ASIAN ELEPHANTS IN INDONESIA

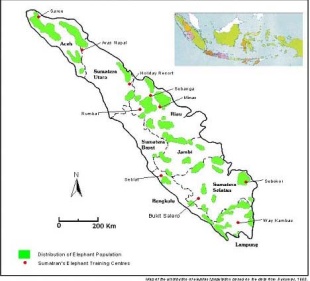

There are significant numbers of Asian elephants in Sumatra and some on Borneo. There are mainly found in dense forests on Sumatra. Most of those on Borneo are in Sabah in Malaysian Borneo. There used to be a lot of elephants on Sumatra island but are now they are rarely seen outside of logging sites or nature preserves. Domesticated elephants are occasionally used in logging or circus acts but many are unemployed or underemployed. Ones in Aceh found work after the tsunami towing damaged cars, moving debris and the like.

In Indonesia, there are two critically endangered elephant subspecies: the Sumatran elephant and the Borneo elephant. Sumatran elephants are found only on the island of Sumatra. Their estimated population of less than 1,500. Borneo elephants are Found in Kalimantan on Borneo.

Sumatra has one of the largest populations of Asian elephants outside India but their numbers are decreasing quickly,Threats to elephants in Indonesia include: 1) Habitat loss as a result of deforestation, palm oil plantations, timber concessions, mining, quarrying, and road building; 2) Poaching, the killing of elephants for their tusks or as a result of human-wildlife conflict. Elephants raid fields for food, which destroys people's livelihoods and they are sometimes killed for this reason.

Among the conservation efforts being employed are translocating elephants from degraded habitats to more suitable ones and habitat rehabilitation, which included fencing and restoring habitats. Community education involves teaching local communities about elephants and how to prevent conflicts.

Sumatran Elephants

The Sumatran elephant ((Elephas maximus sumatranus)) is one of three recognized subspecies of the Asian Elephant, and native to Sumatra Island. Among the Asian elephants, the Sumatran elephants are the smallest, with a shoulder height ranging between two meters and 3.2 meters (6.6 feet to 10.5 feet) and weigh between 2,000 and 4,000 kilograms (4,400 and 8,800 pound), and have 20 pairs of ribs. Their skin colour is lighter than of the Sri Lankan elephant and the Indian elephant even with the least depigmentation. Radio-collared Sumatran elephant clans in Aceh prefer areas of dense natural forests in river and mountain valleys at elevation below 200 meters (660 feet); from there, they moved into heterogenous forests and foraged near human settlements mainly by night. [Source: Wikipedia]

In 2011, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) moved the conservation status of the Sumatran elephant from endangered to critically endangered in its Red List as the population had declined by at least 80 percent during the past 75 years. Wild Sumatran elephants were once widespread on the island and formerly found in all eight provinces of Sumatra. However, the dense and tangled vegetation of the tropical rainforests there makes it difficult to estimate their exact number.

Sumatra’s Riau Province is believed to have the largest elephant population in Sumatra with over 1,600 individuals in the 1980s. In 1985, an island-wide rapid survey suggested that between 2,800 and 4,800 elephants lived in all of Sumatra in 44 populations. Twelve of these populations occurred in Lampung Province, where only three populations were extant in 2002 according to surveys done at that time. The population in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park was estimated at 498 individuals, while the population in Way Kambas National Park was estimated at 180 individuals. The third population in Gunung Rindingan–Way Waya complex was considered to be too small to be viable over the long-term.

Endangered Sumatran Elephants

It was estimated there were less than 700 wild Sumatran elephants left in 2021. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) raised the status of the Sumatran elephant from endangered to critically endangered in its 2012 Red List, mostly because of a 69 percent loss of potential habitat in 25 years. Indonesian forestry and environment ministry’s data showed the Sumatran elephant population has shrunk from 1,300 in 2014 to 693, down nearly 50 percent in seven years. There were an estimated 2,800 Sumatran elephants in 2007. Habitat destruction and poaching have been the main threats. [Source: Riska Munawarah, Associated Press, November 22, 2021; Jon Emont, New York Times, January 11, 2018]

By 2008, Sumatran elephants had become locally extinct in 23 of the 43 ranges identified in Sumatra in 1985 — a very significant decline. At that time they were locally extinct in West Sumatra Province and at risk of being lost from North Sumatra Province too. In Riau Province only about 350 elephants survived across nine separate ranges. As of 2007, there were estimated to be 2,400–2,800 wild Sumatran elephant, excluding elephants in camps, in 25 fragmented populations across the island. More than 85 percent of their habitat is outside of protected areas.[ [Source: Wikipedia]

In 2006, Michael Casey wrote in The Independent: “The number of Sumatran elephants in parts of Indonesia has dropped by 75 per cent in the past six years, raising the possibility they could become extinct in the near future, according to WWF Indonesia said, adding the decline in Riau province is mostly due to the rapid conversion of forest habitat into palm oil and paper plantations. As a result, conflicts between humans and elephants have risen, with 45 elephants either shot or poisoned between 2000 and 2005 and 16 people killed by the animals in that time. [Source: Michael Casey, The Independent, April 6, 2006]

“Hundreds more elephants were captured and removed from forest areas, often dying in captivity. The remaining populations number less than 400 in Riau, down from 709 in 1999. "This escalating situation not only spells disaster for elephants but is also a huge problem for Riau's local people," WWF said. "Without improved management, elephants could face extinction in another five years."

“WWF called on the Indonesian government to treble the size of the Tesso Nilo National Park to 100,000 hectares (247,100 acres) while increasing the number of teams that help avert conflicts between elephants and humans. A squad consists of four rangers and trained elephants who drive wild elephants back into the forest if they enter a village. “Wilistra Danny, chief of the government-run conservation board in the Riau town of Pekanbaru, agreed elephants were under threat and said the government was considering expanding the national park.

Elephants in Riau Province, Sumatra

Sumatra's Riau province is home to the largest elephant population in Indonesia but the animals are coming under threat as the forests that once covered the province are disappearing. In the 1990s and 2000s the paper and palm oil industries have cut down 60 percent of the elephant’s habitat. Now just 10 percent of the remaining forest is suitable for elephants. Since 1985, the province's elephant population has plummeted to 350 from 1,600. About 80 elephants live within Tesso Nilo National Park.

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In Sumatra, rampaging elephants that have wandered out of parks and into populated areas have long been shot or poisoned by officials or vengeful property owners. At least once a month, wild herds from the park attack one of the nearby settlements, activists say. Since 2007, 13 elephants and several residents have been killed in Riau province alone.” "If given a choice, elephants would prefer never to see humans," elephant hander Syamsuardi told the Los Angeles Times. "But the problem is that humans continue to invade their territory. There's not enough jungle left." [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, December 2, 2009]

“Syamsuardi has seen the results of their fury. Every few weeks, they rampage through settlements for food and out of anger or frustration. "The male pierces victims with its tusks and then throws them with its trunk. If they are still moving, he'll stomp them," he said. "Females mostly kick. Either way, it's a tragic way to die." They are also immensely powerful. An elephant can topple a pickup truck with one nudge of its forehead. In villages, the animals are referred to as datu, or mister, a term of respect given no other jungle creature.

Borneo Elephants

Borneo elephants (Elephas maximus borneensis) are also called Bornean elephant and the Borneo pygmy elephants. They are a subspecies of Asian elephant that inhabits northeastern Borneo, in Indonesia and Malaysia. Slightly smaller than other Asian elephants and known for their babyish faces, they are very gentle creatures and known for not being aggressive around people. It is become commonplace to refer to the Borneo elephant 'pygmy' elephants they are of similar size to elephants in Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra. Skull measurements of five adult female elephant from Gomantong Forest Reserve on Borneo were slightly smaller (72–90 percent) than comparable dimensions averaged for two Sumatran skulls.

Adult Borneo elephants are about to 2.45 meters (eight feet) tall, about 30 to 60 centimeters (a foot or two) shorter than mainland Asian elephants. They have a more rounded body, larger ears, a smaller face and a longer tails that reaches almost to the ground. They are less aggressive than their Asian cousins. They were found to be a distinct subspecies only in 2003, after DNA testing.

The origin of Borneo elephants is a a subject of debate and a detailed range-wide morphometric and genetic study has not been completed.

Some regard them as a distinct species from Asian elephants. Near all so them are in the far northern part of Borneo in Sabah. Because they are so remarkably tame and passive it was long thought that these elephants were descendants of domesticated elephants that had escaped or been set free in the forest. But DNA indicates that are genetically different from other Asian elephants and had been on Borneo at least since the last Ice Age.

About 1,000 to 2,500 elephants live on Borneo. In 2024, the Borneo elephant was listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List as the population has declined by at least 50 percent in past 60–75 years. It is mainly threatened by loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitat. The WWF wildlife group estimates that fewer than 1,500 Borneo elephants exist. Their numbers have stabilized in recent years amid conservation efforts to protect their jungle habitats from being torn down for plantations and development projects.

Tourist Killed by a Borneo Elephant

In December 2011, Associated Press reported: A Borneo elephant fatally gored an Australian tourist in a remote Malaysian wildlife reserve on Borneo island. Jenna O'Grady Donley died of injuries from the attack on Wednesday at the Tabin wildlife reserve, the first known fatal attack in Malaysia's eastern Sabah state, said the region's wildlife department director, Laurentius Ambu. The wild male elephant had been roaming alone around a mud volcano when Donley, a friend and their Malaysian guide saw it while trekking near their resort, Ambu said. [Source: AP. December 8, 2011]

Donley, 25, a vet, is believed to have gone within 10 metres of the animal, which might have charged at her because it was alarmed by the unfamiliar humans, Ambu said. Rangers had not seen the elephant but planned to drive it back into the forest, Ambu said. The elephant that attacked Donley is believed to have been a near-adult about 2 metres tall. Australia's foreign affairs department said the victim was from New South Wales. There were occasional elephant attacks in Sabah, Ambu said, usually if the animals were disturbed. This was the first incident of its kind at the Tabin reserve. People should remain at least 50 metres from wild elephants, he said.

Ten Dead Borneo Elephants Feared Poisoned

In January 2013, ten endangered Borneo elephants have been found dead in a Malaysian forest under mysterious circumstances, and wildlife officials said that they probably were poisoned. Sean Yoong of Associated Press wrote: “Carcasses of the baby-faced elephants were found near each other over the past three weeks at the Gunung Rara Forest Reserve, said Laurentius Ambu, director of the wildlife department in Malaysia's Sabah state on Borneo island. In one case, officers rescued a 3-month-old calf that was apparently trying to wake its dead mother.

Poisoning appeared to be the likely cause, but officials have not determined whether it was intentional, said Sabah environmental minister Masidi Manjun. Though some elephants have been killed for their tusks on Sabah in past years, there was no sign that these animals had been poached. "This is a very sad day for conservation and Sabah. The death of these majestic and severely endangered Bornean elephants is a great loss to the state," Masidi said in a statement. "If indeed these poor elephants were maliciously poisoned, I would personally make sure that the culprits would be brought to justice and pay for their crime." [Source: Sean Yoong, Associated Press, January 29, 2013]

The elephants found dead were believed to be from the same family group and ranged in age from 4 to 20 years, said Sen Nathan, the wildlife department's senior veterinarian. Seven were female and three were male, he said. Post-mortems showed they suffered severe hemorrhages and ulcers in their gastrointestinal tracts. None had gunshot injuries. "We highly suspect that it might be some form of acute poisoning from something that they had eaten,” Nathan said.

Palm Oil and Elephant Poisoning s in Sumatra

Gajah Makmur, an agricultural village in the hills of rural Bengkulu in Sumatra, has had to deal invasions by herds of displaced elephants. Jon Emont wrote in the New York Times: When wild elephants raided, villagers organized into brigades and used everything they could gather — pots and pans, a megaphone — to scare off the rampaging giants, forcing them to a palm oil plantation elsewhere.“It was just one example of how the rapid expansion of palm oil plantations into elephant territory here has brought humans and elephants into more frequent conflict, especially in remote villages far from ranger bases. Increasingly, that conflict is deadly. [Source: Jon Emont, New York Times, January 11, 2018]

Gajah Makmur is ringed by charred soil, as locals clear the surrounding rain forest to make room for a palm plantation. As a result of regional development, herds of displaced elephants have begun tearing into palm plantations at the edge of the village, damaging the crops and terrifying locals.” For some the answer has been to poison the elephants. For example, in the summer, Mawardi, a fisherman in Mekar Jaya, a nearby village, spotted two dead elephants on his way to the river. Elephants do not naturally die in pairs, so conservation groups immediately suspected that the deaths were the latest in a string of poisonings.

Investigators say elephant poisonings are particularly tricky to prosecute, because elephant killers are generally not repeat poachers, but instead ordinary farmers fed up with having elephants maraud their plantations. Villagers will always say they had no intention of killing the elephants, the poison was intended for wild pigs,” said Suwarno of Animals Indonesia. “It’s just an excuse the community can use to avoid a legal case.” Erni Suyanti Musabine, a forensic veterinarian employed by a government conservation unit in Bengkulu, regularly travels to remote stretches of rain forest to conduct elephant autopsies says her lab results regularly detect poison in the elephant carcasses,

In September 2006, seven Sumatran elephants raided a hamlet in the village of Padang Tambak in Lampung Province and damaged a house and destroyed 12 water pipelines, according to the report. A local villager told a radio station the attacks have frequently occurred. The incident is also blamed on severe loss of natural forest on Sumatra through legal and illegal forest conversion. Conservation group WWF-Indonesia said the conflict between homeless elephants and local people has reached crisis levels. WWF has documented that the population of elephants in Central Sumatra has declined from around 1,600 elephants in 1985 to 350 in 2003. [Source: Kyodo, September 30, 2006]

Elephant Poaching in Sumatra

Reporting from Calang in Aceh Province, Indonesia in 2021, Riska Munawarah wrote in Associated Press: An Indonesian court began a trial against a group of men accused of poaching endangered Sumatran elephants and trading in illegal ivory, in a case that wildlife conservation officials have hailed as a milestone. The case includes nine men accused of killing wild elephants by setting electrified wire traps on Sumatra, and two others accused of buying ivory from the elephant killings. The charges follow on the discovery by Indonesian authorities of five elephant skeletons in a village of the Aceh Jaya district in January 2020. The Aceh province’s conservation agency estimated that the group of elephants had been dead for more than two months before being found. A number of body parts, including their ivory tusks, were missing. [Source: Riska Munawarah, Associated Press, November 22, 2021]

Poachers prey on the endangered animals for their valuable tusks. State prosecutor, Achmad Buchori, told the Calang District Court that the defendants had intended to sell illegally the elephant tusks on the international market. “They have killed critically endangered animals viciously and brutally to earn money,” Buchori said, adding that they sold each of the elephant tusks for the amount of 3.5 million rupiah ($250). Under Indonesia’s Conservation of Natural Resources and Ecosystems, the group of 11 men faced up to five years in prison and a fine of 100 million rupiah ($7,000) if found guilty.

The trial opened a week after a baby elephant died after getting her trunk stuck in a poacher's trap. In July 2021, an elephant was found without its head in East Aceh. Police arrested a suspected poacher along with four people accused of buying ivory from the dead animal. Their trials began in October, 2021. “These trials send a strong messages that wildlife crime could not be tolerated and will be prosecuted at the court,” said Agus Arianto who heads Aceh province’s conservation agency. The number of Sumatran elephants that have died as a result of being snared and poisoning has reached 25 in nine years in East Aceh district alone, Arianto said.

Using Tame Elephants to Deal with Problem Elephants in Indonesia

Reporting from Tesso Nilo National Park, Indonesia, John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The wild bull elephant stood menacingly in the clearing, trumpeting in annoyance and anger, its brain racing with a chemical that unleashes a throbbing and unceasing headache. It was the heart of mating season, and the bull was desperately seeking a mate. Was this really a good moment to be sitting on top of another elephant just a few hundred feet away? [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, December 2, 2009]

But Syamsuardi, a native of the wild Sumatran forest, had his strategy ready: He would pit his own elephant against the amorous stranger. The compact 37-year-old, who like many Indonesians goes by one name, manages the Flying Squad, a herd of tamed elephants that patrols the more than 200,000-acre park like jungle Guardian Angels. Syamsuardi's team is the local brainchild of the World Wildlife Fund, which borrowed the idea from India. The goal: persuade the intruders to simply get lost, to return to their sanctuary, where lethal run-ins with humans are far less likely.

In 2004, after a rash of animal rampages, Syamsuardi began his monumental task: shape a team of wild animals into an obedient police force. Then a World Wildlife Fund outreach worker, he knew little about elephants. So he began reading up on the animals and working with them in the field. Now he and his staff of eight handlers foster a bond with their elephant wards. For mahouts such Adrianto, 26, it means a soothing voice interspersed with strict commands.

The team first tries to scare aggressive herds by setting off carbide cannons to scare them away. At night, rangers use car lights and blasts of the horn. But if these measures don’t work confronations sometimes becomes necessary. Syamsuardi recalled the terror of knowing he'd be exposed to piercing tusks and the collisions of gigantic bodies. Caught in the middle, he would be crushed like an insect. "It's tense, but you must be calm and stay quiet," he said. "I have to be ready to think quickly because when the time comes, my elephants are waiting for my command."

The mahouts treat obedient animals to brownies. But there are sticks that come with such carrots. When Ria resists, Adrianto whacks her hard on the head with a small stick with a metal end that he uses for discipline. Tesso gets a stick shoved into his ear when he gets too frisky. Before a routine patrol, Syamsuardi showered affection on Ria, rubbing her cheek and neck. He has grown to love these big animals and fears for their future."They're incredibly loyal," he said. "When a mahout falls during a fight with a wild bull, the herd will surround him in protection."

Methods Used by Indonesian Elephant Patrols

Describing the effort to contain the hyped up bull, John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Perched atop Rachman, the Flying Squad leader, he and the other mahouts, or handlers, positioned two males and two females side by side, never taking their eyes off the intruder. Then they moved slowly forward, a multi-ton battering ram, with each handler atop his elephant, awaiting the big bull's charge.

As the bull stomped in warning, the Flying Squad approached. The lineup, designed to confuse the invader so it can't tell which elephant is pack leader, came within a few feet. Finally, the bull lunged at Rachman. Tusks flashing, the two animals collided. Syamsuardi hung on as the other elephants closed in around the intruder, like a gang tackle on the football field. The fight lasted a tense and sweaty 35 minutes, during which the big animals swung their heads, bearing their tusks like swords, their bodies like battering rams. Finally, the bull moved off into the brush. "I was so satisfied. We didn't have to kill that bull," he said. "We just gave him a message: Go back to the forest with your own kind. You'll live longer that way."

Syamsuardi uses elephant face-offs as a last resort. And his methods have worked: So far, none of the mahouts have been hurt. With the Flying Squad, brute force isn't the only option. The team sometimes dispatches a female to mate with the aggressor, a tactic that has not only defused tension but also produced two offspring from the wild elephants: Tesso and Nella. If the mating option is used, the team finds a secure spot for the ritual, which can last a week. (The mahouts then get lost, to give the animals a little privacy.) If the team decides that it's better to make war, not love, fights between the Flying Squad and aggressors can last for hours.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025