MOMOYAMA PERIOD PAINTERS

“The parallel cultivation of both originality and ancient tradition were strong themes in Momoyama period art,” Roderick Conway Morris wrote in the New York Times. “For example, while one screen depicts — against glittering backdrops of gold leaf — unmistakably Japanese scenes of ravens perched on snow-covered plum-tree branches on which the first small spring blossoms are flowering, another pair of screens in monochrome ink on paper shows sea- and mountain-scapes in the older Chinese style.” [Source: Roderick Conway Morris, New York Times, January 8, 2010]

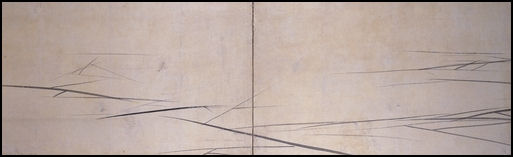

painting by Kano Eitokeo

“The former, expressions of the Momoyama sensibility at its most lyrical, have been attributed to Unkoku Togan (the founder of the Unkoku school), while the latter are by his son Unkoku Toeki. But, recent analysis of the techniques employed now suggests that Unkoku Toeki may well have been the author of both works.”

Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1603) is regarded as one of the greatest painters of the Momoyama Period, which itself is regarded as a period of great cultural flowering in Japan. Among his works are chilling landscapes, Buddhist paintings, portraits of famous and leading historical figures of his time. Describing his work “Pine Trees”, designated a national treasure, Robert Reed wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The almost photographic reality of this scene of pine trees surrounded in mist with one snowy mountain in the distance makes it hard to believe it is more that 400 years ago. “Quiet,” in all its natural, artistic and Buddhist implications, was one of Taokaku’s themes in this period of his career, and indeed, the profound quite achieved on those works justified its reputation as a pinnacle of Japanese ink painting.”

Kano School of Painting

Painting in the late sixteenth century was dominated by the Kano school, which enjoyed the backing of powerful sovereigns such as Oda Nobunaga. It was a polychrome style that aimed for maximum effect in the form of screen and wall painting. The most remarkable figure of the school was Kano Eitoku. The Kano school continued to expand its influence and managed to establish itself as the painting academy of the Tokugawa Shogunate. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The Kano School was famous for its gilded partition paintings of rich landscapes, flowers, birds and trees. It emerged in the Momoyama Period (1573-1603) and remained popular through the Edo Period. Originally based in Kyoto, it became official school of the shogunate and thus it method were kept secret. When some of its copybooks were leaked and published, the school scrambled to change its curriculum. It was founded and named after the artist Kano Masanobu (1434-1530). The Kano school was patronized by the authorities of the day and passed traditions down through a system of heredity or from master to apprentice.

The Kano school was led by members of the Kano family who inherited their positions. Artists were required to lean techniques by reproducing paintings drawn by it masters. The school originally stressed realism and strongly influenced by Chinese art bit over time become locked into a kind of formalism that stifled creativity and innovation. As part of their long training Kano school artist copied paintings regarded as masterpieces over and over again.

In the latter half of the 18th century the Kano school dominated Japan's art world with its decorative style of painting. The longevity of the Kano school has as much to do with politics and art. It endured well into the 19th century because it shifted from Kyoto to Tokyo when the Tokugawa shogunate established their capital there and remained loyal to them while recruiting new recruits from different clans.

Kano Tanyu (1602-74) is regarded as the greatest Kano school artist. He is celebrated as a great master who took the Kano school to new places. Working in the early 17th century at a time when the shogunate was moving from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo), he made wall paintings for Nagoya Castle and Nijo Castle in Kyoto and a series of scrolls depicting Tokugawa Ieyasu. He also convinced the school to move to Tokyo, a shrewd political move.

Among the other noteworthy Kano painters are Hanabusa Itcho (1652-17234), known for his ukiyo-e-influenced works and risque subjects; Kano Michinobu, who created light-hearted jovial works; and Kano Osanobu (1796-1846), who painted traditional subjects from interesting angles.

Rimpa School and Ogata Korin

The name Rimpa is associated with the style of Ogata Korin (1658-1716), who is acclaimed for his innovative design and large, gorgeous works. (Rim comes from "rin" in Korin, the artist, and "pa" means school.) Shinsaku Munakata, curator of an exhibit on Rimpa school art at the Idemitsu Museum in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri, Rimpa artists did not have rigid blood ties or discipline. "Although they admired past artists, they drew freely and adventurously. This is why there is such a great variety of Rimpa works," he said.

In contrast to the Kano school, which was patronized by the authorities of the day and passed traditions down through a system of heredity or from master to apprentice, the Rinpa school was a style of painting that developed through the inspiration and influence gained from other artists rather than the heredity system which was common at the time. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Rimpa School artists famous for their use of gold backgrounds include Honami Koetsu (1558-1637), Tawaraya Sotatsu (active in the late 16th-early 17th centuries), Korin and his younger brother Kenzan (1663-1743). Among the artists who preferred to use silver rather than gold were the Edo (Tokyo)-based artists Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828) and his student Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858), who revived Korin's style about a century he died but developed lighter, refined works.

Ogata Korin

“The best known figure in the Rinpa school was Ogata Korin, who was active in the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868). Once apprenticed to a Kano style master painter, Korin was influenced by the works of predecessors such as Tawaraya Sotatsu, who was known for bold composition and designs. Korin went on to develop a distinctive style that reflected the new sensibilities of the age. His style, known for its decorative aesthetics and refined design, had a huge influence over the art world, not just painting but also craft designs.

Ogata Korin (1658-1716) is acclaimed for his innovative design and large, gorgeous works. His folding screen, “General Tai Gong Wang”, has been designated an important property. “In this work,” Ihara wrote, “the legendary Chinese general, who was appointed to a high post by King Wen of the Zhou dynasty (ca 1,100-256 B.C.), is shown sitting near a river smiling humorously.” "The lines depicting the cliff in the background are aimed at attracting attention to his smile, which represents Oriental utopia," Munakata said. "The dark blue hem of his clothing illustrates Korin's good color sense."

Korin fully exercised his sense of design in the screen “Chinese Poet Bailetian Exchanging Poems with Shinto God of Sumiyoshi “ . The repetition of undulating waves across this piece and a tilted boat carrying the poet create a tense but appealing atmosphere. About a century later, Hoitsu superbly transformed Korin's theme and style into a pair of folding screens, “Wind and Thunder Gods “.

Two popular pieces by eminent painter Ogata Korin (1658-1716), “Irises “ and “Eight Bridges “ are owned respectively by the Nezu Museum in Minato Ward, Tokyo and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Irises and Eight Bridges feature the same flower drawn in vivid colors on a gold leaf background. The pieces are themed on The Tales of Ise, a well-known Japanese collection of waka poems and narratives created in the Heian Period (794-1192). A prized Korin work at The Tokyo National Museum is “Waves at Matsushima “.

Sulfur Used in Popular Ogata Korin Painting

In December 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Scientists have discovered that the enchanting water pattern in the popular "Red and White Plum Blossoms" painting from the Edo period (1603-1867) was created by sulfurating silver foil into a black background. The mid-Edo period piece, designated a national treasure and drawn on a pair of scrolls, is a masterpiece of Ogata Korin (1658-1716), one of the most prominent painters in Japanese art history. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 23, 2011]

Ogata's technique in this piece is a popular theme in studies by art experts, particularly the undulating silver wave pattern drawn on the black river in the center of the painting. A team of researchers led by Prof. Izumi Nakai of Tokyo University of Science examined the drawing in October using methods such as X-ray diffraction, a technique used to analyze crystal structures of materials. The team detected silver leaves and sulfur among other substances in the water pattern.

According to the team's findings, researchers hypothesized that silver leaves were first pasted to create the river before a nonsulfurated, unidentified substance was used to draw the water pattern. Powdered sulfur was then spread on the silver leaves to change the river's background color to black.

Bamboo and Plums by Ogata Korin

Maruyama Okyo

Meanwhile, European painting influenced a growing number of Japanese painters late in the Edo period. Major artists such as Maruyama Okyo, Matsumura Goshun, and Ito Jakuchu combined aspects of Japanese, Chinese, and Western styles.

The artist Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) and his student Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) were known for their bold, innovative style. Robert Reed wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “In the latter half of the 18th century, when the Kano school dominated Japan's art world with its decorative style of painting, the painter Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) emerged in Kyoto to establish a school of his own that offered a fresh alternative. His new style of painting was based on a practice that was quite uncommon at the time: sketching directly from nature.” [Source: Robert Reed, Daily Yomiuri, October 29, 2010]

“While those who favored the Kano style criticized Okyo's dependence on from-life studies as a weakness, the popularity of his style with its straightforward realism spread steadily. The first to embrace it were the townspeople and merchant class of Kyoto, but eventually it found admirers in the highest strata of society. One of Okyo's major patrons was the wealthy Kyoto-based Mitsui family, which would later create a business empire in modern Japan as the Mitsui zaibatsu.

“It was perspective experiments...as well as a knowledge and love of Chinese painting and mastery of the Western techniques of using highlights and shadow to create the illusion of three-dimensional form — which Okyo learned from European etchings — that eventually enabled the artist to develop a style of his own to rival that of the Kano school,” Redd wrote. “Apprentices soon began flocking to the "Maruyama school" and commissions for works came in, initially from the townspeople, but eventually from the Shogunate and even the Imperial family.”

Okyo was known for his sliding door paintings and is regarded as the father of modern Japanese painting and one of the first Japanese artist to develop truly unique Japanese style. He did this in part by blending sophisticated technique, elegance and realism, and merging Chinese traditions with Western methods such as perspective, and drawing directly from nature and models rather than from impressions of it. In 2007, Okyo’s “Cranes” was sold for $1,050,000 — triple the asking price — at a Christie’s auction. The 18th century pair of screens was the first Japanese work to sell for more an $1 million in over a decade.

Maruyama Okyo cracked ice cool view for summer

Maruyama Okyo’s Paintings

Among Okyo masterpieces are “Unyru-zu” (“Dragon and Clouds”) and “Botan Kujaku-zu” (“Peonies and Peacocks”). The most famous works by Rosetsu are “Tora-zu” (“Tiger”) and “Yamauba-za” (“Mountain Woman”). Both artists produced large painting that over powered the viewer. The relationship between Okyo and Rosetu was stormy. Okyo kicked Rosetu out of his school three times but admired his technique enough to give him some important commissions. Rosetu died under mysterious circumstances when he was 46. It has been suggested that one of his rivals poisoned him out of jealousy.

Some of the greatest masterpieces of Okyo's mature style have seldom been seen by the public, however, because they were painted on the fusuma sliding doors and wall panels of temples in Kyoto and Hyogo prefecture during Okyo's later years.” These include the national treasure “Pine Trees in Snow “ (1786) and the glorious “Peacocks and Pine Trees” (1795) covering 16 sliding door panels from the Daijoji Temple in Hyogo — also known as "Okyo Temple." [Source: Robert Reed, Daily Yomiuri, October 29, 2010]

Among his magnificent fusuma paintings are “Plum Tree in the Snow “ (1789) from Sodoji Temple and “Old Plum Tree “ (1784) from the Tokyo National Museum collection. “In these works,” Reed wrote, “perhaps better than any others, we see why Okyo's mastery of spatial illusion — or “depth” — earned him the title “painter of space.” Standing before these works, you feel that the branches of the plum trees thrust out into the room from between the frames of the sliding door panels. It is an experience no printed reproduction in a book can even begin to suggest. Neither is there any substitute for actually standing in front of Pine Trees in Snow and feeling the chill and the silence in the air.

Maruyama Okyo’s 3-D Paintings

"Like any aspiring artist of the day, Okyo had to study under a Kano school teacher in order to master the art of using the brush and ink," explains the show's curator, Kazutaka Higuchi, a curator at the Mitsui Memorial Museum, told the Daily Yomiuri. "But, Okyo's first success with painting came in the specialized genre of paintings for the stereoscope viewers called nozoki-megane that were popular at the time. These were optical devices that created a 3-D effect when a painting executed with linear perspective is viewed through them." [Source: Robert Reed, Daily Yomiuri, October 29, 2010]

It is believed that Okyo first began painting these pictures — called megane-e in Japanese — while working at a toy store while still in his teens. "The stereoscope devices originated in Europe and were imported to Japan mainly from China, so the scenes in the paintings that came with them were either European or Chinese. Soon, however, the Japanese wanted more familiar scenes for their stereoscopes and the young Okyo was one of the first to master the Western style single-vanishing-point perspective and paint scenes of Kyoto for the stereoscope," Higuchi explains.

Examples of stereoscope paintings including renderings of such familiar Kyoto sites as Kiyomizu Temple and Shijo Bridge, as well as famed landscapes such as Yoshino with the cherry tree in bloom and Yodogawa river scenes. Because the paintings are unsigned and done in a standardized style, there is no proof the young Okyo actually painted them, but experts strongly believe he did.

“Although these same scenes were often the subjects of Kano school painters, the aim of a stereoscope painting was to create the illusion that the viewer was actually looking at the scene with their own eyes, rather than through the eyes of a painter using a stylized visual vocabulary,” Reed wrote. Works that followed, like the scroll painting titled Banks of the Yodo River (1765) in which Okyo employed a new type of perspective clearly aimed at creating that feeling of "looking at the scene with one's own eyes."The result is a unique wedding of Western-style linear perspective and the traditional Japanese bird's-eye perspective.

Hon'ami Koetsu

Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637) is sometimes called the Leonardo da Vinci of Japanese art because of his extraordinary talent in a number of different art forms: painting, calligraphy, ceramics, poetry, the tea ceremony and lacquerware. He was equally adept at producing minimalist tea ceremony bowls, expressive paintings and wonderfully designed lacquer boxes.

Born into a family of swordsmiths, Koetsu prospered under the rule of the shogun Tokuagawa Ieyasu, who gave the artist a small village near Kyoto to work in. He worked with many other artists of his time and was described by some as good an "art director" as an "artist." Through his artistic career he also engaged in his trade, sword polishing.

Edo Period Artists

Humorous and innovative Edo artists also included Sengai Gibon, the creator of an amusing and beautiful rendering of a smiling frog in meditation; and Kuniyoshi who produced images of tattooed warriors fighting giant spiders and humongous snakes.

Ito Jakuchi (1716-1800) is known for his irreverent religious imagery, his use of vegetables as Buddhist symbols, and his experimentation with mosaic-like pointillism and other styles. He painted images of cranes,, eagles, plum blossoms, elephants, tigers and reeds waving in the snow. In “Grapevies” he paints leaves without outlines, using only wet washes in the so-called “boneless manner.” The tightly twisting tendrils and interwoven vines have not been allowed to cross.

Kawanabe Kyosai was another painter known for his humorous works. Describing a painting by Kyosai of the monk Daruma, Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Glowering on the wall is the ferocious monk...the legendary founder of the discipline of Zen. His eyes bulge. His brow is furrowed, his chest hairy. He is furious. Similarly intense are the coarse, impatient brush stroke of the gold-embroidered robes. Daruma dares the viewer to conquer self deception . But it is hard to take him seriously. Painting of this sort were once religious objects. This one is a party piece.”

Other well-regarded artists include Katayama Yokoku, who produced Chinese-style hanging scrolls: Watanabe Shiko (1883-1755), famous for his images of cranes; Nagasawa Rosetu, famed for his ghostly images of women; Mori Sosen (1747-1821), who painted such wonderful images of monkey people and said he would be reincarnted as a monk; and Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828), the creator of elegant and refined screens and scrolls chronicling the changing seasons such as “Flowers and Grasses of Summer and Autumn”.

The brothers Ogata Korin and Ogata Kenzan produced lovely works. Ogata Korin (1658-1716) was a master of design and producer of lyrical paintings like “The Eight-Fold Bridge”). Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743) was a skilled potter who made ceramics with picturelike inscriptions. Hoitsu, Ogata Korin and Kiitsu all did their own versions “Wind and Thunder Gods”.

Image Sources: National Museum of Tokyo

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013