RIGHT VERSUS LEFT IN JAPAN

Hagerty Incident in 1960, helicopter rescues American ambassador after protestors swarm around his car

The post-war period — particularly during the Cold war years — was characterized by a bitter ideological battle between the left and right that shaped the political climate and had a tremendous impact on the press. The left remained relevant as political force until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Japan became a key ally in the United States’s campaign against Communism. It was as close to the Soviet Union as Cuba was to the United States. The Soviet Union lobbied hard and put a lot of diplomatic pressure on the United States and Japan to keep the United States from bring nuclear weapons into Japan.

In Japanese education, pre-war hypernationalism was replaced by post-war communism, with students often taking the lead. Describing this period, the American diplomat Edward Seidensticker wrote in his memoir, “The world was divided between good guys and bad guys. The former were called peaceful and socialist, and their headquarters were in Moscow. This was before the break between China and the Soviet Union. The latter were the capitalist warmongers, and their headquarters was in Washington D.C.”

Good Websites and Sources on Post-War Japan : Wikipedia article on the Japanese Economic Miracle Wikipedia ; Jref Article on the Japanese Economic Miracle wa-pedia.com ; Long Blog Report on the Japanese Post-war economy dostoevskiansmiles.blogspot.com ; Yale Paper on the Economic Miracle econ.yale.edu ; Essay on Japan’s Rebirth at the 1964 Olympics aboutjapan.japansociety.org Wikipedia article on the Japanese Red Army Wikipedia ; Yukio Mishima's Suicide dennismichaeliannuzz.tripod.com/finalDay ; Wikipedia article on the Lockheed Scandal Wikipedia Post World-War-II Japan hartford-hwp.com Essay on Allied Occupation of Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on Postwar Japan 1952-1989 aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on 20th Century Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Birth of the Constitution of Japan ndl.go.jp/constitution ; Constitution of Japan solon.org/Constitutions/Japan ; Takazawa Collection at the University of Hawaii on Social Japanese Social Movements takazawa.hawaii.edu ; Documents Related to Postwar Politics and International Relations ioc.u-tokyo.ac.jp ; Japan Echo, a Journal on Japanese Politics and Society japanecho.com

Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Japanese History Documentation Project openhistory.org/jhdp ; Cambridge University Bibliography of Japanese History to 1912 ames.cam.ac.uk ; Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; WWW-VL: History: Japan (semi good but dated source ) vlib.iue.it/history/asia/Japan ; Forums Delphi Forums, Good Discussion Group on Japanese History forums.delphiforums.com/samuraihistory ; Tousando tousando.proboards.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MODERN HISTORY factsanddetails.com; OKINAWA, KAMIKAZES, HIROSHIMA AND THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AFTER WORLD WAR II: HARDSHIPS, MACARTHUR, THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION AND REFORMS factsanddetails.com; CONSTITUTION OF JAPAN (1947), ARTICLE 9 (THE NO-WAR CLAUSE) AND SHINZO ABE'S AMBITION TO CHANGE IT factsanddetails.com; JAPAN'S POSTWAR DEFENSE POLICY AND TREATIES WITH THE U.S. factsanddetails.com; JAPAN'S POST-WORLD-WAR II ECONOMY AND THE ECONOMIC MIRACLE OF THE 1950s AND 60s factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN THE 1950s, 60s AND 70s UNDER YOSHIDA, IKEDA, SATO AND TANAKA factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN THE 1980s AND EARLY 1990s: NAKASONE AND THE PRIME MINISTERS THAT FOLLOWED HIM factsanddetails.com; JAPAN BECOMES AN ECONOMIC POWERHOUSE IN THE 1970s AND 80s factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BUBBLE ECONOMY IN THE 1980s AND ITS COLLAPSE IN THE 1990s factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND ITS PRIME MINISTERS AND GOVERNMENT IN THE 1990s AND EARLY 2000s factsanddetails.com; KOBE EARTHQUAKE OF 1995 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Blood and Rage: The Story of the Japanese Red Army (1990) by William R. Farrell Amazon.com “Ashes to Awesome- Japan's 6,000-Day Economic Miracle” by Hiroshi Yoshikawa and Fred Uleman (2021) Amazon.com; “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century” by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert P Bix Amazon.com; “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John Dowser of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1999. Amazon.com; “Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power” by Sheila A. Smith (2019) Amazon.com; “Japan in Transformation, 1945–2020 by Jeff Kingston Amazon.com

Japanese Post War Politics

Assassination of Inejiro AsanumaThe post-war Japanese political scene was characterized by a domination of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), fights and shoving matches in the Diet (the Japanese parliament), and a debate between left-wingers proud of Japan's pacifist status and right-wingers who wanted Japan to be an economic superpower and regain its military strength. The conservatives also pressured the government not to fully apologize to other nations in Asia about atrocities committed in World War II.

The United States supported the LDP if for no other reason than to prevent leftists from coming to power. Japan supported the United States in all of its conflicts against communism. The arrangement suited Japan. While the U.S. took care Japan’s security needs the Japanese could devote their attention to creating industrial wealth and getting rich.

The LDP thrived under protection of the United States, and pushed its agenda “for “growth, growth, growth” and stamped out opposition. Buruma argued that dependency on the United States for defense “kept right-wing reactionism alive and polarized political opinion on the one thing where there should have been consensus: the Constitution itself.”

The LDP ruled all but 10 months between 1955 and 2000 either with an outright majority or with coalition partners. The fractious politics of the LDP hindered consensus in the Diet in the late 1970s. The sudden death of Prime Minister Ohira Masayoshi just before the June 1980 elections, however, brought out a sympathy vote for the party and gave the new prime minister, Suzuki Zenko, a working majority. Suzuki was soon swept up in a controversy over the publication of a textbook that appeared to many of Japan's former enemies as a whitewash of Japanese aggression in World War II. This incident, and serious fiscal problems, caused the Suzuki cabinet, composed of numerous LDP factions, to fall.

Left Wing Activism in Japan and Anti-American Demonstrations

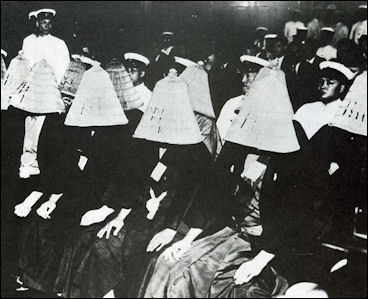

League of Blood IncidentIn the 1960s and 70s, there were anti-American demonstrations led by students who opposed to Japan's security arrangement with the United States and the use of American bases in Japan for the war in Vietnam.

In 1968, protests were held at 150 universities and violence spilled into the streets. The University of Tokyo was shut down for almost a year and didn't reopen until 8,500 club-wielding police burst into a university building and arrested 256 activists.

In the 1960s and 70s there were bomb attacks on industrial targets by left-wing groups. In 1974, left-wing radicals bombed a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries building, killing eight people and injuring 380 others.

Unrest and activism in the 1960s and 70s was a “broad-based swing to the left.” But in the end it was given a bad name by terrorist acts and was so “obliterated by the government and conservatism” that political activism never reared its head again after that.

Yukio Mishima

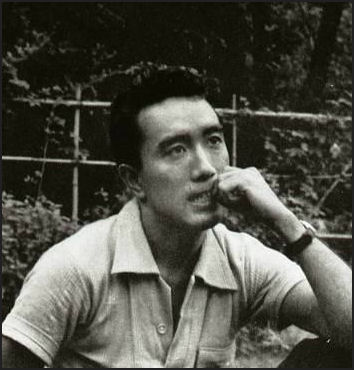

The flamboyant and controversial Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) is one of Japan's best known writers. Nominated twice for the Nobel prize, he wrote readable and entertaining novels but is remembered most for his shocking 1970 ritual suicide and the homo-erotic, military cult he created.

Mishima wrote 40 novels, including “The Temple of the Golden Pavilion”, about a novice monk who burned down Kyoto's famous Golden Temple in 1950; “Confessions of a Mask” (1949), a daring work which many regard as his best; and the “Sea of Fertility”, a tetralogy which includes “The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea” and was finished shortly before his death. He also wrote modernist noh plays, hundreds of essays and short stories, screenplays and film scripts for films he appeared in. Today there is also a Yukio Mishima literary award.

The son of a government official, Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka. As a child he was weak, sickly and effeminate and was often bullied by his classmates. He sought refuge in writing and reading and reportedly memorized a huge Kojien dictionary.

Mishima attended the elite Gakushuin Middle School in Tokyo. His mentor, Fumio Shimuzu, was a literature teacher there. Shimuzu created the pen name Yukio Mishima and greatly influenced Mishima’s style. Mishima studied law at Tokyo, took dance classes and enjoyed going to see kabuki and films.

Mishima's Nationalism

Mishima was as much a showman as a writer and he used his notoriety as a platform for "his showy style, dark homoeroticism, macho posturing and right-wing nationalism." He made a movie in which he acted out a ritual suicide in graphic detail and was featured in famous photo layout in Life magazine in which he wore only a loincloth and showed off his well-sculpted muscles and posed with a rose between his teeth.

After Mishima was rejected by the army he became a fitness fanatic, taking up boxing, kendo and bodybuilding and becoming a kind of alter ego to his sickly childhood self. After fulfilling a promise to his father by working in the Finance Ministry, a job he stuck with for only 9 months, he made a career out of writing. Shintaro Ishihara, a writer and friend who later became an influential politician and the mayor of Tokyo, said Yukio Mishima "had grown up with in a family of bureaucrats and underneath his pretensions he was conventional and inhibited."

Mishima was a fascist at a time when being a fascist was a bad career move. Surrounding himself in the 1960s with young men who embraced his cause as passionately as he did, he believed that Japan should reassert itself as a military power and re-embrace emperor worship. He wanted to use Japan's army to stage a coup d'etat and personally infiltrate youth groups to gather intelligence.

Ishihara's said Mishima was afraid to take his cause to the streets because he was worried about being “heckled and pelted with eggs." He described Mishima's patriotism as "aesthetic" and based on "romantic notions of loyalty, valor and the beauty of martyrdom."

Yukio Mishima's Suicide

One of biggest events in the 1960s period was the shocking 1970 ritual suicide of Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), a flamboyant and controversial writer, who was nominated twice for the Nobel prize, and launched a nationalist, homo-erotic, military cult.

Mishima On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four followers from his campy, private "army" of ultra-nationalist young men burst into the army headquarters in central Tokyo in an almost comical attempt at a coup d’etat. Dressed in a military-style tunic and rising sun headband, the 45-year-old writer stepped out onto balcony in the headquarters and gave a speech condemning Japan's pacifist constitution and told Japanese military personnel the time had come rise up and rebel and restore the honor of the Emperor. Most of those who heard him booed and shouted insults.

Mishima then barricaded himself in the commanding general's office, bound the general to a chair, and with the general looking on and shouting at him not to do it, Mishima plunged a 12-inch samurai dagger into his abdomen and disemboweled himself. One of his disciples drew an antique sword and, after failing twice, loped off his head in true samurai style and then took his own life. Everything except for failed attempt to remove his head on the first try had gone according to a meticulous plan and has been described as “one of the most sensational feats of exhibitionism of our age.”

Japan was left in a state of shock by the incident and the rest the world was not sure quite what to think. When Prime Minister Eisaju Sato was informed of Mishima’s suicide he called Mishima “insane.” Thousands attended Mishima’s funeral but soon after his death his army disbanded and several of his followers were imprisoned. "He became taboo in his own country," Donald Richie, a cultural critic and Mishima friend, told AP. "The accepted wisdom in Japan became that he was a minor figure, but that's not true. I think he's a strong influence, and a troubling one. He's like a bad conscience." In the 1990s, people once again began reading and discussing his work more openly.

See Arts and Culture, Literature

Japanese Red Army

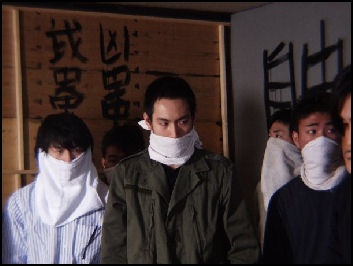

scene from the film United Red Army In the 1970s, the Japanese Red Army (JRA) was one of the world's most notorious terrorist groups. Initially a splinter group of the extreme left-wing United Red Army, the group was founded by Fusako Shigenobu in 1969 and was made up of radicals from student groups who protested the presence of U.S. military based in Japan. The goal of the group was to overthrow the Japanese government, eliminate the monarchy and foment world revolution.

In the early 1970s, the Red Army broke into factions. Shigenobu moved her faction to war-torn Lebanon and set up a commune, which allied itself with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and for fun held nightly self-criticism sessions. Pursued by Israeli agents they were constantly on the run. Even so Shigenobu had a daughter, with a Palestinian terrorist, who she raised with the help of other Red Army members and Arab supporters.

See Separate Article JAPANESE RED ARMY factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Kantei, office of Japanese Prime Minister; the film United Red Army by Koji Wakamatsu; Japan 101

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016