ELDERLY IN JAPAN

Japan has the highest proportion of elderly and the lowest proportion of young people in the world, with people 65 and over making up 21.5 percent of the population in 2007 and people 15 and under making up 13.6 percent of the population. In contrast the proportion of people over 65 was 5.7 percent in 1960 and the proportion of people under 15 was 30.2 percent. In Japan there is even a holiday for the elderly: Respect for the Aged Day.

At 86.39 years for women and 79.64 years for men (as of 2010), Japan has the longest life expectancies in the world. Women make up just under 60 percent of the population aged 65 and up and more than 70 percent of the population aged 85 and up. To help care for the growing population of elderly, a long-term care insurance system was implemented in 2000. When care for elderly relatives is provided in the home, the major burden is generally borne by a woman, whether she works or not. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

By 2015, one in four Japanese will be over 65. In 2003, there were 24.3 million elderly people over 65. Of these 14.3 million were between 65 and 74 and 10 million were over 75. In 2000, the number of people over 65 outnumbered people under 15 for the first time. By the year 2025, 29 percent of the population will be over 65 and 35.7 percent in 2050.

In September 2008, the number of people 70 and over reached 20 million for the first time. The number of people exceeding the age of 80 reached 8 million in 2010. By 2050, 15 percent the population is expected to be over 80.

The Showa generation that was born before World War II are regarded as the people that made Japan what it is. Brought up on Confucian values they endured the war but did not directly participate in it, struggled with food shortages and hard times after the war and worked hard and lived frugally, and set the economic miracle of he 1950s, 60 and 70s in motion.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Japan and the Elderly everything2.com ; About.com on Okinawan Longevity longevity.about.com ; Okinawan Centenary Study okicent.org ; Links in this Website: PENSIONS, NEGLECT AND PROBLEMS FOR ELDERLY JAPANESE Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Care of Elderly Care of Elderly in Japan and Sweden wao.or.jp/yamanoi ; Elderly Care Research hope.edu/pr ; Caring for Japan’s Elderly iias.nl/nl ; Japanese Robots Held the Elderly USA Today ; Social Secuirty Social Security in Japan mofa.go.jp/j_info ; Reforming Social Security in Japan ier.hit-u.ac.jp/pie ; Wikipedia article on Social Welfare in Japan Wikipedia ; Statistical Handbook of Japan stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare mhlw.go.jp/english ; National Institute of Population and Social Security Research ipss.go.jp

Population and Demographics: Wikipedia article on Japanese Demographics Wikipedia ; Dilemma Posed by Japan’s Population Decline japanesestudies.org.uk Statistical Handbook of Japan (Japanese Government Population Statistics) stat.go.jp/english/data and stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/ nenkan ; News stat.go.jp ; Population Projections ipss.go.jp ; National Institute of Population and Social Security Research ipss.go.jp ; What Japan Thinks, a blog with info on demographics and statistics whatjapanthinks.com ; Human Mortality Database mortality.org

Long Live Japanese

In 2006, Japan remained No.1 in life expectancy, tied with Monaco and San Marino at 82 years according to the World Health Organization. By gender, Japanese females placed at the top at 86 years while males in Japan, Iceland and San Marino tied for first at 79 years.

Japanese women have topped the list of the world's longest living people for more than a dozen consecutive years. By 2050, the average lifespan of Japanese women is expected to exceed 90 and women over 65 will make up 25 percent of the population.

Long-Live Okinawans

Okinawa is the home of the longest-living people in the world and the highest percentage of centenarians in Japan are in Okinawa. There are 47 centenarians per 100,000 people, the highest rate in the world (by comparison there only 10 per 100,000 in the United States). The average life expectancy of Okinawans is 82 years (86 for women and 78 for men), compared to 79.9 for all Japanese. The ancient Chinese called Okinawa the "Land of the Immortals." [Source: Craig Willcox, the Okinawa Centenarian Study]

The concentrations of people over 100 on Okinawa is five times higher than the rest of Japan. As of 2005, there were more than 700 people in Okinawa who were 100 year or older — about 86 percent of them women. The oldest man on both Japan and Okinawa, 108-year-old Genkan Tonaki, only recently gave up proposing to nurses. He worked in sugar cane fields until he retired at the age of 85 and used to drink six bottles of beer a day.

Heart disease, strokes, dementia, clogged arteries, and high cholesterol are rare. Cancer rates, are low. Okinawans suffer 80 percent fewer heart attacks than North Americans, and are twice as likely to survive if they have one. They have a forth of the breast cancer and prostate cancer rates and a third less dementia than Americans. There has traditionally been little obesity in Okinawa and old people have stronger-the-expected bones.

One Okinawan proverb goes: “At 70 you are but a children at 80 you are merely a youth, and at 90 if the ancestor invite you into heaven, ask them to wait until you are 100, and then you might consider it”.

Reasons for Long-Live Okinawans

The extraordinary longevity of Okinawans has been attributed to an active social life, low stress levels, a strong sense of community, lots of exercise, respect for older people, “moai” (traditional support networks), remaining involved, having a strong sense of purpose, working into the 80s or 90s, and having a lust for life summed up by the expression “that which makes one’s life worth living.” Some individual Okinawans credit their longevity to drinking a mixture of garlic, honey, turmeric, aloe and “awamori” liquor before they go to bed.

The traditional Okinawan protein- and mineral-rich, plant-based diet is also regarded as important factor in extending the life span of Okinawans. The traditional Okinawan diet is very low in calories, low in salt, but high in nutrition, flavinoids and anti-oxidants. Okinawans eat a wide variety of plants, especially green-yellow vegetables and soy products. Okinawans consume 60 to 120 grams of soy products a day, more than any other people on Earth.

Okinawans practice “hara hara bu” (only eating until they are 80 percent full). The average intake of calories for elderly Okinawans is only 1800 per day compared to 2,500 a day for the average Western male. Their body mass index (BMI) ranges between 18 and 22, with 23 and below regarded as lean.

Okinawan foods which are said to contribute to a long life are sweet potatoes, which used to be a staple of the Okinawan diet; “nabera”, a cucumber-like gourd; snake gourds, “mozuka” (seaweed); “uuchin”; a kind of ginger; “umjanbaa,” a leafy vegetable rich in vitamins and minerals; tumeric, Chinese radishes, Okinawan shallots and mugwort. “Goya”, a bitter-flavored Okinawan vegetable resembling a zucchini with warts, is particularly valued as a health food. It has twice the vitamin C of lemons and is said to contain anti-aging agents for the skin.

With all this said, the health of Okinawans is declining. Okinawans are now the fattest people in Japan and men 55 and younger have the highest relative mortality rate in the country. The decline has been attributed to lifestyle and dietary changes.

Genetics seems to have relatively little bearing on health. When Okinawans grow up in other countries there disease and health problems are more reflective of their adopted country than their homeland. As Okinawans have adopted a more American-style diet, their rates of cancer and heart disease have climbed.

Book: “The Okinawan Program” (2001),a New York Times bestseller, and “The Okinawan Diet Plan: Get Leaner, Live Longer and Never Feel Hungry” (2004) by D. Craig Wilcox, Bradley Wilcox and Makato Suzuki.

Retirees in Japan

The retirement age in 1995 was 66.5 compared to 67.2 in 1960. About 350,000 people retired a year in the 1990s. There was a sudden surge of retirees in 2007 to 500,000 a year as some of the seven million Japanese baby boomers, defined as those born between 1947 and 1949, began retiring.

One study found that elderly women who lived with their retired husbands were twice as likely to die than women who lived on their own.

Divorce rates are high among retirees. According to one marketing firm many men over 50 want to die before their wives and many wives want them to die because they view widowhood as the best time of their life. This sentiment is based at least partly on the fact that a woman’s life is bound by duty and that widowhood is the only time she is free.

Expressions for retired men include "oversize trash" (a useless retired husband equated with unwanted items that cost more to haul to the dump), "wet leaves" (a useless retired husband compared to sticky leaves that can't be sept away from the house).

Survey indicate that many Japanese believe that raising the retirement age is the best way for the government to finance services of its aging population.

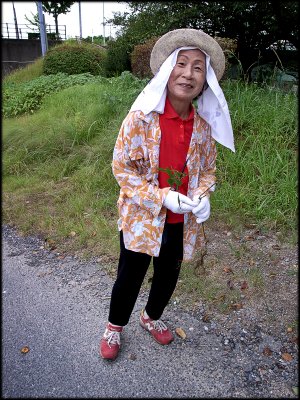

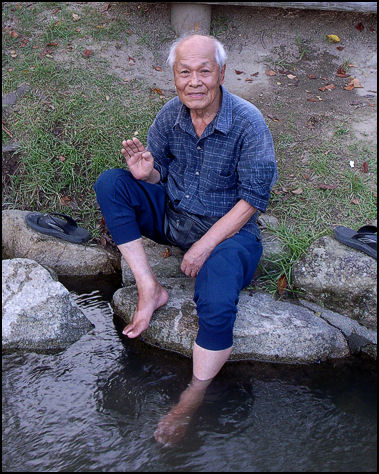

Seniors, Sports and Physical Activity in Japan

According to Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Japanese are vigorously enjoying leisure activities in their retirement years. Retirees who are particularly health-conscious are using their free time to play tennis or golf, go jogging, or have fun hiking and mountaineering. There is also a strong interest in studying and taking lessons among retirees, who are engaging in lifelong learning on topics that interest them by actively participating in classes and seminars held at local cultural centers or universities. Many retirees are also traveling to a wide array of destinations for a variety of reasons, whether visiting scenic and historical spots of interest to them or hot-spring resorts to improve their health. There are also many who are traveling overseas, which has increased the proportion of elderly among overseas travelers. The elderly have also become more eager to play an active social role through local volunteer activities and the like. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

An official at the Japanese Health Ministry told the Washington Post, “Japanese seniors are not only living longer but their health in generally excellent, and as a group they appear to be getting healthier. They are doing more and more exercise while younger and are spending more time sitting and scanning the Internet.” There is a lot of talk of the toughness of the older generation. Having spent a childhood amid postwar deprivation, they see themselves as resilient, self-sufficient, not soft like today's youth with their electronic gadgets. A study in the early 2000s, found that 49.6 percent of seniors exercise regularly, 63.6 percent don’t over eat and 64.2 percent sleep well. In rural areas, seniors still do heavy agricultural chores. In the cities many get around without cars. Many of these people endured hard times during and after World War II and remained tough even when the rest of Japan grew soft with prosperity.

According to a 2001 government white paper, three forth of Japanese over 65 said they have no physical problems that affect their daily life and 50 percent of those over 60 go out daily and 90 percent of them drive two or three times a week. The same report said that half of the elderly participated in some kind of social activity and 70 percent were interested in taking part in a volunteer activity.

Gateball (a kind of croquet), swimming pool walking and tai-chi-like morning exercises are popular among retirees. Soft tennis, a form of tennis played with a soft ball and a different scoring system, is also popular with elderly people.

In April 2010, 73-year-old Noriko Iida of Niiza, Saitama became the oldest Japanese — male or female — to finish the 250-kilometer Marathon de Sables in the Sahara. Iida finished in 70 hours and 5 minutes and 38 seconds, which was good enough for 894th place out of the 923 who completed the race. Her goal now is to become the oldest woman to complete the race (that record is held by a French woman who did it when she 75).

In March 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A 97-year-old man was arrested on suspicion of trying to kill a female relative by slashing her with a sword after he walked about 100 meters to her home using his walker, police said. ccording to the police, Yoshio Kawamura cut the 84-year-old woman's left hand at about 9 a.m. while saying, "I'll kill you." The sword had a 50-centimeter blade. [Source: April 4, 2012]

Gateball and Ground Golf

Gateball is played with three wickets and a single post. Modeled after croquet, with elements of golf and curling thrown in, it is a team game with five members on two teams hitting balls in turn, and requires great skill to place the ball where the team captain wants. One missed shot can spell doom for a team. When players hit their opponent's ball many do it gently rather than aggressively.

Gateball was created in Memurocho, Hokkaido in 1947. The game was originally devised as an easy game for children but it was picked up by a home for the elderly in Kumamoto Prefecture as good game for old people after the Tokyo Olympics generated nationwide interest in sports. After that gateball quickly caught on with elderly across Japan. According to the Japan Gateball Union, more than 6 million people played the sport when it was at its peak in 1990. Now about 2 million play it.

In the late 2000s gateball became increasingly popular with young people with some high schools having teams and competing in the All Japan Junior Gateball Games. One team player told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “It’s so thrilling when my turn to hit comes around. Even if someone misses a shot, our teamwork can guide us to victory.” In the meantime many elderly people have switched to ground golf — a game in which players hit balls with a mallet into cages set up around a field.

Senior Mountain Climbers and Adventurers in Japan

elderly climbers on Mt. Fuji In May 2003, 70-year-old Yuichiro Miura, a high school headmaster from Sapporo, became the oldest man to reach the summit of Mt. Everest. He broke the record set in 2001 by another Japanese man, 65-year-old Tomiyasu Ishikawa. Miura also holds the record for being he oldest man to ski down the highest peaks of each of the world’s seven continents. Miura was the central figure in the Oscar-winning documentary “The Man Who skied Down Everest”.

In May 2007, 71-year-old retired teacher Katsusuke Yanagisawa became the oldest person to reach the summit of Mt. Everest. On reaching the summit he said, “I was pretty much at ease mentally at the summit, like I could sing a song.”

In May 2008, Miura became the oldest Japanese to ascend Everest at the age of 75. He failed in his bid to be the oldest man to scale Everest when Min Mahadur Sherchan, a 76-year-old Nepalese, made it to the top the previous day. Miura climbed to the summit from the Nepalese side. Restrictions in Tibet following th Olympic torch relay protests in April 2008 prevented him from ascending Everest from the Tibetan side as he had planned.

In 2003, Keizo Miura skied down Mount Blanc in France at the age of 99. In October 1994, 100-year-old Ichijirou Araya climbed Mt. Fuji. In 2008, 71-year-old Tomiyasu Ishikawa climbed the highest mountain in Antarctica and thus finished his achievement of climbing the highest peaks in all seven continents.

In 2004, 11 Japanese retirees, with an average age of 63, trekked across the forbidding Taklimakan Desert in China. They covered 750 miles in 73 days and endured temperatures of -15̊F. A popular commercial shows a 68-year-old wrinkled farmer doing giant swings on the horizontal bar.

Skiing, mountaineering and snowshoeing trips have become popular with elder and middle-aged sportsmen. Particularly dangerous are trips which involving climbing up a mountain and skiing down, with avalanches and falls being the primary dangers. In May 2005, three people were killed when an avalanche smothered a group of five people in the Nagano area

See Recreation, Hiking

Dating and Young Princes in Japan

An increasing number of widowed, single and divorced elderly people are dating and turning to websites like match.com to find partners.

In the mid 2000s it became a big thing for middle-aged and elderly women to swoon over teenage “princes” such as the 16-year-old kabuki actor Taichi Saotome, the 18-year-old golfer Ryo Ishikawa, and the 15-year-old kickboxer Hiroya. The trend arguable began with the infatuation with Korean television star Bae Yong Joon.

Noriko Mizuta, a professor of women studies at Josai International University told the Daily Yomiuri, “I thinks these teenagers are icons to these women, and arouse their maternal instincts..,and many women are deeply disillusioned with their husbands, who are suppose dot be their partners for life. When they were busy raising children, they couldn’t afford to have fun for themselves. But now, they feel like they want to enjoy their lives.”

Retirement and Work in Japan

Many elderly people work. In 2005, 22.2 percent of Japanese aged 65 or older were employed, compared to 14.4 percent in the United States and 2.9 percent in Germany in 2004. Many work because they want to. One 60-year-old man told Reuters he had no intention of retiring soon. “I’m still healthy and I can work. Besides, I wouldn’t now what to do with myself if I stayed at home all day.”

The government is trying to encourage people to work longer. According to a 2001 government white paper, elderly make up 7.3 percent of the labor force. The average income for working and non-working men was $25,000, and $8,000 for elderly women.

Many of the working elderly work at menial jobs such as flag men, playground sweepers and park cleaners. A typical retiree receives $2,000 a month in pension and $700 a month from part time work.

The government is encouraging older people to work longer as a way to avoid paying pension benefits and stave off a labor shortage. Recently legislation was passed that required companies to push back the official retirement age to 65 or abolish the retirement age altogether, or give retirees an option to work part time. The legislation is easily ignored because there are no punishments for breaking the rules.

There is also an efforts to retirees to take up farming and many retirees are taking advantage of programs intended to get younger people to become farmers.

Nearly 50 Percent of Firms Let Elderly People Work Beyond Age 65

in October 2012, Jiji Press reported: “The proportion of Japanese companies where employees can work until the age of 65 or over rose 0.9 percentage point from the previous year to a record 48.8 percent in 2012, the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry said in a report.The report, released Thursday, is based on data as of June 1 from about 140,000 companies with workforces of 31 or more. The figure is the highest since the survey began in 2006, thanks to moves by short-staffed small businesses to make use of older workers, the report said. [Source: Jiji Press, October 20, 2012]

However, only 24.3 percent of companies with 301 or more employees allow employment of workers aged 65 or older, up 0.5 point from the previous year, according to the report. Such large companies will have to take necessary steps promptly, as revised legislation was enacted earlier this year to oblige companies to allow employees to continue working up to 65 years of age.

The law was revised in view of planned changes to the public pension system. The age of eligibility for pensions will be gradually raised from 60 to 65, beginning in April 2013. Currently, the ministry requires businesses to introduce at least one measure to secure employment for anyone up to age 65. Such measures include raising or abolishing the retirement age, and reemploying people past the retirement age. But the current reemployment system allows companies to choose eligible workers based on labor-management negotiations.

Housing Opportunities for the Elderly

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Only a small number of facilities are available for elderly people who wish to live independently from their families. "The number of nursing homes has increased but the nation lags in providing programs to help assist the healthy elderly living alone," said Katsuhiko Fujimori, chief researcher at the Mizuho Information and Research Institute. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 3, 2012]

“According to estimates by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the number of people aged 65 or older will account for about one-third of Japan's total population in 2030. Of these, more than 20 percent are expected to be living alone. However, barrier-free housing for senior citizens can accommodate just 1.5 percent of the elderly as of 2008. The percentage is one-fifth of that in Denmark and Britain. The government hopes to raise the proportion to 3 percent to 5 percent by 2020. It launched a project in October last year to promote construction of housing for the elderly featuring various services, including confirmation of their safety.

“The Cabinet Office's survey of the elderly conducted in fiscal 2005 showed 24 percent of elderly males living alone did not associate with neighbors and 17 percent had no one to consult with on problems. There is a paper-thin line between the elderly living independently and living in isolation. "Providing facilities alone cannot create human bonds," said Tetsuo Tsuji, a professor at the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Tokyo.

Laws and the Elderly in Japan

Beginning in 2008, drivers over 75 were required to put a symbol on their car that showed others that an elderly driver was behind the wheel. In some areas elderly drivers over 65 are being given coupons at hotels and department stores and discounts on public transportation to encourage them to give up their driving license. The government is trying to get elderly driver off the road. In 2007, drivers over 65 accounted for 47.5 percent of traffic accident deaths and were recognized as the cause of 102,961 traffic accidents, 3,108 more than in the previous year and twice as many as in 1997.

In January 2010, the Hatoyama government would raise the retirement age from 60 to 65 for some pension plans. Under the plan workers would contribute more to the system and get back more when they retire

Products for the Elderly in Japan

People over 65 control half the wealth in Japan. Many of them have loads of savings and generous pension packages and the kind of disposable income what makes companies drool. In recent years companies are aiming more and products at them.

Toymakers are starting to turn their attention away from children to some extent to devote more attention seniors. Some companies for example, have developed robot dogs and seals aimed at old people living alone. Other industries such as processed food, electronics and construction are also orienting products towards seniors.

Products for senior include lightweight, easy-to-handle luggage; easy-to-grip pens, scissors and staplers; hand cushions for holding shopping bags; easy-to-use cell phones with a minimum of buttons; low-calorie, lightly-season foods; and vitamin supplements designed for the aged.

New technology is being developed all the time to assist elderly people. Among these are beds outfit with sensors that automatically lock doors; toilet seats raise automatically when someone enters the bathroom room; showers that have places for people to sit; and a robot bear that can speak 2,000 phrases and can relay messages from a computer.

Toyota has developed dashboards with large easy-to-read numbers and letters, hand controls for the brake and accelerator and seats that swivel sideways making it easier to get in and out. Sales for cars with these features has been exceptionally good.

Electric wheelchairs with steering wheels are very popular with the elderly. They cost around $2,000 and are driven on the sidewalk and n roads and used for shopping and to run errands.

A Tokyo-based company called Prope produces an airbag for the elderly that sells foe about $1,500, weighs 1.1 kilograms and fits into a travelers waist bag. It can inflate in one tenth of a second and protect the wearer in the case of a fall.

To attract elderly customers more companies are making accommodation for them. For example, the Aeon supermarket chain has made aisles wider and introduced elderly-friendly cars for seniors.

Robots for the Elderly in Japan

Robots are increasingly being looked upon as a means of dealing with Japan’s aging population. Robots have been developed that help people who have trouble walking and feeding or taking care of themselves.

Robot pets have shown to be beneficial to elderly people who need companionship. Paro is a white furry, seal-shaped robot designed by Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture. Selected by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s most soothing robot, it is used to cheer up depressed patients in hospitals and nursing homes. It is covered in soft artificial fur and behave like a cuddly animal when held and responds to people’s actions and words, moving its head and flippers and making baby seal noises depending on what people do.

Paro is 57 centimeters long and weighs 2.7 kilograms. Selling for around $3,500, it has received high marks from facilities for children and the elderly in 20 countries. People have been observed singing lullabies to Paro and showering it with the same kind of attention given to children or living pets. Paro is used in Denmark in therapy sessions at welfare facilities for the aged. The Danish film maker Phie Ambo made a documentary about the relation between humans and robots, using video of people in Europe and Japan interacting with Paro.

Robot dogs have been shown to improve the moods of elderly patients with severe dementia. The robots are designed to be companions and aides, reminding their owners to take their medicine and other things. Studies have shown that patients with soft, furry exteriors are desired. Aibo and other robot dogs have been outfitted with soft coats to make them desirable.

Paro Robot Therapy for the Elderly

"You're gentle and smart. You're a good pet, aren't you?" Tomoe Wakabayashi, 92, says as she affectionately caresses her companion Paro. Paro, a seal-shaped robot, replies with a loving "Kyuuu" while wagging its tail. Wakabayashi is a resident at Lumiere, a group home for people who suffer from dementia in Kanagawa Ward, Yokohama. She began suffering from gaps in her memory due to dementia about five years ago. She became a resident at the facility in October 2011 after she began suffering from other dementia symptoms, including violent outbursts at her family.When she first started living at the facility, she always sat alone in her room and didn't speak to other residents. At dinnertime, she insisted the facility let her go home. However, since spending time with Paro, she has vastly improved. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 14, 2012]

Using robots such as Paro, a method known as "robot therapy," has been reported to help soothe and ease depression among dementia patients. As a result, its use has become more popular in Japan and overseas. Whenever facility employees ask her to take care of Paro, Wakabayashi begins chatting away with the robot. She smiles more often and sometimes sleeps with Paro in her arms at night.

"I'm surprised that Paro has had a better therapeutic effect than we expected," said Misako Kawasaki, the facility's manager. According to Kawasaki, Wakabayashi seems to remember raising her children and grandchildren. "Being with Paro probably reminds her of happy times. It seems the experience brings more energy to her life, too," Kawasaki said. Paro has also helped cheer up and reduce stress for 17 other residents at the facility.

The robot seal was developed by the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, and was first sold commercially in 2005. Paro's unique features lie in its movements. The robot has visual, touch and audio sensors built into its body, and its programming allows it to recognize stimuli by moving seven body parts in a charming manner. Many academic theses have been written acknowledging its beneficial therapeutic effects. So far, more than 2,200 units have been manufactured for sale in Japan and overseas.

After being put on sale, Paro was soon primarily used to help care for elderly dementia patients in the United States and Europe, where the effects of animal therapy have already been recognized Using real animals in therapy is difficult at medical and welfare facilities as they may potentially carry contagious diseases or bite patients. Paro, however, carries no such risk. In the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration certified Paro as a type of medical equipment. In Denmark, many local governments have introduced the robot to care for dementia patients at nursing homes.

Meanwhile, in Japan, the robot was initially bought by individuals as a pet. However, it has been reported that an increasing number of medical and welfare facilities are buying the robot after hearing it was highly evaluated in the United States and Europe. "[Being with Paro] probably stimulates the remaining healthy parts of the brain [in dementia patients] and calms them down," said Takanori Shibata, the senior AIST researcher who developed Paro. "I hope Paro will play a more important role in aging societies," he said. However, Paro costs about 400,000 yen per unit due to its complicated, high-performance technology. The price will have to be reduced if it is to be used more widely.

Graveyard Friends in Japan

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Community-based relationships and blood relationships are often neglected in modern society. Still, people need and want bonds. "I want to be buried when cherry blossoms swirl in the spring wind." "I don't want to be buried when it's hot." These words were overheard in a conversation between six men and women who have purchased or are planning to buy space in the same graveyard in Tokyo. They are dubbed "grave friends," and they got together at a May 10 meeting organized by the Ending Center, a Tokyo-based NPO to promote dignified death and burial. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 3, 2012]

“Most of the center members are people living alone, married couples with no children and those who do not want to be taken care of by their children. People make contracts with the Ending Center to make arrangements for their funerals, burials and other matters that must be taken care of after their deaths.

“I feel relieved now that I could say what was on my mind [for a long time]," said Sadako Nakao, 82, of Machida, western Tokyo, who purchased her space two years ago. Her husband died 13 years ago. Nakao does not know why, but she was able to say things she could not voice before to the people who will be buried in the same graveyard as her. Having lost her husband, she is preparing for her death alone. Sharing similar circumstances with others might be a factor behind her relief.

“Chiyo Yamane, 66, whose husband died 16 years ago, enjoys composing haiku poems and strolling with her "grave friends." Participating in the programs organized by the NPO is a major part of her life now, she said. "The superaging society is sustained by human bonds," Tsuji said. "Something must be done to create something to replace the bonds that are eroding.”

Image Sources: Ray Kinnane, Japan Zone, Andrew Gray Photosensibility

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013