MEGAPODES

Megapodes are birds in the family Megapodiidae with unusual nesting habits that live in tropical Australia, islands in the western Pacific, New Guinea, islands of Indonesia east of the Wallace Line and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. There are 20 species in seven genera and all, with the exception of malleefowl, are found in wooded areas such as rain forests or monsoonal scrub. Megapodes are threatened by humans. Adults are conspicuous, large ground-dwelling and easy to kill. The eggs are large, nutritious and easy to find. Several species are endangered.

Megapodes are also known as incubator birds or mound-builders. They are stocky, medium-large, chicken-like birds with small heads and large feet, hence their name. Megapode means “large-footed.” All are browsers, and occupy wooded habitats. Like chickens they spend most of their time searching for food by kicking their feet backwards and seeing what fruit, seeds and insects turn up.

Most megapodes are brown or black in color. They are superprecocial, meaning they hatch from their eggs in the most mature condition of any bird. They emerge from their shells with their eyes open, full wing feathers, and downy body feathers. They have the bodily coordination and strength to run, pursue prey. Some species fly on the day they hatch.

Species of Megapodes

Orange-footed scrubfowls (Megapodius reinwardt) are also known as orange-footed megapode or simply scrubfowl. They are chicken-size birds found in Australia and southeastern Indonesia that make nests out of sand and decomposing leaves and sticks that are 6.5 meters (20 feet) in diameter Heat generated by the decomposing material incubates the eggs.

Moluccan megapode (Eulipoa wallacei) are also known as Wallace's scrubfowl, Moluccan scrubfowl or painted megapode. They are small — approximately 31 centimeters long. They are the only species in the genus Eulipoa, but some taxonomists place them in the genus Megapodius, Both sexes are similar with an olive-brown plumage, bluish-grey bellies, white undertail coverts, brown irises, bare pink facial skin, bluish-yellow bills and dark olive legs. There are light grey stripes on reddish-maroon feathers on their back. Young have brownish plumage, a black bill and legs and hazel irises. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Mallefowl live in eucalyptus forest in southern Australia. They are territorial and maintains a mound of decomposing material throughout the year. They are stocky ground-dwelling birds about the size of a chicken. Their large nesting mounds are constructed by the males. Like other megapodes there is no parental care after the chicks hatch. Mallefowl are the only living representative of the genus Leipoa, though the extinct giant malleefowl was a close relative. +

Maleo Birds

Maleo are a species of megapode found in the forests of Sulawesi that bond for life and rarely wander more than a few meters from each other. Black and white in color, and frankly rather ugly, they are 55 centimeters (21.6 inches) long and weigh 1.5 kilograms (3.3 pounds), they lay large eggs in the ground near hot springs and act like a chickens. There are around 5,000 to 10,000 of them left. Maleo are threatened by loss of habitat and over harvesting of their eggs. [Source: Cannon ad in National Geographic]

Females maleo don’t stick around to care for their eggs or raise their young. They bury their eggs deep under the sand or rain forest soil, where the sun or geothermal heat keeps developing embryos warm. For about 70 days the egg incubates. When the egg hatches the chick digs its way out. [Source: National Geographic]

The problem that maleo birds have is that people often find their eggs and eat them. As of 2005, it was estimated that only 4,000-7,000 breeding pairs exist in the wild and these numbers are rapidly declining. Of the 142 known nesting grounds, only four are currently considered non-threatened. A large number of former nesting sites have been abandoned as a result of egg poaching and land conversion to agriculture.

The Wildlife Conservation Society and National Geographic have launched a program to preserve nest sites and transfer the eggs to guarded hatcheries. Between 2001 and 2007 more than 4,000 chicks were released in the wild. Since then efforts have been made to safeguard critical corridors between the nesting beaches and rain forest where the birds spend most of their time.

Megapode Nesting Behavior

Instead of laying eggs in conventional nests and incubating eggs in the conventional way, megapodes lay eggs in burrows or mounds and maintain the mounds in such a way that the temperature remains stable, using the sun, heat-releasing decomposed material or even geothermal heat.

Some of the mounds are quite large. The largest can be 11 meters in diameter and 4.5 meters high. These are generally composed of soil and leaf litter and are used year after year. Some megapods and scrubfowl work with other birds in the breeding season. Groups of these birds build ounds of leaves and decayed vegetable matter. As the vegetable matter rots the temperature rises. Females dig burrows in the mounds and lay their eggs in a stable environment that has a remarkable stable warm temperature between 35̊C and 39̊C.

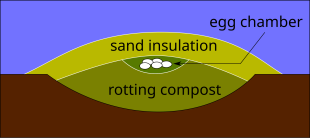

A typical megapode nesting mound has a layer of sand up to one meter thick used for insulation, an egg chamber, and a layer of rotting compost. The egg chamber is kept at a constant 33°C by opening and closing air vents in the insulation layer, while heat comes from the compost below.

Megapodes are mainly solitary birds. Their eggs are unusual in that they have a large yolk, making up 50 to 70 percent of the egg weight. Males and female may build the nest mounds together of decaying vegetation, but is usually the male builds the nest and maintains it by adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs develop. Not all megapodes do this. Burrow-nesters use geothermal heat; others simply rely on the heat of the sun warming the sand. Some species vary their incubation strategy depending on the local environment.

Nesting Behavior of Different Megapode Species

Orange-footed scrubfowl makes their nests out of sand and decomposing leaves and sticks. Heat generated by the decomposing material incubates the eggs. Maleo gather at communal nesting sites in the forest or on beach with geothermal activity or ample solar radiation and bury their eggs in a a deep holes to self-incubate in heated soil near hot springs, volcanic sand or beaches exposed to the sun. The collection of the eggs by humans used to be maintained under a system run by local sultans. After the power of the sultans was reduced the system fell apart and the eggs were overexploited and the birds became endangered.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the largest nest of any bird is made by the mallefowl. one specimen was 4.5 meters (15 feet) high and 11 meters (35 feet) across and required the moving of 880 tons of material. Eggs are laid from September to January in holes dug in the mound by the male, who covers the eggs with sand and maintains the mound so the temperature is always 33̊C (91̊F) by changing the depth of the sand.

On the island of New Britain there are populations of scrub fowl that have discovered sands that are kept permanently warm by hot gases and steams produced by volcanic activity. They lay their eggs in burrows there. On the island of Niuafo in Tonga, a species of megapode lays its eggs in hot volcanic ash.

Some smaller scrubfowl periodically stick their heads in the mound and check the temperatures with their tongue. If the temperatures are too cool they add leafy material. If the temperatures are too hot they take material away.

Megapode Chicks

Megapode chicks have a long incubation period (60 to 80 days). They usually break out of their thin-shelled eggs without the help of an egg tooth. After emerging from their eggs they lie on their back and use their oversized feet to dig out of the earth or leaf material that lies above it than sometimes is very thick. The process can take several days, with periods of intense activity broken up periods of long rest. The process is fueled completely by the yoke in the chick's stomach.

Megapode chicks emerge form their eggs with feet almost as large as their parents. Once they dig out of the nest, they immediately begin scratching for food. Within 24 hours their wings are developed enough so they can fly. When maleo chicks hatch and dig there way upwards. the emerge from the ground self sufficient and ready to fly.

The Australian brushturkey was thought to exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination like a reptile but was later shpwn to not be the case. Temperature however can affect embryo mortality and resulting offspring sex ratios. The nonsocial nature of their incubation raises questions as to how the hatchlings come to recognize other members of their species, which is due to imprinting in other members of the order Galliformes. Research suggests an instinctive visual recognition of specific movement patterns is made by the individual species of megapode. [Source: Wikipedia]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025