HINDUISM

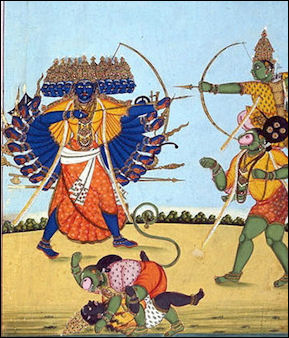

Rama and Hanuman fighting Ravana,

scene from the Ramayana Hinduism is generally regarded as the world's oldest formal religion. Its origins go back to when pastoral Aryan tribes traversed the Hindu Kush from Inner Asia, and mixed with people in urban civilizations in the Indus Valley and tribal cultures in what is now India and Pakistan more than a millennia before Christianity was formed. It is believed that about 1200 B.C., or even earlier by some accounts, the Vedas, a body of hymns originating in northern India were produced; these texts form the theological and philosophical precepts of Hinduism. [Source: Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1991]

Hinduism encompasses an array of deities, including Krishna, Ram, Durga, Kali, and Ganesh. Unlike other world religions, Hinduism had no single founder like Jesus, no one sacred book, like the Quran, but many, and has never been missionary in orientation. Hinduism has no central doctrines; worship can be conducted anywhere; there is no principal spiritual leader, like a pope; and there is no hierarchy of priests analogous to a church. In a sense Hinduism is a synthesis of the religious expression of the people of South Asia and an anonymous expression of their worldview and cosmology, rather than the articulation of a particular creed. The term "Hinduism" applies to a large number of diverse beliefs and practices and is in fact foreign in origin with no easy translation into Indian languages. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992; James Heitzman and Robert Worden, Library of Congress, 1989 *]

Hinduism is a dharma —a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. It is referred to as Sanatana Dharma — the eternal faith — among Hindus in India. Hinduism is not strictly a religion. It is based on the practice of Dharma code of life. Since Hinduism has no founder, anyone who practices Dharma can call himself a Hindu. He can question the authority of any scripture, or even the existence of the Divine.

Hinduism defies easy definition in part because it embraces such a vast array of practices and beliefs. According to the BBC: “Unlike most other religions, Hinduism has no commonly agreed set of teachings. Throughout its extensive history, there have been many key figures teaching different philosophies and writing numerous holy books. For these reasons, writers often refer to Hinduism as 'a way of life' or 'a family of religions' rather than a single religion...Although it is not easy to define Hinduism, we can say that it is rooted in India, most Hindus revere a body of texts as sacred scripture known as the Veda, and most Hindus draw on a common system of values known as dharma... It is also closely associated conceptually and historically with the other Indian religions Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism.” [Source: BBC]

It is important to understand that Hinduism is a cultural way of life. Some practices and beliefs may not be common to all Hindus as regional differences occur. The pluralism evident in Hinduism, as well as its acceptance of the existence of several deities,is often puzzling to non-Hindus. Hindus suggest that one may view the Infinite as a diamond of innumerable facets. One or another facet—be it Rama, Krishna, or Ganesha—may beckon an individual believer with irresistible magnetism. By acknowledging the power of an individual facet and worshipping it, the believer does not thereby deny the existence of many aspects of the Infinite and of varied paths toward the ultimate goal.

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; Vedic Hinduism SW Jamison and M Witzel, Harvard University people.fas.harvard.edu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Advaita Vedanta Hinduism by Sangeetha Menon, International Encyclopedia of Philosophy (one of the non-Theistic school of Hindu philosophy) iep.utm.edu/adv-veda ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ; “India: A History" by John Keay Amazon.com ; "The Wonder That Was India" by A.L. Basham Amazon.com ; ;"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com ; “Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook” translated from the Sanskrit by Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics, 2004) Amazon.com ;“Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization” by Heinrich Zimmer (Princeton University Press, 1992) Amazon.com ;;“Indian Mythology” by Veronica Ions (Peter Bedrick 1984) Amazon.com

Origin of the Word Hindu

Lakshima The words “Hindu” and “Hinduism” have no easy translation in languages spoken in India. In India, a Hindu is simply defined as someone who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jew (or Sikh or Jain). Many Hindus have no name for the religion they follow and have scarcely even heard the word Hindu. The words “Hindu” and “Hinduism” are used primarily by Westerners and non-Indians, though many modern Indians have adopted them. In India, the common name for Hinduism is Sanatana Dharma (“eternal duty of God”). Followers are called Dharmis, which means “followers of Dharma.”

The terms “Hindu” and “Hinduism” originally appear to have had nothing to do with religion. The term refers to the people of the Indus River region of India and Pakistan. “Hindu” is a Persian word derived from Sindhu, the Sanskrit name of the Indus River. Invaders from Persia in the 6th century B.C. named the people of the Indian subcontinent "people living near the Indus River." Ironically the Sindh, the region around the Indus, lies mostly in modern Pakistan, which is almost exclusively Muslim. Hindustan is still the name used by some to describe India. Hinduism wasn’t used to describe South Asia’s dominant religion until the 19th century when Europeans and educated Indians began to use it as such.

As applied to people by early Muslim invaders, Hindu simply meant "Indian." According to Gavin Flood, “Hindu” first occurs as a Persian geographical term for the people who lived beyond the river Indus in the 6th-century B.C. inscription of Darius I (550–486 BCE). Perhaps it was only in the nineteenth century that Europeans and educated Indians began to apply the word specifically to adherents of a particular, dominant South Asian religion.

Among the earliest known records of 'Hindu' with connotations of religion may be in the A.D. 7th-century Chinese text Record of the Western Regions by Xuanzang, and 14th-century Persian text Futuhu's-salatin by 'Abd al-Malik Isami. Some 16–18th century Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava texts mention Hindu and Hindu dharma to distinguish from Muslims without positively defining these terms. In the 18th century, the European merchants and colonists began to refer to the followers of Indian religions collectively as Hindus. The first recorded use of the English term "Hinduism" was by Raja Ram Mohan Roy in 1816–17. By the 1840s, the term "Hinduism" was used by those Indians who opposed British colonialism, and who wanted to distinguish themselves from Muslims and Christians. Before the British began to categorise communities strictly by religion, Indians generally did not define themselves by religion by rather by where they lived, language, varna and jati (castes) , occupation, and sect. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the BBC: “The term 'Hindu' itself probably was used by people to differentiate themselves from followers of other traditions, especially the Muslims (Yavannas), in Kashmir and Bengal. At that time the term may have simply indicated groups united by certain cultural practices such as cremation of the dead and styles of cuisine. The 'ism' was added to 'Hindu' only in the 19th century in the context of British colonialism and missionary activity. “The origins of the term 'hindu' are thus cultural, political and geographical. [Source: BBC]

Definition of the Word Hindu

Today the term Hinduism is widely accepted but because of the wide range of traditions and ideas covered by the term, it is difficult to arrive at a complete, satisfactory definition. It has been said it "defies our desire to define and categorize it". Hinduism has been variously defined as a religion, a religious tradition, a set of religious beliefs, and a "way of life”. From a Western lexical point of view, Hinduism, like other faiths, is appropriately called a religion. In India, the term dharma is preferred, which is broader than the Western term "religion". [Source: Wikipedia]

The definition of Hinduism remains a subject of debate. According to the BBC: In some ways it is true to say that Hinduism is a religion of recent origin yet its roots and formation go back thousands of years. Some claim that one is 'born a Hindu', but there are now many Hindus of non-Indian descent. Others claim that its core feature is belief in an impersonal Supreme, but important strands have long described and worshipped a personal God. Outsiders often criticise Hindus as being polytheistic, but many adherents claim to be monotheists. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Some Hindus define orthodoxy as compliance with the teachings of the Vedic texts (the four Vedas and their supplements). However, still others identify their tradition with 'Sanatana Dharma', the eternal order of conduct that transcends any specific body of sacred literature. Scholars sometimes draw attention to the caste system as a defining feature, but many Hindus view such practices as merely a social phenomenon or an aberration of their original teachings. Nor can we define Hinduism according to belief in concepts such as karma and samsara (reincarnation) because Jains, Sikhs, and Buddhists (in a qualified form) accept this teaching too.” |::|

Difficulty Defining Hinduism

Hinduism encompasses a variety of ideas about spirituality and traditions, but has no religion order, no widely-recognized, agreed-upon authorities, no governing body, no prophets, and no binding holy book; Hindus may choose to be polytheistic, monotheistic, pantheistic, monistic, atheistic, agnostic, or humanistic. According to Mahatma Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu". [Source: Wikipedia]

Ganesh, a popular Hindu god Hinduism often manifests as a belief system with different gods and often different beliefs that go with each god. Most Hindu sects, castes and towns have their special god which they worship somewhat like a patron saint. Typically two things bind Hinduism together: 1) acceptance of sacred Veda scriptures and 2) the caste system. Beliefs in reincarnation and karma are also linked to Hinduism and are also found in Jainism and Buddhism as are other elements of Hinduism. Many Muslims and Christians view Hindus as pagans. A belief in only one God is a cornerstones to Muslim and Christian religions. According to Wendy Doniger, "ideas about all the major issues of faith and lifestyle – vegetarianism, nonviolence, belief in rebirth, even caste – are subjects of debate, not dogma."

Otherwise Hinduism is quite difficult to describe. The religious scholar Jeffrey Parrinder wrote, "Hinduism is a vast subject and an elusive concept...without a defining creed, a group of exclusive adherents or a centralized hierarchy." Another religious scholar A.L. Bashan called Hinduism “a set of beliefs and a way of life” based on “a complex system of faith and practice which has grown up organically in the Indian sub-continent over a period of three millennia.”

In general, the study of India, its cultures and religions, along with the definition of "Hinduism" have been shaped by certain aspect of colonialism and by Western notions of religion. Since the 1990s, these influences and their impact have been the subject of debate among scholars of Hinduism, and have also been embraced by critics of the Western view of India. [Source: Wikipedia]

Characteristics of Hinduism

Hindu followers in different places follow different Hindu gods and practice different teaching associated with one god or a group of gods. Consequently there is no such thing as Hindu orthodoxy and religious beliefs of different Hindu sects varies widely. One thing that has traditionally bound Hindus has been an adherence to the caste system. It has been said that "No [Hindu] is interested in what his neighbor believes, but he is very must interested in knowing whether he can eat with him or take water from his hands." ["The Sacred Writings of the World's Great Religions," Edited by S. E. Frost, McGraw Hill Paperbacks]

Hinduism is not like other formal religions. It is both elaborately ritualist and deeply philosophical but "does not demand adherence to one set of dogmas nor does it prescribe the form of devotion to its myriad gods.” Worship can be conducted anywhere. There are no rules about prayer. Temple attendance and knowledge and study of certain texts are not required. It is possible to follow almost any form of religious practice and still be considered a Hindu. Some Hindus worship Buddha and even Jesus Christ as incarnations of Hindu gods.

Hinduism has been described more as a “way of life” than a “faith” because many of its guiding principals provide instructions on eating, conducting business, farming and taking care of one’s body and are not concerned with salvation and the afterlife. Good Hindus fulfill their responsibilities to their families and their castes and show devotion to gods. There are many variations of Hinduism. The Hinduism practiced in villages is very different from that practiced by religious scholars. The former is often very closely linked to animism and incorporates beliefs in nature spirits and ghosts of ancestors while the latter is more intellectual and philosophical.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Despite the great diversity in forms of Hindu worship, the hundreds of diverse sects, and the vast number of deities worshiped (conventionally 330 million), there are certain philosophical principles that are generally acknowledged by Hindus. In brief, there are four aims of living and four stages of life. The aims of living (and their Sanskrit-derived names) are: (1) artha, material prosperity; (2) kama , satisfaction of desires; (3) dharma, performing the duties of one's station in life; and (4) moksha, obtaining release from the cycle of rebirths to which every soul is subject. These aims are thought to apply to everybody, from Brahman to Untouchable. So too are the four stages of life, which are studentship, becoming a householder, retiring to the forest to meditate, and finally, becoming a mendicant ( sannyasi ). [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 3: South Asia,” edited by Paul Hockings, 1992 |~|]

Diversity and Unity in Hinduism

Hinduism embraces a vast and varied body of religious belief, practice, and organization. In its widest sense, Hinduism encompasses all the religious and cultural systems originating in South Asia, and many Hindus actually accept the Buddha as an important sectarian teacher or as a rebel against or reformer of ancient Hindu culture. Hindu beliefs and practices in different regions claim descent from common textual sources, while retaining their regional individuality.[Source: Russell R. Ross and Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1988]

Because Hindu beliefs are so vast and diverse, Hinduism is often referred to as a family of religions rather than a single religion. Within each religion in this family of religions, there are different theologies, practices, and sacred texts. Hinduism does not have a "unified system of belief encoded in a declaration of faith or a creed". According to the Supreme Court of India, Unlike other religions in the World, the Hindu religion does not claim any one Prophet, it does not worship any one God, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one act of religious rites or performances; in fact, it does not satisfy the traditional features of a religion or creed. It is a way of life and nothing more". [Source: Wikipedia]

Despite their differences, there is also a sense of unity among most Hindu traditions. The Vedas, a body of religious or sacred literature, are revered by many Hindus as a reminder of their ancient cultural heritage and a source of pride. Even so, the respected French Indologist Louis Renou pointed out that "even in the most orthodox domains, the reverence to the Vedas has come to be a simple raising of the hat". The German-born Indologist and philosopher Wilhelm Halbfass said that although different Hindu denomination Shaivism and Vaishnavism may be regarded as "self-contained religious constellations", there is a degree of interaction and reference between the "theoreticians and literary representatives" of each tradition that indicates the presence of "a wider sense of identity, a sense of coherence in a shared context and of inclusion in a common framework and horizon".

Sacred Hindu Texts

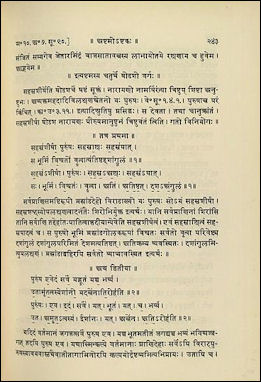

Rig Veda page Hinduism have many sacred documents but no single sacred text such as the Bible. "The result," writes historian Daniel Boorstin, is "a wonderfully varied and constantly enriching Hindu jingle-jangle of truths, but no one path to The Truth." Hindu texts are so closely associated with Sanskrit that all translations are regarded as profanation.

There are five primary sacred texts of Hinduism, each associated with a stage of Hinduism’s evolution. They are: 1) the “Verdic Verses” , written in Sanskrit between 1500 to 900 B.C.; 2) the “Upanishads” , written 800 and 600 B.C.; 3) the “Laws of Manu”, written around 250 B.C.; and 4) “Ramayana” and 5) the “Mahabharata”, written sometime between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200 when Hinduism was popularized for the masses.

Hindu cosmology was explained in the Vedas. The Upanishads provided a theoretical basis for this cosmology. The “Brahmanas” , a supplement to the Vedas, offers detailed instructions for rituals and explanations of the duties of priests. It gave form to abstract principals offered up in the earlier texts. Sutras are additional supplements that explain laws and ceremonies.

The Hindu sacred texts are divided into Shruti (“What Is Heard”) and Smriti (“What Is Remembered”). The Sruti — which includes the Vedas and Upanishads — are considered to be divinely inspired while the Smriti — which includes the Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita) and Ramayana — are derived from great sages. Some sources include a third category: nyaya (meaning 'logic'). Hindu Shruti-Smriti classifications are based on origin not on the mode of transmission. Therefore, shruti implies something heard directly from the Gods by the sages while smriti refers to what was written down and remembered. Shruti is considered more authoritative than smriti because the former is believed to have been obtained directly from God by the spiritual experiences of vedic seers and has no interpretations.

See Separate Article: HINDU TEXTS: THE VEDAS, UPANISHADS, BHAGAVAD GITA AND RAMAYANA factsanddetails.com

Hindu Organization and Authority

Hinduism is not strictly a religion. It is based on the practice of Dharma, the code of life. Since Hinduism has no founder, anyone who practices Dharma can call himself a Hindu. He can question the authority of any scripture, or even the existence of the Divine.

Christianity is an organized religion with a hierarchy that emphasizes community worship and social service. Eastern religion is not organized in the same way. Hindus have special religious communities but the religion itself is not organized and worship has traditionally been done individually rather than in groups. Even when there are gathering of large numbers of people, individuals tend to engage in worship as individuals.

Authority and eternal truths play an important role in Hinduism. Religious traditions and truths are believed to be contained in its sacred texts, which are accessed and taught by sages, gurus, saints or avatars. [Source: Wikipedia]

However, Hinduism also has a strong tradition of questioning authority, engaging in internal debates, and challenging religious texts. This is believed to deepen the understanding of eternal truths and further develop the tradition. Authority was mediated through an intellectual culture that tended to develop ideas collaboratively, based on the shared logic of natural reason. Narratives in the Upanishads present characters questioning persons of authority. The Kena Upanishad repeatedly poses the question 'by what' power something is the case. The Katha Upanishad and Bhagavad Gita present narratives in which the student criticizes the teacher's inferior answers. In the Shiva Purana, Shiva questions Vishnu and Brahma. Doubt plays a recurring role in the Mahabharata. Jayadeva's Gita Govinda presents criticism through Radha.

Hindu Worship

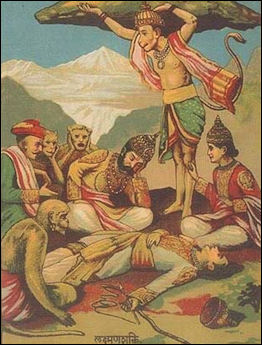

Hanuman, Fall of Laxmanai Hindus and Buddhists are not required to visit temples. There is generally no liturgy or community worship for a congregation at a temple. The largest gathering usually take place at festivals, when some public ceremonies are held. Otherwise temples are mostly empty of people unless they are tourist attractions or are very popular. As a rule individuals come and go to temples when they please and worship on a one on one basis with the god they are praying to. Temples are often sought as quiet places for meditation. Worship can often be done in front of altars at home just as well as it can be done at a temple. Reverence toward sacred images is very important. Sacred images are treated as kings in their temples and honored guest in people’s homes. This reverence is an expression of “darshan” . Common prayer times are sunrise and sunset when priests conduct ritual offering to the icon in the sanctuary of the temple.

The religious scholar A.L. Basham, wrote: “The most important religious acts of the Hindu are performed within the home. The life of the individual is hedged with sacraments of all kinds, which accompany him not merely from cradle to grave, but even from conception to long after death; for rites are performed while an unborn child is still in the womb to ensue its safety; and an ancestor is cared for in the after-life by special ceremonies performed by his descendants.”

At certain times of the day family members make offerings and say prayers at the family altar. Sometimes they say their prayers together, with the head of the household leading. Other times they do them at separate times. The lighting of a lamp and incense is a usual part of the ritual. Sweets, coconut, money and fruit are left as offerings. Prayers are usually said every day. Thursday is regarded as a particularly auspicious time to say them.

See Temples.

Hindu Beliefs

Hindus believe in four “purushartha” (aims of the living, or instrumental and ultimate goals): 1) “artha” (material prosperity); 2) “kama” (satisfaction of legitimate desires); 3) “dharma” (moral conduct and duties associated with one’s station in life); and 4) “moksha” (obtaining release from the cycle of deaths and rebirths). These aims are thought to apply to everyone, regardless of caste, from Brahmin to Untouchables.

According to the “advaita” philosophy the world and everything in it is an illusion and is one. There is only one divine principle in Hinduism and all the different gods are manifestations of this cosmic unity. Hindus often say, "We believe God is everywhere...We believe God is you, too." The only essential truth and desire is the one that is possessed within. Other things found in life are generally distortions and untruths. Many Hindus view life, existence and cosmology as too complicated to be followed as a simple creed. It is therefore up to an individual or group to pick the aspects of the religion that they feel applies to them.

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “From its beginnings, Hinduism has possessed a remarkable ability to assimilate rather than reject new ideas. It has developed complex overlays of beliefs, cults, gods, and forms of worship. Hindu's great texts were not inscribed but handed down as an oral tradition. Hindu worship is based on a one-to-one relationship between devotee and god rather than being congregational. This practice intensified beginning in the seventh century with the popularity of bhakti, passionate personal devotion to an individual god or goddess. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

See Separate Article BASIC HINDU BELIEFS: factsanddetails.com

Hinduism, Reincarnation and Transmigration

Gandhi cremation Reincarnation is the transmigration of the soul from one life form to another. It doesn’t just apply to humans but to all creatures and some non-living things too. Transmigration of the soul can take place from a human or creature into another human or creature up or down a scale based on good and evil deeds (See Karma Below). If a person has lived a virtuous life he moves up the scale, say, from a low caste to a high caste. If a person has lived an unworthy life he moves down the scale, say, from a low caste to a rat.

Reincarnation is a belief found in most Asian religions and is a cornerstone of all the major religions found in India except Islam. The Hindu idea of reincarnation is roughly the same regardless of which Hindu god an individual venerates most.

The Hindu concept of reincarnation first appeared in the Upanishads and is believed to have originated in the Ganges Plain and was absorbed b the Aryan-centered Hinduism as the Aryans moved into the Ganges Plain. Beliefs in reincarnation are not just found in India and Asia but are found in tribal cultures all over the world and were held by the ancient Greeks, Vikings and other groups in the West. Ideas about reincarnation are probably very old and were held by people who lived in Neolithic times.

See Separate Article: factsanddetails.com

Hindu Gods

According to Hindu scriptures there are 330 million “devas” (Hindu Gods). These gods come in many forms and types. Some well-known ones are featured in well-known Hindu myths. Some local ones are worshiped in only a few villages or even by a few villagers. Some are associated with animals, plants (all living things are regarded as divine) as well as natural objects and forces. Others are deified ancestors or historical figures. Many deities are associated with particular places or specialized powers or seasons. The pantheon of gods is as complex as it is vast. Identifying which god is which is often very difficult because they are usually depicted as eternally young and have the same serene expressions. Identification is often made from certain features or certain object they are holding or the animal they are riding on. Making matters even more complex is the fact that the names of gods, their stories, ancestry and links with other god often varies quite a bit from place to place. Many gods have been created over the years through the amalgamation of different gods and cults.

Individual Hindus generally recognize a multiplicity of gods but are only devoted to one or a few of them. In Hinduism there is no real hierarchy of gods. Each god and goddess in Hinduism occupies its own heaven and is worshiped with a different set of doctrines and beliefs. Each gets its turn receiving “darśan” from Hindu followers.

Many Hindu rituals are oriented towards specific deities. Most of the practices are based on sacred treatises of relatively recent origin. Devout Hindus invoke the names of deities at the beginning of business and religious ceremonies. After winning a big case some Hindu lawyers thank the mother goddess Kali with a sacrificed goat.

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Today the great majority of Indian people are Hindus. Although Hindus may select one deity for personal worship among the great gods and goddesses and the countless regional and local gods, all of these deities can be under- stood as representing the many aspects of the One.” [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Hinduism and the West

Many Westerners travel to India to seek enlightenment. They take part in pilgrimages; live in ashrams; take yoga and meditation classes; receive ayuvedic treatments; and study with gurus. The trend began in the 1960s, with The Beatles among those who participated, and is currently experiencing a revisal with 50 ashrams that cater to Westerners in the holy town of Rishikesh alone. Today travelers are not just hippies but people of all ages from a wide spectrum of society. Interestingly, some of the spiritual center set up for Westerners have become increasingly fashionable among Indians as well.

Hindu nationalists have issued death threats to American academics for having controversial theories about Hindu gods. Emory University’s Paul Courtright, for example, angered such people by suggesting that the god Ganesha might symbolize a limp penis. He became the target of an Internet campaign in which participants said things like “The professor should be hanged” and “wish this person was next to me. I would shoot him dead.” An aide for a professor who wrote a book about the 17th century Hindutva hero Shivaji was attacked by the group of Hindu nationalist thugs Shin Sheva.

Madonna appeared as Shiva at the 1998 MTV awards. The World Vaishnava Association were upset by her suggestive dancing while wearing make-up that represented purity and devotion. Madonna did a Hindu yoga chant (Shanti/ Ashtangi) on her album “Ray of Light.”

Hinduism and Other Religions

Because many Hindus believe in a Supreme Being that manifests itself in different forms and at different times, they accept other religious paths as true and valid. Some Hindus seek the blessing of Muslim holy men at Sufi shrines. But Hindus generally do not proselytize. Notable exceptions to this rule include the Ramakrishna Mission and the Hare Krishna movement. Some, but not all, Hindu sects accept converts. [Source: Leona Anderson, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Hindus are not required to visit temples and Christians and Muslims are with churches and mosques. Hindus have special religious communities but the religion itself is not organized. Buddhism has monasteries for those who have decided to devote themselves entirely to the religion but no communal place for lay people to worship. Temples attract large crowds during festivals and they are often sought as a quiet place for meditation but worship and initiation rites are often performed in front of an altar at home.

Some Hindus accept Jesus as an avatar, or incarnation, of God. Of these some consider Jesus to be a self-realized saint who has reached the highest level of God consciousness.” There are some stories that Jesus traveled to South Asia when he was a teenager to study meditation and returned to Palestine to be a guru for the Jews. The idea of the halo did not originate with Christianity. Gods and spirits in ancient Hindu, Indian, Greek and Roman art sometimes had light radiating from their heads.

Many Hindus believe that Sikhism, Buddhism, and Jainism are different forms of Hinduism, though Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains do not necessarily agree. Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, is regarded as the ninth avatar of Vishnu. Some Hindus identify Christ as the tenth avatar; others regard Kalki as the final avatar who is yet to come. These avatars are believed to descend upon earth to restore peace, order, and justice, or to save humanity from injustice. The Mahabharata (compiled by the sage Vyasa, probably before 400), describes the great civil war between the Pandavas (the good) and the Kauravas (the bad) — two factions of the same clan. It is believed that the war was created by Krishna. Perhaps the flashiest and craftiest avatar of Vishnu, Krishna, as a part of his lila (sport or act), is believed motivated to restore justice — the good over the bad. [Source: Andrea Matles Savada, Library of Congress, 1991]

Future of Hinduism

Professor Lal wrote: “Contemporary Hinduism is too diverse, polyphonic, and multi-layered to be encapsulated through only its stellar figures, institutional histories, and the meta narratives which dwell on pan-Indian deities or the familiar sectarian histories of Vaishnavism and Saivism. The worship of minor deities persists, and moreover gods and goddesses die, take birth, or witness some rejuvenation. It will suffice to draw attention to a few of the more arresting developments of recent times. First, both abroad and even among the more affluent classes in India, Hinduism is increasingly being understood through such allied phenomena as yoga, ayurveda, vegetarianism, and even vastu shastra, the science which purports to establish how architecture and building structures could be propitious to human well-being. It is not clear, for instance, whether Jawaharlal Nehru had any propensity towards Hindu beliefs, but he was a keen advocate of yoga. For some Hindus, it is no exaggeration to say, vegetarianism is their dharma, the moral law of their being. To the Hindus in the United States who successfully filed a class-action lawsuit against McDonald’s for using beef fat in the preparation of allegedly “vegetarian” french fires, vegetarianism, and in particular the complete disavowal of beef products, was the most explicit manifestation of their Hinduism. Certainly contemporary accounts of Hinduism can ill-afford to ignore these phenomena. [Source: Vinay Lal, “Hinduism” in “Encyclopedia of the Modern World,” ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), Vol IV, pp. 10-16. ==]

“Secondly, Hinduism is now present world-wide, even though the vast bulk of its practitioners reside in the Indian sub-continent. Diasporic Hinduism takes many forms, and an even more arresting question is whether it simply mimics Hinduism in India, or if it sometimes generates new Hindu practices and even helps to determine Hinduism’s contours in the land of its birth. The nearly 2-million strong affluent Hindu community in the United States is opting for opulent, indeed ostentatious, temples the construction of which is increasingly being handed over to architects and craftsmen imported from India. Hindu communities seem eager to embrace what they view as the most ‘authentic’ forms of Hinduism. Scholars of Hindu nationalism have noted that Hindu militancy in India receives considerable support from Hindus settled in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and disputes and controversies originating in India often get replayed in the diaspora. The agitation among certain Hindus over the content, regarding Hinduism and ancient India, of sixth-grade world history textbooks in California is a case in point as nearly the same controversies had previously broken out in India. On the other hand, Hinduism has displayed a characteristic versatility in the diaspora. The comparatively minor village deity sometimes encountered in Tamil Nadu, Munisvaran, has been raised to the status of a major god among Malaysian Hindus, and everywhere, from Southeast Asia to Fiji, Mauritius, and Australia, the Tamil diaspora has been successful in transforming the worship of the god Murugan into a major public festival. Using the traditional form of popular Hindu literature called the Puranas as a model, the Indo-Fijian writer, Subramani, published the first Purana ever written in Bhojpuri. It is important to recognize that an overwhelmingly Muslim country such as Indonesia continues to derive much cultural sustenance from Hindu epics and mythological stories.==

“Thirdly, Hinduism is, like most other phenomena of our times, a part of the cinematic, television, and digital age. A genre of films called ‘mythologicals’ made popular Hindu narratives from the 1930s onwards, and the film Jai Santoshi Maa (1975) won the goddess many new converts. Santoshi Mother’s ritual fast (vrat) over sixteen consecutive Fridays began to be observed by millions. The observance by the unmarried heroine in the film Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) of another fast, the Karwa Chauth, customarily kept by married Hindu women, apparently instigated many young girls to emulate the film’s heroine. Ramanand Sagar’s epic TV serials, Ramayana (1986-88) and Krishna (1989) brought the Puranic literature to television screens, and B. R. Chopra followed with the mega-serial, Mahabharata (1988-90), relayed on successive Sunday mornings over two years. This seems unobjectionable enough, but some scholars have argued that the television Ramayana homogenizes the Ramkatha (story of Rama), elevating the conservative version of Tulsidas over competing versions. Hinduism has now entered cyberspace, appropriately enough for a religion that, like the world wide web, is extraordinarily decentered, polymorphous, and comparatively lacking in doctrinal authority. New Hindu histories, which are not very attentive either to Hinduism or to the protocols of historical scholarship, are constantly being generated on the web. One website features the “Hindu Holocaust Museum” to document what is alleged to be the murder of millions of Hindus by Muslim invaders over the last millennium. Strangely, some websites on Hinduism not only give an overview of the faith, but also document Islamic terrorism, a decisive sign that Islam is critical to Hindutva’s self-identity.==

“As one contemplates the future of Hinduism, one is also struck by the fact that modernizing Hindus, while eager to project Hinduism as a uniquely tolerant and ancient faith that has been fed by diverse strands, are ironically also tempted to bring Hinduism into conformity with the major semitic faiths. They resent, for example, the description of Hinduism as a polytheistic faith and are keen that Hindus should be viewed as monotheists. They are animated by a feverish sense of history and adamant in suggesting that Hinduism’s truths are compatible with the findings of modern science. The ideologues of Hindutva and their supporters who demolished the Babri Masjid are historical-minded to the extent that they have, unlike Hindus of the past, historicized Hindu deities. The tendency to scientize Hinduism is most palpably on display both in the argument, encountered frequently among Hindu nationalists, that the Vedas are repositories of scientific truths that are now only now being discovered by the scientific community, and in the worldwide dissemination of ‘scientific Hinduism’ by the (many wealthy) Gujarati adherents of Swaminarayan Hinduism. Their extraordinary opulent structures, in London, Delhi, and Bartlett (outside Chicago) are not so much temples as museums of Hinduism. If one accepts that Hinduism is largely a religion of mythos, a religion without a historical founder or a central text, and perfectly at ease with its own indifference to history as a category of knowledge, then there is no question that the attempted transformation of Hinduism into a religion of history among some of its advocates will be one of the most contested elements in its continuing evolution as a faith responsive to one-eighth of humanity.==

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger

Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones taking a picture of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of Transcendental Meditation

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger is a massive book and study of Hindusim that is better suited for people that want an in depth look at Hinduism rather than a more lightweight introduction. The book also said some things that Hindus and politicians in India didn't like and was banned there (See Below). Doniger is an eminent Sanskrit scholar at the University of Chicago, author of many books about cultural, religious and folkloric beliefs, and a translator of several Indian classics, including "The Rig Veda" and "The Kamas Sutra." Her annotations to the latter, the famed sex manual, its has been said are as "entertaining and informative as the book itself. [Source: Michael Dirda, Washington Post, March 19, 2009]

In a review of "The Hindus", Michael Dirda wrote in the Washington Post, “While Doniger does trace the evolution of Hinduism from the time of the Indus Valley Civilization (2,500 B.C.) to the present, she deliberately emphasizes a small number of recurrent threads, in particular the ways that "women, lower classes and castes, and animals" have endured or surmounted their traditional status. Horses, for instance, are typically glamorous, cows sacred and dogs despised — but not always...Having been trained as a philologist, Doniger organizes her history around interpretations of the most revered classics of Sanskrit poetry and philosophy. She begins with the Rig Veda, a collection of hymns to the Zeus-like Indra and other ancient gods. This is a work so sacred that manuscripts display no textual differences: To alter a word was unthinkable. She also examines women, castes and animals in the Upanishads — essentially, meditations on the meaning of the Vedic rituals and myths — and the 2,000-year-old Indian epics "The Ramayana" and "The Mahabharata."

“Consider, for instance, the portrait of Sita in "The Ramayana." In this long poem, the beautiful Sita is kidnapped by an ogre but eventually rescued by her husband, Rama. Unfortunately, after the initial happiness of their reunion, Rama starts to wonder about his wife's chastity during her long imprisonment. Would she not have succumbed or been forced to submit to the lecherous ogre's embrace? Although Sita proves and proves again her innocence, Doniger underscores the crassness of Rama's jealous-husband behavior but also notes certain textual hints that Sita is more sexual than she appears and that her feelings for Rama's brother Lakshmana might well be more than familial. As Sita is the classic model of Indian womanhood, such sacrilegious speculation once led to Doniger being egged at a London lecture.

student at a Veda school

“"The Mahabharata" is an immensely long poem — seven times the combined length of the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey" — that relates the history of the five Pandava brothers (who are all married to the same woman, Draupadi — Doniger expresses regret that she, rather than Sita, didn't provide the template for Indian womanhood). The Pandavas eventually go to war against their cousins, the 100 sons of Dhritarashtra, and the poem climaxes in a great battle. But just before the two armies clash, the formidable warrior Arjuna suddenly recoils from the coming slaughter, overwhelmed by horror and sorrow. In a still moment outside of time, he begins to discuss the meaning of life with his charioteer, the god Krishna in human form. This section of the epic is often read separately, being one of the supreme masterpieces of spiritual literature: the "Bhagavad-Gita," or "Song of the Blessed One." In the end, Krishna persuades Arjuna to let go of personal desire, unite his will to that of God and perform his sacred duty (dharma) in a spirit of acceptance and detachment, without thought of either success or failure.

“Doniger also tells another story from "The Mahabharata," one in which the five Pandavas are all trying to reach heaven and each drops away, until only Yudhishthira continues on the straight and narrow path, alone except for a stray dog that follows him. At the story's climax, Indra appears to this most virtuous Indian brother and, praising him, requests that he step into his celestial chariot and be transported to heaven — just as soon as he gets rid of that mangy dog. In the words of the old Christian hymn, "once to every man and nation, comes the moment to decide," and Yudhishthira refuses to abandon this animal who has been so loyal to him. At which point the dog reveals himself to be Dharma, the god of right behavior: "Great king . . . Because you turned down the celestial chariot, by insisting, 'This dog is devoted to me,' there is no one your equal in heaven." Since dogs were traditionally unclean, Doniger notes of this story that "it is as if the god of the Hebrew Bible had become incarnate in a pig." This is characteristic of her cheeky tone, given to jokes and wordplay: According to Doniger, when Sita glimpses a golden deer encrusted with jewels, she is "delighted to find that Tiffany's has a branch in the forest." Such humor — sometimes charming, as here — reflects that strange desire of modern academics to be viewed not only as learned but also as hip and funky.

“While deconstructing her various Indian texts, Doniger duly explores such concepts as karma ("action, or the fruits of action"); ahimsa (nonviolence); bhakti ("passionate devotion to a god"); samsara (the circle of transmigration of souls); and the caste system, consisting of Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors and kings), Vaishyas (merchants) and Shudras (servants), as well as that fifth class, the Dalits, or so-called Untouchables. Just learning Sanskrit words like moksha (release) is an education in itself.

RSS volunteers helping out after the 2004 tsunami

“Doniger's last chapters are the most historical and by far the easiest. She traces the impact of the British on Indian culture and writes movingly about Kipling's "Kim," that great-hearted novel packed with colonialist attitudes yet full of the utmost sympathy and love for India and its people. She discusses Orientalism, Gandhi, right-wing Indian political groups and Bollywood, before finishing her story by touching on the reception and distortion — Tantric sex! — of Hindu culture in the West. Wendy Doniger's erudite "alternative history" shouldn't be anyone's introduction to Hinduism. But once you've learned the basics about this most spiritual of cultures, don't miss this equivalent of a brilliant graduate course from a feisty and exhilarating teacher.”

Book: “The Hindus: An Alternative History” by Wendy Doniger, Penguin Press,, 2009. Doniger is a University of Chicago professor.

Wendy Doniger’s Book Withdrawn from Publication in India

In February 2104, Penguin India, an arm of US-based publisher Penguin Random House, announced it was going to stop publication of “The Hindus: An Alternative History” by Wendy Doniger and estroy existing copies of the book, after rightwing Hindu activists complained that it denigrated their religion. Amy Kazmin wrote in the Financial Times, “Confronted with several criminal complaints and a civil lawsuit, Penguin India agreed to destroy all unsold copies of... the critically acclaimed book. As part of the out-of-court settlement, India’s Shiksha Bachao Andolan – or Save Education Movement, a conservative Hindu activist group which sued Penguin in 2011 over the book – has agreed to withdraw its lawsuit and criminal complaints against Penguin and Ms Doniger. [Source: Amy Kazmin, Financial Times, February 12, 2014 |~|]

“In a statement, Ms Doniger said she was “angry and disappointed” at the events, and “deeply troubled about what it foretells for free speech in India in the present, and steadily worsening, political climate”. She said she did not “blame” Penguin, which published the book “knowing it would stir anger in the Hindutva ranks” and defended it legally for four years. She said Penguin was “finally defeated by the true villain of the piece – Indian law, which makes it a criminal rather than civil offence to publish a book that offends any Hindu, a law that jeopardises the physical safety of any publisher, no matter how ludicrous the accusation”. Her works would remain available in India electronically.

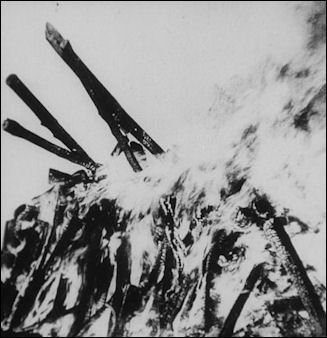

Christian girl burned after Hindu nationalists threw a firebomb into her family's home

“Penguin India’s decision to destroy all copies of a 692-page academic tome on ancient Hindu mythology by a leading Sanskrit scholar has caused a storm, with some Indians accusing the publisher of capitulating on critical principles of free speech and academic freedom. “It was very unwise for Penguin to agree to this,” said Swapan Dasgupta, a political commentator. “When publishers get intimidated and cowed down by fringe groups, rather than stand up to scrutiny, then it’s very dangerous. It opens the floodgates for all sorts of little fringe groups.” India ostensibly protects free speech, and is known for its vigorous political debate. But it also has highly elastic laws against inciting hatred, or “hurting the sentiments” of religious communities, which conservatives from across the religious spectrum have successfully used to suppress creative works not to their tastes, such as paintings of Hindu deities by the late artist M.F. Husain. “The political economy of hurt sentiment has been extremely well-played by the religious right,” Mr Liang said. “Every religious community knows how to play this game. But publishers have to be willing to take this fight on.” |~|

“Ms Doniger has written 16 books, including modern translations of Sanskrit literature with annotations and commentary. However, her “joyful, sexual, pagan account of Hinduism,” as Mr Liang describes it, has made her the bête noire of rightwing Hindu groups, which embrace more puritanical aspects of their faith. Hindu critics claimed The Hindus contained errors and that Ms Doniger’s use of Freudian psychoanalytical tools to analyse ancient myths was disrespectful to Hindu deities. The settlement comes as India gears up for parliamentary elections, which India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party is widely expected to win.” |~|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); . National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications

Last updated December 2023