YOGA IN THE WEST

Yoga took root in the West in the 1960s when eastern philosophy became popular with young people. As of 2010 there were 18 million practitioners in the U.S. and 500,000 in Britain. In the old days, teaching yoga was something that people did because they loved yoga and the basic, simplified lifestyle that went with it. Now there is a lot of money in it. [Source: The Times of London]

David Gordon White, a professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, wrote: “ Over the past decades, yoga has become part of the Zeitgeist of affluent western societies, drawing housewives and hipsters, New Agers and the old-aged, and body culture and corporate culture into a multibillion-dollar synergy. Like every Indian cultural artifact that it has embraced, the West views Indian yoga as an ancient, unchanging tradition, based on revelations received by the Vedic sages who, seated in the lotus pose, were the Indian forerunners of the flattummied yoga babes who grace the covers of such glossy periodicals as the Yoga Journal and Yoga International. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

Yoga became very popular in the United States and Europe in the early 2000s. Health clubs and corporate retreats began offering it. Trendy television characters such as those in Sex and the City did it. Vacations centered around it were offered in Turkey, Spain, Hawaii and Peru. Companies marketed sexy “chakra” tank tops, disco yoga and yoga gold classes. Television commercials featured people doing yoga in front of SUVs and yoga classes that promised to lift breasts and increase success in business. . Purists found all this to be a real turn off.

Websites and Resources: Yoga National Institutes of Health, US government, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Yoga: Its Origin, History and Development, Indian government mea.gov.in/in-focus-article ; Different Types of Yoga - Yoga Journal yogajournal.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga Wikipedia ; Medical News Today medicalnewstoday.com ; Yoga and modern philosophy, Mircea Eliade crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ; India's 10 most renowned yoga gurus rediff.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga philosophy Wikipedia ; Yoga Poses Handbook mymission.lamission.edu ; George Feuerstein, Yoga and Meditation (Dhyana) santosha.com/moksha/meditation

Yoga in the United States

More than 20 million Americans practice yoga. They do it in 100-degree rooms, swimming pools and on bikes. They do it to reggae music and to Christian prayers. You can buy yoga mats at the grocery store and find instructions on your airplane seatback. [Source: Jennie Yabroff, Newsweek, January 6, 2011]

Andrea R. Jain of Indiana University wrote in the Washington Post, Yoga has become more popular in the United States in recent years, with the number of people taking part in the discipline almost doubling between 2002 and 2012. Today, nearly 10 percent of Americans have tried it, and few of us have to travel farther than a neighborhood strip mall to practice our chaturangas. Yoga’s burgeoning trendiness isn’t restricted to the United States, either." [Source: Andrea R. Jain, Washington Post, August 14, 2015. Jain is an assistant professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and the author of “Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture”^=^]

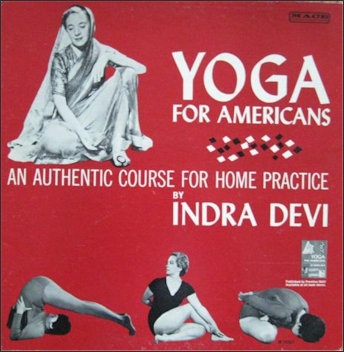

1963 album cover

In December 2011, "the United Nations declared June 21 the International Day of Yoga. The first celebration saw colossal gatherings of yogis worldwide, as hundreds, sometimes thousands, contorted their bodies into downward dogs and other poses en masse. Yoga has become one of the most fashionable practices in the world, yet a number of myths have grown up around it."

Tanya Basu wrote in The Atlantic, “Jain traces the Western fascination with yoga back to the 1960s, when a generation was hungry for a spirituality that was cleanly different from their parents’ more rigid religious beliefs. “Metaphysical religion is at least as important as evangelicism in shaping American religious history and in identifying what makes it distinctive,” she says, referring to studies by the religious scholar Catherine Albanese that found yoga to be a means by which traditional Christian thought could be blended with Eastern philosophy. Today, many Americans view yoga simply as a workout, which means that the practice has more or less been broken off from its millennia-old Hindu roots. [Sources: Tanya Basu, The Atlantic, January 12, 2015 ^|^

David Gordon White, a professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, wrote: “Statistics show that about 16 million Americans practice yoga every year. For most people, this means going to a yoga center with yoga mats, yoga clothes, and yoga accessories, and practicing in groups under the guidance of a yoga teacher or trainer. Here, yoga practice comprises a regimen of postures (āsanas)—sometimes held for long periods of time, sometimes executed in rapid sequence— often together with techniques of breath control (prānāyāma). [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

Debate in U.S. on Links Between Yoga and Hinduism

Tanya Basu wrote in The Atlantic, “A few years ago, yoga’s near-complete transition from spiritual practice to trendy fitness activity was marked by a spirited debate. Upset by yoga’s lack of religious connotation, Sheetal Shah, a senior director at the Hindu American Foundation, contacted the publication Yoga Journal asking why it had never linked yoga to Hinduism. She was told that Yoga Journal avoided the connection “because it carries baggage,” which prompted her to launch an initiative, called Take Back Yoga, to highlight yoga's Hindu roots. [Sources: Tanya Basu, The Atlantic, January 12, 2015 ^|^]

15th-16th century relief from the Achyutaraya temple in Hampi, Karnataka, India

“In response to Shah’s campaign, groups across the religious spectrum questioned whether there was a place in the ancient practice for yogis of other faiths and whether it was possible for any religion to “own” yoga. Others wondered if religious twists on yoga were contrary to the vision of Swami Vivekananda, the wildly popular monk who introduced yoga to the west and preached interfaith acceptance.^|^

“The Washington Post published a series of back-and-forths between one of Shah’s colleagues at the Hindu American Foundation and the physician Deepak Chopra. HAF board member, Dr. Aseem Shukla, and Chopra argued over yoga’s provenance. While the HAF maintained that the West ignores the connection between Hinduism and yoga, Chopra and many yoga instructors have pointed to the Sanskrit invocations peppered throughout a typical yoga practice as evidence that proper dues were being paid. Moreover, Chopra argued that the connection to Hinduism might be weaker than it is often presumed to be, seeing as the archaeological record suggests that yoga predates early Hindu scriptures.^|^

“Today, Shah says that “Take Back Yoga” is a misnomer. “We aren’t taking yoga ‘back’ from anyone,” she insists. She says she was simply interested in highlighting yoga's Hindu roots without insisting that it must be practiced by people of a certain religion. That said, she still cares deeply about the distinction between “true” yoga’s respect for the past and American yoga’s relatively superficial concerns. For Shah, the ultimate goal of yoga remains that of moksha, or spiritual liberation.” ^|^

Commercialization of Yoga in the United States

Yoga practitioners in the United States spend more than $10 billion a year on classes, clothing and accessories. Professor Jain told The Atlantic, “There is something about the United States that makes it a particularly booming hotspot for the contemporary yoga market.” She wrote in the Washington Post, “A typical studio class can cost more than $18, and a Lululemon outfit pushes $200. One of the most ubiquitous symbols of yoga’s commercialization is the mat, which many consider a necessity to prevent slipping, to mark territory in crowded classes or to create a ritual space. The most committed adherents can shell out more than $100 for a top-of-the-line mat. [Sources: Tanya Basu, The Atlantic, January 12, 2015 ^|^; Andrea R. Jain, Washington Post, August 14, 201.^=^]

“But these accessories are recent additions to the experience. The first purpose-made yoga mat was not manufactured and sold until the 1990s. Before then, yoga was practiced on grass, towels, rugs or bare wooden floors. Today, a small set of traditionalists refuses to use mats, arguing that they interfere with the practice, especially by distracting the yogi away from the true aims of yoga and toward the accumulation of commodities.^=^

“Some yoga advocates have rejected its commercialization by offering nonprofit classes and opening studios that spurn expensive accessories. Yoga to the People, for instance, offers donation-based classes in several cities, and part of its mantra is: “There will be no correct clothes, There will be no proper payment, There will be no right answers.” The company says the rising cost of yoga is at odds with its essence. Yoga is meant to help people become self-actualized, the company says — a priceless aim. Increasingly, yoga is also being introduced in marginalized communities, with classes taught in prisons, schools in low-income neighborhoods and homeless shelters. ^=^

Bastardization of Yoga

"doga"

Annie Gowen wrote in the Washington Post: “Indian yogic tradition appears in Hindu texts written thousands of years ago. But the discipline bears scant resemblance to the popular exercise regime that has become a multibillion-dollar industry in the West, home of $90 Lululemon stretch pants and Mommy and Me fitness classes.” There is “an ongoing public debate over the genesis of yoga and whether the bastardized and secular versions practiced in the West — nude yoga, rave yoga, kickboxing yoga — are even yoga at all. The discussion was fueled by The Washington Post’s On Faith blog in 2010, when a board member of the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) exhorted Hindus to “take back yoga and reclaim the intellectual property of their spiritual heritage.” Mega-guru Deepak Chopra fired back, saying that “yoga belongs to the whole world.” [Source: Annie Gowen, Washington Post, December 2, 2014]

White wrote: “ Yoga entrepreneurs have branded their own styles of practice, from Bikram’s superheated workout rooms to studios that have begun offering “doga,” practicing yoga together with one’s dog. They have opened franchises, invented logos, packaged their practice regimens under Sanskrit names, and marketed a lifestyle that fuses yoga with leisure travel, healing spas, and seminars on eastern spirituality. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

“In the United States in particular, yoga has become a commodity.“Yoga celebrities” have become a part of our vocabulary, and with celebrity has come the usual entourage of publicists, business managers, lawyers. Yoga is mainstream. Arguably India’s greatest cultural export, yoga has morphed into a mass culture phenomenon. Many yoga celebrities, as well as a strong percentage of less celebrated yoga teachers, combine their training with teachings on healing, spirituality, meditation, and India’s ancient yoga traditions, the Sanskrit-language Yoga Sūtra (YS) in particular. Here, they are following the lead of the earliest yoga entrepreneurs, the Indian gurus who brought the gospel of yoga to western shores in the wake of Swami Vivekananda’s storied successes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

Should Yoga Be Taken Seriously or Mocked

In a review of Claire Dederer’s book, “Poser: My Life in Twenty-three Yoga Poses”, Jennie Yabroff wrote in Newsweek, Apparently yoga is still exotic enough to be fodder for memoirs of the road to savasana—that’s corpse pose, or, for the uninitiated, lying on your back feeling grateful that class is over.” The yoga memoir feels much like any narrative of religious conversion, except that the yoga narrator freely mocks some aspects of the practice while adopting others. (It’s hard to imagine C. S. Lewis writing about his conversion to Christianity and making fun of the goofy priests and wacky incense.) Which is maybe the appeal of yoga: unlike traditional religions, yoga encourages a salad-bar approach, letting practitioners choose the parts they like (toned arms, instructors’ tendency to end classes by giving students mini head massages) and ignore the others (breathe through your perineum!). [Source: Jennie Yabroff, Newsweek, January 6, 2011 -]

US army soldier doing yoga

“There is much that is silly about yoga, and the effective yoga memoir first reassures the reader that the writer is not one of those spacey-eyed, splayed-hip nuts who is constantly tucking a foot behind her ear and says “namaste” instead of hello. Dederer immediately establishes herself as a relatable, down-to-earth narrator, a person who might kick up to headstand at a party, but only after a few drinks. -

“If you’ve ever done a downward dog on a sticky mat, you will laugh at her descriptions: the teacher who “looked as though she had been a step-aerobics instructor until five minutes ago” yet insists she’s called Atosa. (“Like hell you are, sister,” Dederer writes.) Or the instructor who liked to tell “humble little fables about monkeys and lions and tigers” in class, as though Dederer and her fellow Seattleites “all shared subcontinental Asian animals as our cultural touchstones.” Or the way that, despite the admonitions that yoga is a noncompetitive practice between you and your perineum, it’s impossible not to surreptitiously check out everyone else’s peaceful-warrior position. -

“Dederer names each chapter after a different pose, then explains what that pose means to her. Cobbler’s pose brings on an unexpected sobbing fit, and a memory of her daughter’s difficult birth. Camel pose creates “a fluttery, scary feeling” in her breastbone, which her teacher diagnoses not as a pulled muscle but fear. The chapters titled “Child’s Pose” tell the story of Dederer’s unconventional childhood: her mother left her father for a much younger man, but her parents remained married, sharing custody of her and her brother. Dederer says that yoga actually helped connect her own anxieties about motherhood to her ambivalence about her laissez-faire upbringing. -

“The link between infidelity, childbirth, and triangle pose is tenuous, but successful memoirs have been framed around less (Eat, Pray, Love, anyone?). The book’s weakness is the same one that plagues most yoga memoirs: the assumption that yoga is a kooky, cult-like practice, so what is such a nice girl doing in an overheated room of sweaty, chanting human pretzels? In truth, these memoirs are written by exactly the sort of person the modern American version of yoga is made for: secular, liberal, middle-class knowledge workers who want a workout but are also looking for something a little, you know, spiritual. A yoga memoir by a conservative Republican Catholic NRA member? Now that would be a real stretch.” -

American Yoga Market in the Mid-2000s

In U.S. the yoga has been stripped of its religious overtones and turned into a multi-billion dollar fitness industry. In 2006, Reuters reported: “Americans who practise yoga are often well-educated, have higher-than-average household income and are willing to spend a bit more on so-called "green" purchases seen as benefiting the environment or society. "It's kind of growing out of the crunchy stage of yoga to the Starbucks stage," said Bill Harper, publisher of Yoga Journal. "From the videos and the clothes and the toe socks...people are pursuing this market with a vengeance."

A glance through recent issues of his monthly magazine, whose readership has doubled in the past four years to 325,000, illustrates the point. There are four-color ads from the likes of Asics athletic shoes, Eileen Fisher apparel and Ford Motor Co. Yoga Journal is now licensing a Russian edition and preparing to expand in other international markets. [Source: Reuters, April 13, 2006 ==]

“Americans spend some $2.95 billion a year on yoga classes, equipment, clothing, holidays, videos and more, according to a study commissioned by the magazine, fuelled in part by ageing baby boomers seeking less aggressive ways to stay fit. Roughly 16.5 million people were practising yoga in the United States early last year, in studios, gyms or at home, up 43 percent from 2002, the study found. ==

“Established sellers of yoga gear such as Hugger Mugger and Gaiam have been flooded with competition in the market for yoga mats, incense, clothing and fancy accoutrements ranging from designer yoga bags to eye pillows. Vancouver, British Columbia-based Lululemon Athletica, for one, has seen sales of its yoga apparel rise to $100 million since Canadian entrepreneur Chip Wilson founded the company in 1998. Customers are snapping up its trendy pants and tops to wear to class and, increasingly, to the supermarket or out to dinner. The company operates some 40 stores, predominantly in Canada. It counts Japan and Australia among its new markets, and has a newly tapped management team that includes Robert Meers, former CEO of athletic shoe maker Reebok, to help set up shop in the United States. This month, Lululemon's reach extended to the US heartland, with the opening of a Chicago store. "A lot of investors are being attracted to the trend," said Corey Mulloy, a 34-year-old general partner with Boston-based venture capital firm Highland Capital Partners. Highland has stakes in Lululemon and Yoga Works, a growing chain of studios that boasts 14 locations in southern California and New York. ==

“Corporate types have indeed latched on. Rob Wrubel and George Lichter, best known as the men behind the Internet site Ask Jeeves, in 2003 provided refinancing for Yoga Works, which was founded in the late 1980s. Philip Swain, a former executive with national health club operator the Sports Club Co., now heads the company, which puts an emphasis on high-quality instruction and has grown by consolidating existing studios. Another expanding business, Exhale, markets itself as a "mindbodyspa," with tony locations in Los Angeles, New York and other urban areas that combine yoga classes with facials, massage and alternative treatments such as acupuncture. It lists nationally recognised yoga instructor Shiva Rea as "creative yoga adviser" and has backing from private equity firm Brentwood Associates. ==

“Some question how all the consumption is changing a discipline with a strong spiritual foundation. "We've taken this ancient tradition, science, and art of yoga out of a culture and a religion and world view and we've tried to transplant to the other side of the planet," said Judith Hanson Lasater, a longtime yoga instructor and author who holds a doctorate in East-West psychology. "I believe there's not a complete match-up." Even so, several entrepreneurs stressed that they are able to adhere to yoga's healing principles while also turning a profit. "It's about beauty and ascetics, not about opulence," said Joan Barnes, the former CEO and founder of children's apparel chain Gymboree, who runs a small chain called Yoga Studio in Northern California. For Cyndi Lee, 52, founder and owner of New York's City's popular Om yoga centre, the business remains a labour of love. Lee said she has turned down numerous buyout offers through the years, worried a loss of control could erode the sense of community she has helped to create. "It's not like McDonald's; it's not like popping out a hamburger," Lee said. "I don't want to have to commodify it."” ==

Indian View of the American Yuppie Yoga Scene

In 2008, Rupa Shenoy wrote in the Chicago Tribune, “I was at a swank party recently when a half-Indian, half-white friend pulled me across the room to join his conversation. He had mentioned to friends -- white friends -- that he had attended a yoga class and had been upset by the use of Hindu religious terms. They thought he was being touchy. They were making fun of him by chanting, "Namaste," and bowing mechanically from the waist. Besides mispronouncing namaste -- it's NUHM-us-thay -- the partygoers were using it the wrong way. It's a salutation, not a chant, and has gone out of style as too formal in many areas of India. I felt as my friend did -- uncomfortable in a way I could not put my finger on. [Source: Rupa Shenoy, Chicago Tribune, September 14, 2008 **]

“As an Indian-American, I accept that yoga has gone mainstream. Hinduism is an all-encompassing and welcoming religion that accepts even atheists. My problem is that there hasn't been a mainstream discussion about how tens of thousands of non-Hindus are practicing an art central to that religion while not always representing it properly. And there hasn't been much talk about how American yoga studios are making money from selling that religion. **

"Why I Quit My Yoga Class"

“Partially, that's the fault of American Hindus. We haven't really brought it up. Again, our religion is very accepting. But, generally, we don't really like to make waves. I found this attitude to be true among at least half of my extended family. That extremely unscientific sample divided into two groups: The immigrants don't think this is a big deal, but many of my fellow first-generation Americans have a small story of yoga outrage. My sister attends classes, but on her first visit, a religious faux pas was immediately apparent. A small statue of a Hindu god sat in front of the room. If my sister did the postures correctly, her feet would have pointed in its direction. In Hinduism, that's the highest symbolic gesture of disrespect. **

“This issue has been a big problem before. You might have heard about the flap in 2003 over American Eagle's selling of slippers with images of a Hindu god. That was outrageous enough to get even Hindus to protest. A cousin who grew up in America attended yoga-instructor training classes in New York taught by a "guru" who was supposed to be an authority. But when the teacher explained the philosophies of Hinduism, he got the basics wrong. And there are rights and wrongs. Though, like any religion, Hinduism is open to interpretation, yoga fundamentals are laid out in its most ancient texts. Most people in my cousin's classes didn't know that. **

“Though instructors who mention the complicated names of their swamis may want to impress their students, this does not indicate approval by a Hindu authority. Present-day Hinduism is incomprehensibly diverse. You can probably find a guru to back up virtually any assertion. It doesn't take much to call yourself a swami. In fact, there are lots of them back in India. The immigrants have a point, though. Yoga does a lot of good for a lot of people, and I'm glad that more people are discovering it. But my family's elders grew up in India, where they weren't minorities; most people around them were Hindu. They never needed to explain their religion to people, so they don't see why Hindus who grew up in this country might be more critical of how Hinduism is portrayed here. **

“As someone who has confronted caricatures of Hinduism all my life, including the turbaned bodyguard in "Annie" and Mike Myers in "The Love Guru," I'm a bit more protective and defensive. Though yoga is a part of Hinduism, it's just that: a part. We're talking about one of the world's ancient religions. There's a lot more to it, including the values and ethics that guide my life. Out of respect for those philosophies, I only wish people who pay money to experience my religion could know more about it. Or, I wish they could remember that yoga isn't just something taught in trendy studios -- it's part of a religion and culture that deserve respect.” **

Celebrity Yoga Instructors

Casey Schwartz wrote in Newsweek: “Marco, the tattooed instructor at the front of the room, is all charisma. He stalks; he pounces; he perches on my back as he corrects my Janu Sirsasana pose (otherwise known as a forward bend). “If you tell it to me from your mind, I’m not interested,” he announces, to begin the class. “That’s just drama. I’ve got my own drama.” It can be difficult to exit the studio when Marco’s class is over: people lingering to talk to him block the door. [Source:Casey Schwartz, Newsweek, February 20, 2011 /*/]

“Do yoga, transcend your ego, and discover your inner humility—at least that’s the idea behind this ancient spiritual practice. The enlightened person is “friendly and compassionate, free from self-regard and vanity,” promises the Bhagavad-Gita. But in the recent past, around the time that $100 yoga pants became as common as designer jeans, the once inconspicuous yoga instructor has morphed into something more grandiose. Now certain teachers display all the monkishness of Keith Richards cooling his heels in the greenroom as adoring fans reach a peak of anticipation. /*/

“The aura of high priest surrounds not just celebrity instructors like Marco, who teaches at Pure Yoga, and is known throughout the New York yoga scene for his godlike presence, but the ranks of proletarian instructors as well. The New York City–based filmmaker Ariel Schulman goes to a weekly class at Kula in Greenwich Village. He knows the instructor is in the building when he arrives. “But she comes into class late. She waits for the room to fill up—I feel the drumroll, sitting cross-legged waiting for her—and she makes her grand entrance.” The lights dim, and her patter begins: “Who don’t I know?” she asks. “Who haven’t I met?” /*/

“In America, yoga has become a mainstream and marketable cult—20 million people practice regularly, according to some estimates—and its teachers are, in a sense, performers. That’s why the narcissistically inclined can be drawn to the job, says Miles Neale, a Buddhist psychotherapist based in New York. Becoming a yoga teacher allows an insecure person to act spiritually superior. But the dynamic is two-sided. For the yoga teacher to become inflated, the student must inflate. Yoga acolytes, like rock-band groupies, hang on the approval of their favorite gurus—thus allowing that narcissism to flourish. “People elevate because they want to be accepted by the one that’s elevated,” Neale says. “That makes them feel good.” /*/

“Some yoga-diva antics would be considered bad manners even in Hollywood. Jennifer Needleman, a film editor, woke up before dawn recently to attend a new class at her local Venice, Calif., yoga studio. So few students showed up that the teacher declined to teach. It simply wasn’t worth her time, she said. Matt White, a member of the L.A.-based band Earl Greyhound, remembers resting on his back at the end of one class when the instructor seized the chance to burst into song. “I could be wrong, but I swear to God, he was singing something from a musical, like from Pippin,” says White. Carrie Campbell, a Pilates instructor in New York, was midpose at the notoriously purist Jivamukti studio, when her instructor approached, paused, and sniffed. “I can tell by the smell of your sweat that you’re not a vegetarian,” she announced for the whole class to hear. Campbell has not returned since. /*/

“Instructors concede that there’s a lure to giving in to their egotistical impulses. “When I start to feel powerful—that’s a dangerous place to be,” says Emily Wolf, a yoga instructor who is also studying to be a psychologist. When she begins to feel that way, she remembers her own teachers “who continue to put me in my place,” she says. The megalomaniacs, she believes, have lost sight of the fact that they were ever students themselves.” /*/

Attempts in the U.S. to Patent and Regulate Yoga

Mr yoga asana (posture): the reverse facing stretch

In the United States, as far a yoga is concerned, business rights often have precedence over religious ones. The U.S. Patent Office has granted numerous patents for yoga-related products but maintains that it has not given out patents for yoga routines. As of 2007, US authorities had issued 150 yoga-related copyrights, 134 patents on yoga accessories and 2,315 yoga-related trademarks. [Source: Jeremy Page, The Times of London, May 31 2007]

New York and Virginia have proposed legislation to regulate yoga. These moves have not been greeted warmly by yoga teachers. Edith Honan of Reuters wrote: “About 50 yogis gathered in New York recently to discuss hiring a lobbyist and raise funds to fight a state proposal to require certification of yoga teacher training programs -- a move they say would unfairly cost them money. "It has brought us under one roof," said Fara Marz, who held the gathering at his Om Factory yoga studio in New York. "And this shows that yogis can be vicious, political, together." Yoga enthusiasts who say autonomy is fundamental to what they do are pitted against state governments eager for a slice of” the multi-billion dollar yoga industry. The fight has underscored the difficulty of regulating yoga studios that have become ubiquitous on Main Streets and in gyms across the country without appearing heavy-handed or infringing on religious freedom. [Source: Edith Honan, Reuters, September 2, 2009 =]

“New York's yoga instructors first attracted the state's attention, when the education department announced training schools could face up to $50,000 fines if they did not submit to state regulation that governs vocational training. After protests from yoga proponents, the education department withdrew its plans. Perhaps yogis can breathe easily in New York. The state legislature is considering a bill that would exempt them from vocational school certification. "The message from the community has been loud and clear: get your government hands off my yoga mat," State Senator Eric Schneiderman said in a statement. "Next time, the state will think twice before threatening a practice that brings so much tranquility to New Yorkers." =

“Meanwhile, in Virginia, yoga training programs are fighting a directive that they submit to oversight. All 50 U.S. states require vocational schools to meet certification standards and many charge a registration fee for schools to maintain certification. But according to the Yoga Alliance, only 13 states actively enforce those requirements for yoga teacher training programs. Yogis say their industry does need some regulation but are divided as to whether they can regulate themselves. "Yoga seems to be popping up on every single street corner and what we're concerned about is that they're teaching good yoga, ethical yoga -- as opposed to, some people are only in it for the money," said Mark Davis of the Yoga Alliance. The Virginia-based nonprofit group keeps a voluntary yoga school registry and their standards are now the industry benchmark. "There have been consumer complaints to state agencies because of unethical behavior and there was no recourse because the school wasn't licensed," Davis said. =

“In New York, many yogis say the state has no business telling people how to practice yoga. Marz, who also heads an architecture firm, said many yogis were reluctant to form associations and spend money on lobbyists and lawyers. "Most of the people who open yoga studios, they did it because yoga changed their lives and they want to share it. They don't realize that such an incredible, complete beast is waiting there for them," he said of state regulations.” =

India Angry Over U.S. Attempt to Patent Yoga

Is it possible to patent this asana --- the Mr Yoga mountain pose

Jeremy Page wrote in The Times of London, “The Indian government has worked itself into a furious twist over efforts by American entrepreneurs - including an Indian-born celebrity 'yogi' - to patent the ancient practice.” In May 2007, “Indian officials announced that they would lodge official complaints with US authorities over hundreds of yoga-related patents, copyrights and trademarks that have been issued in recent years. The Health Ministry said it would take up the matter directly with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, while the Commerce Ministry said it would write to the US Trade Representative. "How can you patent yoga - something that has been in the public domain for thousands of years?" said Verghese Samuel, joint secretary of the Ministry of Health. "It's a ridiculous decision. We'll have to challenge it. We've already started the process." [Source: Jeremy Page, The Times of London, May 31 2007]

The dispute has exposed the differing attitudes towards yoga - and intellectual property rights over traditional knowledge - in India and the US. In India, where yoga has been practiced for 6,000 years, it is regarded as a Hindu exercise, involving philosophy as well as fitness, and beyond the control of government or private enterprise.

Indian authorities were particularly angry by the copyrights and trademarks granted on yoga poses. Meena Hartenstein of ABC News wrote: “In response to reports that the United States had granted a patent to a yoga instructor, several members of the Indian parliament took to the media and blasted the U.S. Patent Office for giving out patents on yoga products and teaching methods. "We have had yoga for 5,000 years. It is not proper for anyone to give out patents on yoga," Vijay Kumar Malhotra, spokesman for the Indian parliament's Bharatiya Janata Party, told ABC News. [Source: Meena Hartenstein, ABC News, May 22, 2007]

Vinod Gupta, head of the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library, an electronic encyclopedia of India's traditional medicine, and his team are cataloging all of India's ancient knowledge on medicine to prevent individuals in other countries from patenting drugs or remedies that have existed in Indian culture for centuries. The library was created in 2001 after India won its first patent battle against the United States. The United States had given out a patent on turmeric -- an ancient Indian medicinal remedy -- and India succeeded in having the patent revoked.

Gupta and the Indian government” are “focused on their goal” of protecting “yoga as an Indian invention. Gupta said he believes that by issuing patents, the U.S. government may be allowing individuals to restrict the practice. "No one is against Bikram making money, but he shouldn't stop others from teaching yoga. We are not saying that you cannot perform yoga until you pay the government of India. We are saying, yoga belongs to our culture. It's our heritage," he said. "We want the system of knowledge that is India's to be available to everyone but not appropriated to a few."

Bikram Choudhury’s Attempt to Patent Yoga Poses

Indian authorities were particularly upset by trademarks granted to Bikram Choudhury, the founder of 'Hot Yoga' for his brand of 26 yoga poses performed in a steam room. The Bikram Yoga brand has made Choudhury something of a celebrity -- his studios are all over the country, he sprinkles conversation with the names of A-list clients and friends like Quincy Jones and Shirley MacLaine, and his brand of yoga is practically a household name. Every year he reaps the profits from his best-selling books, videos and exclusive line of yoga clothing.

Meena Hartenstein of ABC News wrote: “The Indian media has swirled with rumors that parliament is specifically targeting Bikram Choudhury, arguably the best-known yoga patent holder in the United States. Choudhury, who was born in Calcutta but now lives Los Angeles, built his Bikram Yoga empire on a series of 26 carefully choreographed asanas, or yoga positions, performed in a heated room and accompanied by a specific set of instructions. All of this, according to Choudhury, is patented, copyrighted and trademarked. "I have a brand name," he said. [Source: Meena Hartenstein, ABC News, May 22, 2007]

“Yet despite the notoriety, or perhaps because of it, Choudhury is a divisive figure in the yoga world. Indians argue that he has stolen their ancient traditions and is now profiting from them, while Choudhury believes he is entitled to protect his style of yoga since he created it. "No one in the world does yoga the way I do -- not even in India," he said. Vinod Gupta, head of the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library, sees it differently. "It is not his own," said Gupta. "Those asanas were created in 2500 B.C."

“The U.S. Patent Office said Choudhury does not hold a patent on his Bikram brand of yoga, but he does have patents on related products. And the routine itself is protected by a copyright, and since he also holds a trademark on his sequence of moves, he controls how Bikram Yoga is marketed and sold. None of these legal protections allow Choudhury to "own" his routine -- people are still free to practice it in the park, for example. But no one can market themselves as a licensed Bikram practitioner without his OK . Despite the brewing controversy, Choudhury said he remains unfazed. He believes that rather than trying to block him from making money, India should focus on making its own profits from yoga. "Yoga is a multimillion dollar industry," he said. "How much has India made out of it? Nothing. I think they are a little bit jealous."

Bikram Choudhury leading a yoga class

Celebrities Who Do Yoga

Among the celebrities that swear by yoga are Jude Law, Angelina Jolie, Ricky Martin, Kate Moss, Hilary Clinton, Sting, Meg Ryan, Stephen Spielberg, Dennis Quaid, Woody Harrelson, Gwentyth Paltrow, Christy Turlington. Kareem Abdul Jabaar, Julia Roberts, Shirley MacLaine, Raquel Welch, Uma Thurman, Penelope Cruz, John Cusack, the Beastie Boys, Sean Connery, Barbara Walters and Marisa Tomei.

Courtney Love, Madonna, Cindy Crawford, David Duchovny and Rosana Arquette are into Kundalini yoga. Candice Bergen, Rachel Weisz, Ashley Judd, and Brooke Shields like Bikam yoga. For a while former United States Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Conner took regular classes.

Those mentioned on a BuzzFeed list included Charlize Theron, Demi Moore, Reese Witherspoon, Naomi Watts, Robert Downey Jr), Vanessa Hudgens, Colin Farrell, Emily Blunt, Gavin Rossdale, Ali Larter, Alessandra Ambrosio, Adam Levine, Jennifer Aniston, Ashley Tisdale, Jeremy Piven, Renee Zellweger, Heather Graham, Melanie Griffith, Russell Brand, Kate Hudson, Shenae Grimes, Zachary Quinto, Hilary Duff, Kirsten Dunst, Lisa Rinna, Matthew McConaughey, Helen Hunt, Ashley Olsen, Orlando Bloom, Jenna Tatum-Dewan, Jessica Biel, Nicole Kidman, Ellen Pompeo, Halle Berry, Russell Simmons, Olivia Wilde and Gisele Bundchen. [Source: Emily Hennen, BuzzFeed, February 19, 2014]

Books about Yoga in America

"The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America," by Stefanie Syman (Farrar Straus Giroux, $28). Stefanie Syman begins by noting that the 2009 Easter Egg Roll was likely the first time yoga had been practiced on the White House lawn. A century earlier Americans widely believed that yoga "perverted one's moral sense" and "was about as useful as malaria or consumption but far easier to avoid." Syman traces the evolution of yoga through the stories of its notable practitioners, such as Thoreau, Margaret Woodrow Wilson and, yes, Madonna. [Source: Stephen Lowman, Washington Post, July 18, 2010 +++]

"The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America," by Robert Love (Viking, $27.95) Robert Love writes in his introduction that he had assumed the Beatles were responsible for popularizing yoga. In fact, he reports, it was the Iowa-born businessman and mystic Pierre Bernard (nicknamed "The Great Oom") who helped bring it to the masses. Love details Bernard's strange exploits -- such as the secretive Tantric ceremonies held at his clinic -- as he successfully packaged and sold yoga to skeptical consumers. +++

"Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice," by Mark Singleton (Oxford Univ.; paperback, $17.95). The most academic of the three books, "Yoga Body" is for those with a serious interest in yogi philosophy. Mark Singleton argues that yoga as practiced in the Indian tradition had to do more with purification and meditation than with the health and fitness aspects that have made it all the rage today. +++

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018