JAINISM

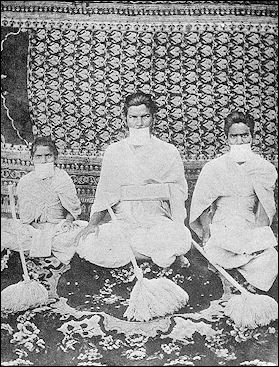

Jain monks Jainism is one the world's oldest religions. It is the oldest continuous monastic tradition in India and possibly the oldest ascetic religious tradition on Earth. Jainism refers to the path of the Jinas, or victors. This tradition is traced to Var-dhamana Mahavira (The Great Hero; ca. 599-527 B.C.), the twenty-fourth and last of the Tirthankaras (Sanskrit for fordmakers). Jainism is an offshoot of Hinduism and has many similarities with Buddhism but is regarded as more rigid and ascetic. Its founder Mahavira was a 6th century B.C. ascetic. Te religion emphasizes meditation, the sanctity of life and non-violence and maintains there is a basic life principal in all objects. Its adherents aim to attain identity through ascetic practices and even self mutilation.” The basic tenets of Jainism this religion influenced Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

Jainism, like Buddhism, originated in India in the sixth century B.C. Jainism and Hinduism share many social practices (several castes have both Hindu and Jain members) and many Hindus consider Jainism to be a branch of Hinduism. Jainism revolves around Jinas — Buddha-like human teachers who have attained “moksha” (enlightenment) and share their knowledge with followers. These teachers are also known as “tirthankaras” (“builders of the ford”), a reference to their efforts to lead souls across the river of rebirth.

Vinay Lal wrote: “Jainism is atheistic in nature as the existence of God is irrelevant to its doctrine. The Jains postulate the existence of a soul for everything, including non-living things. The vow of non-violence, or ahimsa, was of paramount importance to the Jaina, since even the unconscious killing of an insect while walking or breathing was a sin. (Orthodox Jain monks can still be observed wearing a net over their mouth, and they gently sweep the street as they walk to remove insects from their path, lest they should inadvertently crush them.) The purification of the soul was conceived as the purpose of living. Contrary to what the Upanishads or Hindu philosophical texts suggests, Jains were inclinced to believe that this purification could not be attained by knowledge, but only through living a balanced life. [Source:Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

Websites and Resources on Jainism: Jainism Resources cs.colostate.edu ; religious Tolerance Page religioustolerance.org/jainism ; Learn Jainism Images learnjainism.org/cid ; Jain Religion jainreligion.in ; Official Jain website djms.in/resident/djms_idx ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jains” by Paul Dundas Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Jain Philosophy” by Parveen Jain , Cogen Bohanec, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Jainism: An Introduction (I.B.Tauris Introductions to Religion) Amazon.com

Jains

Jainism is followed by about 4.5 million people. Nearly all of them are in India, particularly in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka. Outside India, some of the largest Jain communities can be found in Canada, Europe, and the United States. Japan is also home to a fast-growing community of converts. There are about 50,000 Jains and 50 Jain temples in the United States.

In keeping with their commitment to non-violence, Jains are strict vegetarians. Wheat, rice, lentils or pulses, beans, and oilseeds are considered harmless foods, as are fruits and vegetables that ripen on plants or fall from the branches of trees. Respect for all life is a major tenet of Jainism, and enterprises that improve the quality of life-such as hospitals, schools, and animal care facilities-are funded by the Jain community throughout India. [Source: Leona Anderson, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Some forms of employment seem to be incompatible with Jainism — Jains can't work as butchers, fishermen, brewers, wine-merchants, arms-dealers, mill-owners and so on. Lay Jains should be vegetarians: as their scripture forbids them to intentionally injure any form of life above the class of one-sensed beings, they can only eat vegetables. Nor will Jains serve meat to guests, or permit any ill-treatment of animals.

Jain Monks, Nuns and Lay People

Jains make a distinction between 1) monks and nuns; and 2) lay people: According to the BBC: “Monks and nuns follow the doctrine of ahimsa in every part of their life with great strictness: 1) monks walk in the street and sweep the ground with the utmost care so as to avoid accidentally crushing crawling insects; 2) monks wear muslin cloths over their mouths to make sure they don't swallow and thus harm any flies; and 3) monks are not allowed to use violence in self-defence even if this results in their own death

Lay Jains try to follow the doctrine in every part of their life, but not so strictly — since full ahimsa is not compatible with everyday life. Some harm is inevitably done, for instance, in the following activities: 1) preparing food’ 2) ) cleaning buildings; 3) walking; 4) driving and 5) self-defence against attack The golden rule for lay Jains is to avoid doing any harm intentionally; harm which is unavoidably done in the course of employment, normal domestic life, or in self-defence is accepted, although should be avoided if possible.

Jains with a strong devotion to ahimsa are often the ones ordained as monks and nuns. Some live the life of wandering ascetics. Most Jains today, however, are lay, living secular lives but trying to adhere to the principle of ahimsa in as many ways as possible. The laity support the wandering ascetics by providing food and shelter; the ascetics, in turn, provide religious and moral guidance. [Source: Marcus Banks, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992]

Early History of Jainism

Joganis Jainism is regarded as the oldest ascetic religious tradition in the world. Like Buddhism it traces its origins back to the Sramana movements in modern-day Bihar and Nepal in the 6th century B.C. and has been continuously practiced since then. The other Sramana movements, including Buddhism, died out. [Source: Marcus Banks, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992 |~|]

Jainism was initially a Brahmin school that emerged around the same time as Buddhism. Buddhism and Jainism had a profound impact on Indian and Hindu culture. They discouraged caste distinctions, abolished hereditary priesthoods, made poverty a precondition of spirituality and advocated the communion with the spiritual essence of the universe through contemplation and meditation.

The Sramana schools, including Jainism, reacted against the contemporary form of Hinduism (known as Brahmanism). They posited that worldly life is inherently unhappy — an endless cycle of death and rebirth — and that liberation from it is achieved not through sacrifice or appeasing the gods, but through inner meditation and discipline. Thus, while Jains in India today share many social practices with their Hindu neighbors their religious tradition is in many ways philosophically closer to Buddhism, though distinctly more rigid in its asceticism than Buddhism. |~|

The origins of Jainism have been traced to Palanpur, a small town in Western India. It was reportedly founded about 30 years before Buddhism as as attempt to reform the less appealing aspects of Hinduism, namely the caste system. The Jain memorial mound in at Mathur is believed to be the oldest structure in India. There are old Jain temples in Kaligamalai, Ahmedabad, Ellora, Ajmere and Mount Abu.

Vinay Lal wrote: The changes in economic life during the seventh century BC, such as the growth of towns and the rapid development of trade, were linked to religious and philosophical speculation. The conflict between the established Hindu orthodoxy and the aspirations of the newly emergent groups in the towns gave rise to various heterodoxies, from determinism to materialism. However, only two of these 'sects' were to endure, namely Buddhism and Jainism. [Source:Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

“Jaina ideas can be traced back to the seventh century, though it was Mahavira who formalized the philosophy of what was to be known as Jainism in the sixth century. Mahavira, most likely born around 540 BC, was a Kshatriya of high Licchavi tribal birth. At the age of 30, he renounced family life and proceed to live, for the next 12 years, as an ascetic. He abandoned even clothes to go naked. ==

See Separate Article: ANCIENT INDIA IN THE TIME OF THE BUDDHA factsanddetails.com

Mahavira, Founder of Jainism

Vardhamana Mahavira (599 and 527 B.C.) is the founder of Jainism and the prophet and prince of the Jains. He is mentioned in Buddhist scripture as the “Naked Ascetic” and was a contemporary of Confucius in China and Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Isaiah in Israel and Aristotle and Plato in Greece. Like Buddha he forsook his life of wealth and privilege for a spiritual life, and rejected the sacrificial rites of the Hindus and the caste system. Vardhaman. Mahavira means “great hero.”

According to legend, Mahavira was born to a ruling family in the town of Vaishali, located in the modern state of Bihar. At the age of thirty, he renounced his wealthy life and devoted himself to fasting and self-mortification in order to purify his consciousness and discover the meaning of existence. He never again dwelt in a house, owned property, or wore clothing of any sort. Following the example of the teacher Parshvanatha (ninth century B.C.), he attained enlightenment and spent the rest of his life meditating and teaching a dedicated group of disciples who formed a monastic order following rules he laid down. His life's work complete, he entered a final fast and deliberately died of starvation”[Source: Library of Congress]

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Mahavira, the founder of Jainism, and Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, both lived in the sixth century B.C., and both were princes who left their fathers’ kingdoms for the life of an ascetic. They shared the belief in karma and samsara, and sought release (moksha) through meditation and control of one’s desires. Unlike Buddhism, however, Jainism never spread beyond India. Today there are some two million Jains in western India, where Mahavira taught. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

“As a prince, Mahavira’s name was Vardhamana. The ideal Aryan prince was a vira, meaning “brave warrior.” Vardhamana also wished to be known as a brave warrior, not in a battle against human foes but in his battle against his own desires. So he took the name Mahavira (maha = great). A person who has absolute control over his senses and has become a great teacher is known as a jina or tirthankara. Mahavira’s followers believed that he was the last of twenty-four tirthankaras.”

Life of Mahavira

Mahavira was born on the Ganges into a princely family that belonged to the “Kshatriya” warrior caste. It is said that he lived in heaven before he was placed into his mother's womb after she had 14 prophetic dreams. While he was in his mother’s womb Mahavira ascribed to the doctrine of non-violence and never kicked inside his mother, not even once.

Mahavira married the daughter of another prince. At age 30, after his wife gave birth to a daughter he became an ascetic. According to legend, he tore out all of his hair in five handfuls and gave away all his possessions including his clothes and then wandered the countryside naked. He inflicted a number of tortures on himself in attempt to gain mastery over his body and soul.

Mahavira went about naked for 12 years and attempted to reach of state of “jina” . During the 13th year of his ascetic period , after a long fast he achieved his goal and achieved a "unobstructed, unimpeded, infinite knowledge called “kevala” while sitting underneath a sala tree. The story is similar to the story of Buddha’s enlightenment.

Mahavira then put on some clothes and devoted the rest of his life to teaching others how to experience what he did. Mahavira told his followers that they should not worship any person or object but should live "a life quiet and unperturbed, self denying, harmless and prayerless." He converted 12 disciples who structured his teaching into the Jain scriptures and expanded the community of followers. Mahavira died while meditating. After his death miracles grew up about his divine powers and people worshiped him and idolized images of him.

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: Mahavira led an austere life, teaching, meditating, begging for food, and denying his body any comforts. When his clothes fell into tatters, he went without them, “sky-clad” for the rest of his life. Jain monks disagreed about how far their austerities should go. One group held that, like Mahavira, they should teach “sky-clad,” or naked. Those opposed wore white robes. Most present-day Jain monks are “white-clad.” Mahavira taught his followers to detach themselves from worldly desires and also from their own viewpoints. He suggested that it is often easier to give up material possessions than it is to part with one’s opinions. According to Mahavira, a person can see only a very small part of the truth, and what one believes to be true depends on many factors like social status, education, and context. An ancient Jain parable interpreted by a nineteenth-century poet [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

It was six men of Indostan To learning much inclined

Who went to see the Elephant (Though all of them were blind)

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The first approached the Elephant And happened to fall Against his broad and sturdy side At once began to bawl: “Bless me! But the elephant Is very like a wall.” The second, feeling of the tusk Cried, “Ho! What have we here, So very round and smooth and sharp? To me ’tis mighty clear This wonder of an Elephant Is very like a spear.” The third approached the animal, And happened to take The squirming trunk within his hands, Thus boldly up and spake: “I see,” quoth he; “the Elephant Is very like a snake.” The fourth reached out his eager h and And felt about the knee.

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” quoth he;

“’Tis clear enough the elephant is very like a tree.”

The fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said “E’en the blindest man Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan.”

The sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope

Than seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” quoth he, “the elephant

Is very like a rope.”

And so these men of Indostan Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong.

Translated by John Godfrey Saxe (American, 1816–1887)

Jain Nonviolence: the Example of Mahavira

Vardhamarma Mahavira ('The Great Hero') was a contemporary of the Buddha. He is said to have left his home at the age of thirty and wandered for twelve years in search of salvation. At the age of fortytwo he obtained enlightenment and became a 'conqueror' (jina, term from which the Jain took their name). Mahavira founded an order of naked monks and taught his doctrine of salvation for some thirty years. He died in 468 B.C., at the age of seventy-two, in a village near Patna.

'Akaranga-sutra, I, 8, 1-3-IV-8 reads:

1. 3. For a year and a month he did not leave off his robe. Since that time the Venerable One, giving up his robe, was a naked, world relinquishing, houseless (sage).

4. Then he meditated (walking) with his eye fixed on a square space before him of the length of a man. Many people assembled, shocked at the sight; they struck him and cried.

5. Knowing (and renouncing) the female sex in mixed gathering places, he meditated, finding his way himself: I do not lead a worldly life.

6. Giving up the company of all householders whomsoever, he meditated. Asked, he gave no answer; he went and did not transgress the right path.

7. For some it is not easy (to do what he did), not to answer those who salute; he was beaten with sticks, and struck by sinful people. . . .

10. For more than a couple of years he led a religious life without using cold water; he realize.1 singleness, guarded his body, had got intuition, and was calm.

11. Thoroughly knowing the earth-bodies and water-bodies and firebodies and wind-bodies, the lichens, seeds, and sprouts,

12. He comprehended that they are, if narrowly inspected, imbued with life, and avoided to injure them; he, the Great Hero.

13. The immovable (beings) are changed to movable ones, and the movable beings to immovable ones; beings which are born in all states become individually sinners by their actions.

14. The Venerable One understands thus: he who is under the conditions (of existence), that fool suffers pain. Thoroughly knowing (karman), the Venerable One avoids sin.

15. The sage, perceiving the double (karman), proclaims the incomparable activity, he, knowing one; knowing the current of worldliness, the current of sinfulness, and the impulse.

16. Practicing the sinless abstinence from killing, be did no acts, neither himself nor with the assistance of others; be to whom women were known as the causes of all sinful acts, he saw (the true sate of the world). . . .

III. 7. Ceasing to use the stick (i.e. cruelty) against living beings, abandoning the care of the body, the houseless (Mahavira), the Venerable One, endures the thorns of the villages (i.e. the abusive language of the peasants), (being) perfectly enlightened.

8. As an elephant at the head of the battle, so was Mahavira there victorious. Sometimes he did not reach a village there in Ladha.

9. When he who is free from desires approached the village, the inhabitants met him on the outside, and attacked him, saying, 'Get away from here.'

10. He was struck with a stick, the fist, a lance, hit with a fruit, a clod, a potsherd. Beating him again and again, many cried.

11. When he once (sat) without moving his body, they cut his flesh, tore his hair under pains, or covered him with dust.

12. Throwing him up, they let him fall, or disturbed him in his religious postures; abandoning the care of his body, the Venerable One humbled himself and bore pain, free from desire.

13. As a hero at the head of the battle is surrounded on all sides, so was there Mahavira. Bearing all hardships, the Venerable One, undisturbed, proceeded (on the road to Nirvana). . . .

VI 1. The Venerable One was able to abstain from indulgence of the flesh, though never attacked by diseases. Whether wounded or not wounded, he desired not medical treatment.

2. Purgatives and emetics, anointing of the body and bathing, shampooing and cleaning of the teeth do not behoove him, after he learned (that the body is something unclean).

3. Being averse from the impressions of the senses, the Brahmana wandered about, speaking but little. Sometimes in the cold season the Venerable One was meditating in the shade.

4. In summer he exposes himself to the heat, he sits squatting in the sun; he lives on rough (food); rice, pounded jujube, and beans.

5. Using these three, the Venerable One sustained himself eight months. Sometimes the Venerable One did not drink for half a month or even for a month.

6. Or he did not drink for more than two months, or even six months, day and night, without desire (for drink). Sometimes he ate stale food.

7. Sometimes he ate only the sixth meal, or the eighth, the tenth, the twelfth; without desires, persevering in meditation.

8. Having wisdom, Mahavira committed no sin himself, nor did he induce other to do so, nor did he consent to the sins of others.

[Source: Eliade Page website, Translation from Prakrit by Herman Jacobi, Jaina Sutra, part 1, in Sacred Books of the East, (Oxford, 1884), PP. 85-7

Twenty Four Holymen

There is evidence that Jain practices existed before Mahavira. The Jain texts refer to a succession of prophets (“tirthankaras” ) that stretched back to the mythological past. Mahavira was the 24th and last of these) prophets. The tirthankkaras liberated their souls through meditation and ascetic practices and preached a message of salvation before leaving their mortal bodies.

The 24 tirthankaras are regarded as holy men who acted as intermediaries between mankind and heaven. They are objects of great reverence. Jains honor them not so much to win favors on earth and rewards in the afterlife but rather to honor what they achieved and use their stories as model’s for one’s own behavior.

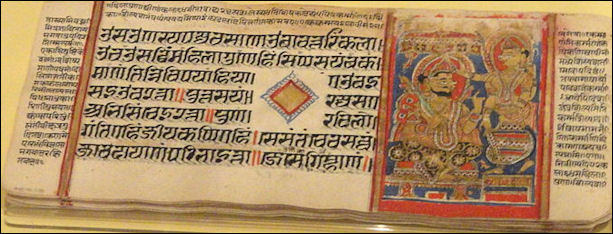

Kalpasutra (legends of the Jain saviors), late 15th century

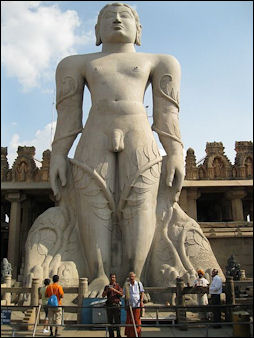

Jain temples are always dedicated to one of the tirthankaras, usually Rsabha and Nemi, the first two, and Parsva and Mahavira , the last two. Pasva may have been a historical figure that lived in Varanasi the 9th century B.C. Gomateshwara is a Jain saint that meditated in one place for so long, creepers grew up his legs and body.

Later History of Jainism

Both Jainism and Buddhism "outlawed caste distinctions, abolished hereditary priesthood, made poverty a precondition of spirituality and advocated the communion with the spiritual essence of the universe through contemplation and meditation.” Both Jainism and Buddhism posited that existence was basically an unhappy cycle of death and rebirth and the goal of both religions was to break free from this cycle through meditation and discipline. They also both rejected the Hindu customs of sacrifice and appeasement of the gods.

By the first century A.D., the Jain community evolved into two main divisions based on monastic discipline: the Digambara or "sky-clad" monks who wear no clothes, own nothing, and collect donated food in their hands; and the Svetambara or "white-clad" monks and nuns who wear white robes and carry bowls for donated food. The Digambara do not accept the possibility of women achieving liberation, while the Svetambara do. Western and southern India have been Jain strongholds for many centuries; laypersons have typically formed minority communities concentrated primarily in urban areas and in mercantile occupations. In the mid-1990s, there were about 7 million Jains, the majority of whom live in the states of Maharashtra (mostly the city of Bombay, or Mumbai in Marathi), Rajasthan, and Gujarat. Karnataka, traditionally a stronghold of Digambaras, has a sizable Jain community. [Source: Library of Congress]

Vinay Lal wrote: “Mahavira's teaching was confined to the Ganges valley and until the third century B.C.remained an oral tradition. The emphasis on non-violence prevented farmers from being Jains, since cultivation involved killing pests. However, Jainism spread among the traders and thus came to be associated with the spread of urban culture. Even today, Jains are associated with business, but they are also prominent in learning, and many of the most notable publishing houses in India, such as the renowned Indological booksellers Motilal Banarsidass, are owned and managed by Jains. [Source:Vinay Lal, professor of history, UCLA ==]

“In later years, Jainism moved to western India, where even today there are around two million Jains. Gandhi was deeply influenced by Jain religious thought and practices, and his advocacy of ahimsa, and his frequent recourse to fasting, owes a good deal to the Jaina philosophy. Jainism also spread to parts of Mysore in South India, a testament of which is the gigantic statue of a tirthankara (one of the 24 great Jaina teachers) at Sravanbelagola in near proximity to Mysore.==

“In later centuries, Jainism would undergo many changes. The strict rule against possessing property enforced by Mahavira was interpreted to mean only landed property. The Jains also divided into the orthodox Digambara (sky-clad, i.e, naked) sect and the more liberal Shvetambara (white-clad) sect. Important places of pilgrimage were to develop among the Jainas, among which Mt. Abu in Rajasthan and Sravanabelogola are prominent.” ==

Jain Beliefs

Jains believe that every soul is potentially divine and every individual has the potential to achieve “moksha” (nirvana) — the setting fee of the individual from “sanskura”, the cycle of birth and death — by following the teachings of the “tirthankaras”. The emphasis is on asceticism and arresting passion. Karma is not viewed as determinate but rather something that has be overcome and liberated from.

The Jains say that nature is complex and every objects has three aspects: a substance, its inherent qualities, and the infinite number of forms in can take in time and space. Jains have no creation myth because they believe the universe has no beginning or end and goes through an infinite number of cosmic cycles, each with periods of ascent and descent that are reflected in the rise and fall of human civilization. The 24 tirthankaras appear to help man cross the "great ford" to cosmic paradise during each half cycle.

The ancient belief system of the Jains rests on a concrete understanding of the working of karma, its effects on the living soul (jiva ), and the conditions for extinguishing action and the soul's release. According to the Jain view, the soul is a living substance that combines with various kinds of nonliving matter and through action accumulates particles of matter that adhere to it and determine its fate. Most of the matter perceptible to human senses, including all animals and plants, is attached in various degrees to living souls and is in this sense alive

See Separate Article: JAIN BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

Jain Sects

There are two main Jain sects: the “sky-clad” Digambaras and the “white-clad” Svetambaras. The schism dates back to the 4th century B.C. At the heart of the schism are different attitudes over matters related to asceticism and clothing. The basic doctrines of the two groups is basically the same. The Digambaras argue that going around without cloths frees one from sexual feeling and helps in the quest for enlightenment. The Svetambaras argued that detachment is a process that takes place in the mind and it does not matter whether one wears clothes or not. [Source: Marcus Banks, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992]

The Digambaras are the most conservative of the two groups. The highest order of Digambaras monks go naked to express their complete indifference to their bodies and are allowed to have only one possession, a pot with water for washing. They are not even allowed to possess a begging bowl. They must accept food and water in their cupped hands, By contrast Svetambaras monks and nuns wear simple white clothing. The two groups also differ in attitude towards the scriptures, views of the universe and attitude towards women (the Digambaras believe that no woman has ever achieved liberation and women have to become a men through reincarnation first).

The Svetambaras are further divided into one sect that rejects all forms of idolatry and another group, the “murti-pujaka” (idol worshipers), who build temples with idols of the tirthankaras. The schism her dates back to 15th century Gujarat. Those that oppose idol worship worry that the worshipers will worship idols in their own right and ascribe them with magical powers. Their places of worship are bare halls used for meditation .

Modern Jains

Many Jains are merchants, traders, wholesalers and moneylenders. Throughout Indian history they have been one of the most affluent groups in the country. Many Jains became traders because their religion forbade them from becoming farmers and soldiers. Some of India’s leading industrialists, bankers and jewelers are Jains. [Source: Marcus Banks, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992 |~|]

More Jains live in the cities than in the countryside. They are particularly concentered in Bombay, Delhi and Ahmedabad and other cities and towns in western India, where they are dominant figures in commerce, business and trade. Some lay Jains have migrated to east Africa, Britain and North America in search of business opportunities. Most of them are descendants of Jains from Gujarat.

Mahatma Gandhi was strongly influenced by the Jain leader Raychandbhai Mehta (1867-1901, a poet, scholar, political leader and holy man who promulgated non-violence. Born in Vavaniya, a village near Morbi, Mehta claimed he could remember his past lives at the age of seven. He performed Avadhāna, a memory retention and recollection test that gained him popularity, but he later discouraged it in favour of his spiritual pursuits. He wrote much philosophical poetry including Atma Siddhi. He also wrote many letters and commentaries and translated some religious texts. [Source: Wikipedia]

Jains, Diamonds and Surat

The Indian diamond business has traditionally been dominated by a handful of Jain families, which have been involved in the trading of pearls and precious stones for centuries. They have traditionally been very active in Surat in Gujarat, famous for its diamond cutting and polishing industries and has traditionally been the center of India’s diamond business.

Surat is widely known as the Diamond City of India. The streets of Old Surat are filled with businesses engaged in the diamond trade. Not so long ago, for less than US$1 a piece you could buy diamonds with 58-facets that fit into the pits on a strawberry. Varachha Road lies ta the center of Surat diamond factory district. The factories employ tens of thousands of workers and vary from upscale establishment to grimy sweatshops. Some require their workers all to wear the same colored uniforms. All are guarded.

India is the world largest diamonds and gemstone cutting center. At one time it polished and cut around 70 percent of the world diamonds as determined by weight. Centered in the western cities of Mumbai and Surat, the diamond industry provided India with 17 percent of its export earnings in the 1990s. These days India is getting more and more competition from China and Thailand.

The Indian diamond industry traces its origins back to the 1970s when a group of Jains set up an operation in Bombay and began to cut very small diamonds for export. They are credited with creating a market of small gems from industrial diamonds. The amount of processed diamonds rose from $39 million in 1970 to $3.5 billion in 1993. India held about 45 percent of the worlds' market in cut and polished diamonds in 1990. Lead by phenomenal growth in the export market, the country share rose to 70 percent in 1997. Most of the diamonds were supplied by the Rio Tinto-controlled Argyle mine in Western Australia and by South-Africa based De Beers, the world's largest player in the diamond trade at that time. Most of the stones cut and polished in India are small. The larger stones are cut primarily in Antwerp, Belgium

Image Sources: Wikicommons Media

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2023