MODERN CHANGES IN HINDUISM

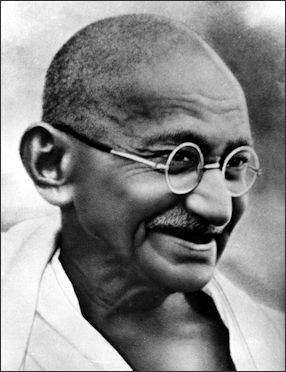

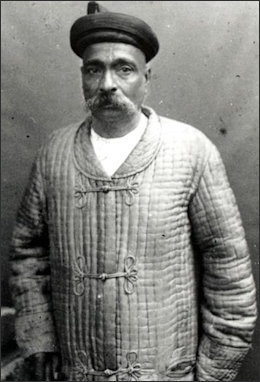

Gandhi

The process of modernization in India, well under way during the British colonial period (1757-1947), has brought with it major changes in the organizational forms of all religions. The missionary societies that came with the British in the early nineteenth century imported, along with modern concepts of print media and propaganda, an ideology of intellectual competition and religious conversion. Instead of the customary interpretation of rituals and texts along received sectarian lines, Indian religious leaders began devising intellectual syntheses that could encompass the varied beliefs and practices of their traditions within a framework that could withstand Christian arguments. [Source: Library of Congress *]

One of the most important reactions was the Arya Samaj (Arya Society), founded in 1875 by Swami Dayananda (1824-83), which went back to the Vedas as the ultimate revealed source of truth and attempted to purge Hinduism of more recent accretions that had no basis in the scriptures. Originally active in Punjab, this small society still works to purify Hindu rituals, converts tribal people, and runs centers throughout India. Other responses include the Ramakrishna order of renunciants established by Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), which set forth a unifying philosophy that followed the Vedanta teacher Shankara and other teachers by accepting all paths as ultimately leading toward union with the undifferentiated brahman. One of the primary goals of the Ramakrishna movement has been to educate Hindus about their own scriptures; the movement also runs book stores and study centers in all major cities. Both of these paths are directly modeled on the institutional and intellectual forms used by European missionaries and religious leaders. *

The perception that one's religion is in danger receives periodic reinforcement from the phenomenon of public mass religious conversion that receives coverage from the news media. Many of these events feature groups of Scheduled Caste members who attempt to escape social disabilities through conversion to alternative religions, usually Islam, Buddhism, or Christianity. These occasions attract the attention of fundamentalist organizations from all sides and heighten public consciousness of religious divisions. The most conspicuous movement of this sort occurred during the 1950s during the mass conversions of Mahars to Buddhism. In the early 1980s, the primary example was the conversion of Dalits to Islam in Meenakshipuram, Tamil Nadu, an event that resulted in considerable discussion in the media and an escalation of agitation in South India. Meanwhile, conversions to Christianity among tribal groups continue, with growing opposition from Hindu revivalist organizations. *

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ;

“India: A History" by John Keay Amazon.com ;

"The Wonder That Was India" by A.L. Basham Amazon.com ;

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook” translated from the Sanskrit by Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics, 2004) Amazon.com ;

“Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization” by Heinrich Zimmer (Princeton University Press, 1992) Amazon.com ;

“Indian Mythology” by Veronica Ions (Peter Bedrick 1984) Amazon.com

Swaminarayan

Swaminarayan

Lord Swaminarayan (1781-1830) was the founder of the Swaminarayan tradition. Born Ghanshyam Pande in the village of Chhapaiya in Uttar Pradesh in Northern India, near Ayodhya, into a Brahmin family, he travelled extensively around India in his youth and eventually settled in an ashram in Gujarat. He was known as a social and moral reformer by the people of Gujarat, and by the British administration in that region. At the age of 21, he founded the Swaminarayan Sampradaya (or denomination) to promote his teachings. He initiated 3,000 sadhus (monks) and is recognised and worshipped as God by his followers. To continue his work of promoting personal morality and moulding spiritual character, he promised to remain ever-present with his followers through an unbroken succession of enlightened gurus. [Source: BBC]

Swaminarayan, also known as Sahajanand Swami, was a yogi, and an ascetic whose life and teachings brought a revival of central Hindu practices of dharma, ahimsa and brahmacharya. In 1792, he began a seven-year pilgrimage across India at the age of 11 years, adopting the name Nilkanth Varni. During this journey, he did welfare activities and after 9 years and 11 months of this journey, he settled in the state of Gujarat around 1799. In 1800, he was initiated into the Uddhav sampradaya by his guru, Swami Ramanand, and was given the name Sahajanand Swami. In 1802, his guru handed over the leadership of the Uddhav Sampraday to him before his death. Sahajanand Swami held a gathering and taught the Swaminarayan Mantra. From this point onwards, he was known as Swaminarayan. The Uddhav Sampraday became known as the Swaminarayan Sampraday. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Swaminarayan developed a good relationship with the British Raj. He had followers not only from Hindu denominations but also from Islam and Zoroastrianism. He built six temples in his lifetime and appointed 500 paramahamsas to spread his philosophy. In 1826, Swaminarayan wrote the Shikshapatri, a book of social principles.He died on 1 June 1830 and was cremated according to Hindu rites in Gadhada, Gujarat. Before his death, Swaminarayan appointed his adopted nephews as acharyas to head the two dioceses of Swaminarayan Sampraday. Swaminarayan is also remembered within the sect for undertaking reforms for women and the poor, and performing yajñas (fire sacrifices) on a large scale. +

Development of Modern Hinduism

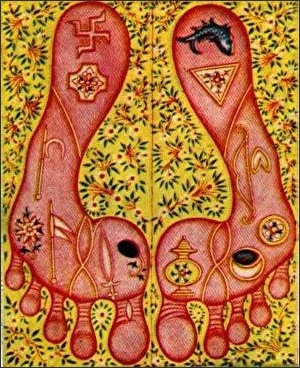

Swaminarayan's lotus-shaped feet

Vinay Lal, a professor at UCLA, wrote:“Modern Hinduism developed, in more ways than is customarily understood, under the crucible of colonial rule. By the late eighteenth century, considerable portions of India had fallen under British rule, and the British ‘discovery’ of Hinduism dates to this period. Translations of various classes of Hindu religious literature into European languages were first attempted at this time, just as lengthy accounts purporting to offer insights into Hindu customs, manners, and mores were also beginning to appear. Though the establishment of British rule would eventually ease the way for Christian missionaries, until 1813 the East India Company was not favorably disposed towards missionary activity. Indians were perceived as being particularly religious-minded, and British officials were certain that nothing was calculated to jeopardize British rule in India as much as creating insecurity of religious belief and expression among their subjects. [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

“According to conventional scholarly accounts that are still not without their adherents, early British Orientalists or Indologists, such as Sir William Jones, Charles Wilkins, Nathaniel Halhead, and Charles Wilkins, who never doubted the superiority of their culture and intellectual attainments, were nevertheless enthusiastic about the achievements of the ancient Hindus. By the early nineteenth century, however, British rule was firmly in place and racial feelings had become more pronounced. There was much less hesitation in denouncing Hinduism as a polytheistic faith ridden with superstitions, and scores of works drew attention to barbarous practices alleged to have been inspired or sanctioned by the Hindu faith, including sati (widow-immolation), female infanticide, human sacrifice, child marriages, hook-swinging, polygamy (among some classes of Brahmins), and prohibitions designed to prevent widows, including pre-pubescent girls, from remarriage. European observers, quite unmindful of the clearly subservient status of their own women, had nevertheless concluded that one reliable evaluative scale for judging civilizations consisted in assessing how they treated their women. In this respect, India was found gravely wanting.

Hindu Reformers

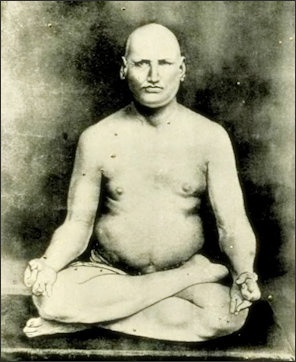

Professor Lal wrote: “The Bengali Brahmin, Rammohan Roy (1772-1833), was perhaps the most illustrious of the early reformers who accepted that European rule in India had fortuitously compelled Hindus to recognize the shortcomings in Indian society. While Roy was unable to accept the charge that Hinduism was intrinsically flawed, he acknowledged that the original teachings of the Vedas had been corrupted; and while receptive to the ethical content of Christianity, he rejected its doctrinal teachings. Roy undertook a careful scholarly study of the Hindu scriptures and came to the conclusion that Hinduism, far from being a polytheistic faith, was fundamentally monotheistic. He did not pause to consider, however, that ‘polytheism’ and ‘monotheism’ alike are not categories through which Hindus would have described themselves. His opposition to sati, which was to lead to its abolition in the territories of the East India Company, enraged the Hindu orthodoxy. Roy was also a proponent of education in English, since he wished to bring Western scientific and humanistic learning to India. [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

Ram Mohan Roy

“In 1828, Roy established an organization called the Brahmo Sabha [Society] dedicated to the Worship of One God. Apart from its advocacy of a simpler, more Unitarian-like form of Hinduism, the Brahmo Sabha promoted modern learning and fought strenuously for the removal of traditional disabilities against women. In the emergent middle-class Hindu society of Bengal, girls were now educated and child marriages were debated if not always repudiated. The Tattvabodhini Sabha, founded in 1839, aimed both to familiarize Hindus with their scriptures through inexpensive publications and stem the expansion of Christianity in India. Debendranath Tagore (1817-1905), the father of the famous poet Rabindranath Tagore, endeavored to bring the two organizations together in 1843 and created something like a charter of faith for the newly energized Brahmo Samaj. Under the controversial leadership of Keshub Chunder Sen (1838-1884), the Brahmo Samaj experienced a number of schisms, even as its influence was experienced in other parts of India and its agenda of social reform became bolder. In western India, for example, the liberal-minded Mahadev Govind Ranade (1842-1901) established a similar organization by the name of Prarthana Samaj (‘Prayer Society’) in 1869, and there, too, debates over widow remarriage, child marriage, and female education were soon to occupy center stage.==

“Hindu reform movements did not, however, always look to the West, as the history of the Arya Samaj amply demonstrates. Its founder, a village Gujarati Brahmin by the name of Dayananda Saraswati (1824-1883), condemned nearly all developments in post-Vedic Hinduism. Dayanand held the Vedas to be the Word of God, absolutely free from error and an authority to the end of time, and he set out his teachings in Satyartha Prakash (“The Light of Truth”, 1875), a massive reinterpretation of the Vedas for modern times. Though the Arya Samaj, founded in the same year, is often described as a revivalist movement, Dayanand thought of himself as a modernist. He found no sanction for idol-worship, the practice of untouchability, child marriage, or even the subjection of women in the Vedas; on the contrary, he was quite certain that the social scientific learning of the West had been anticipated in the Vedas. The reformist and crusading impulses of the Arya Samaj, which sent out missionaries throughout north India and even among diasporic Indian populations in Fiji, Trinidad, South Africa, and elsewhere, are seen today in the figure of Swami Agnivesh (1941-), a fiery activist known as much for his critiques of Hindu superstitions as for his work in procuring the freedom of bonded laborers.

Divergent Stands of Hinduism: Nationalism, Devotionalism, and Spiritual Masters

Professor Lal wrote: “Two of Dayanand’s contemporaries at the other end of India, in Bengal, point to the diverse developments taking place under the rubric of Hinduism. The renowned novelist and essayist Bankimcandra Chatterjee (1838-94), while not a supreme figure in the history of modern Hinduism as such, nonetheless eloquently voiced the anguish of middle-class Hindus in posing the question, ‘Just how had India repeatedly succumbed to foreigners?’ In works such as Krsnacaritra (“Life of Krishna”, 1886), Bankim argued that the Hindu’s attachment to the philosophy of bhakti (devotion) had rendered the once vigorous race of Aryans into an effeminate people who, lost in rapturous and ecstatic devotion, had become incapable of defending their faith. Bankim called for the affirmation of a more masculine Hinduism. [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

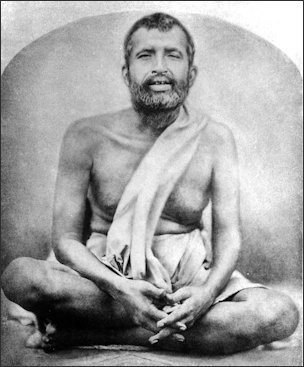

“Meanwhile, in another part of Calcutta, one of the most remarkable figures of modern history was steering Bengali youth back towards bhakti. Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa (1836-1886), who was far removed from the elite circles of Bengali society, came to acquire a large following among the modernizing, middle-class Bengali families as a Hindu mystic. Ramakrishna came to embody a sheer spiritual ecstasy that appeared to offer one answer to the growing materialism of Bengali life and the investment of the educated in scientific rationality. At the Dakshineshwar temple on the outskirts of Calcutta, where his brother Ramkumar had served as priest, Ramakrishna became a devout follower of the goddess Kali. His devotion was so intense that he would remain immersed in samadhi, a state which Hindus describe as transcending all consciousness -- paradoxically, also a state of constant awareness, a form of supra-consciousness. Ramakrishna hearkened back to a form of androgynous Hinduism, and is described as being capable of taking on feminine attributes. In the company of women, it is said of Ramakrishna, he appeared to them as one of their own; and he could so embrace the feminine that he would menstruate, blood oozing out of the pores of his skin.==

“Ramakrishna’s oral discourses, faithfully captured by a number of disciples, on ethical conduct, mystical illumination, rapturous devotion, the goddess, and the wicked ways of the world became legendary. Among those who heard his summons was Narendra Dutta (1863-1902), who found Ramakrishna’s mysticism entirely compatible with the demands of reason. As Swami Vivekananda, he was charged with spreading not only his master’s teachings but the idea that a resurgent Hinduism would lead India into fulfilling its mission of energizing the world through a form of political spiritualism. While keen to furnish Hinduism with a message of social service, which would be dispensed through the Ramakrishna Mission, founded in 1892, Vivekananda became a tireless proponent of a Hinduism that he envisioned as once both muscular and the repository of timeless truths. He accepted that Hinduism had become degraded over time, and that the West’s domination of the material domain had given it the veneer of superiority. The inner core of Hinduism, Vivkenanda submitted, nonetheless remained spotless. To a world weary of violence, Viveknananda put forward Hinduism as an intrinsically tolerant faith. Vivekananda took his message to the West, and his fame spread after an electrifying address he gave in Chicago at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893, where he stood forth as the principal representative of Hinduism. He lectured widely in the West and won many converts to his thinking. To the present day, he remains one of the favorite icons of diasporic Hindus.” ==

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) , is well known for his interpretation of Hinduism for Western audiences and was a key figure in introducing Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and the United States, raising interfaith awareness and making Hinduism a world religion. He was strongly influenced by Raja Rammohan Roy (1772–1833), known as the father of the Hindu Renaissance.

According to Oxford’s Gavin Flood, Swami Vivekananda was "a figure of great importance in the development of a modern Hindu self-understanding and in formulating the West's view of Hinduism". Central to his philosophy is the idea that the divine exists in all beings, that all human beings can achieve union with this "innate divinity", and that seeing this divine as the essence of others will further love and social harmony. According to Vivekananda, there is an essential unity to Hinduism, which underlies the diversity of its many forms. According to Flood, Vivekananda's vision of Hinduism "is one generally accepted by most English-speaking middle-class Hindus today". Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan sought to reconcile western rationalism with Hinduism, "presenting Hinduism as an essentially rationalistic and humanistic religious experience". [Source: Wikipedia]

Vivekananda is today often misinterpreted as a proto-Hindu nationalist. Karan Mahajan wrote in The New Yorker that he had “a tortured trajectory. Born in 1863, he grew up in Calcutta in a privileged family and proceeded, over his lifetime, to study everything from the Vedas and the Upanishads to Freemasonry, Buddhist meditation, Hegel, and Thomas à Kempis’s “The Imitation of Christ.” He could, Khilnani writes, “recite pages from The Pickwick Papers as readily as sutras from Panini’s Ashtadhyayi.” But after he finished college, both his father and mentor died in quick succession. Suffering a breakdown, Vivekananda retreated to the banks of the Ganga to worship under the spiritualist Ramakrishna Paramhansa. He became a mendicant and began wandering India, and was “driven mad with mental agonies” over what he encountered: ritual, poverty, disease. Hinduism appeared to provide none of the salves it promised; instead, the caste system and child marriage had oppressed the majority of the population. Vivekananda began to turn away from mainstream Hindus and Brahmins and to pursue a purer form of Hinduism, one that was practical and geared toward social uplift. [Source: Karan Mahajan , The New Yorker , November 1, 2016]

This was the revelation he supposedly had on the southernmost tip of India, one that, the next year, sent him sailing to the U.S. to spread the word about Hinduism at the Parliament of World’s Religions, in Chicago, in 1893. He crashed the Parliament and became one of its stars, earning the admiration of Henry and William James, who hung “on his utterances.” During pauses in his lecture circuit, he wrote the central text of modern yoga, “Raja Yoga.” But Vivekananda also kept his eyes open. He came back to India impressed with the “social openness, the comparative freedom of women, the ability of people to act collectively in their own interests,” and the relative dignity afforded to the lower classes in America. He began recommending the American habits of eating beef and bodybuilding to Indians. He was, in every way, a more liberal figure—well-read, curious, sensitive—than he is remembered as today.

Development of Political Hinduism

In a review of the book: “The Hindus: An Alternative History” by Wendy Doniger, Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times, “The Hindu nationalists of today, who long for India to become a muscular international power, stand in a direct line of 19th-century Indian reform movements devoted to purifying and reviving a Hinduism perceived as having grown too fragmented and weak. These mostly upper-caste and middle-class nationalists have accelerated the modernization and homogenization of “Hinduism.” [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, April 24, 2009 ***]

Ramakrishna Paramhansa

“Still, the nontextual, syncretic religious and philosophical traditions of India that escaped the attention of British scholars flourish even today. Popular devotional cults, shrines, festivals, rites and legends that vary across India still form the worldview of a majority of Indians. ..Far from being a slave to mindless superstition, popular religious legend conveys a darkly ambiguous view of human action. Revered as heroes in one region, the characters of the great epics “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” can be regarded as villains in another. Demons and gods are dialectically interrelated in a complex cosmic order that would make little sense to the theologians of the so-called war on terror. ***

“Doniger sets herself the ambitious task of writing “a narrative alternative to the one constituted by the most famous texts in Sanskrit.” As she puts it, “It’s not all about Brahmins, Sanskrit, the Gita.” It’s also not about perfidious Muslims who destroyed innumerable Hindu temples and forcibly converted millions of Indians to Islam. Doniger, who cannot but be aware of the political historiography of Hindu nationalists, the most powerful interpreters of Indian religions in both India and abroad today, also wishes to provide an “alternative to the narrative of Hindu history that they tell.” ***

“She writes at length about the devotional “bhakti” tradition, an ecstatic and radically egalitarian form of Hindu religiosity which, though possessing royal and literary lineage, was “also a folk and oral phenomenon,” accommodating women, low-caste men and illiterates. She explores, contra Marx, the role of monkeys as the “human unconscious” in the “Ramayana,” the bible of muscular Hinduism, while casting a sympathetic eye on its chief ogre, Ravana. And she examines the mythology and ritual of Tantra, the most misunderstood of Indian traditions. ***

“She doesn’t neglect high-table Hinduism. Her chapter on violence in the “Mahabharata” is particularly insightful, highlighting the tragic aspects of the great epic, and unraveling, in the process, the hoary cliché of Hindus as doctrinally pacifist. Both “dharma” and “karma” get their due. Those who tilt at organized religions today on behalf of a residual Enlightenment rationalism may be startled to learn that atheism and agnosticism have long traditions in Indian religions and philosophies. ***

“Doniger’s chapter on the centuries of Muslim rule over India helps dilute the lurid mythology of Hindu nationalists. Motivated by realpolitik rather than religious fundamentalism, the Mughals destroyed temples; they also built and patronized them. Not only is there “no evidence of massive coercive conversion” to Islam, but also so much of what we know as popular Hinduism — the currently popular devotional cults of Rama and Krishna, the network of pilgrimages, ashrams and sects — acquired its distinctive form during Mughal rule. ***

“Yet it is impossible not to admire a book that strides so intrepidly into a polemical arena almost as treacherous as Israel-―Arab relations. During a lecture in London in 2003, Doniger escaped being hit by an egg thrown by a Hindu nationalist apparently angry at the “sexual thrust” of her interpretation of the “sacred” “Ramayana.” This book will no doubt further expose her to the fury of the modern-day Indian heirs of the British imperialists who invented “Hinduism.” Happily, it will also serve as a salutary antidote to the fanatics who perceive — correctly — the fluid existential identities and commodious metaphysic of practiced Indian religions as a threat to their project of a culturally homogenous and militant nation-state.”

Book: “The Hindus: An Alternative History” by Wendy Doniger, Penguin Press,, 2009]

Hinduism in the Early 20th Century

Gangadhar Tilak

“As nationalism gained ground towards the end of the nineteenth century, Hindu thinkers sought to accommodate Hinduism to their political thinking. Under Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928), the Arya Samaj mobilized nationalist sentiment against British rule and became a considerable political force in north India. Though Lajpat Rai was immensely popular, Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920), a learned Chitpavan Brahmin from Maharashtra, acquired an unprecedented following. He gave support to Dayanand’s anti-cow killing campaign, but the real stroke of political genius on his part was to revive both the Ganapati festival (celebrating the popular deity Ganesh), which would become an annual occasion for haranguing the British, and the memory of Shivaji, a seventeenth century chieftain who was transformed by Tilak’s panegyrics and the anti-colonialism of rapturous Hindu devotees into a nationalist figure who had shown the way to defend the motherland against rapacious outsiders. The suppression of these celebrations by the British, Tilak realized, could be charged against them as an attempt to tamper with the religious sensibilities of Indians. [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

“In Bengal, the highly westernized Aurboindo Ghose (1872-1950), whose father kept him away from India for nearly fifteen years, immersed himself in Hindu texts and then plunged into nationalist politics. The pages of his English-language weekly, Bande Mataram (“Hail the Motherland”), became a rallying point for Hindu revolutionaries who invoked the goddess and advocated swadeshi (self-reliance). Aurobindo’s retreat from politics was just as dramatic as his entry: allegedly upon the advice of a holy man, Aurobindo left for the French enclave of Pondicherry in southern India and withdrew into seclusion to practice yoga. Over the course of the next four decades, Aurobindo endeavored to perfect yoga so that it would lead to an inner development by means of which the practitioner could discover the ‘one self that’ inhabits all and evolve a consciousness that Aurobindo described as supramental. Though Aurobindo also sought to articulate his philosophical worldview in a huge corpus of writings, he was, like virtually every other major figure in contemporary Hinduism, including Bankimcandra, Tilak, and Gandhi, drawn most eminently to the Bhagavad Gita. Indeed, a history of contemporary Hinduism can be written through the Gita: discussed widely in nationalist circles, revolutionaries drew upon its teachings to justify armed opposition to the British, while Gandhi insisted on an allegorical reading that turned the Gita into a manual of nonviolence. While a contemporary Vaishnava theologian such as Srila Prabhupada (1896-1977) of the Caitanya-sampradaya, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement, views the Gita as the supreme embodiment of the idea of bhakti (devotion), others such as Gandhi and Tilak have seen the Gita as a call to action (karma yoga).==

“The first half of the twentieth century can also be described as a period of modern spiritual masters, of the emergence of Hindu apologetics, and of Hinduism, or a form of ‘Indian spirituality’, going transnational. Various figures, such as Swami Sivananda (1887-1963), the founder of the Divine Life Society Movement; the philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975), author of the widely read The Hindu View of Life (1927); Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986), who owed no particular allegiance to Hinduism, or to caste, religion, or nation, but nonetheless became widely renowned as the repository of ‘Indian wisdom’; and the monks of the Ramakrishna Mission can be evoked in this context. Two extraordinarily compelling figures emerge from this period of Hinduism. The Sai Baba of Shirdi (1894-1969) stressed the harmony of Hinduism and Islam and would be claimed by both Muslims and Hindus. Speaking in parables, he became known as a healer and performer of miracles; and from his base in a village in Maharashtra, he came to have a worldwide following among Hindus. Further south, in Tamil Nadu, the sage of Arunachala, Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950), offered the clearest exposition of advaita (non-dualism). Describing his method as Self-inquiry, Maharshi taught that we are the Supreme Self, and that awareness of this reality necessitates not the abandonment of our duties in this life or the cessation of activity but only emancipation from ego-illusion, or from mistakenly taking the ego to be real. The duality of the individual and the world is itself illusory. With these teachings, Maharshi returned to the classic formulations of the venerable Shankaracharya (c. 780-820), the leading expositor of advaita in Hindu thinking.==

Mohandas Gandhi: Hinduism’s Preeminent Voice in the Modern Age

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) march in Bhopal

Professor Lal wrote: “Mohandas Gandhi (2 October 1869 - 30 January 1948) doubtless occupies an altogether distinct place in the history of modern Hinduism. He is chiefly honored today not as a savant of Hinduism, but rather as the principal architect of the Indian independence movement and as the most dedicated advocate of nonviolent resistance as a mass movement. While the rest of the world paid homage to him at his assassination as the supreme example of a moral leader in modern times, his political nemesis, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in his condolence message to the Government of India adverted to Gandhi as ‘the great leader of the Hindu community’. Gandhi’s assassin, a Chitpavan Brahmin by the name of Nathuram Godse, on the contrary viewed the Mahatma as a traitor to the Hindu community, and adamantly held forth to the view that his appeasement of Muslims had led to the emasculation of Hindus. Yet, as the assassin’s bullets pierced Gandhi, he is reported to have said, “He Ram! (Oh, God!, a Hindu invocation of the divine). [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

“In Gandhi’s own lifetime, people clamored for his darshan (or gaze, by means of which the observer also becomes blessed) and even claimed that he was an avatar (incarnation) of God. Gandhi was nearly installed into the pantheon of Hindu gods, yet he himself went so far as to say that a person could not believe in God and still be a Hindu. The contours of his Hinduism are thus not easily delineated and his relation to diverse Hindu communities remained a complex one. A Hindu is not required to visit a temple, and Gandhi seldom did so; however, he championed the rights of dalits, or lower caste Hindus, to worship at temples. Similarly, he was emphatically of the view that when venerable Hindu texts seemed to go against one’s conscience, their teachings were to be rejected; and, yet, he frequently described himself as a believer in sanatan dharma, or the idea that Hinduism is an eternal religion. His prayer meetings were models of ecumenism, as passages were read from Hindu, Muslim, and Christian texts. Gandhi is both one of the critical figures in modern Hinduism’s engagement with other faiths and the supreme representative of Hinduism in contemporary inter-faith dialogues. Though he remained profoundly wedded to the Gita, and viewed it is an insurmountable guide to daily living, his veneration for the Sermon on the Mount never diminished. Many Christian missionaries who came into contact with Gandhi, sometimes toying with the idea of attempting to convert him to Christianity, came away with the opinion that they had seldom encountered a better Christian.==

“Gandhi’s precise contributions to the evolution of Hinduism are likely to remain a matter of discussion for some time, but some insight might be gleaned by considering briefly his positions on questions of caste and ahimsa (nonviolence). Not unlike the Buddha, Gandhi was not greatly inclined to indulge in metaphysical speculations, and utopian though he may have been in many respects, he had an extraordinary awareness of the realities on the ground. His opponents among the lower castes, such as the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar, viewed him as an unrepentant supporter of the caste system, but others have argued that no one did as much as Gandhi to unsettle orthodox Hindus with his various campaigns of social reform and his sharp critiques of untouchability as an excrescence upon Hinduism. Gandhi drew upon a wide array of sources -- Vaishnava, Jain, Buddhist, Christian, and secular humanist -- as he came to formulate his ideas of nonviolent resistance (satyagraha), and though countless Hindu texts have argued for the centrality of satya (truth), Gandhian hermeneutics uniquely posits the relationship of satya to ahimsa as an integral part of Hinduism.” ==

Hinduism in Independent India, 1947 to Present

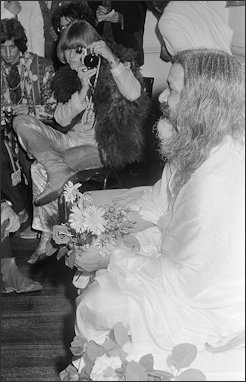

Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones taking a picture of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of Transcendental Meditation

Professor Flood wrote: “The partition of India in 1947, and the resultant bloodshed reinforced nationalistic tendencies and specifically notions of India as 'a Hindu country', and of Hinduism as 'an Indian religion'. These tendencies have continued and, since then, communal violence has frequently erupted. In 1992, Hindus were incited to tear down the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, which they believe was deliberately and provocatively built over the site of Rama's birth. Tensions have been exacerbated by attempts to covert Hindus to other religions and reactions by the continuing hindutva movement. [Source: Professor Gavin Flood, BBC, August 24, 2009 |::|]

“However, the post-war Hindu movements imported into the west, and wide migration of Hindus, raised questions about the exact nature of Hindu identity. From the 1960s onwards, many Indians migrated to Britain and Northern America. Gurus travelled to the West to nurture the fledgling Hindu communities, sometimes starting missionary movements that attracted Western interest. At the end of the millennium, the Hindu communities became well established abroad, excelling socially, economically and academically. They built many magnificent temples, such has the Swaminarayan Temple in London. |::|

“In the late 1960s, Transcendental Meditation achieved worldwide popularity, attracting the attention of celebrities such as the Beatles. Perhaps the most conspicuous was the Hare Krishna movement, whose male followers sported shaved heads and saffron robes. Many such Western adherents, and casual practitioners of yoga also, were attracted to the non-sectarian spiritual aspects of Hinduism. Many Hindu youth in the diaspora have similarly preferred these universal aspects of Hinduism, standing in tension with its more political and sectarian elements. |::|

“Hindus in diaspora were particularly concerned about the perpetuation of their tradition and felt obliged to respond to Hindu youth, who sought a rational basis for practices previously passed down by family custom. They are now particularly concerned about how to deal with contentious issues such as caste, intermarriage and the position of women. In many ways, Hindus in the West are turning back to their roots.” |::|

Modern Hindu Revival

Reporting from Kerala in southeastern India, Rama Lakshmi wrote in in the Washington Post: “In this rapidly modernizing country, new money is also reviving old traditions. A group of mostly urban professionals has teamed up to help conduct the fire ritual this spring in a village that last witnessed it 35 years ago. "We want to do our bit to ensure that Indian culture survives," said Neelakantan Pillai, a banker and member of the newly formed Varthathe Trust, which is organizing the event. "In the new, emerging India, people are ready to open their wallets, write checks for such efforts." [Source: Rama Lakshmi, Washington Post Foreign Service, January 26, 2011]

festival-goers enjoying Rath Yatra Puri

“Across India, wealthy professionals are expressing a newfound pride in the past, and using their money to preserve it. Minor Hindu festivals are now being celebrated in big cities, thanks to corporate sponsorships. The chief of India's largest information-technology company, Infosys, donated more than $5 million to Harvard University for a project on Indian classical literature. Urban Indians are downloading Sanskrit religious verses as cellphone ring tones. Some of the endeavors, analysts say, are building a critical bridge between globalization and God.

“In 2003, the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared the tradition of Vedic chanting a masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity. That distinction has helped raise money and sharpened the focus on preservation efforts. "How did our ancestors preserve this large corpus of Vedic material without written text?" said Sudha Gopalakrishnan, who helped conducted the government's research for the UNESCO proposal. "The chanters acted as human recorders and transmitters. But now, so much has been lost in the last 100 years."

“The tradition faded in modern times, and pious Hindus fear it could die out as young Indians embrace a Western lifestyle and a culture of lavish spending. But many say that India's unbroken oral traditions stand little chance of surviving in the 21st century. "Technology is the only way now. It will soon cease to flow from one generation to the next orally," said Vinod Bhattathiripad, 45, a cyber-crime investigator who created a Web site that documents the practices and scholarship of the Brahmins of Kerala. Bhattathiripad said that his father "looks at my Web site and says, 'I wanted my son to become an engineer to move ahead, not to go back in time.' "

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except the Ayodhya Mosque picture, BBC

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications

Last updated December 2023