CASTE SYSTEM AND PURITY

Brahmin ikshitar Hindu concepts about piety and the avoidance of pollution also lie at the heart of caste system. Karma itself is often defined as the purity or impurity of past deeds, with the idea being that one will be reincarnated at a lower level if they have been polluted in any way. A verse from the Upanishads, a sacred Hindu text, reads: "Those whose conduct on earth has given pleasure can hope to enter a pleasant womb, that its, the womb of a Brahmin or a woman of princely class. But those whose conduct on earth has been foul can expect to enter a foul and stinking womb of a bitch, a pig or an outcast."

Anything dealing with death, excrement, blood or dirt is regarded as impure. All bodily fluids are regarded as pollutants: urine, excrement, sweat, spit, blood, even tears. They feet are regarded as impure because the touch they ground. Devout Hindus not only avoid meat because it is associated with blood and death but also avoid potatoes, carrots, onions and ginger they are grow in the dirt.

The higher the caste the higher the levels of purity required of its members.

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Caste: Oxford India Short Introductions” by Surinder S. Jodhka Amazon.com ;

“Caste and Race in India” by G S Ghurye Amazon.com ;

“Religion, Caste, and Politics in India” by Christophe Jaffrelot Amazon.com ;

“Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age (The New Cambridge History of India)” by Susan Bayly Amazon.com ;

“Caste in India” by Dr. B R Ambedkar Amazon.com ;

“My Life with a Brahmin Family” by Lizzie Reymond Amazon.com ;

“Brahmin And Non-Brahmin” by M.S.S. Pandian Amazon.com ;

“Coming Out as Dalit: A Memoir of Surviving India's Caste System”

by Yashica Dutt, Janina Edwards, et al. Amazon.com

“Dalit: The Black Untouchables of India” by V.T. Rajshekar Amazon.com ;

"An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ;

“Hinduism for Beginners - The Ultimate Guide to Hindu Gods, Hindu Beliefs, Hindu Rituals and Hindu Religion” by Cassie Coleman Amazon.com ;

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com

Purity and Pollution in Indian Society

Many status differences in Indian society are expressed in terms of ritual purity and pollution. Notions of purity and pollution are extremely complex and vary greatly among different castes, religious groups, and regions. However, broadly speaking, high status is associated with purity and low status with pollution. Some kinds of purity are inherent, or inborn; for example, gold is purer than copper by its very nature, and, similarly, a member of a high-ranking Brahman, or priestly, caste is born with more inherent purity than a member of a low-ranking Sweeper (Mehtar, in Hindi) caste. Unless the Brahman defiles himself in some extraordinary way, throughout his life he will always be purer than a Sweeper. Other kinds of purity are more transitory — a Brahman who has just taken a bath is more ritually pure than a Brahman who has not bathed for a day. This situation could easily reverse itself temporarily, depending on bath schedules, participation in polluting activities, or contact with temporarily polluting substances. [Source: Library of Congress, 1995 *]

Purity is associated with ritual cleanliness — daily bathing in flowing water, dressing in properly laundered clothes of approved materials, eating only the foods appropriate for one's caste, refraining from physical contact with people of lower rank, and avoiding involvement with ritually impure substances. The latter include body wastes and excretions, most especially those of another adult person. Contact with the products of death or violence are typically polluting and threatening to ritual purity.*

During her menstrual period, a woman is considered polluted and refrains from cooking, worshiping, or touching anyone older than an infant. In much of the south, a woman spends this time "sitting outside," resting in an isolated room or shed. During her period, a Muslim woman does not touch the Quran. At the end of the period, purity is restored with a complete bath. Pollution also attaches to birth, both for the mother and the infant's close kin, and to death, for close relatives of the deceased.*

Caste Rules

the concept of purity is one reason why bathing in the Ganges is so important

Although castes are usually defined by occupation, there are usually distinct styles of dress, behavior, language, religious customs, celebrations. and diet that are associated with each one. Caste determines who an individual can marry, where they can live and which job they can take. There are caste restrictions for smoking, drinking, eating and socializing with other castes. The rules are set up to define the inter-relations between castes based on concepts of purity and pollution (higher up castes are regarded as more pure and interacting with lower castes defiles this purity and is regarded as polluting). Sometimes it seems the rules ignore the needs of different castes to interact and provide goods and services for one another.

A great many other traditional rules pertaining to purity and pollution constantly impinge upon interaction between people of different castes and ranks in India. Although to the non-Indian these rules may seem irrational and bizarre, to most of the people of India they are a ubiquitous and accepted part of life. Thinking about and following purity and pollution rules make it necessary for people to be constantly aware of differences in status. With every drink of water, with every meal, and with every contact with another person, people must ratify the social hierarchy of which they are a part and within which their every act is carried out. The fact that expressions of social status are intricately bound up with events that happen to everyone every day — eating, drinking, bathing, touching, talking — and that transgressions of these rules, whether deliberate or accidental, are seen as having immediately polluting effects on the person of the transgressor, means that every ordinary act of human life serves as a constant reminder of the importance of hierarchy in Indian society. [Source: Library of Congress, 1995 *]

Each caste is believed by devout Hindus to have its own dharma, or divinely ordained code of proper conduct. Accordingly, there is often a high degree of tolerance for divergent lifestyles among different castes. Brahmans are usually expected to be nonviolent and spiritual, according with their traditional roles as vegetarian teetotaler priests. Kshatriyas are supposed to be strong, as fighters and rulers should be, with a taste for aggression, eating meat, and drinking alcohol. Vaishyas are stereotyped as adept businessmen, in accord with their traditional activities in commerce. Shudras are often described by others as tolerably pleasant but expectably somewhat base in behavior, whereas Dalits — especially Sweepers — are often regarded by others as followers of vulgar life-styles. Conversely, lower-caste people often view people of high rank as haughty and unfeeling.

The Laws of Manu, compiled at least 2,000 years ago by Brahmin priests, describes rules for each varna on eating, marrying, making money, maintaining piety and what to avoid. The Dharma shastras, the Hindu books of law written between A.D. 100 and 500, defines how each caste is supposed to act according to an established a set of rules on dictates how different castes should treat one another

Old caste customs in Kerala

Caste rules are very strict. Members of different castes are not even eat with one another. Marriages generally take place only between members of the same caste. Even things like the length of a sari, the details of the marriage ceremony, the ornaments a women can wear, whether or not a person can carry an umbrella, when water is drawn from a well and which door of a temple a person can enter are determined by caste rules. What is acceptable for one caste system may be taboo for another. The study of the Vedas is expected of Brahmin but is a sinful pursuit for members of lower castes. Conversely, drinking alcohol is generally okay for low caste members but is a great sin for Brahmins.

Activities such as farming or trading can be carried out by anyone, but usually only members of the appropriate castes act as priests, barbers, potters, weavers, and other skilled artisans, whose occupational skills are handed down in families from one generation to another. As with other key features of Indian social structure, occupational specialization is believed to be in accord with the divinely ordained order of the universe.*

Food and Drink and the Maintenance of Purity in India

Maintenance of purity is associated with the intake of food and drink, not only in terms of the nature of the food itself, but also in terms of who has prepared it or touched it. This requirement is especially true for Hindus, but other religious groups hold to these principles to varying degrees. Generally, a person risks pollution — and lowering his own status — if he accepts beverages or cooked foods from the hands of people of lower caste status than his own. His status will remain intact if he accepts food or beverages from people of higher caste rank. Usually, for an observant Hindu of any but the very lowest castes to accept cooked food from a Muslim or Christian is regarded as highly polluting. [Source: Library of Congress, 1995 *]

In a clear example of pollution associated with dining, a Brahman who consumed a drink of water and a meal of wheat bread with boiled vegetables from the hands of a Sweeper would immediately become polluted and could expect social rejection by his caste fellows. From that moment, fellow Brahmans following traditional pollution rules would refuse food touched by him and would abstain from the usual social interaction with him. He would not be welcome inside Brahman homes — most especially in the ritually pure kitchens — nor would he or his close relatives be considered eligible marriage partners for other Brahmans.*

Generally, the acceptance of water and ordinary foods cooked in water from members of lower-ranking castes incurs the greatest pollution. In North India, such foods are known as kaccha khana , as contrasted with fine foods cooked in butter or oils, which are known as pakka khana . Fine foods can be accepted from members of a few castes slightly lower than one's own. Local hierarchies differ on the specific details of these rules.*

Completely raw foods, such as uncooked grains, fresh unpeeled bananas, mangoes, and uncooked vegetables can be accepted by anyone from anyone else, regardless of relative status. Toasted or parched foods, such as roasted peanuts, can also be accepted from anyone without ritual or social repercussions. (Thus, a Brahman may accept gifts of grain from lower-caste patrons for eventual preparation by members of his own caste, or he may purchase and consume roasted peanuts or tangerines from street vendors of unknown caste without worry.)

Water served from an earthen pot may be accepted only from the hands of someone of higher or equal caste ranking, but water served from a brass pot may be accepted even from someone slightly lower on the caste scale. Exceptions to this rule are members of the Waterbearer (Bhoi, in Hindi) caste, who are employed to carry water from wells to the homes of the prosperous and from whose hands members of all castes may drink water without becoming polluted, even though Waterbearers are not ranked high on the caste scale.*

.jpg)

snake charmer caste: From “Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India” (1837)

Caste and Marriage

There are often very strict rules barring marriages between members of different castes, even if the bride and groom come from similar level castes.

Arranged marriage and child marriages have traditionally been set up in part to ensure the caste system status quo.

Hypergamy is a a system that allows women to marry men of higher caste but not a lower caste.

The cost of breaking these rules is often death. In January 2001 in a village in Rajpura, a young man and young girl were killed by their families and cremated the bodies to destroy the evidence. The young man and woman had just gotten married. The groom was from the Gulkra caste which is few notches above the bride's Nai caste. Murders like this are rarely punished because village usually band together to keep word of the incident leaking out.

Mixed caste marriages and romances still result in death. In the early 2000s, a 19-year-old Brahmin man and his 18-year-old Jat lover were hang from a roof in front of a crowd of several hundred people in Alipur village in Uttar Pradesh state. Families of the couple not only dd not try t stop to, they were arrested or encouraging participating in the hanging.

Outcastes and Breaking Caste Rules

What happens if you break the systems of caste. If the rules of contact are broken the penalties among strict Hindu followers can be quite severe. Breaking caste brings pollution for which requires penances even if it is incurred accidently. In extreme cases people are excommunicated. Hindus believe that the world and human society are divine structures. The are reincarnated through this structure until they reach a state of total divinity. Disruptions of the process can cause great alarm. In ancient times Hindus was forbidden from "crossing the waters" (traveling abroad) out of fear they would lose their caste rank and have to begin again at the bottom.

Within castes explicit standards are maintained. Transgressions may be dealt with by a caste council (panchayat), meeting periodically to adjudicate issues relevant to the caste. Such councils are usually formed of groups of elders, almost always males. Punishments such as fines and outcasting, either temporary or permanent, can be enforced. In rare cases, a person is excommunicated from the caste for gross infractions of caste rules. An example of such an infraction might be marrying or openly cohabiting with a mate of a caste lower than one's own; such behavior would usually result in the higher-caste person dropping to the status of the lower-caste person. [Source: Library of Congress]

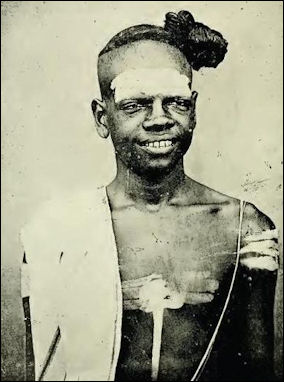

.jpg)

From “Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India” (1837)

The word outcast is said to be derived from people who were thrown out of their caste group for breaking caste rules. According to Carol Pozefsky, entomology expert at allexperts.com: “Outcast stems from the Scandanavian word casten which first appears in a 13th century book called Ancrene Riwle . Casten meant 'throw' and was related to the Old Icelandic word 'kasta' also meaning to throw. The word 'castaway' as a noun appears before 1475 and 'outcast' simply one who is cast out (or thrown out) is first noted in 16th century English literature.

The prefix 'out' stems from the Old English word 'ut' The Middle Dutch uut, the Old High German uz and the Swedish and Norwegian ut and Danish ud. They all mean the same thing, OUT!”

Caste Rules, Racism and Discrimination

Some have argued that the caste system is not supported by Hinduism but that it endures because of high caste racists. The anthropologist John Reader said "social barriers can be as difficult to cross as geographical boundaries." The customs says Reader "have evolved beyond mere prohibitions and taboos into notions that members of one caste could be physically and even spiritually polluted by contact with the members of another, supposedly inferior caste. Many Hindus believe that contact with a person of a lower caste is almost the same as contacting someone with a contagious disease. It is believed that the lowest of lows, the Dailts (Untouchables), bring defilement and contamination to the people they touch.

Different castes drink from different wells. Some temples have two doors. One is for menstruating women and people from lower castes. In some cases higher castes are not even supposed to let the shadows of lower castes fall on them. Some Indians go through great lengths not to touch their lips to a drinking cup (they pour the water into their mouth) so as not to pollute the water consumed by other castes. Since rice is cooked with water there are special rules on who can eat with whom. Some upper castes only eat rice they prepare themselves.

Because of concerns of pollution being transferred from not only from people of lower castes but also from menstruating women, people with recently deceased relatives or people who have touched sweat or other body excretions, tea sold from street vendors is often served in a clay cups and disposed of afterwards of high castes don't want to risk drinking out of the same cup of a polluting person or a person of a low caste . Food is often served on a disposable banana leaf for the same reason.

.jpg)

From “Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India” (1837)

Every Indian language has word to expression purity and impurity. “Pure” usually means “clean, spiritually meritorious” while “impure” means “unclean, defiled, polluted” and even “sinful.” The distance between castes is measured in terms of purity and impurity. Not only are higher castes regarded as more pure than lower castes, the same holds true for their professions, diets and lifestyles. Caste rules are often defined by the distance between castes in terms of purity and impurity.

Ideas about giving and receiving and serving and being served are important in the caste system. Castes can often be ranked by the transactions between castes in terms of one being a giver and one receiving goods, services, gifts, ad spiritual blessings.

Never enter the kitchen of someone of high caste. If you touch something there you may effectively pollute the entire kitchen and a special cleansing ceremony is required by a Brahmin priest to purify it again. Before that time no food can be prepared there.

Castes in a Typical Indian Village

Members of a caste are typically spread out over a region, with representatives living in hundreds of settlements. In any small village, there may be representatives of a few or even a score or more castes.

Each village usually has members of 20 castes or so living there full time — farmers, bakers, tailors, merchants, tax-collectors, shoemakers, government officials, animal herders, servants, laborers, and artisans. Each caste has ties with same caste in villages nearby. Nomadic castes such as snake-charmers, bear trainers, merchants, medicine salesmen and dancers enter the villages from time to time.

The villages have a vertical unity provided by many castes and horizontal unity provided by caste alliances with other villages. Villages are typically divided into communities made up of members of the same castes, with the dominant castes living in the center of the villages, and the lower castes and Untouchables on the fringes. Towns and cities are often divided into neighborhoods made up of members of the same castes, with the dominant castes living in nice neighborhoods and the lower castes and Untouchables in the slums.

sonars (goldsmith caste) at work in 1873

Because agriculture is the primary way of life peasants are the dominant caste. In a typical village with 600 households and 4,000 people there might be 22 Brahmin households and one Kshatryas household. Other households are identified by subcaste: 16 Banias (merchants and businessmen); 40 Mallas (fishermen); 20 Koiris (farmers); 25 telis (oil seed crushers who use bullock powered presses); 20 Lohars (blacksmiths); 15 Ahirs (cowherds); 10 Dhobis (washermen); 10 Khatiks (fruit and pig dealers); 5 Gawals (sheep herders); 3 Bhats (singers and dancers for perform at weddings); 2 Nias (barbers); 2 Doms (cremation attendants); and 1 Gond (peanut seller). In addition there are might be 50 Muslim weaver and tailor households and 200 Untouchable households. [Source: John Putman, National Geographic October 1971]

Caste position is often determined more by economic position than tradition. In some villages upper caste families and Untouchable families are kinked in master-servant relationships.

Caste Councils

Caste councils are found in almost every village and town. They are made up of the male heads of the most prominent families in each caste. Their primary function is to make sure good relations are maintained between the castes by following traditional patterns of behavior. Fines and minor physical punishments may be handed down to minor infractions. The breaking of taboos is punished with pubic humiliation such as beating with sandals or worse.

The leaders of the dominant castes are often spokespersons for the village and owe their power not to legal rights derived for the state but to dominant local position in their caste. The elders of the dominant castes administer justice not only to members of their own caste but also to members other castes who seek their intervention.

Changes, Ranking and Caste

Different castes are ranked hierarchically with each caste being superior to some castes and inferior to others. Similar profession are delineated by their purity. For example goldsmiths are a higher caste than blacksmiths. The system is not uniform. Because different caste are found in different areas, one caste may be superior to one caste in one place but inferior to another in another places.

Although a person’s association with a caste is fixed at birth the positions of different castes within he caste system are changeable. Some castes become wealthy and give up manual labor and take up “cleaner professions.” Others adopt purer customs such as a vegetarian diet, holding public prayers presided over by a Brahmin priests and other high customs as a way of moving up the caste ladder.

Brahmanen

Some Indians leave India or convert to Islam, Buddhism, or Kshatriya or pursue a Western education and Western professions to escape from the caste system. It has been argued that other religions, Westernization and secularization are aimed at getting rid of the caste system all together.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and the 19th century book Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2015