ATMAN — THE HINDU IDEA OF THE SOUL

The Upanishads, originating as commentaries on the Vedas between about 800 and 200 B.C., contain speculations on the meaning of existence that have greatly influenced Indian religious traditions. Most important is the concept of atman (the human soul), which is an individual manifestation of brahman . [Source: Library of Congress]

Atman is of the same nature as brahman , characterized either as an impersonal force or as God, and has as its goal the recognition of identity with brahman . This fusion is not possible, however, as long as the individual remains bound to the world of the flesh and desires. In fact, the deathless atman that is so bound will not join with brahman after the death of the body but will experience continuous rebirth. This fundamental concept of the transmigration of atman , or reincarnation after death, lies at the heart of the religions emerging from India.

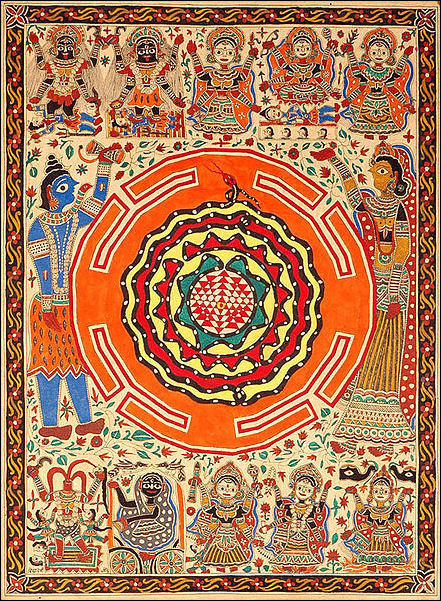

“Atman” is seen as a kernel that lies at the center of a large onion and is only revealed after the layers around it — associated with the body, passions and mental powers — are removed in a step by step fashion. The true goal of atman is liberation, or release (moksha, See Below), from the limited world of experience and realization of oneness with God or the cosmos. The Taittiriya Upanishad defines five layers or sheaths (from the outer to the kernel): 1) the body 2) bio-energy, the equivalent of Chinese qi; 3) mental energy; 4) intuition and wisdom; 5) pure bliss achieved mainly through meditation. These layers can be removed through self actualization and the kernel of eternal bliss can ultimately be realized.

Hindus believe in “Paramatman” (the eternal, blissful self), which contradicts the Buddhist belief in the impermanent and transitory nature of things. Gavin Flood, a professor of Theology at Oxford, wrote in a BBC article: “Atman means 'eternal self'. The atman refers to the real self beyond ego or false self. It is often referred to as 'spirit' or 'soul' and indicates our true self or essence which underlies our existence. There are many interesting perspectives on the self in Hinduism ranging from the self as eternal servant of God to the self as being identified with God. The understanding of the self as eternal supports the idea of reincarnation in that the same eternal being can inhabit temporary bodies. “The idea of atman entails the idea of the self as a spiritual rather than material being and thus there is a strong dimension of Hinduism which emphasises detachment from the material world and promotes practices such as asceticism. Thus it could be said that in this world, a spiritual being, the atman, has a human experience rather than a human being having a spiritual experience.” [Source: Professor Gavin Flood, BBC, August 24, 2009 |::|]

Websites and Resources on Hinduism: Hinduism Today hinduismtoday.com ; India Divine indiadivine.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Oxford center of Hindu Studies ochs.org.uk ; Hindu Website hinduwebsite.com/hinduindex ; Hindu Gallery hindugallery.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica Online article britannica.com ; International Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/hindu ; The Hindu Religion, Swami Vivekananda (1894), .wikisource.org ; Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press academic.oup.com/jhs

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"An Introduction to Hinduism" by Gavin Flood Amazon.com ;

“Hinduism for Beginners - The Ultimate Guide to Hindu Gods, Hindu Beliefs, Hindu Rituals and Hindu Religion” by Cassie Coleman Amazon.com ;

“Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook” translated from the Sanskrit by Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics, 2004) Amazon.com ;

“India: A History" by John Keay Amazon.com ;

“The Rig Veda” by Anonymous and Wendy Doniger (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

"The Hindus: An Alternative History" by Wendy Doniger; Amazon.com ;

“The Upanishads” by Anonymous and Juan Mascaro (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“The Bhagavad Gita” by Anonymous and Laurie L. Patton (Penguin Classics)

Amazon.com ;

“Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization” by Heinrich Zimmer (Princeton University Press, 1992) Amazon.com

Hindu Views on What Happens to the Soul After Death

Because of the belief in Hinduism that the Atman is eternal and the concept of Purusha (the cosmic self or cosmic consciousness), death can be seen as insignificant in comparison to the eternal Atman or Purusha. Purusha is a complex concept whose meaning evolved in Vedic and Upanishadic times. Depending on the source and historical timeline, it means the Cosmic Being or Self, Consciousness, and Universal Principle. [Source: Wikipedia].

At death the sheaths break apart one by one, and go their separate ways revealing the atman, which departs the body and goes on a path defined by an individual’s karma. In most cases the individual goes to a niche in the cosmos occupied by his ancestors or to one of the 21 heavens and hells of Hindu cosmology and remains there for duration defined by their karma until he or she is ready to be reborn.

There is little mourning when a Hindu dies because they believe that once a person is born he or she never dies. Krishna said in the Bhagavad-Gita that "Worn-out garments are shed by the body: worn-out bodies are shed by the dweller within...New bodies are donned by the dweller, like garments.” Death is often viewed in a positive light: as an escape from one life on the road to a better an ultimate moksha (nirvana), shanti (peace) and paramapada (the ultimate place).

On the subject of death one passage in the Rig Veda reads:

“When he goes on the path that lead away the breath of life.

Then he will be led by the will of the gods

May your eye go to the sun, you life’s breath to the wind

Go to the sky or the earth, as is your nature. “

The Vedas refer to two paths taken after death: 1) the path of the ancestors, where the deceased travels to a heaven occupied by ancestors and is ultimately reborn; 2) the path of gods, where the deceased enters a realm at the sun and never returns. The latter is the equivalent of reaching nirvana and escaping reincarnation. There is also a reference to a hell-like “pit” where sinners are punished.

Moksha

“Moksha” is the Hindu equivalent of “nirvana” . It means “release” or “liberation” and refers to the release from the cycle of deaths and rebirths and merging of the personal self with the cosmic self. In the Vedas, there are references to sages experiencing eternal bliss but little is said on how they achieved it or what it was like. The “Upanishads” describes the path to moksha as a quest “from the unreal....to the real; from the darkness...to light; from death...to immorality.” One who attains moksha is called a “jivam-mukta”, or freed soul. After death “he goes to light [traveling] from the sun to the moon from the moon to lightning...This is the path of the gods...Those that proceed on this path do not return to the life.”

Moksha is the ultimate, most important goal in Hinduism. It associated with liberation from sorrow, suffering, and for many theistic schools of Hinduism, liberation from samsara (the birth-rebirth cycle). The idea of release from suffering and liberation from the birth-rebirth cycle are also important in Buddhism as is nirvana which many view as the same as or similar to moksha. The idea of Buddhist nirvana grew out of the Hindu idea moksha.

Moksha is something that has to occur in natural rather than deliberate way. It can only be attained when all desire and attachment, including the desire for moksha have been overcome. Descriptions of it tend to be focused more on achieving it than what it is like.

The Bhagavad Gita reads: “The man who has reached perfection attains the Supreme Being, which is the end, the aim, and the highest condition of spiritual knowledge...Imbued with pure discrimination, restraining himself with resolution, having rejected the charms of sound and other objects of the senses, and casting off attachment and dislike; dwelling in secluded places, eating little, with speech, body and mind controlled, engaging in constant meditation and unwaveringly fixed in dispassion, abandoning egotism, arrogance, violence, vanity, desire, anger, pride, and possession, with calmness, ever present, a man is fitted to be the Supreme Being. And having thus attained the Supreme Being, he is serving sorrow no more, and no more desiring but alike towards all creatures he attains to supreme devotion.”

Differing Views on Moksha Within Hinduism

The concept of moksha varies among different schools of Hindu thought. In theistic schools, it is commonly viewed as liberation from samsara, while in other schools, such as the monistic school, it is considered a psychological concept that can be achieved during one's lifetime. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to Advaita Vedanta, upon attaining moksha, an individual realizes their essence or self to be pure consciousness, also known as witness-consciousness, and identifies it as identical to Brahman. Followers of Dvaita (dualistic) schools believe that in the afterlife moksha state, individual essences are distinct from Brahman but infinitesimally close. After attaining moksha, they expect to spend eternity in a loka (heaven). The Vedantic school distinguishes between two views on the nature of moksha: Jivanmukti, which refers to liberation in this life, and Videhamukti, which refers to liberation after death.

The scholar Eliot Deutsch defines moksha as a state of transcendental consciousness, self-realization, freedom, and the realization of the universe as the Self. Klaus Klostermaier argues that, as a psychological concept, moksha implies the liberation of previously fettered faculties and the removal of obstacles to an unrestricted life, allowing a person to be more fully themselves. This concept assumes that there is untapped human potential for creativity, compassion, and understanding that has been previously blocked or shut out.

How to Achieve Moksha

Moksha is obtained through the acquisition of knowledge and by overcoming ignorance . The three main ways to obtain moksha are known as “marga” . They are 1) “jnana”, the way of knowledge; 2) “bhakti”, the way of devotion; and 3) “karma” , the way of action. There are many sects, guides, teachers and gurus that provide assistance on the path to moksha. Yoga is among the methods that modern Hindus turn to in their quest for it (See Yoga). Moksha is not an easy thing to attain. It can thousands even millions of lifetimes to achieve.

In order to achieve release, the individual must pursue a kind of discipline (yoga, a "tying," related to the English word yoke) that is appropriate to one's abilities and station in life. For most people, this goal means a course of action that keeps them rather closely tied to the world and its ways, including the enjoyment of love (kama ), the attainment of wealth and power (artha ), and the following of socially acceptable ethical principles (dharma). [Source: Library of Congress]

From this perspective, even manuals on sexual love, such as the Kama Sutra (Book of Love), or collections of ideas on politics and governance, such as the Arthashastra (Science of Material Gain), are part of a religious tradition that values action in the world as long as it is performed with understanding, a karma-yoga or selfless discipline of action in which every action is offered as a sacrifice to God. Some people, however, may be interested in breaking the cycle of rebirth in this life or soon thereafter. For them, a wide range of techniques has evolved over the thousands of years that gives Indian religion its great diversity.

Yoga, Gurus and Achieving Moksha

The discipline that involves physical positioning of the body (hatha-yoga), which is most commonly equated with yoga outside of India, sees the human body as a series of spiritual centers that can be awakened through meditation and exercise, leading eventually to a oneness with the universe. Tantrism is the belief in the Tantra (from the Sanskrit, context or continuum), a collection of texts that stress the usefulness of rituals, carried out with a strict discipline, as a means for attaining understanding and spiritual awakening. These rituals include chanting powerful mantras; meditating on complicated or auspicious diagrams (mandalas); and, for one school of advanced practitioners, deliberately violating social norms on food, drink, and sexual relations. * [Source: Library of Congress]

A central aspect of all religious discipline, regardless of its emphasis, is the importance of the guru, or teacher. Indian religion may accept the sacredness of specific texts and rituals but stresses interpretation by a living practitioner who has personal experience of liberation and can pass down successful techniques to devoted followers.

Since Vedic times, it has never been possible, and has rarely been desired, to unite all people in India under one concept of orthodoxy with a single authority that could be presented to everyone. Instead, there has been a tendency to accept religious innovation and diversity as the natural result of personal experience by successive generations of gurus, who have tailored their messages to particular times, places, and peoples, and then passed down their knowledge to lines of disciples and social groups. As a result, Indian religion is a mass of ancient and modern traditions, some always preserved and some constantly changing, and the individual is relatively free to stress in his or her life the beliefs and religious behaviors that seem most effective on the path to deliverance. *

Tanrism

Tantrism is the belief in the Tantra (from the Sanskrit, context or continuum), a collection of texts that stress the usefulness of rituals, carried out with a strict discipline, as a means for attaining understanding and spiritual awakening. These rituals include chanting powerful mantras; meditating on complicated or auspicious diagrams (mandalas); and, for one school of advanced practitioners, deliberately violating social norms on food, drink, and sexual relations. * [Source: Library of Congress]

According to shivashakti.com: “Tantra, or more properly tantrika, is a diverse and rich spiritual tradition of the Indian sub-continent. Although in recent years, in the Western world, it has become almost exclusively associated with sex, in reality this is one aspect of what is a way of life. In India itself, tantra is now, nearly always, associated with spells and black deeds. Neither of these views is correct, and each wildly underestimates the wide-ranging nature of the different traditions. Further, there remains an ocean of tantrik and agamic literature still to be discovered and translated, spanning a period of time which at least reaches back to the 10th century, [Source: shivashakti.com *]

The tradition, or perhaps better, the traditions, underwent many phases and schools over this period of time, ranging from an extremely heterodox viewpoint to, in some cases, a very orthodox standpoint. The Kaula tradition alone has many guises. The work kaula is cognate with clan and the communities venerated a huge number of gods (devas) and goddesses (devis) and includes yantra, mantra, tantra and other material relating to some of the different traditions; texts on the siddhas, gurus and yogis of the Natha sampradaya including Gorakhnath, Matsyendranath and Dattatreya; much about kundalini, nadis, chakras; images of tantric kula devas (gods) and devis (goddesses) including Kali, Tripura, Shiva, Ganesha, Cchinnamasta, Durga and Tara; pujas and practices; meditations and dharanas; the inner meaning of kaulachara, vamachara and svecchacharya.

See Separate Article: TANTRISM factsanddetails.com

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024