ETHNIC GROUPS IN INDONESIA

Indonesia is a culturally very diverse nation. There are thousands of ethnic identities in Indonesia and people identify quite strongly with their roots. In some areas of the country the conflicts between ethnic groups are quite pronounced and there has been violence. In Bali, the Balinese identify with their Balinese heritage above being Indonesian, as do the Javanese and Sundanese, and this appears to be norm for most groups regardless of the region or province of origin.

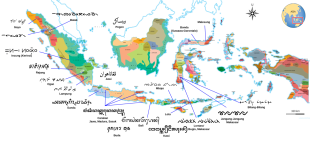

According to one count there are 336 ethnic groups in Indonesia, speaking more 700 languages, spread among 13,000 islands. By other counts there are more than 1,000 ethnic groups and subgroups. Because there are so many islands and on the islands the landscape is often very rugged, ethnic groups have developed in isolated spots. On the tiny island of Alor, for example, there are 140,000 people divided among 50 tribes, each of which speaks a distinct language or dialects that fall into seven distinct language groups. There About 350 recognized ethnolinguistic groups, 180 located in Papua; 13 languages have more than 1 million speakers.

Traveling from one island to another is often like going from one country to another. Often there is little to unite the people on one island with another. After independence in 1949, “Unity in Diversity” was adopted as a national slogan and was pushed on Indonesians. The only modern nation comparable in terms of multiplicity of ethnic groups, languages and religions is the former Soviet Union. Through the development of a national language, standardized education and persistent government propaganda, Indonesia has become surprisingly unified.

Nearly all of Indonesia are classified as “pribumi,” or “sons of the soil,” a term coined during Dutch colonial rule to designate “native Indonesians.” But many ethnic groups have never felt part of or represented by the Java-based government. Like many cultures in Africa, they were arbitrarily forged in a state by European colonial powers interested primarily in power and making money. When different groups are forced to live with each other they often judge one another by conflicting, homegrown customs. Even the nation motto is “Bhineka tanggal ika” (“they are many; they or one,” or “unity in diversity”) Indonesians often greet strangers with Orang apa?” ("Who are your people?") and “Dari mana” ("Where are you from?"), which can be both a friendly way to make conservation or a means of sizing someone based o their ethnicity. The term “bule” is often used to describe foreigners. It means white faces.

Ethnic identities are not always clear, stable (even for individuals), or agreed upon; ethnic groups may appear or profess to be more distinct socially or culturally than they actually are. But there are about 350 recognized ethnolinguistic groups in Indonesia, 180 of them located in Papua; 13 languages have more than 1 million speakers.

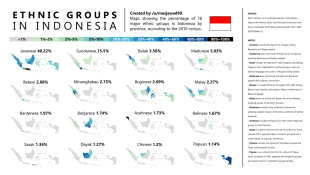

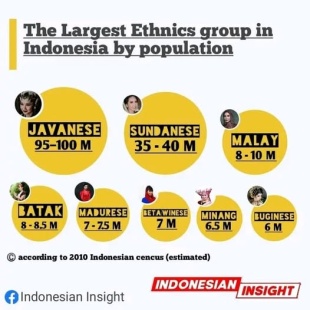

Largest Ethnic Groups in Indonesia

The Indonesian population is made up of 100 to 300 ethnic groups (depending on how they are counted) who speak around 300 different regional languages. Most of the people are of Malay descent. The Javanese are the largest ethnic group. Living primarily in the eastern and central part of Java. The Sundanese, who also live on Java, are the second largest group.

Major Ethnic Groups (Approximate percentages based on the 2010 and 2020 censuses):

1) Javanese: 40.1 percent - 42.65 percent

2) Sundanese: 15.4 percent - 15.51 percent

3) Malay: 3.45 percent - 3.70 percent, primarily on Sumatra;

4) Batak: 3.02 percent - 3.58 percent,primarily on Sumatra;

5) Madurese: 3.0 percent - 3.37 percent, primarily on the island of Madura and in eastern Java

6) Betawi: 2.51 percent - 2.88 percent

7) Minangkabau: 2.72 percent - 2.73 percent, primarily on Sumatra;

8) Buginese: 2.49 percent - 2.71 percent, primarily on Sulawesi

9) Bantenese: 2.0 percent - 2.05 percent

10) Banjar (Banjarese): 1.7 percent - 1.74 percent

11) Balinese: ~1.7 percent,primarily on Bali

12) Acehnese: ~1.4 percent, primarily in Aceh in northern Sumatra

13) Dayak: ~1.4 percent, primarily in Kalimantan;

14) Sasak: ~1.3 percent

15) Han Chinese: ~1.2 percent

16) Others: ~13.8 percent - 15 percent

In Indonesia, the concept of ethnic minorities is often discussed not in numerical but in religious terms. Although the major ethnic groups claim adherence to one of the major world religions (agama) recognized by the Department of Religious Affairs—Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism—millions of other Indonesians engage in religious or cultural practices that fall outside these categories. These practices are sometimes labeled animist or kafir (pagan). In general, these Indonesians inhabit the more remote, sparsely populated islands of the archipelago. Following the massacre of tens of thousands associated with the alleged 1965 coup attempt by “atheist” communists, mandatory religious affiliation became an even more intense political issue among minority groups. The groups described in the following sections represent a broad sample, chosen for their geographic and cultural diversity. [Source: Library of Congress *]

More than 14 percent of the population consists of numerous small ethnic groups or minorities. The precise extent of this diversity is unknown, however, because the Indonesian census stopped reporting data on ethnicity in 1930, under the Dutch, and only started again in 2000. In that year’s census, nine categories of ethnicity were reported (by age-group and province): Jawa, Sunda and Priangan, Madura, Minangkabau, Betawi, Bugis and Ugi, Ban-ten, Banjar and Melayu Banjar, and lainnya (other).

Characteristics of Ethnicity and Religion in Indonesia

Most of Indonesia’s many ethnic groups traditionally live in specific regions, especially in rural areas where people share the same language and customs. Greater mixing occurs in cities, border regions, and areas affected by migration and transmigration programs, particularly outside Java, such as in parts of Sumatra. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Ethnicity and religion are often closely linked. Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim population, and many ethnic groups are entirely Muslim. Dutch policies allowed Christian missionary activity among groups following traditional religions, leading to many ethnic groups today being predominantly Protestant or Catholic, especially in upland and eastern regions. Tensions can arise when people of one religion migrate into areas dominated by another. Over time, political and economic power has often become tied to both ethnicity and religion, as groups favor their own members.

Indonesians are mostly Muslims. Most ethnic Chinese are non-Muslim. They have traditionally controlled the businesses in Indonesia and still dominate some sectors of the economy. Among the more interesting ethnic groups are Dayaks (former headhunters on Kalimantan), the Asmet (former headhunters in West Papua that are similar to tribes in Papua New Guinea), the Toraja (a tribe on Sulawesi that has interesting burial customs) and the Sumbaese (a group that put dead relatives in their relatives in their living room for several years before they are permanently put to rest.

Diversity Among Indonesian People

Indonesia encompasses some 17,508 islands (some sources say 13,667 islands, other sources say as many as 18,000), of which about 6,000 are inhabited. Indonesia’s social and geographic environment is one of the most complex and varied in the world. By one count, at least 731 distinct languages and more than 1,100 different dialects are spoken in the archipelago. The landscape ranges from rain forests and steaming mangrove swamps to arid plains and snowcapped mountains. Major world religions—Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism—are represented, as well as many varieties of animistic practices and ancestor worship. [Library of Congress]

According to kwintessential.co.uk: 1) Each province has its own language, ethnic make-up, religions and history. 2) Most people will define themselves locally before nationally. 3) In addition there are many cultural influences stemming back from difference in heritage. Indonesians are a mix of Chinese, European, Indian, and Malay. 4) Although Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in the world it also has a large number of Christian Protestants, Catholics, Hindus and Buddhists. 5) This great diversity has needed a great deal of attention from the government to maintain a cohesion. 6) As a result the national motto is "Unity in Diversity", the language has been standardised and a national philisophy has been devised know as "Pancasila" which stresses universal justice for all Indonesians. [Source: kwintessential.co.uk]

Systems of local political authority vary from the ornate sultans’ courts of central Java to the egalitarian communities of hunter- gatherers in the jungles of Kalimantan. A variety of economic patterns also can be found within Indonesia’s borders, from rudimentary slash-and-burn agriculture to highly sophisticated computer microchip industries. Some Indonesian communities rely on traditional feasting systems and marriage exchange for economic distribution, while others act as sophisticated brokers in international trading networks operating throughout the world. Indonesians also have a variety of living arrangements. Some go home at night to extended families living in isolated bamboo longhouses; others return to hamlets of tiny houses clustered around a mosque; still others go home to nuclear families in urban high-rise apartment complexes. *

See Separate Article: INDONESIA: NAMES, FAMOUS PEOPLE, DIFFICULTY DEFINING IT factsanddetails.com

Unity Among Indonesia’s People

There are striking similarities among the nation’s diverse groups. Besides citizenship in a common nation-state, the single most unifying cultural characteristic is a shared linguistic heritage. Almost all of the nation’s estimated 240 million people speak at least one of several Austronesian languages, which, although often not mutually intelligible, share many vocabulary items and have similar sentence patterns. Most important, an estimated 83 percent of the population can speak Bahasa Indonesia, the official national language. Used in government, schools, print and electronic media, and multiethnic cities, this Malay-derived language is both an important unifying symbol and a vehicle of national integration. *

True to the Pancasila, the five principles of nationhood — namely Belief in the One and Only God, a Just and Civilized Humanity, the Unity of Indonesia, Democracy through unanimous deliberations, and Social Justice for all — Indonesian societies are open and remain tolerant towards one another’s religion, customs and traditions, all the while faithfully adhering to their own. The Indonesian coat of arms moreover bears the motto: Bhinneka Tunggal Ika – Unity in Diversity. [Source: Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia ^^^]

The society of many groups have traditionally been divided into three groups: nobles, commoners and slaves. Although slavery has formally been abolished it continues to exits as a social rank. To have a slave as an ancestor equates to low status. Adat (local customary practices) is supervised and administered by a headmen and elders. Sometimes it is codified like modern laws. But often each village has their own adat. Some Muslim groups practice female circumcision. Headhunting was practiced by many groups, particularly those on Borneo and West Papua.

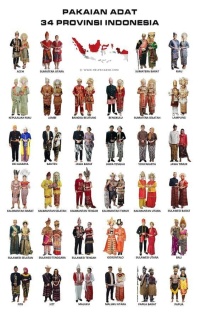

After Independence in 1945 inter-marriages among people of different ethnic groups became more common and this development has helped weld the population into a more cohesive Indonesian nation. Although today’s youth especially in the large cities is modern and follow international trends, yet when it comes to weddings, couples still adhere to traditions on the side of both the bride’s and bridegroom’s parents. So in a mixed ethnic wedding, the vows and wedding traditions may follow the bride’s family’s, while during the reception elaborate decorations and costumes follow the groom’s ethnic traditions, or vice versa. Weddings and wedding receptions in Indonesia are a great introduction to Indonesia’s many and diverse customs and traditions. Weddings are often also occasions to display one’s social status, wealth and fashion sense. Even in villages, hundreds or even thousands of wedding invitees line up to congratulate the couple and their parents who are seated on stage, and then enjoy the wedding feast and entertainment. ^^^

See Separate Article: PEOPLE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

History of Religion and Ethnicity in Indonesia

Indonesia’s variations in culture have been shaped by centuries of complex interactions with the physical environment. Although Indonesians in general are now less vulnerable to the vicissitudes of nature as a result of improved technology and social programs, it is still possible to discern ways in which cultural variations are linked to traditional patterns of adjustment to their physical circumstances. [Source: Library of Congress]

The majority of the population embraces Islam, while in Bali the Hindu religion is predominant. In areas like the Minahasa in North Sulawesi, the Toraja highlands in South Sulawesi, in the East Nusatenggara islands and in large parts of Papua, in the Batak highlands as well as on Nias island in North Sumatra, the majority are either Catholics or Protestants.[Source: Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia]

Although Islam is the main religion of Indonesia, it not practiced among many indigenous populations. During the 14th and 15th century. Muslim traders and sultanates expanded from west to east through Sumatra and Java, driving out Buddhist rulers and forcing Hindu leader to move to Bali, and then on to other islands. Islam remains strongest on the western side of Indonesia. Not surprisingly, Christianity later was able to make the greatest inroads in the east because Islam was not as firmly planted there.

Under Dutch rule, society was rigidly divided into Europeans, “foreign Asiatics” (including Chinese), Indo-Europeans, and native Indonesians. This system limited interaction between groups and discouraged assimilation. While it was partly intended to protect indigenous land from outsiders, it left Chinese communities isolated and with little incentive—or opportunity—to integrate into local society. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Jews in Indonesia

Indonesia’s Jewish community is very small — fewer than 200 practicing Jews. Many hope that interfaith events, such as a Passover celebration held in Jakarta, will help them gain greater acceptance and equal standing in the Muslim-majority country. [Source: Reuters, April 23, 2016]

Jews have lived in Indonesia since the colonial era. Dutch Jews helped develop the Spice Islands, and small Jewish settlements existed in Java and other islands by the 19th century. In the 1850s, visitors reported about 20 Jewish families in Batavia (Jakarta), along with others in Semarang and Surabaya. Most were of Dutch or German origin and had weak ties to religious life. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Later, Jews from Baghdad and Aden arrived, forming a more religious community. By 1921, there were nearly 2,000 Jews in Java. Many worked in government or trade, and Surabaya had an active Jewish population. Jewish numbers grew further in the 1930s with arrivals from Central Europe and Russia.

World War II and Indonesian independence led to a sharp decline. By 1957, the Jewish population had fallen to about 450, and by the 1960s it had dropped to fewer than 100. At the turn of the 21st century, only about 20 Jews remained in Indonesia, mainly in Jakarta and Surabaya.

Islamic Extremists Threaten Indonesia’s Minorities

In April 2016, about 15 men from the Islamic Jihad Front, a local hard-line group, forced their way into Lady Fast, a music event promoting female empowerment in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. They shouted insults, calling the women “communists” and “trash,” and demanded the event be shut down. A.Y., one of the organizers, told TIME by email that when she tried to calm the men as they ripped posters off the walls, one threatened her: “Do you want an argument or a debate? You’re a woman—easy enough to punch you.” [Source: Jonathan Emont, Time magazine, April 20, 2016]

Police were already at the scene, firing shots into the air to assert control. They did not arrest any of the hard-liners. Instead, they detained four Lady Fast organizers and participants, questioning them about the event and a book on LGBT rights found at the venue. A.Y. was frustrated. “It shouldn’t have been me taken to the police station, but the man who almost punched me,” she said. After explaining that the book had been there before the event began, she was released without charge a few hours later.

Yogyakarta is often celebrated as Indonesia’s bohemian university city, drawing students from across the country. Known for the arts and Javanese culture, it has also been promoted by the national government as a tourism hub. Recently, however, the city has also become a focal point for hard-line Islamist efforts to intimidate minority groups—including Christians, minority Muslim sects, progressive students, and the LGBT community. According to the Wahid Institute and the Legal Aid Institute, more abuses of minority rights have been recorded in Yogyakarta over the past two years than anywhere else except deeply conservative West Java. Incidents have included the burning of a Baptist church, attacks on Afghan Shi‘ite refugees, the blocking of a traditional ceremony for ethnic Dayak students from Borneo, and the forced closure of Pondok Pesantren al-Fatah, once the world’s only transgender Islamic boarding school.

“This is a significant shift in Yogyakarta, marked by growing intolerance,” says M. Najib Azka, a sociology professor at Gadjah Mada University, who blames the city government and police for failing to confront hard-line groups.

City authorities have long promoted Yogyakarta as the “City of Tolerance,” a slogan painted on murals across town. After the Lady Fast attack, a new progressive group, Solidarity for a Peaceful Yogyakarta, painted large question marks over the murals. That same question mark now looms over Indonesia more broadly. In 2014, Joko Widodo—widely known as Jokowi—won the presidency over Prabowo Subianto, who was backed by conservative and hard-line Muslim groups. Jokowi’s victory raised hopes that Indonesia would rein in ultra-conservatism.

Instead, incidents of intolerance have increased. The Setara Institute recorded 236 cases of religious violence in 2015, Jokowi’s first full year in office, up from 177 in 2014. Bonar Tigor Naipospos, the institute’s executive director, says Jokowi believes economic growth can solve most problems and lacks a strong grasp of human rights protections. “Too often, the police are simply silent,” he says.

The President’s Office declined to comment. Boy Rafli Amar, a spokesperson for the National Police, told TIME via WhatsApp that violent intolerance must be met with firm legal action and said such efforts were already under way. Participants in Lady Fast remain unconvinced. “When hard-line groups intimidated us, why were the organizers and participants detained?” asked Pamillia, who attended the event. “Why didn’t the police tell the hard-liners to leave?”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025