, Sado was surprised and said, "It's like the brush is alive." Katsura said "It was difficult to record and duplicate the writing pressure. By using this system, we can effectively learn the skills of a calligrapher, which previously had only been available through experience and intuition.

Image Sources: National Museum of Tokyo, British Museum, Onmark productions.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013