JAPANESE DOLLS

Kyoto Hina dolls Dollmaking has been an important art form in Japan since ancient times when clay figures were buried with the dead. In the Yamamoto Period (A.D. 300 to 592) hundred of clay figures were buried around the burial mounds (“kofun”) of emperors and noblemen.

Dolls have traditionally been associated with good fortune. In the 9th century, "Japanese dolls made of paper and grass were set adrift in rivers to carry away" bad luck.

Daruma dolls are red, round dolls named after Daruma (Bodhidarma), the founder of Zen Buddhism. They commonly sold around New Year with both eyes painted over. One eye is unpainted when making a wish. The second eye is unpainted when the wish comes true.

Daruma dolls have wide open eyes and fierce scowl that are intended to keep evil spirits and demons away and bring good luck. They have no legs because Daruma sat so long in meditation that his legs fell off. Daruma himself is featured in both 15th century paintings and 21st century television cartoons. Daruma dolls with yak hair beards were popular in 2009

Dolls are featured prominently in two important Japanese holidays: 1) the Doll Festival on March 3, in which displays of dolls are set in homes with little girls; and 2) Children's Day on May 5th, in which doll displays are set up for both boys and girls.

Kinds of Japanese Dolls

In addition to daruma dolls, other well-known kinds of dolls include “gosho-ninyo” dolls, chunky plaster figures sometimes dressed like no actors; “kyoningyo” dolls, elaborate and fabulously expensive dolls made in Kyoto and dressed in brocaded fabrics; “kikuningyo” dolls, large dolls covered with real chrysanthemum flowers; and “isho-ningyo” dolls, costumed dolls often modeled after kabuki characters.

Karakuri ningyo, Japanese traditional clockwork dolls, are a specialty of the Nagoya area. They are quite lovely and can do things like draw a bow, spin a top, and or do a hand stand. One doll with collect a tea cup. The weight of the cup unlocks a spring, triggering he doll to turn and scoot along, carrying the cup to a guest. [Source: Daily Yomiuri]

Karakuri ningyo dolls are made of lightweight materials so they can move smoothly. The spiral springs were originally made of whale baleen and the gears were made of firm wood from Chinese quince trees. It can take three years to make a single doll, many of which end up on festival floats.

Hakata Dolls

Hakata, in northwest Kyushu, is famous for its traditional Japanese dolls, which are made with a kind of local clay that is ideal good for dollmaking. A center of dollmaking since the Edo Period, Hakata is the home of skilled craftsmen who hand produce exquisitely-detailed and realistic-looking miniature geisha girls, sumo wrestlers, Kabuki actors and samurai warriors.

The tradition of Hakata dollmaking reportedly began in the early 1600s when a tile maker working on a castle used some left over clay to make a doll that was so admired that he decided to devote himself to the art form and train some apprentices to continue the art. Dollmaking is such a big deal in Hakata today that on some holiday some residents ride around with dolls festooned to their cars.

Many of the dollmakers specialize in particularly kinds of dolls such as Kabuki actors or beautiful women in kimonos. And an effort is made to give each Hakata doll unique characteristics and an expressive face.

Hakata is also famous for its tops, which sometimes take more than five years to make, and top tricks. Some skilled performers and dancers can make a top spin in a cotton thread or the edge of a Japanese fan or even the cutting edge of a Japanese sword.

Hakata Dollmaking

The Hakata Dollmakers Association has about 100 members, each of whom uses the same centuries-old process of dollmaking. First, the clay is kneaded and sun dried in a plaster of Paris mold and then fired for 12 hours at 1800̊F in a kiln. The dolls are then painted by hand wit bright watercolors. The trickiest part, said one dollmaker, is making the eyebrows.

“Gofun”, the extremely stable white pigment used to paint dolls, is made from oyster shells that have been aged for at last 20 years and carefully sorted to extract the whitest white. The white powder is mixed with animal glue and plied to forms made of sawdust and glue. Hair is painted with “sumi” (see Calligraphy) and the red on the lips is made 50-year-old cochineal (see Canary Islands). Top-of-the-line dolls cost as much as $25,000.

A typical doll takes about four week s to make and cost anywhere from $64 and $2,400. Some traditional hand made dolls take six months or more to make and the armor alone on some samurai dolls can cost between $1000 and $50,000 dollars.

Hina Dolls

Girl's Day, is celebrated by families with girls who set up shelves in their homes with “hina” dolls a girl has received as presents arranged in a hierarchy. The dolls represent the ancient imperial court with the emperor and empress occupying the highest position on the shelf, three ladies in waiting on second shelf, and five court musicians on the third shelf. Ministers sit on either side of trays of food on the fourth step, and the fifth row features guards flanked by an orange tree and a cherry tree. Families also celebrate by drinking a special kind of sweetened sake, eating food symbolizing purity, praying for their girls' happiness.

The practice of displaying dolls like this began in the Edo Period and started as a way of warding off evil spirits. The festival has its origins a Chinese purification rite in which evil spirits are transferred to dolls that are cast adrift on a river. These days the hina dolls are very expensive and not meant to be caste away or played with. A girl traditionally receives the first dolls from her parents and grandparents at birth and on her first birthday. According to legend, if a mother does not pack away her dolls soon after the holiday her daughter will have trouble finding a husband.

Hina dolls are a way for parents to show their love and wish for their daughter’s health and happiness. The traditional is said to date back to the Heian Period (794-1192) and derived from two customs: 1) “ hina asobi “ (literally “playing with dolls”) and “ nagashi-bina “ (The practice of sending dolls down a rive or casting them out to sea to ger ride of evil spirits). Often times grandparents buy the dolls as a gift for their daughters.

Kokeshi Dolls

Kokeshi dolls are wooden figures decorated with vivid colors and delightful faces--are a form of folk art from the Tohoku region that, in addition to warming the heart, are said to possess healing power. Mangaka Tomoko Fuyukawa, a die-hard kokeshi collector, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, "Look at the simple use of colors and the adorable faces. I don't know why, but looking at them calms me.” Each doll in her collection has a unique face--some have large round eyes with bob hairstyles, while others have almond-shaped eyes with round noses. The pieces in her collections are priced from as low as 1,000 yen to more than 10,000 yen. [Source: Nao Yako, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 16, 2012]

Nao Yako wrote in The Yomiuri Shimbun: “Kokeshi dolls are believed to have made their debut in the Edo period (1603-1867) at Tohoku hot spring resorts. The toys were bought as souvenirs by visitors who came to partake in the therapeutic baths. To make them today, pieces of wood spun on a lathe are carved until they have a roundish shape. Skilled craftsmen then paint on the faces and body designs.

The different areas of Tohoku produce various types of dolls. For example, Naruko-style kokeshi from Miyagi Prefecture feature bangs at the top of the head tied with a string called a mizuhiki. Tsuchiyu-style dolls from Fukushima Prefecture have relatively small heads and slim bodies. Body designs also vary--from flowers to unique borders called "wheel lines." The designs are usually made with a limited number of colors, but each hue is vivid and distinctive. In all, there are 11 kokeshi styles in the six Tohoku prefectures.

Kokeshi were originally toys, and many are made with round heads and thin bodies to fit in a child's hand. Others are shaped like a basket. These "ejiko" dolls get their name from the basket newborn babies were placed in. "Kokeshi for a long time were simply an old, traditional craft, but they've recently become popular with young women," Fuyukawa said. She belongs to the kokeshi fan group Gombasha, which sells accessories for the dolls and holds kokeshi-themed events.

Two years ago, kokeshi book: Dento Kokeshi no Design (Traditional kokeshi design)--created by the design group cochae and published by Seigensha Art Publishing Inc.--scored a hit by depicting the dolls as pop art. Since, a series of kokeshi exhibitions aimed at young people have been held at fashion centers. "They've become stylish items for interior decorating. Find some you like and buy them," said Fuyukawa, who dedicates a shelf next to her bed to her kokeshi, which sits alongside flowers and postcards.

Some kokeshi are made so they can deliver letters to friends and family members.These dolls are actually tubular "envelopes" 11 centimeters tall that have lids. The body contains writing paper measuring 4.5 centimeters by 16.5 centimeters. These "letters" will actually be delivered by the post office. Just write the address on a strip of paper attached to the doll and attach a 120 yen stamp.

Dolls as Works of Art

In August 2012, the Grand Prince Hotel New Takanawa in Minato Ward, Tokyo hosted a doll exhibition, featuring about 700 pieces from both well-known Japanese artists and members of the public. In the exhibition, Doll Expo 2012, one of the attractions is works by six famous doll creators: Nobuko Akiyama, Yuki Atae, Sayume Okuda, Akimitsu Tomonaga, Komao Hayashi and Ryo Yoshida. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 10, 2012]

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The doll set "Imari Genso" (Imari fantasy) was made in 2006 by Hayashi, who is a living national treasure. The dolls express both classical beauty and nobility, and were made with a traditional technique from the Edo period (1603-1867) that uses a mixture of paulownia wood sawdust and wheat starch or other sticky materials.

Atae's "Peace" (2011) is a set of two cotton-fabric child dolls that the artist has given facial expressions imbued with innocence and simplicity. Atae, who was awarded the government's Medal with Yellow Ribbon, is known for his ability to depict everyday scenes and has become quite popular for his heartwarming style.

Doll Expo 2012 also showcases a selection of excellent creative dolls from talented amateur creators. About 200 pieces, chosen by five judges among 559 works submitted from around the country, are on display. The pieces vary from traditional Western dolls to modern robotlike figurines. Judge Masanori Aoyagi, director general of the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, said: "The contributors have incredible abilities for expression. They select the materials for their dolls carefully and adhere to high technical standards in production.”

Yamaki Nakamura, a 58-year-old housewife from Koshigaya, Saitama Prefecture, won the Grand Prix in the public section for her porcelain doll "Cocoa." The doll, which can sit or stand on its own, won judges over with the sensitivity of its beautiful but fragile facial expression. "I based the face on several different actresses and fashion models. It took two years to make the antetype. I figured, the more time and care I gave to making the doll, the greater my joy would be if I won the Grand Prix," Nakamura said.

Second prizes went to "Natural--Tsuki (moon)--" by 59-year-old doll-making teacher Miwako Ichijo of Yoshikawa, Saitama Prefecture, and "IOS" by Daisuke Shimodaira of Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, a 26-year-old company employee. "What kind of dolls fascinate you? People's tastes are influenced by psychology, values and aesthetics. I recommend looking for works that really catch your eye to heighten your appreciation of the dolls on display," Aoyagi said.

Japanese Swords

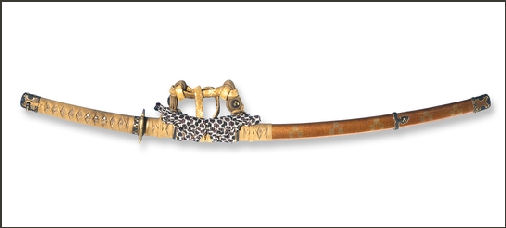

Swords have traditionally been the preferred weapon of samurai and officers. Swords themselves are symbols of power and honor. Often times swordsmiths were more famous than the people who used them.

Traditionally Japanese swords have had gently curved blades Long swords of this kind were first used by soldiers who fought on horseback in the Heian period (794-1192). What gives Japanese swords their strength and flexibility is the fact that the metal is folded over many times. When a sword is forged it is heated and then hammered flat, and after the metal is flat enough its is folded over. The same process is repeated many times until literally thousands of layers of metal are fussed together. [Source: William Graves, National Geographic, September 1972]

Swordmaking was banned and an estimated 5 million swords were destroyed after World War II. Many of the top quality blades were hidden; swordsmiths made quality kitchen knives to make ends meet. The ban on swords was lifted in 1953. Afterwards swordmaking was revived.

There are 2.3 million swords and more than 650 swordsmiths registered with the Japanese government. In recent years the films “The Last Samurai” and “Kill Bill” brought some attention to Japanese swords.

Japanese sword expert Paul Martin told the Daily Yomiuri, “Such a large number of Japanese swords would probably not have survived if they were regarded as nothing more than weapons. Through its long and complex history, the Japanese sword has come to be recognized by people throughout the world as an object with spiritual, artistic and economic values, in addition to its original function as a weapon.”

Books: “Japanese Swordsmiths” by Tamio Tsuchiko (Kodansha International); “The New Generation of Japanese Swordsmiths” by Tamio Tsuchiko (2002).

Websites: www.swordsofhonor.com and www.bushidojapaneseswords.com . Sokendo is a shop in Tokyo that specializes in samurai swords. It located at 28-1, 6-chrome, Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, tel. (03)-3499-8080, Web site www.sokendo.net

Shoso-In Sword

The Kingin Denso no Karatachi is an ancient sword made with elaborate techniques believed to have come from China's Tang dynasty (618-907) that is part of the Shoso-In collection in Nara. The actor Kotaro Satomi wrote in Yomiuri Shimbun, “This is a gorgeous sheath. I am just amazed that such a sheath has survived to this day. The blade, double-edged at its point, is beautiful, shining with a whitish silver color. The spirit of the swordsmith, who would have fired the metal repeatedly while creating the sword, must dwell in the blade. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 1, 2011]

Tokugawa Mitsukuni, feudal lord of the Mito clan and the hero of the "Mito Komon" TV drama, repeatedly says on the show, "A sword is not for slashing people but for governing one's own mind." Mitsukuni aimed to settle problems peacefully, without depending on arms. Emperor Shomu (701-756), who has been linked to the Karatachi sword, must have felt the same way.

When I'm acting, I sometimes use real swords. They photograph completely differently from fake swords, and I feel myself straightening up when I handle one.

sword blade

Parts and Types of Japanese Swords

The main parts of the sword are the blade, tsuba sword guard and the scarabat — all of which are made by specialized master craftsmen. Sword experts take a close look at the hamon or temper line of which there are many varieties, each with its respective “workings.” A closer looks at these workings reveals a multitude of patterns that create a masterpiece.

There are three major types of Japanese sword: 1) Kyoto-type from that latter part of the Heian periods from the 12th century to the Battle of Sekigahara at the end of the 16th century. 2) Shinto type, from the early Edo period in the early 17th century to the Tenmei era of the late 18th century; and 3) Shinshinto type, from the Bunka period of the early 19th century to the 1877 Haitourei decree banning the wearing of swords.

Japanese Swordmaking

Swordsmiths work with a fire that generates heat between 700 and 800 degrees C. They work in a darkened room so they can monitor the strength of the fire. The sword is covered in dirt when it is placed in the flames. Dipping a heated sword in water give it a natural curve. During the forging and hammering muddy water is used to protect the core of the sword. As a final touch the sword maker signs his named and makes his unique pattern on the blade of the sword.

The best quality steel is made from iron fillings melted in a forge that uses bellows to reach very high temperatures. Hard steel is pressed into soft metal before being reheated. Hammering removes impurities and shrinks the piece of steel to one tenth its original size.

Many sworsmiths work out of backyard workshops. Making a quality sword takes two or three weeks. Describing famous swordsmith Yoshido Yoshihara at work, Tom O’Neil wrote in National Geographic, “Yoshihara knelt on a straw mat and began to work with a narrow baton-size bar of steel. Working the bellows of the forge with one hand, he used the other to thrust the bar into a bed of blazing coals. As the bar turned yellow-hot, Yoshihara pulled it from the fire pit and with a metronome’s steady beat began hammering and thinning the heated metal, drawing out the curve and width of the blade.”

national treasure

Quality Swords in Japan

The best swords with specific names like Masamune were manufactured during the Kamakura period (1192-1333). Most swords deemed treasures date from this period, An antique sword made from the forge of the great fifteenth century maker, Kanemoto II, was shown in Japanese film slicing a machine-gun barrel in half. The sword was hammered and folded, and hammered and folded for months until the sword blade contained an estimated four million layers of finely forged steel. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

At “kanteikai” gatherings participants try to guess the period, province and school of swords by examining their structure, curvature, “hamon” (pattern of crystalline lines along the edge of the blade) and other features.

Okanehira is regarded as the greatest of all Japanese swords. With quality swords a close look at the hamon, or temper line, will reveal the intricate markings that create a masterpiece.

Japanese Knives and Planes

Sakai near Osaka is the primary production area for swords and knives. Blacksmiths and blade sharpeners have been active there for more than 600 years Some knife makers and swordsmiths outside of the town buy their goods in Sakai and put their names on them.

High-grade Japanese knives that sell between $100 and $300 a piece are becoming increasingly popular with chefs around the world. Their primary customers are chefs and chefs at Japanese restaurants but also other kinds of restaurants where precision cutting is essential. One knife maker told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “When viewed through a microscope. The blade of a Japanese-style cooking knife looks like a saw. They cut well.”

Master knife makers heat the metal in hearth and remove it when it reaches a certain temperature to hammer and shape it. They can gauge the temperature of the hearth just looking at the surface conditions of the metal.

Tokifusa Iizuka, from Sanjo City, is regarded as Japan's finest knifemaker. Selling for between $250 and $1,500, his knives are prized specialty by sushi chefs and made the same way as samurai swords with repeated pounding and folding. With handles made of wood and buffalo horn, they are so sharp they can slice an onion into nearly transparent, paper thin slices with cuts that are so clean that no tear-producing spray is produced.

Describing Iizuka at work, Valerie Reitman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, "Holding the red-hot metal with a pair of giant clippers, he folds it again and again, pounding it with a wooden mallet to create the blade's shape...Once the blade is cool, he begins the series of steps to grade and polish it, including attaching it to a rudimentary device, known as a “sen”, which looks like a clothespin turned on its side and manually shaving it with a razor attached to a cross-shaped device.”

"In the final stages, he puts the blade on sharpening stones and files away until they are smooth, occasionally dipping the knife in a gutter of green nitric acid that prevents rusting." Iizuka said he bought a $100,000 blade smoothing machine but discarded it because his skill was great than the machine.

Carpenter’s planes made by master blacksmith Sadahide Chiyozuru of Miki, Hyogo Prefecture, can sell for up to $5,000 a piece. Used mainly by shrine carpenters, they are capable of producing wood shavings that are as long and thin as toilet paper. The plane blades are made from iron and steel by hand through a repeated process of heating and tempering over a pine charcoal fire. To make the blade strong it is covered in mud, then places in a fire with a steadily rising temperature and then immersed in water. The shape is refined by repeatedly rubbing it on a stone. The blade of a finished plane is so sharp and strong it rarely needs sharpening.

Japanese Scissors Prized in the U.S

In January 2013, Jiji Press reported: “Cameron Diaz's hairdresser cuts the actress' hair with Japanese scissors. "Made in Japan" has a strong presence in the high-end scissors market for top U.S. hairstylists. Despite their expense, Japanese products are unmatched for the feel and quality of the cut they give, users say. It is not uncommon for a single pair to fetch 1,000 dollars. [Source: Jiji Press]

Shigeru Industrial Co., a major original equipment manufacturer of hairdressers' scissors, based in Tsubame, Niigata Prefecture, recently focused on its own high-end "b-mac" brand. In 2011, it established a sales unit in Illinois to promote the brand in the North American market. Hairdressing scissors for the U.S. market can be divided into luxury types, from Japan; intermediate ones from China and South Korea; and low-cost products from Pakistan, according to Sen Yamanaka, president of the U.S. unit.

B-mac scissors are made with a special material of high durability. Almost all of the production process is carried out in-house, with the finishing touches decided through the expert eyes and hands of craftsmen. In Beverly Hills, Calif., the masterfully created b-mac scissors have been endorsed by celebrity hairstylists whose clients include top actresses and other well-known personalities. Yamanaka said: "Rival Japanese companies also have great techniques. Japan's manufacturing capabilities cannot be imitated by other countries.”

Image Sources: National Museum in Tokyo, British Museum, Association for the Promotion of Traditional Crafts Industries in Japan, JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013