INDONESIA

The Republic of Indonesia is the the world’s fourth most populous country after India, China and the United States. It has roughly 285 million people (2025) — compared to around 200 million in 2000 — spread across nearly a thousand permanently inhabited islands. Its population encompasses two to three hundred ethnic groups, each with distinct languages and dialects, ranging from the tens of millions of Javanese (about 100 million) and Sundanese (about 40 million) on Java to small communities of only a few thousand on more remote islands.

Indonesia is the world's third-largest democracy after India and the United States and the world's largest Muslim nation., in terms of population, but it is also a secular state with sizable religious minorities. It is the biggest island nation on earth, composed of 17,000 islands where more than 300 languages are spoken. Though the Republic of Indonesia has only existed since 1949, Indonesian societies have a long history during which local and wider cultures were formed. Indonesia is a young democracy. It held its first direct presidential elections on July 4, 2004, six years after Suharto was overthrown. [Source: Hannah Beech and Muktita Suhartono, New York Times, May 21, 2019]

The main thing that links Indonesia's diverse territories and defines its border is that they were all part of the Dutch East Indies — a colonial entity largely consolidated by the early twentieth century, though Dutch involvement in the archipelago began in the seventeenth. Nationalism began to grow throughout the Indies in the second quarter of the twentieth century, and out of these diverse areas, religiously, ethnically, and linguistically, a single nation was born. Sukarno (1901–1970) proclaimed independence on August 17, 1945, at the end of World War II. However, the Indonesians were forced to fight and negotiate with the Dutch for four years before securing independence in December 1949. Like many Indonesians, Sukarno used only one name. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Indonesia’s national culture, like India’s, is profoundly multicultural. It is rooted in long-standing local societies and interethnic exchanges, but it also took shape through twentieth-century nationalist movements resisting European imperial rule. That colonial era, despite its inequalities, helped establish the territorial framework and many of the institutions inherited by the modern state. While the most visible expressions of Indonesian national culture appear in its cities, its influence increasingly extends into rural areas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVA MAN AND HOMO ERECTUS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER DUTCH RULE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

Names for Indonesia

Formal Name: Republic of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia). The the word Indonesia was coined from the Greek “indos”—for India—and “nesos”— for island). Short Form: Indonesia. Term for Citizen(s): Indonesian(s). Former Names: Netherlands East Indies; Dutch East Indies.

The term Indonesia was invented by James Richardson Loga in his study “The Languages and Ethnology of the Indian Archipelago” (1857). The name Indonesia was favored by anthropologists because it was similar to names given to neighboring cultural areas such as Melanesia ("black islands"), Micronesia ("small islands"), and Polynesia ("many islands"). In 1884, a German geographer named Adolf Bastian used the name in the title of his book Indonesien. In 1928, nationalists adopted Indonesia as the name of their of their hoped-for nation.

Indonesia used to called the Dutch East Indies and before that the East Indies and the Malay Archipelago. The term East Indies was first used to describe present-day India, Southeast Asia and Indonesia after Columbus called the islands on the Caribbean the West Indies.

The name “Indonesia” was officially adopted after Indonesia became independent in 1945 in part because it previous name, the Dutch East Indies, wouldn’t do. Indonesia can mean either “extended India” or “the islands of India.”

Diverse and Multi-Cultural Indonesia

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: ““Indonesia’s diversity is formidable: some thirteen and a half thousand islands, two hundred and fifty million people, around three hundred and sixty ethnic groups, and more than seven hundred languages. In this bewildering mosaic, it is hard to find any shared moral outlooks, political dispositions, customs, or artistic traditions that do not reveal further internal complexity and division. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

Java alone—the most populous of the islands, with nearly sixty percent of the country’s population—offers a vast spectacle of overlapping cultural identities, and contains the sediments of many world civilizations (Chinese, Indian, Middle Eastern, European). The Chinese who settled in the port towns of the archipelago in the fifteenth century are a reminder of the great maritime network that, long before the advent of European colonialists, bound Southeast Asia to places as far away as the Mediterranean. Islam is practiced variously, tinged by the pre-Islamic faiths of Hinduism, Buddhism, and even animism. The ethnic or quasi-ethnic groups that populate the islands (Javanese, Batak, Bugis, Acehnese, Balinese, Papuan, Bimanese, Dayak, and Ambonese) can make Indonesia seem like the world’s largest open-air museum of natural history.

“As Elizabeth Pisani writes in her exuberant and wise travel book “Indonesia Etc.” this diversity “is not just geographic and cultural; different groups are essentially living at different points in human history, all at the same time.” In recent years, foreign businessmen, disgruntled with rising costs and falling profits in India and China, have gravitated to Indonesia instead. About half the population is under the age of thirty, and this has stoked excited conjecture in the international business media about Indonesia’s “demographic dividend.” And it is true that in Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo, once known for its ferocious headhunters, you can now find gated communities and Louis Vuitton bags. But the emblems of consumer modernity can be deceptive. While Jakarta tweets more than any other city in the world, and sixty-nine million Indonesians—more than the entire population of the United Kingdom—use Facebook, a tribe of hunter-gatherers still dines on bears in the dwindling rain forests of Sumatra, and pre-burial rites in nominally Christian Sumba include tea with the corpse.

Not Even Trying to Define Indonesia

Elizabeth Pisani is the author of “Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation” (2014). She hasn’t even tried to “pin the vast archipelago nation down in a pithy manner”. “We don’t even know how many islands there are,” she told the New York Times. Some officials say 17,000; others, 15,000. “It’s an extraordinarily difficult thing for even its own government to get its head around, let alone an outsider like me.” Ms. Pisani made just one rule for herself during her many travels there: Say yes to any invitation, whether it was to a wedding or “to have tea with that dog liver and glass of rice wine,” she said. “That took me into very interesting directions.”[Source: Emily Brennan, New York Times, July 4, 2014]

On where to begin in a country as vast as Indonesia, Pisani told the New York Times: Java is a natural place to start. It makes up only 7 percent of the landmass, but is home to nearly 60 percent of population because the land is so fertile. The largest Buddhist temple complex on the island is Borobudur. Less well known, but every bit deserving of attention is another stunning complex of Hindu temples called Prambanan. Jakarta, the capital, used to be a few little islands of air-conditioned, steel-and-glass splendor that rose out of these rat-run back streets, little low-rise cobbled-together houses. Very neighborhoody. Now that’s almost all gone, replaced with a lot of marbled malls, 7-Elevens, high-rises, and everyone’s walking around with their iPad.

Where can you see a different side?: “There’s such wild diversity among the islands. The Banda Islands are relatively accessible (theoretically it’s a one-hour flight from Ambon, and if that’s canceled, a 10-hour overnight ferry), and they bring together the things that are really captivating about the country. There’s absolutely fantastic snorkeling and diving around the islands’ coral. And there’s history: It is where the colonial enterprise all started. They’re the only natural home of nutmeg, and the first of the Europeans to arrive there looking for this spice were the Portuguese, then the Spaniards, the Brits, then the Dutch. You can see this history just lying around. You can still see the Dutch East India Company logo on wrought-iron gates.

“Unfortunately, not much from the islands’ pre-colonial history has survived. There is, though, a tiny museum called Rumah Budaya Banda Neira, and they’ve made a real effort to present colonial history as it was experienced by the locals. One of the things the Dutch did in establishing their monopoly was genocide, and they did it with the help of Japanese samurai, and there’s a painting that depicts this.

What Is an Indonesian, Then?

Debate about the nature of Indonesia’s past and its relationship to a national identity preceded by many decades the Republic’s proclamation of independence in 1945, and it has continued in different forms and with varying degrees of intensity ever since. But beginning in the late 1990s, the polemic intensified, becoming more polarized and entangled in political conflict. Historical issues took on an immediacy and a moral character they had not earlier possessed, and historical answers to the questions, “What is Indonesia?” and “Who is an Indonesian?” became, for the first time, part of a period of widespread public introspection. Notably, too, this was a discussion in which foreign observers of Indonesian affairs had an important voice. [Source: Library of Congress *]

There are two main views in this debate. In one of them, contemporary Indonesia, both as an idea and as a reality, appears in some degree misconceived, and contemporary “official” readings of its history fundamentally wrong. In large part, this is a perspective originating with the political left, which seeks, among other things, to correct its brutal eclipse from national life since 1965. But it also has been, often for rather different reasons, a dominant perspective among Muslim intellectuals and foreign observers disenchanted with the military-dominated government of Suharto’s New Order (1966–98) or disappointed with the perceived failures of Indonesian nationalism in general. The foreign observers, for example, increasingly emphasized to their audiences that “in the beginning there was no Indonesia,” portraying it as “an unlikely nation,” a “nation in waiting,” or an “unfinished nation,” suggesting that contemporary national unity was a unidimensional, neocolonial, New Order construction too fragile to long survive the fall of that government. *

An alternative view, reflecting government-guided textbook versions of the national past, defines Indonesia primarily by its long anticolonial struggle and focuses on integrative, secular, and transcendent “mainstream” nationalist perspectives. In this epic, linear, and often hyperpatriotic conception of the past, Indonesia is the outcome of a singular, inevitable, and more or less self-evident historical process, into which internal difference and conflict have been absorbed, and on which the national character and unity depend. Some foreign writers, often without fully realizing it, are inclined to accept, without much questioning, the essentials of this story of the development of the nation and its historical identity. *

Both of these views came into question in the first decade of the twenty-first century. On the one hand, Indonesia’s persistence for more than 60 years as a unitary nation-state, and its ability to survive both the political, social, and economic upheavals and the natural disasters that followed the New Order, have driven many foreign specialists to try to account for this outcome. Both they and Indonesians themselves found reason to attempt a more nuanced reevaluation of such topics as the role of violence and the various forms of nationalism in contemporary society. On the other hand, a general recognition took hold that monolithic readings of Indonesia’s (national) historical identity fit neither past facts nor contemporary sensibilities. In particular, Indonesian intellectuals’ penchant for attempting to “straighten out history” (“menyelusuri sejarah”) began to be recognized largely as an exercise in replacing one singular perspective with another. Some younger historians have begun to question the nature and purpose of a unitary “national” history, and to search for ways to incorporate more diverse views into their approaches. Although it is still too early to determine where these realignments and efforts at reinterpretation will lead, it is clear that in contemporary Indonesia, history is recognized as a key to understanding the present and future nation, but it can no longer be approached in the monolithic and often ideological terms so common in the past. *

People in Indonesia

People in Indonesia are called Indonesians. People of Malay descent make up a large portion of the populations in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. The adjective Indonesian refers to the people of Indonesia, which is a relatively recent construct. Many people in Indonesia go by the island of their origin— Javanese, Balinese, Sumatran, Moluccan—or their ethnic group—Batak, Toraja or Sundanese. Some names like Madurese or even Javanese, refer to both an ethnic group and a people from an island.

Sixty percent of Indonesians live on Java and Bali, representing only 7 percent of the land area of Indonesia. Java has so many people that the population has already outstripped the availability of land and water and residents of the island are being encouraged to move to another island. As a result of an aggressive family planning campaign, the population is only growing at the rate of 0.95 percent, with a fertility rate of 2.18 percent (the fertility rate is the number of children per woman). The average life expectancy is 72 years. About 26.5 percent of all Indonesians are under 14, and 6.4 percent are over 65.

Indonesians over the years have been called “Indonesians,” Malay Islanders,” and East Indians.” Although there is great variety of ethnic groups in Indonesia today, the people of Indonesia are unified by national language, economy and religion. Some anthropologist distinguish three loosely-defined Indonesian cultures: 1) Hinduized societies that practice rice culture; 2) Islamized coastal cultures; and 3) remote tribal groups.

See Separate Article: PEOPLE OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Indonesians: Mostly A Malay People

Indonesians have traditionally been categorized as people of Malay stock. They are typically short (males average 1.5 to 1.6 meters in height) and have wavy black hair and a medium brown complexion. They are regarded as mix of southern Mongols, Proto-Malays, Polynesians, and in some areas, Arab, Indian or Chinese. The main non-Malay people are ethnic groups who live in West Papua (Irian Jaya, on New Guinea) and nearby islands. They are Melansian and related to people in Papua New Guinea and islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Some places such as Timor are regarded as Malay, Melanesian mix.

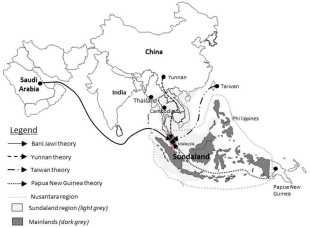

Malays evolved from the migration of people southward from present-day Yunnan in China and eastward from the peninsula to the Pacific islands, where Malyo-Polynesian languages still predominate.

The Malays arrived in several, continuous waves and displaced the Orang Asli (aboriginals) and pre-Islamic or proto Malay. Early Chinese and Indian travelers that visited Malaysia reported village farming metal-using settlements.

Combination of the colonial Kambujas of Hindu-Buddhism faith, the Indo-Persian royalties and traders as well as traders from southern China and elsewhere along the ancient trade routes, these peoples together with the aborigine Negrito Orang Asli and native seafarers and Proto Malays intermarried each other's and thus a new group of peoples was formed and became to be known as the Deutero Malays, today they are commonly known as the Malays.

See Separate Article: PEOPLE OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

More than 700 Languages Spoken in Indonesia

Indonesians speak hundreds of language. Depending on who is doing the counting they speak 583, 703 or 731 different languages. In one estimate 700 languages are spoken in Irian Jaya alone. On the tiny island for Alor, there are 140,000 people divided among 50 tribes, each of which speaks a distinct languages or dialect. Countries with the most languages: 1) Papua New Guinea (832); 2) Indonesia (731); 3) Nigeria (515); 4) India (400); 5) Mexico (300); 6) Cameroon (300); 7) Australia (300); 8) Brazil (234).

All people, except those in New Guinea and northern half of Halmahera, speak languages which belong to the related to the Malay-Polynesian group of languages, which in turn belong to the Austronesia family of languages, a group of agglutinative languages.. There are 1,200 Austronesia languages—about a fifth of the world's total. The Austronesian family extends from Malaysia through the Philippines, north to several hill peoples of Vietnam and Taiwan, and to Polynesia, including Hawaiian and Maori (of New Zealand) peoples. About a hundred different Austronesian languages are spoken on Vanuatu alone. Malay, Formosan, and most of the languages of Indonesia, the Philippines and Polynesia are Austronesia languages. Those that don’t speak Austronesian languages—people in parts of Timor, Papua, and Halmahera—speak Papuan languages.

There are many different regional languages and dialects. There are at least six distinct language groups on Sulawesi and seven on tiny Alor. The languages spoken in the interior of Kalimantan form their own distinct sub-family. On Java there are three main language. The Balinese have have their own language. Sumatra has around 52 languages. Acehese and Batak are the primary languages of northern Sumatra while Bahasa Melayu is the predominate language in the south. Mandarin is not only the most widely spoken language in China, it also has many speakers in Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

See Separate Article: LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Pancasila

Pancasila is a state ideology that appeared under Sukarno in 1945 around the same time he declared Indonesia’s independence and was pushed heavily during the Suharto years from the mid 1960s to the late 1990s. One of the primary goals of these two leaders was to create a national philosophy that would bind Indonesians together and prevent the country from fragmenting along regional, religious and ethnic lines.

Pancasila has been incorporated into the national coat of arm, which appears everywhere: on textbooks, in government offices, at police stations. Under Suharto it was regarded as so important that anyone who questioned it was in political hot water. Accusing someone of criticizing it is an effective way to discredit them.

The Five Pillars (“Pancasila”), and their symbols in the Indonesian coat of arms, are beliefs in: 1) one and only supreme god (symbolized by a star); 2) a just and civilized humanity (a chain); 3) the unity of Indonesia (banyan tree); 4) democracy is guided by inner wisdom of deliberation of representatives (buffalo head); and 5) social justice for all citizens of Indonesia (sprays of rice and cotton).

Some of the wording is deliberately vague and can be used both to support both democracy and autocracy. According to Pancasila any group that asserted itself to strongly was crushed and people could worship any of the major religions but were not allowed to be atheists. The first principal was attempt to come up an understanding that would include all major religions: Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism. Many Islamists saw it as a declaration for an Islamic state.

See Separate Article: GOVERNMENT, DEMOCRACY AND PANCASILA IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Traders in Indonesia

For centuries, trade has linked Indonesia’s many islands and connected them with regions far beyond today’s national borders. Local and foreign ethnic groups played important roles in these networks. Several indigenous peoples—including the Minangkabau, Bugis, and Makassarese—built strong reputations as traders, as did the Chinese. Bugis sailing vessels, still constructed entirely by hand and ranging from 30 to 150 tons (27 to 136 metric tons), continue to transport goods throughout the archipelago. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Trade between lowlands and highlands, and between coastal and inland areas, is sustained by these and many other small-scale traders operating within extensive market systems. Hundreds of thousands of men and women move goods using everything from human portage, horses, carts, and bicycles to minivans, trucks, buses, and boats. Islam spread along these same trade routes, and Muslim merchants remain deeply involved in small-scale commerce across Indonesia.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Dutch colonial authorities relied on Chinese intermediaries to connect rural farms and plantations to small-town markets, which in turn linked to larger towns and cities where Chinese and Dutch entrepreneurs dominated major commercial enterprises, banks, and transportation networks. As a result, Chinese Indonesians became a powerful economic force, today controlling an estimated 60 percent of national wealth despite representing only about 4 percent of the population.

Since independence, this economic prominence has contributed to government-led restrictions on Chinese ethnicity, language, schooling, and cultural practices, and has relegated those who sought Indonesian citizenship to a form of second-class status. Periodic violence targeting Chinese communities has erupted, particularly on Java. Meanwhile, many Muslim small traders—marginalized during the colonial era and initially hopeful after independence—grew frustrated as New Order political, business, and military elites forged lucrative partnerships with Chinese businessmen under the banner of “development.”

Famous Indonesians

Gajah Mada, the powerful prime minister under King Hayam Wuruk (reigned 1350–1389), succeeded in bringing much of the archipelago under the Majapahit Empire, creating one of the most extensive premodern polities in Indonesian history. Centuries later, Princess Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879–1904) emerged as a pioneering advocate for women’s emancipation. The school she founded for girls and her posthumously published letters, Door duisternis tot licht, attracted wide attention and made her an enduring symbol of female education and reform. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In the modern era, Indonesia’s political landscape has been shaped by a succession of influential national figures. Sukarno (1901–1970), a founder of the nationalist movement, became the foremost leader of the independence struggle and the country’s first president. Mohammad Hatta (1902–1980), a key architect of independence, served as Sukarno’s vice president as well as prime minister. After Sukarno’s fall, President Suharto (1921–2008) came to dominate Indonesian political and economic life for three decades (1968–1998).

Other major statesmen include Adam Malik (1917–1984), an internationally respected diplomat who helped repair relations with Malaysia, the Philippines, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the United Nations before serving as vice president (1978–1983); Umar Wirahadikusumah (1924–2003), vice president from 1983 to 1988; and his successors Sudharmono (1927–2006) and Try Sutrisno (b.1935). Following Suharto’s resignation in 1998, B. J. Habibie (b.1936) assumed the presidency, succeeded in turn by Abdurrahman Wahid (b.1940), Megawati Sukarnoputri (b.1947)—Indonesia’s first female president—and Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (b.1949), who began his term in 2004.

In the cultural sphere, many Indonesian artists have gained regional renown, but the painter Affandi (1910–1990) stands out as the country’s best-known artist internationally. Among modern writers, Mochtar Lubis (b.1922) is an influential novelist, while H. B. Jassin (1917–2000) is widely regarded as Indonesia’s most prominent literary critic. In the 1970s, the Indonesian thinker Soedjatmoko warned against the heedless technocracy that opened up massive disparities between the center and the periphery and rural and urban areas while destroying native self-confidence. “We will,” Soedjatmoko wrote presciently, “have to turn developmental thinking upside down.” [Source: Pankaj Mishra. Bloomberg, November 4, 2012]

Pramoedya Ananta Toer is Indonesia's best known novelist and arguably its most acerbic social critic. Nominated several times for the Nobel Prize for Literature and regarded as a kind of Indonesian version of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, he spent much of life in jail, including 14 years under Suharto and never won the Nobel Prize.. Under Suharto his books were banned and his personal library and archives were destroyed by government thugs. Pramoedya was born on February 6, 1925 and died on April 30, 2006. Despite missing the Nobel, his influential works, especially the Buru Quartet, garnered immense international acclaim, earning him major global literary honors and cementing his legacy as a voice for justice and decolonization.

Mata Hari (1876-1917) was one of the most famous courtesans of the Belle Epoque and the inventor of the striptease. Although she was a legend in her own time for these acts, what ensured her immortality was that she was convicted of treason and executed as a World War I spy. Mata Hari was born Gertrude Margarete Zelle. The eldest child and only daughter of dandified hat salesman, she was born and raised in a small farming town of Leeuwarden in northern Holland on August 7, 1876. Although her parents' families hailed from northern Germany and islands off of the Netherlands, Margartha had olive-colored, skin, brown eyes and black hair which later would help her convince the public that she a half-Indian, half-Indonesian temple dancer.

See Separate Article: factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025