YOGA

Vijay Krishna GosvamiYoga is a form of expression that has taken many forms over the years and often involves stretching or holding certain poses, deep breathing and meditation with aim of achieving physical, mental and spiritual wellness. Its origins lie within Hinduism. According to some Hindus it began as an effort to reverse creation and return to the perfect Oneness from which the world fragmented — with the goal of "freeing the individual from illusion and achieving union with Brahma." The physical aspects of yoga are not an end to themselves but are an aid to “inner purification” aimed at “the dissolution of the ego." The goal is samadhi, a union with nature and the consciousness of God.

Yoga means "union" in Sanskrit and has eight different elements of which hatha yoga (physical or active yoga), which Westerners most often use, is just one. Others include karma yoga (following a path of righteous action), raja yoga (meditation and concentration on the infinite), jnana yoga ( pursuit of mystical knowledge), siddhi yoga (awakening of mystical energies), and Shakti yoga (pure faith in a supreme being).

In India, the practice of yoga is based on a comprehensive philosophy of man striving for harmony with himself and the world and encompasses breathing, meditation and exercise. In Western countries, it is associated most with the practice of asanas (postures). Some Yoga-like exercises are designed to anticipate death and to realize the liberation body in life. Some Tantric practices are similar and have the similar aims as yoga.

Yoga became popular in the West in the late 1960s and early 1970s and has become a $225 billion industry. In India, however, it is a cultural tradition and remains community activity often led in public parks by gurus who teach breathing exercises, like pranayam, and different 'sun-salutations,' free of charge. [Source: Dean Nelson, The Telegraph, February 23, 2009]

Yoga was inscribed in 2016 on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: “ Yoga consists of a series of poses, meditation, controlled breathing, word chanting and other techniques designed to help individuals build self-realization, ease any suffering they may be experiencing and allow for a state of liberation. It is practised by the young and old without discriminating against gender, class or religion and has also become popular in other parts of the world.” [Source: UNESCO]

Websites and Resources: Yoga Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Yoga: Its Origin, History and Development, Indian government mea.gov.in/in-focus-article ; Different Types of Yoga - Yoga Journal yogajournal.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga Wikipedia ; Medical News Today medicalnewstoday.com ; National Institutes of Health, US government, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction ; Yoga and modern philosophy, Mircea Eliade crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ; India's 10 most renowned yoga gurus rediff.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga philosophy Wikipedia ; Yoga Poses Handbook mymission.lamission.edu ; George Feuerstein, Yoga and Meditation (Dhyana) santosha.com/moksha/meditation

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Book of Yoga: Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Raja Yoga, Jnana Yoga”

by Swami Vivekananda Amazon.com ;

“Gita Wisdom: An Introduction to India's Essential Yoga Text” by Joshua M. Greene Amazon.com ;

“The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West”

by Alistair Shearer Amazon.com ;

“Roots of Yoga” by Sir James Mallinson and Mark Singleton (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice” by Georg Feuerstein and Ken Wilber Amazon.com ;

“The Stories Behind the Poses: The Indian mythology that inspired 50 yoga postures”

by Raj Balkaran Amazon.com ;

“Yoga Mala” by Jois Amazon.com ;

“Light on Yoga: The Bible of Modern Yoga” by B. K. S. Iyengar and Yehudi Menuhin Amazon.com ;

“The Power of Tantra Meditation: 50 Meditations for Energy, Awareness, and Connection”

by Artemis Emily Doyle and Bhairav Thomas Englis Amazon.com ;

“Inner Tantric Yoga: Working with the Universal Shakti: Secrets of Mantras, Deities, and Meditation”

by Dr. David Dr. Frawley (Pandit Vamadeva Shastri) Amazon.com

Definition of Yoga

According to the Indian government: “Yoga is a discipline to improve or develop one’s inherent power in a balanced manner. It offers the means to attain complete self-realization. The literal meaning of the Sanskrit word Yoga is ’Yoke’. Yoga can therefore be defined as a means of uniting the individual spirit with the universal spirit of God. According to Maharishi Patanjali, Yoga is the suppression of modifications of the mind. [Source: ayush.gov.in ***]

“The concepts and practices of Yoga originated in India about several thousand years ago. Its founders were great Saints and Sages. The great Yogis presented rational interpretation of their experiences of Yoga and brought about a practical and scientifically sound method within every one’s reach. Yoga today, is no longer restricted to hermits, saints, and sages; it has entered into our everyday lives and has aroused a worldwide awakening and acceptance in the last few decades. The science of Yoga and its techniques have now been reoriented to suit modern sociological needs and lifestyles. Experts of various branches of medicine including modern medical sciences are realizing the role of these techniques in the prevention and mitigation of diseases and promotion of health. ***

“Yoga is one of the six systems of Vedic philosophy. Maharishi Patanjali, rightly called "The Father of Yoga" compiled and refined various aspects of Yoga systematically in his "Yoga Sutras" (aphorisms). He advocated the eight folds path of Yoga, popularly known as "Ashtanga Yoga" for all-round development of human beings. They are:- Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi. These components advocate certain restraints and observances, physical discipline, breath regulations, restraining the sense organs, contemplation, meditation and samadhi. These steps are believed to have a potential for improvement of physical health by enhancing circulation of oxygenated blood in the body, retraining the sense organs thereby inducing tranquility and serenity of mind. The practice of Yoga prevents psychosomatic disorders and improves an individual’s resistance and ability to endure stressful situations.” ***

David Gordon White, a professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, wrote in his paper “When seeking to define a tradition, it is useful to begin by defining one’s terms. It is here that problems arise. “Yoga” has a wider range of meanings than nearly any other word in the entire Sanskrit lexicon. The act of yoking an animal, as well as the yoke itself, is called yoga. In astronomy, a conjunction of planets or stars, as well as a constellation, is called yoga. When one mixes together various substances, that, too, can be called yoga. The word yoga has also been employed to denote a device, a recipe, a method, a strategy, a charm, an incantation, fraud, a trick, an endeavor, a combination, union, an arrangement, zeal, care, diligence, industriousness, discipline, use, application, contact, a sum total, and the Work of alchemists. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

chakras “So, for example, the ninth-century Netra Tantra, a Hindu scripture from Kashmir, describes what it calls subtle yoga and transcendent yoga. Subtle yoga is nothing more or less than a body of techniques for entering into and taking over other people’s bodies. As for transcendental yoga, this is a process that involves superhuman female predators, called yoginīs, who eat people! By eating people, this text says, the yoginīs consume the sins of the body that would otherwise bind them to suffering rebirth, and so allow for the “union” (yoga) of their purified souls with the supreme god Śiva, a union that is tantamount to salvation. In this ninth-century source, there is no discussion whatsoever of postures or breath control, the prime markers of yoga as we know it today. More troubling still, the third- to fourth-century CE Yoga Sutras and Bhagavad Gita, the two most widely cited textual sources for “classical yoga,” virtually ignore postures and breath control, each devoting a total of fewer than ten verses to these practices. They are far more concerned with the issue of human salvation, realized through the theory and practice of meditation (dhyāna) in the Yoga Sutras and through concentration on the god Krsna in the Bhagavad Gita.

Features of Yoga

Breathing, philosophy and meditation are important aspects of yoga. Practitioners are often told to concentrate on their breathing or meditate on the tip of their nose and learn to direct their body's energy to “chakra centers” and “marma points." Fasting, abstinence from sex, nonviolence and restraint are believed to go hand in hand with the pursuit of higher consciousness. Yoga meditation often features people chanting "om" and reaching towards the sky.

According to the Indian government: “Yoga is universal in character for practice and application irrespective of culture, nationality, race, caste, creed, sex, age and physical condition. Neither by reading the texts nor by wearing the garb of an ascetic, one can become an accomplished Yogi. Without practice, no one can experience the utility of Yogic techniques nor can realize of its inherent potential. Only regular practice (sadhana) creates a pattern in body and mind to uplift them. It requires keen desire on the part of the practitioner to experience the higher states of consciousness through training the mind and refining the gross consciousness. [Source: ayush.gov.in ***]

“Yoga is an evolutionary process in the development of human consciousness. Evolution of total consciousness does not necessarily begin in any particular man rather it begins only if one chooses it to begin. The vices like use of alcohol and drugs, working exhaustively, indulging too much in sex and other stimulation is to seek oblivion, a return to unconsciousness. Indian yogis begin from the point where western psychology end. If Fraud’s psychology is the psychology of disease and Maslow’s psychology is the psychology of the healthy man then Indian psychology is the psychology of enlightenment. In Yoga, it is not a question of psychology of man rather it is a question of higher consciousness. It is not also the question of mental health, rather, it is question of spiritual growth.” ***

Philosophies and Ideas Behind Yoga

Pramana Epistemology, Samkhya Yoga Hindu schools

According to UNESCO: “The philosophy behind the ancient Indian practice of yoga has influenced various aspects of how society in India functions, whether it be in relation to areas such as health and medicine or education and the arts. Based on unifying the mind with the body and soul to allow for greater mental, spiritual and physical wellbeing, the values of yoga form a major part of the community’s ethos.”

The discipline that involves physical positioning of the body (hatha-yoga), which is most commonly equated with yoga outside of India, sees the human body as a series of spiritual centers that can be awakened through meditation and exercise, leading eventually to a oneness with the universe. Tantrism is the belief in the Tantra (from the Sanskrit, context or continuum), a collection of texts that stress the usefulness of rituals, carried out with a strict discipline, as a means for attaining understanding and spiritual awakening. These rituals include chanting powerful mantras; meditating on complicated or auspicious diagrams (mandalas); and, for one school of advanced practitioners, deliberately violating social norms on food, drink, and sexual relations.” [Source: Library of Congress *]

As for the philosophy behind yoga: “The true goal of atman is liberation, or release (moksha ), from the limited world of experience and realization of oneness with God or the cosmos. In order to achieve release, the individual must pursue a kind of discipline (yoga, a "tying," related to the English word yoke) that is appropriate to one's abilities and station in life. For most people, this goal means a course of action that keeps them rather closely tied to the world and its ways, including the enjoyment of love (kama ), the attainment of wealth and power (artha ), and the following of socially acceptable ethical principles (dharma). *

From this perspective, even manuals on sexual love, such as the Kama Sutra (Book of Love), or collections of ideas on politics and governance, such as the Arthashastra (Science of Material Gain), are part of a religious tradition that values action in the world as long as it is performed with understanding, a karma-yoga or selfless discipline of action in which every action is offered as a sacrifice to God. Some people, however, may be interested in breaking the cycle of rebirth in this life or soon thereafter. For them, a wide range of techniques has evolved over the thousands of years that gives Indian religion its great diversity. *

Yoga, Hinduism and Religion

Andrea R. Jain of Indiana University wrote in the Washington Post: “Yoga’s advocates and critics alike perpetuate the myth of its ancient Hindu origins. High-profile conservative pastors have warned of Christians’ inevitable Hinduization should they take up yoga, asserting that “when Christians practice yoga, they must either deny the reality of what yoga represents or fail to see the contradictions between their Christian commitments and their embrace of yoga.” The Hindu American Foundation has made similar arguments, criticizing Americans for failing to acknowledge yoga’s Hindu origins — calling it “one of the greatest gifts of Hinduism to mankind” — and explaining that practitioners subject themselves to Hindu influences, whether intentionally or not. [Source: Andrea R. Jain, Washington Post, August 14, 2015. Jain is an assistant professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and the author of “Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture.”^|^]

chakras and the nervous system“Although there are countless Hindu forms of yoga, the notion that it is originally or definitively Hindu ignores its historical diversity. Throughout its history, yoga was shaped by an array of South Asian practices, ideas and aims widespread among not only Hindus but also Buddhists, Jains and adherents of other religions. Examples include the 3rd-to-4th-century Buddhist yogacara, or “yoga practice” school, and the 6th-century Jain thinker Virahanka Haribhadra and his text, the “Yoga Bindu,” or “seeds of yoga.” ^|^

“Modern postural yoga — that popular fitness regimen made up of sequences of challenging poses — has more varied origins. It is a result of cross-cultural exchanges and influences from modern medicine, sports and exercise programs. In the 1930s, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, for example, became one of the first postural yoga gurus. He was Hindu but taught a form of yoga partly shaped by British calisthenics. Practitioners from India, Europe and the United States, with a wide array of religious convictions or none at all, created the yoga that Americans began adopting widely in the 20th century. ^|^

“In many parts of the world, yoga aficionados tend to avoid describing the practice as religious. Yoga studios, conferences and journals prefer to define it as a regimen for nonsectarian “spiritual growth” or physical “fitness.” But while yoga isn’t specifically Hindu, that doesn’t mean it can’t be religious. Some forms of modern yoga have explicitly religious aims, from Hindu schools such as siddha yoga, which promotes the “strength and delight that come from the certainty of the divine presence within you,” to Christian varieties such as holy yoga, which describes its mission as “experiential worship...to deepen people’s connection to Christ.” Even in other forms, yoga has implicit spiritual dimensions, though they’re not limited to one particular religious tradition. Practitioners participate in scripted rituals requiring movement through a sequence of postures meant to reorient them away from the day’s business and stresses and toward the goal of self-improvement. ^|^

“Yoga classes in secular contexts have qualities that set a religious mood. B.K.S. Iyengar, a significant figure in the creation of modern postural yoga, tied his form of the practice to the ancient “Yoga Sutras of Patanjali,” which emphasize the exalted aim of enlightenment. K. Pattabhi Jois, another 20th-century influencer of modern yoga, taught that the nine positions of the sun salutation sequence delineate from the earliest Hindu texts, the Vedas.” ^|^

Yoga Meditation: Concentration 'On a Single Point'

Mircea Eliade wrote: “The point of departure of Yoga meditation is concentration on a single object; whether this is a physical object (the space between the eyebrows, the tip of the nose, something luminous, etc.), or a thought (a metaphysical truth), or God (Ishvara) makes no difference. This determined- and continuous concentration, called ekagrata ('on a single point'), is obtained by integrating the psychomental flux (sarvarthata, 'variously directed, discontinuous, diffused attention'). This is precisely the definition of yogic technique: yogah cittavritti-nirodhyah, i.e., the yoga is the suppression of psychomental states (Yoga-sutras, 1, 2). [Source:M. Eliade, “Yoga. Immortality and Freedom,” trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: BolIingen Series LVI, 1958), PP. 47-50 +/]

“The immediate result of ekagrata, concentration on a single point, is prompt and lucid censorship of all the distractions and automatisms that dominate -or, properly speaking, compose-profane consciousness. Completely at the mercy of associations (themselves produced by sensations and the vasanas), man passes his days allowing himself to be swept hither and thither by an infinity of disparate moments that are, as it were, external to himself. The senses or the subconscious continually introduce into consciousness objects that dominate and change it, according to their form and intensity. Associations disperse consciousness, passions do it violence, the 'thirst for life' betrays it by projecting it outward. Even in his intellectual efforts, man is passive, for the fate of secular thoughts (controlled not by ekagrata but only by fluctuating moments of concentration, kshiptavikshiptas) is to be thought by objects. Under the appearance of thought, there is really an indefinite and disordered flickering, fed by sensations words, and memory. The first duty of the yogin is to think-that is, not to let himself think. This is why Yoga practice begins with ekagrata, which darns the mental stream and thus constitutes a 'psychic mass,' a solid and unified continuum. +/

“The practice of ekagrata tends to control the two generators of mental fluidity: sense activity (indriya) and the activity of the subconscious (samskara). Control is the ability to intervene, at will and directly, in the functioning of these two sources of mental 'whirlwinds' (cittavritti). A yogin can obtain discontinuity of consciousness at will; in other words, he can, at any time and any place, bring about concentration of his attention on a 'single point' and become insensible to any other sensory or mnemonic stimulus. Through ekagrata one gains a genuine will-that is, the power freely to regulate an important sector of biomental activity. It goes without saying that ekagrata can be obtained only through the practice of numerous exercises and techniques, in which physiology plays a role of primary importance. One cannot obtain ekagrata if, for example, the body is in a tiring or even uncomfortable posture, or if the respiration is disorganized, unrhythmical. This is why, according to Patanjali, yogic technique implies several categories of physiological practices and spiritual exercises (called angas, 'members'), which one must have learned if one seeks to obtain ekagrata and, ultimately, the highest concentration, samadhi. These 'members' of Yoga can be regarded both as forming a group of techniques and as being stages of the mental ascetic itinerary whose end is final liberation. They are: (1) restraints (yama), (2) disciplines (niyama), (3) bodily attitudes and postures (asana); (4) rhythm of respiration (pranayama); (5) emancipation of sensory activity from the domination of exterior objects (pratyahara); (6) concentration (dharana), (7) yogic meditation (dhyana), (8) samadhi (Yoga-sutras, 11, 29). +/

“Each class (anga) of practices and disciplines has a definite purpose. Patanjali hierarchizes these 'members of Yoga' in such a way that the yogin cannot omit any of them, except in certain cases. The first two groups, yama and niyama, obviously constitute the necessary preliminaries for any. type of asceticism, hence there is nothing specifically yogic in them. The restraints (yatna) purify from certain sins that all systems of morality disapprove but that social life tolerates. Now, the moral law can no longer be infringed here-as it is in secular life without immediate danger to the seeker for deliverance. In Yoga, every sin produces its consequences immediately. The five restraints are ahimsa, 'not to kill,' satya, 'not to lie,' asteya, 'not to steal,' brahmacarya, 'sexual abstinence,' aparigraha, 'not to be avaricious.' Together with these restraints, the yogin must practise the niyamas — that is, a series of bodily and psychic 'disciplines.' 'Cleanliness, serenity "samtosha," asceticism "tapas," the study of Yoga metaphysics, and the effort to make God "Ishvara," the motive of all one's actions constitute the disciplines.' (Y.S., II, 32.)” +/

Yogic Postures

easy asana: the mountain pose

Mircea Eliade wrote: “It is only with the third 'member of Yoga' (yoganga) that yogic technique, properly speaking, begins. This third 'member' is asana, a word designating the well-known yogic posture that the Yoga-sutras (11, 46) define as sthirasukham, 'stable and agreeable.' Asana is described in numerous Hatha Yoga treatises; Patanjali defines it only in outline, for asana is learned from a guru and not from descriptions. The important thing is that asana gives the body a stable rigidity, at the same time reducing physical effort to a minimum. Thus, one avoids the irritating feeling of fatigue, of enervation in certain parts of the body, one regulates the physical processes, and so allows the attention to devote itself solely to the fluid part of consciousness. [Source:M. Eliade, “Yoga. Immortality and Freedom,” trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: BolIingen Series LVI, 1958) +/]

“At first an asana is uncomfortable and even unbearable. But after some practice, the effort of maintaining the body in the same position becomes inconsiderable. Now (and this is of the highest importance), effort must disappear, the position of meditation must become natural; only then does it further concentration. 'Posture becomes perfect when the effort to attain it disappears, so that there are no more movements in the body. In the same way, its perfection is achieved when the mind is transformed into infinity-that is, when it makes the idea of its infinity its own content' (Vyasa, ad Y.S. 11, 47.) And Vacaspatimishra, commenting on Vyasa's interpretation, writes: 'He who practices asana must employ an effort that consists in suppressing the natural efforts of the body. Otherwise this kind of ascetic posture cannot be realized.' As for 'the mind transformed into infinity,' this means a complete suspension of attention to the presence of one's own body.+/

“Asana is one of the characteristic techniques of Indian asceticism. It is found in the Upanishads and even in Vedic literature, but allusions to it are more numerous in the Mahabharata and in the Puranas. Naturally, it is in the literature of Hatha Yoga that the asanas play an increasingly important part; the Gheranda Samhita describes thirtytwo varieties of them. Here, for example, is how one assumes one of the easiest and most common of the meditational positions, the padmasana: 'Place the right foot on the left thigh and similarly the left one on the right thigh, also cross the hands behind the back and firmly catch the great toes of the feet so crossed (the right hand on the right great toe and the left hand on the left). Place the chin on the chest and fix the gaze on the tip of the nose.' (II, 8.) Lists and descriptions of asanas are to be found in most of the tantric and Hatha-yogic treatises. The purpose of these meditational positions is always the same, 'absolute cessation of trouble from the pairs of opposites' (Yogasutras, 11, 48.) In this way one realizes a certain 'neutrality' of the senses; consciousness is no longer troubled by the 'presence of the body.' One realizes that first stage towards isolation of consciousness; the bridges that permit communication with sensory activity begin to be raised. +/

“On the plane of the 'body,' asana is an ekagrata, a concentration on a single point; the body is 'tense,' concentrated in a single position. just as ekagrata puts an end to the fluctuation and dispersion of the states of consciousness, so asana puts an end to the mobility and disposability of the body, by reducing the infinity of possible positions to a single archetypal, iconographic posture. Refusal to move (asana), to let oneself be carried along on the rushing stream of states of consciousness (ekagrata) will be continued by a long series of refusals of every kind.” +/

Asanas, Stages and Chakras

more difficult Asana

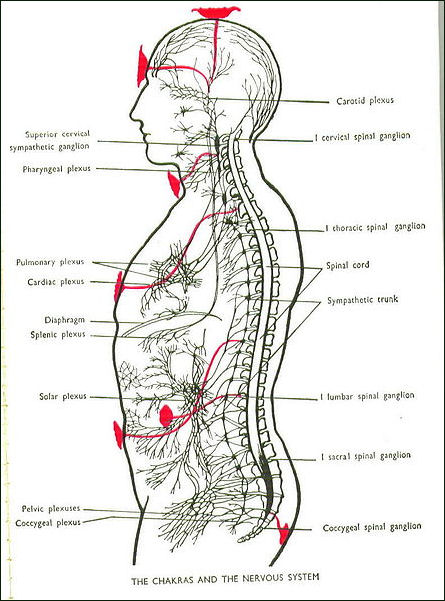

There are 15 basic yoga asanas (positions). They were reportedly developed by Hindus to get warm after taking an early-morning ritualistic bath. They have names like the tree, the dead man, the cobra, the cow face. The plow position in yoga is said to be good for the spine and intestines. The corpse position involves lying on one's back. Breathing techniques ( pranayama ) are also important. Yoga is rooted in the principal; that enlightenment and good health are rooted on the free flow of the life force (prana) and the proper balance between the eight major energy centers (chakras) along channels called Nadi . The lower three chakras serve the body's physical needs. 1) The navel chakra is associated with fire, personal power and storage of the life force. 2) The sacral chakra in the lower abdomen is linked with water and sexual energy. 3) The root chakra in the pelvis corresponds with the earth and lower limbs.

The upper five chakras serve an individual's spiritual needs. They are: 4) the heart chakra associated with air, compassion and love; 5) the throat chakra, linked with ether, self-expression, energy, endurance; 6) the brow chakra, corresponding with the senses, intuition, telepathy, meditation; 7) the crown chakra, associated with intuition and spirituality; and 8) the aura, which surrounds the body and incorporates all the other chakras.

Patanjali, the ancient noble yoga sage, described eight stages of yoga: 1) Yama (universal moral commandments); 2) Niyama (self purication); 3) Asana (posture; 4) Pranayama (breath-control); 5) Pratyahara (withdrawal of mind from extreme objects); 6) Dharana (concentration); 7) Dhyana (meditation); and 8) Samadhi (state of superconciouness).

Yogic Breathing

Breathing is a key element of yoga. If a person is stressed out or anxious their breath is shallow, rapid and uneven. With the meditation the goal is to calm the mind so that breathing is slow, deep and regular. As one focuses one's awareness on breath, the mind becomes absorbed in the rhythm of inhalation and exhalation.

Mircea Eliade wrote: “ The most important-and, certainly, the most specifically yogic of these various refusals is the disciplining of respiration (pranayama) in other words, the 'refusal' to breathe like the majority of mankind, that is, nonrhythmically. Patanjali defines this refusal as follows: 'Pranayama is the arrest [viccheda] of the movements of inhalation and exhalation and it is obtained after asana has been realized. (Y.S., II, 49-) Patanjali speaks of the 'arrest,' the suspension, of respiration; however, pranayama begins with making the respiratory rhythm as slow as possible; and this is its first objective. There are a number of texts that treat of this Indian ascetic technique, but most of them do no more than repeat the traditional formulas. Although pranayama is a specifically yogic exercise, and one of great importance, Patanjali devotes only three sutras to it. He is primarily concerned with the theoretical bases of ascetic practices; technical details are found in the commentaries by Vyasa, Bhoja, and Vacaspatimishra, but especially in the Hatha-yogic treatises. [Source:M. Eliade, “Yoga. Immortality and Freedom,” trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: BolIingen Series LVI, 1958) +/]

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi demonstrating one yogic breathing tecnique

“A remark of Bhoja's reveals the deeper meaning of pranayama: 'All the functions of the organs being preceded by that of respiration there being always a connection between respiration and consciousness in their respective functions-respiration, when all the functions of the organs are suspended, realizes concentration of consciousness on a single object' (ad Y.S. I, 34.). The statement that a connection always exists between respiration and mental states seems to us highly important. It contains far more than mere observation of the bare fact, for example, the respiration of a man in anger is agitated, while that of one who is concentrating (even if only provisionally and without any yogic purpose) becomes rhythmical and automatically slows down, etc.+/

“The relation connecting the rhythm of respiration with the states of consciousness mentioned by Bhoja, which has undoubtedly been observed and experienced by yogins from the earliest times-this relation has served them as an instrument for 'unifying' consciousness. The 'unification' here under consideration must be understood in the sense that, by making his- respiration rhythmical and progressively slower, the yogin can 'penetrate'-that is, he can experience, in perfect lucidity- certain states of consciousness that are inaccessible in a waking condition, particularly the states of consciousness that are peculiar to sleep. For there is no doubt that the respiratory system of a man asleep is slower than that of a man awake. By reaching this rhythm of sleep through the practice of pranayama, the yogin, without renouncing his lucidity, penetrates the states of consciousness that accompany sleep.” +/

Four Modalites of Consciousness

Mircea Eliade wrote: “The Indian ascetics recognize four modalites of consciousness (beside the ecstatic 'state')- diurnal consciousness, consciousness in sleep with dreams, consciousness in sleep without dreams, and 'cataleptic consciousness.' By means of pranayama-that is, by increasingly prolonging inhalation and exhalation (the goal of this practice being to allow as long an interval as possible to pass between the two moments of respiration-the yogin can, then, penetrate all the modalities of consciousness. For the noninitiate, there is discontinuity between these several modalities; thus he passes from the state of waking to the state of sleep unconsciously. The yogin must preserve continuity of consciousness-that is, he must penetrate each of these states with' determination and lucidity. [Source:M. Eliade, “Yoga. Immortality and Freedom,” trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: BolIingen Series LVI, 1958) +/]

“But experience of the four modalities of consciousness (to which a particular respiratory rhythm naturally corresponds), together with unification of consciousness (resulting from the yogin's getting rid of the discontinuity between these four modalities), can only be realized after long practice. The immediate goal of pranayama is more modest. Through it one first of all acquires a 'continuous consciousness,' which alone can make yogic meditation possible. The respiration of the ordinary man is generally arrhythmic; it varies in accordance with external circumstances or with mental tension. This irregularity produces a dangerous psychic fluidity, with consequent instability and diffusion of attention. One can become attentive by making an effort to do so. But, for Yoga, effort is an exteriorization. Respiration must be made rhythmical, if not in such a way that it can be 'forgotten' entirely, at least in such a way that it no longer troubles us by discontinuity. Hence, through pranayama, one attempts to do away with the effort of respiration, rhythmic breathing must become something so automatic that the yogin can forget it. +/

“Rhythmic respiration is obtained by harmonizing the three 'moments'; inhalation (paraka), exhalation (recaka), and retention of the inhaled air (kumbhaka). These three moments must each fill an equal space of time. Through practice the yogin becomes able to prolong them considerably, for the goal of pranayama is, as Patanjali says, to suspend respiration as long as possible; one arrives at this by progressively retarding the rhythm.” +/

Samadhi

Mircea Eliade wrote: “ The passage from 'concentration' to 'meditation' does not require the application of any new technique. Similarly, no supplementary yogic exercise is needed to realize samadhi, once the yogin has succeeded in 'concentrating' and 'meditating.' Samadhi, yogic 'enstasis,'. is the final result of the crown of all the ascetic's spiritual efforts and exercises. The meanings of the term Samadhi are union, totality; absorption in, complete concentration of mind; conjunction. The usual translation is 'concentration,' but this embarks the risk of confusion with dharana. Hence we have preferred to translate it 'entasis,' 'stasis,' and conjunction. [Source: M. Eliade, “Yoga. Immortality and Freedom,” trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: BolIingen Series LVI, 1958) +/]

“Patanjali and his commentators distinguish several kinds or stages of supreme concentration. When Samadhi is obtained with the help of an object or idea (that is, by fixing one's thought on a point in space or on an idea), the stasis is called samprajnata samadhi ('enstasis with support,' or 'differentiated enstasis'). When, on the other hand, samadhi is obtained apart from any 'relation' (whether external or mental) that is, when one obtains a 'conjunction' into which no otherness' enters, but which is simply a full comprehension of being one has realized asamprajnata-samadhi ('undifferentiated stasis'). Vijnanabhikshu adds that samprajnata samadhi is a means of liberation in so far as it makes possible the comprehension of truth and ends every kind of suffering. But asamprajnata samadhi destroys the 'impressions [samskara] of all antecedent mental functions' and even succeeds in arresting the karmic forces already set in motion by the yogin's past activity. During 'differentiated stasis,' Vijnanabhikshu continues, all the mental functions are 'arrested' ('inhibited'), except that which 'meditates on the object'; whereas in asampranata samadhi all 'consciousness' vanishes, the entire series of mental functions are blocked. 'During this stasis, there is no other trace of the mind [citta] save the impressions [samskara] left behind (by its past functioning). If these impressions were not present, there would be no possibility of returning to consciousness.'+/

“We are, then, confronted with two sharply differentiated classes of states.' The first class is acquired through the yogic technique of concentration (dharana) and meditation (dhyana), the second class comprises only a single 'state'-that is, unprovoked enstasis, 'raptus.' No doubt, even this asamprajnata samadhi is always owing to prolonged efforts on the yogin's part. It is not a gift or a state of grace. One can hardly reach it before having sufficiently experienced the kinds of Samadhi included in the first class. It is the crown of the innumerable 'concentrations' and 'meditations' that have preceded it. But it comes without being summoned, without being provoked, without special preparation for it. That is why it can be called a 'raptus.' +/

“Obviously, 'differentiated enstasis,' samprajnata-samadhi, comprises several stages. This is because it is perfectible and does not realize an absolute and irreducible 'state.' Four stages or kinds are generally distinguished: 'argumentative' (savitarka), 'nonargumentative' (nirvitarka), reflective' (savicara), 'super-reflective' (nirvicara). Patanjali also employs another set of terms: vitarka, vicara, ananda, asmita. (Y-S-, I, 17). But, as Vijnanabhikshu, who reproduces this list, remarks, 'the four terms are purely technical, they are applied conventionally to different forms of realization.' These four forms or stages of samprajnata samadhi, he continues, represent an ascent; in certain cases the grace of God (ishvara) permits direct attainment of the higher states, and in such cases the yogin need not go back and realize the preliminary states. But when this divine grace does not intervene, he must realize the four states gradually, always adhering to the same object of meditation (for example, Vishnu). These four grades or stages are also known as samapattis, 'coalescences.' (Y.S., I, 41-) +/

“All these four stages of samprajnata samadhi are called bija samadhi ('samadhi with seed') or salambana samadhi ('with support):, for Vijnanabhikshu tells us, they are in relation with a 'substratum' (support) and produce tendencies that are like 'seeds' for the future functions of consciousness. Asamprajnata samadhi, on the contrary, is nirbija, 'without seed,' without support. By realizing the four stages of samprajnata, one obtains the 'faculty of absolute knowledge' (Y.S., 1, 48) This is already an opening towards samadhi 'without seed,' for absolute knowledge discovers the ontological completeness in which being and knowing are no longer separated. Fixed in samadhi, consciousness (citta) can now have direct revelation of the Self (purusha). Through the fact that this contemplation (which is actually a 'participation') is realized, the pain of existence is abolished. +/

“Vyasa (ad Y.S., III, 55) summarizes the passage from samprajnata to asamprajnata samadhi as follows: through the illumination (prajna, 'wisdom') spontaneously obtained when he reaches the stage of dharma-megha-samadhi, the yogin realizes 'absolute isolation' (kaivalya)-that is, liberation of purusha from the dominance of prakriti. For his part, Vacaspatimishra says that the 'fruit' of samprajnata samadhi is asamprajnata samadhi, and the 'fruit' of the latter is kaivalya, liberation. It would be wrong to regard this mode of being of the Spirit as a simple 'trance" in which consciousness was emptied of all content. Nondifferentiated enstasis is not absolute emptiness.' The 'state' and the 'knowledge' simultaneously expressed by this term refer to a total absence of objects in consciousness, not to a consciousness absolutely empty. For, on the contrary, at such a moment consciousness is saturated with a direct and total intuition of being. As Madhava says, 'nirodha [final arrest of all psychomental experience] must not be imagined as a nonexistence, but rather as the support of a particular condition of the Spirit.' It is the enstasis of total emptiness, without sensory content or intellectual structure, an unconditioned state that is no longer 'experience' (for there is no further relation between consciousness and the world) but 'revelation.' Intellect (buddhi), having accomplished its mission, withdraws, detaching itself from the Self (purusha) and returning into prakriti. The Self remains free, autonomous: it contemplates itself. 'Human' consciousness is suppressed; that is, it no longer functions, its constituent elements being reabsorbed into the primordial substance. The yogin attains deliverance; like a dead man, he has no more relation with life; he is 'dead in life.' He is the jivan-mukta, the 'liberated in life.' He no longer lives in time and under the domination of time, but in an eternal present, in the nunc stans by which Boethius defined eternity.” +/

Importance of Gugus in Yoga

Babamani According to UNESCO: “Traditionally, yoga was transmitted using the Guru-Shishya model (master-pupil) with yoga gurus as the main custodians of associated knowledge and skills. Nowadays, yoga ashrams or hermitages provide enthusiasts with additional opportunities to learn about the traditional practice, as well as schools, universities, community centres and social media. Ancient manuscripts and scriptures are also used in the teaching and practice of yoga, and a vast range of modern literature on the subject available.” [Source: UNESCO]

A central aspect of all religious discipline in India, regardless of its emphasis, is the importance of the guru, or teacher. Indian religion may accept the sacredness of specific texts and rituals but stresses interpretation by a living practitioner who has personal experience of liberation and can pass down successful techniques to devoted followers. In fact, since Vedic times, it has never been possible, and has rarely been desired, to unite all people in India under one concept of orthodoxy with a single authority that could be presented to everyone. Instead, there has been a tendency to accept religious innovation and diversity as the natural result of personal experience by successive generations of gurus, who have tailored their messages to particular times, places, and peoples, and then passed down their knowledge to lines of disciples and social groups. As a result, Indian religion is a mass of ancient and modern traditions, some always preserved and some constantly changing, and the individual is relatively free to stress in his or her life the beliefs and religious behaviors that seem most effective on the path to deliverance. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to the Indian government: All paths of Yoga (Japa, Karma, Bhakti etc.) have healing potential to shelter out the effects of pains. However, one especially needs proper guidance from an accomplished exponent, who has already treaded the same track to reach the ultimate goal. The particular path is to be chosen very cautiously in view of his aptitude either with the help of a competent counselor or consulting an accomplished Yogi. [Source: ayush.gov.in]

Describing a class by the 84-year-old Sri K. Pattabhi Jois in Mysore, Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker, “Jois doesn't teach in the manner of a Western aerobics class, by standing in the front of the room and yelling instructions. Instead each student shows up at an appointed time and works through the series of postures at his or her own place, while Jois, barrel-stomached in black Calvin Klein briefs and, and bare-chested except for his Brahmin stings performs what are known in the yoga business as adjustments — winching a leg into place or leaning heavily on a student's back to stretch him or her further."

“All the men are stripped to the waist, the women are in spandex, and all of them are slick with sweat as they twist their bodies in unimaginable knots or deep into breathtaking backbends, seeming to hang suspended in the air they jump from one position to the next...The room is silent but for the subtle chorus of long, repetitive, nasal hisses, and occasional pigeon English command from Jois, who barks, “Nooooo! You go down!...It is a serenity born of concentration and pain — torture meets bliss."

Health Benefits of Yoga

Tridandiswamiji One of the primary aims of yoga is to improve mental and physical health by keeping the body clean and flexible. The postures are said to help harmonize mental energy flow by removing blockages. Correct breathing helps create calmness, mental equilibrium and focus energy. Practitioners of yoga are taught to breath using both their abdomen and thorax to maximum lung capacity, which helps release tensions, bring relaxation and increase oxygen to the brain.

There have not been many Western medical studies on the effects of yoga but the ones that have been done have shown that yoga can help relieve everything from carpal tunnel syndrome to post-menopausal hot flashes to fat-clogged arteries. Breath exercise have been shown to relieve blood pressure and stress hormones. Stretching improves the drainage of the lymphatic vessels (the body's waste disposal system). Holding the positions helps build muscle tone and strengthens joints

Breathing is a key element of yoga. If a person is stressed out or anxious their breath is shallow, rapid and uneven. With the meditation the goal is to calm the mind so that breathing is slow, deep and regular. As one focuses one's awareness on breath, the mind becomes absorbed in the rhythm of inhalation and exhalation.

Yoga, the basic construct of meditation is said to have a number of beneficial effects so long as physical and mental wellbeing is concerned. In Patanjali, the ancient Indian scripture on medical science references are found of Yoga’s disease healing capacities. These biological benefits of yoga are being increasingly recognized by the global medical fraternity. [Source:differencebetween.net]

Health benefits of yoga include: 1) increased flexibility; 2) increased muscle tone and strength; 3) improved circulatory and cardio health; 4) helps you sleep better; 5) increased energy levels; 6) improved athletic performance; 7) reduced injuries; 8) detoxifies your organs; 9) improved posture; 10 ) reduces anxiety and depression; 11) helps with chronic pain; and 12 ) releases endorphins that improve your mood. [Source: doyogawithme.com]

According to the Malaysian Star; 1) Increased flexibility: Yoga consists of a series of poses that require stretching. After a few sessions, people will notice that they can stretch farther and that movement in daily life is much easier, more fluid and they are less stiff. 2) Detoxification: Aids in detoxification of the body as many of the poses stimulate blood flow to the different organs, flushing out toxins. It also emphasises breathing techniques which increase oxygenation of the body. Some of the poses also stimulate the digestive tract, improving digestion. 3) Weight reduction: Helps people be more aware of their bodies and eat healthy. Many of the asana stimulate glands, such as the thyroid gland, which can help increase metabolism. 4) Toning muscles: Strengthens muscles, including those not used on a daily basis, adding to overall tone and strength. 5) Self-awareness: Helps make people be aware of their bodies and moods, but more importantly, gives them tools to help address problems. For instance, people experiencing pain can find poses that target and relieve the pain. 6) Stress reduction and relaxation: Teaches people to focus on themselves and their breathing. Gives them a sense of control over situations and let go of those things that cannot be controlled. Improves quality of sleep. While yoga has benefits for many people, those with high blood pressure; risk of blood clots; eye conditions, including glaucoma; and osteoporosis should consult their physician. [Source: The Star, December 5, 2008]

Andrea R. Jain of Indiana University wrote in the Washington Post, “When we think of yoga today, we envision spandex-clad, perspiring, toned bodies in a room filled with mats. More than half of yoga enthusiasts in the United States say physical fitness is their primary motivation, according to a Yoga Journal survey, and 78 percent say they’re in it mostly to gain flexibility. That vision is a modern invention; nothing like it has existed in most of yoga’s history. [Source: Andrea R. Jain, Washington Post, August 14, 2015]

Yoga Makes UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List

Guruji GolwalkarIn 2016, yoga was inscribed in 2016 on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. AFP reported: “Yoga, the mind-body discipline based on ancient Indian philosophy and now practised all over the world, has joined Unesco’s list of intangible world heritage. It was added to the prestigious list in recognition of its influence on Indian society, from health and medicine to education and the arts, the world heritage committee said in a statement. “Designed to help individuals build self-realisation, ease any suffering they may be experiencing and allow for a state of liberation, [yoga] is practised by the young and old without discriminating against gender, class or religion,” Unesco added in a tweet. [Source: Agence France-Presse, 1 December 2016]

“The list of intangible cultural treasures was created in 2006, mainly to increase awareness about them, while Unesco also sometimes offers financial or technical support to countries struggling to protect them. The Paris-based UN body also added Cuba’s rumba dance and Belgium’s beer culture to the list, which also includes the Mediterranean diet, Peking opera and the Peruvian scissors dance.

Yoga as a Fashion

In the old days, teaching yoga was something that people did because they loved yoga and the basic, simplified lifestyle that went with it. Now there is a lot of money in it. By some estimates 20 million American practice yoga regularly. Many Indian yuppies and middle class families participate in pilgrimages and take yoga classes to explore their spiritual roots.

Swami Saraswatiji Yoga became very popular in the United States and Europe in the early 2000s. Health clubs and corporate retreats began offering it. Trendy television characters such as those in Sex and the City did it. Vacations centered around it were offered in Turkey, Spain, Hawaii and Peru. Companies marketed sexy “chakra” tank tops, disco yoga and yoga gold classes. Television commercials featured people doing yoga in front of SUVs and yoga classes that promised to lift breasts and increase success in business. . Purists found all this to be a real turn off.

Among the celebrities that swear by yoga are Jude Law, Angelina Jolie, Ricky Martin, Kate Moss, Sting, Meg Ryan, Stephen Spielberg, Dennis Quaid, Woody Harrelson, Gwentyth Paltrow, Christy Turlington. Kareem Abdul Jabaar, Julia Roberts, Shirley MacLaine, Raquel Welch, Uma Thurman, Penelope Cruz, John Cusack, the Beastie Boys, Sean Connery, Barbara Walters, and Marisa Tomei.

Courtney Love, Madonna, Cindy Crawford, David Duchovny and Rosana Arquette are into Kundalini yoga. Candice Bergen, Rachel Weisz, Ashley Judd, and Brooke Shields like Bikam yoga. For a while former United States Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Conner took regular classes.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018