AFTER WORLD WAR II: PREPARATIONS FOR INDEPENDENCE

At the end of World War II, Labor won control of the British Government and prepared to make India independent. India was prepared economically, since its war production had wiped out its debt to Britain. In 1946, the British proposed the creation of a single Indian state made up of a complicated tapestry of federations. Both Jinnah and Nehru approved the plan but an unfortunate, poorly-timed remark by Nehru at a press conference doomed the proposal. The major players in the negotiations for independence were Nehru, Jinnah and Lord Mountbatten and to a lesser degree Gandhi.

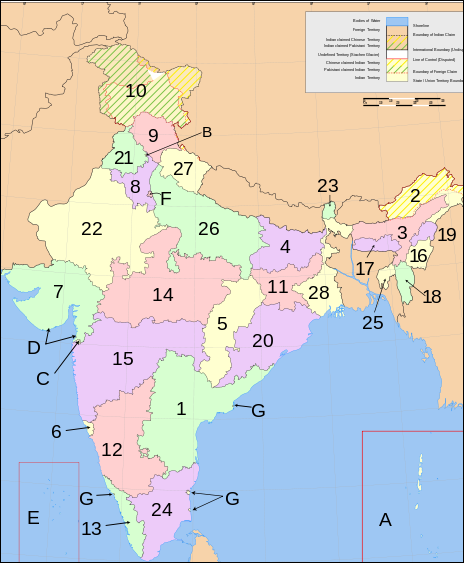

Before independence, about two fifth of South Asia was ruled by 600 kings and princes, the largest of which were Nepal and Hyderabad, Three fifths was ruled bu Britain. India absorbed all the princely states except for Nepal and Bhutan and then was split into thee units: India and Pakistan.

After World War II, the Congress wasted precious time denouncing the British rather than allaying Muslim fears during the highly charged election campaign of 1946. Even the more mature Congress leaders, especially Gandhi and Nehru, failed to see how genuinely afraid the Muslims were and how exhausted and weak the British had become in the aftermath of the war. When it appeared that the Congress had no desire to share power with the Muslim League at the center, Jinnah declared August 16, 1946, Direct Action Day, which brought communal rioting and massacre in many places in the north. Partition seemed preferable to civil war. On June 3, 1947, Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the viceroy (1947) and governor-general (1947-48), announced plans for partition of the British Indian Empire into the nations of India and Pakistan, which itself was divided into east and west wings on either side of India. At midnight, on August 15, 1947, India strode to freedom amidst ecstatic shouting of "Jai Hind" (roughly, Long Live India), when Nehru delivered a memorable and moving speech on India's "tryst with destiny." [Source: Library of Congress]

Churchill and Indian Independence

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: In the nineteen-twenties and thirties, [British Prime Minister Winston] Churchill had been loudest among the reactionaries who were determined not to lose India, “the jewel in the crown,” and, as Prime Minister during the Second World War, he tried every tactic to thwart Indian independence. “I hate Indians,” he declared. “They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.” He had a special animus for Gandhi, describing him as a “rascal” and a “half-naked” “fakir.” (In a letter to Churchill, Gandhi took the latter as a compliment, claiming that he was striving for even greater renunciation.) According to his own Secretary of State for India, Leopold Amery, Churchill knew “as much of the Indian problem as George III did of the American colonies.”[Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 13, 2007]

“In 1942, as the Japanese Army advanced on India, the Congress Party was willing to offer war support in return for immediate self-government. But Churchill was in no mood to negotiate. Frustrated by his stonewalling tactics, the Congress Party launched a vigorous “Quit India” campaign in August of 1942. The British suppressed it ruthlessly, imprisoning tens of thousands, including Gandhi and Nehru. Meanwhile, Churchill’s indispensable quartermaster Franklin D. Roosevelt was aware of the contradiction in claiming to fight for freedom and democracy while keeping India under foreign occupation. In letters and telegrams, he continually urged Churchill to move India toward self-government, only to receive replies that waffled and prevaricated. Muslims, Churchill once claimed, made up seventy-five per cent of the Indian Army (the actual figure was close to thirty-five), and none of them wanted to be ruled by the “Hindu priesthood.”

“Von Tunzelmann judges that Churchill, hoping to forestall independence by opportunistically supporting Muslim separatism, instead became “instrumental in creating the world’s first modern Islamic state.” This is a bit unfair—not to Churchill but to Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Though always keen to incite Muslim disaffection in his last years, the Anglicized, whiskey-drinking Jinnah was far from being an Islamic theocrat; he wanted a secular Pakistan, in which Muslims, Hindus, and Christians were equal before the law. (In fact, political Islam found only intermittent support within Pakistan until the nineteen-eighties, when the country’s military dictator, working with the Saudis and the C.I.A., turned the North-West Frontier province into the base of a global jihad against the Soviet occupation of neighboring Afghanistan.)

“What Leopold Amery denounced as Churchill’s “Hitler-like attitude” to India manifested itself most starkly during a famine, caused by a combination of war and mismanagement, that claimed between one and two million lives in Bengal in 1943. Urgently beseeched by Amery and the Indian viceroy to release food stocks for India, Churchill responded with a telegram asking why Gandhi hadn’t died yet. “It is strange,” George Orwell wrote in his diary in August, 1942, “but quite truly the way the British government is now behaving in India upsets me more than a military defeat.” Orwell, who produced many BBC broadcasts from London to India during the war, feared that “if these repressive measures in India are seemingly successful, the effects in this country will be very bad. All seems set for a big comeback by the reactionaries.” But in the British elections at the end of the war, the reactionaries unexpectedly lost to the Labour Party, and a new era in British politics began.

Nehru, Gandhi, Jinnah, Lord Mountbatten and Efforts to Create a Unified India

The negotiations between Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah for the handover of power from the British and the partition of India and Pakistan was overseen by Lord Louis Mountbatten, the final viceroy of India, and the great-grandson of Queen Victoria. Lord Mountbatten began work in March 1946 and worked at a feverish pace because it seemed that India was teetering on the edge of civil war. He sent frequent memos to his staff reminding them how little times was left. He also told them to be ready to leave the country on a moment’s notice in case the negotiations became unraveled and blew up in their faces.

Nehru, Gandhi and Mountbatten were all angered by Jinnah's stubbornness and his unwillingness to compromise. Nehru told Mountbatten that because success came so late in life to Jinnah he had a "permanently negative attitude." Jinnah regarded Nehru as a "busybody." Gandhi and Jinnah were formal to each other but not without invective. Gandhi once said of Jinnah, "You have mesmerized the Muslims." To which Jinnah retorted, "You have hypnotized the Hindus." Nehru said the plan to create a unified India was subject to change by the National Congress. Jinnah was apoplectic. Nehru was too proud to admit he might have made a mistake and India's last chance of becoming a single unified state collapsed. Jinnah was also angered by the statement "we cannot allow minorities to veto advances by the majority" made by the British prime minister. Jinnah responded, "The Muslims of India are not a minority but a nation, and self-determination is their birthright." Nehru and Jinnah also argued over whether Gandhi should be addressed as "Mister" or "Mahatma." Gandhi is partly blamed for the partition for not trying hard enough to keep Jinnah in the Indian National Congress and failing to object when the Jinnah attacked him by calling him "Mr. Gandhi" instead of "Mahatma." As a last ditch effort Jinnah was offered the prime ministership as a way of avoiding partition.

Riots in Calcutta in 1946

On August 16, 1946, a pro-Pakistan demonstration turned violent when Muslim mobs, allegedly organized by the Muslim League, set about killing Hindus and destroying their property. Local blacksmiths worked around the clock producing weapons and 72 hours later, piles of corpses lined the streets and 5,000 were dead. A Hindu butcher who organized a gang to seek revenge told Time, "I handed out guns, swords, grenades. For every dead Hindu, I ordered ten Muslim corpses."

According to a 1946 Time magazine account: "Rioting Moslems went after Hindus with guns, knives and clubs, looted shops, stoned newspaper offices, set fire to Calcutta's business districts. Hindus retaliated by setting fire to mosques and miles of Moslem slums...By the 21st day of Ramadan, direct action had killed some 3,000 people and wounded thousands more." One Hindu who refused to leave his home and was slashed across the head with an ax told Time: "There was tremendous fear all over the city. Friends and neighbors had suddenly become enemies." Recalling an assault on a Hindu neighbor he said, "The women were all screaming. The mob threw down one of the owners from the second floor. I saw a dead woman dragged by her legs. I remember wondering why there was no blood. I still have nightmares about that woman.”

The violence spread across Bengal and east India. Gandhi attempted to bring peace by walking from village to village in the troubled regions and reasoning with people to stop. The violence ended after a few months but not until thousands of homes were destroyed, hundreds of women were raped and an estimated 20,000 people died in riots in which Hindus promised Muslims a new state called "graveyard-stand." "The slaughter definitely made the partition inevitable," a Bangladeshi editor told Time in 1997. "It was the point of no return."

Creation of Pakistan

The sweep of Jinnah and Muslim League—who campaigned for partition—in predominately Muslim constituencies in the 1946 election, ensured the creation of Pakistan. After the massive riots in 1946-47, Indian and British leaders decided to divide India after independence in spite of Gandhi's objections. Jinnah wanted all of Bengal but accepted a “moth-eaten Pakistan” with East Bengal. Partition was announced on June 3 but the boundaries were not announced until after independence had been declared. Indians had to vote on whether to stay in India or join Pakistan and the leaders of 600 princely had to do the same. Baluchistan, the North-West Frontier provinces and the small kingdoms of the north voted to be in Pakistan, but the Hindu ruler of Kashmir hesitated which created problems there. In India, after partition, Muslims supported founding a secular state because the didn’t want to live in a Hindu one.

Pakistan was initially made up of two parts: East Pakistan and West Pakistan. The countries shared a common faith but they spoke different languages and were over 1,600 kilometers apart. East Pakistan consisted of the eastern half of Bengal and a few districts from Assam. West Pakistan was made up of the Sind, the North-West Frontier Province and the western half of Punjab. Several far-western princely and tribal states elected to join Pakistan as well.

See Separate Article DRIVE TOWARDS CREATING PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Sir Cyril Radcliffe, and Dividing India and Pakistan

The man selected to draw the lines on the map that divided India and Pakistan was Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a lawyer by training and former director general at the British Ministry of Information. Radcliffe had no training in cartography or demographics, and one of the main reason he was selected for the job was that he knew very little about India and was therefore judged to be relatively unbiased.

Radcliffe arrived in India without even knowing what his task was. On his first day in the country he was handed a pile of charts, maps and four-year-old census reports and told he had 36 days to divide India and Pakistan. "Radcliffe had never been east of Gibraltar in his life," his private secretary Christopher Beaumont told TIME, "and he was bit flummoxed by the whole thing. It was a rather impossible assignment, really. To partition the subcontinent in six weeks was absurd."

Radcliffe had no time to travel in India and the four Muslim judges and four Hindu judges that were assigned to help him were useless because they had the vested interests of their people at heart and some of them were probably spies for Indian National Congress, the Muslim League or the British. Radcliffe left Delhi on August 15, the day independence was declared, and was one of the first Englishman to leave after independence. "He was very thankful it was all over," Beaumont told TIME. He was so worried about assassination "a rigorous search of the airplane" was made before he took off.

On August 14, Radcliffe wrote his stepson, "Nobody in India will love me for the award about Punjab and Bengal, and there will be roughly 80 million people with a grievance who will begin looking for me. I don't want them to find me." Radcliffe returned the 2,000 pounds he'd been given for the project and remained close-lipped about his deed until his death. Sunil Khilnani, a historian and author “The Idea of India” wrote, Radcliffe "was without a doubt the Raj's most sphinxian figure, the guardian of the secret of its final and most decisive deed."

Independence and Partition for India in 1947

India became an independent nation at midnight on August 15, 1947, when the population of the sub continent was around 400 million people (about 320 million in India and 80 million in east and west Pakistan). This is about a forth of the number of people in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh today. The religious make up of subcontinent was 66 percent Hindu and 24 percent Muslim.

Partition refers to the historical division of the Indian subcontinent into India and Pakistan. The partition of India and Pakistan into the world's second and sixth most populous nations also occurred at midnight on August 15, 1947. To distinguish itself from India, Pakistan set its clock back 30 minutes. The countries have operated on time zones 30 minutes apart ever since.

Nehru became the Prime Minister of India and Jinnah was named the first Governor General and Qaid-e-Azamm ("the Great Leader") of Pakistan, the world's largest Muslim nation. Neither India or Pakistan celebrated the 50th anniversary in 1997 with much fanfare. The Pakistani government places a large "50" on the nose of its planes and held a few parades.

See Separate Articles PARTITION OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; VIOLENCE DURING THE PARTITION OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Indian states

Nehru's Independence Speech

In a famous speech that began a few minutes before midnight on August 14-15, 1947, Prime Minister Jawalarlal Nehru proclaimed the independence of India. Before a crowd of several hundred thousand people he declared: "Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and the now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to a life of freedom.”

"A moment comes but rarely in history when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends and when the soul of a nation long suppressed, finds utterance," Nehru said, "We end today a period of ill fortune and India discovers herself again. The achievement we celebrate today is but a step, an opening of opportunity, to the greater triumphs and achievements that await us. Are we brave and wise enough to grasp this opportunity and accept the challenge of the future?"

The speech has been called India's Gettysburg Address—"a consecration of victory and tragedy." To commemorate independence, Indian sitar-player Ravi Shankar composed the music for a ballet based Nehru's book “The Discovery of India”. Gandhi attended the performance and Nehru told him, "It's better than the book."

Geography and Conditions in India after Independence

At one time India consisted of hundreds of princely states. After independence they were merged into the 22 states of modern India. Portugal retained a colonial enclaves in Goa, Damao (a port settlement 100 miles north of Bombay) and Dui (including the island Dui and nearby mainland area, west f Damao) and France retained Pondicherry, Karikal and Yanam on the Coromandel Coast near Madras, Mahe on the Malabar Coast and Chandernagore in Bengal.

India became republic on January 26, 1950. It remained part of the British Commonwealth. By the time India became a republic in 1950, it had generally established its current boundaries. In the early 1950s, France peacefully yielded to India the five colonies of former French India: Pondicherry, Karikal, Mahe, Yanaon, and Chandernagor. In 1950, Chandernagore was joined to India in a plebiscite, and in 1954 France's other colonies were merged in India. In 1961, India seized Portuguese India. The former British protectorate of Sikkim—a Himalayan kingdom— became a protectorate of India in 1950 and was absorbed into India in 1974.

In 1947, India was unable to feed itself and was frequently plagued by famines. There was virtually no industry and the majority of people were illiterate and bound to the caste system. Some historians say that little happened politically in India after 1947 except that the British elite was replaced by an Indian one.

British and Indian Sentiments About Indian Independence

Describing the last days of the raj, novelist Paul Scot wrote that India and Britain had been "locked in an imperial embrace of such long standing and undoubtedly it was no longer possible for them to know whether they hated or loved one another."

Jan Morris, author of a history on the British Empire, wrote in Newsweek, "Britons...on the other side of the world had come to think of India as part of their own national identity, a permanent presence in the public consciousness, at once exotic and familiar. Innumerable British families, of all social rank, had sent their representatives to India, as soldiers, as business people, as administrators, as ne'er-do-well younger sons or as pious missionaries.

"When I was a child only intellectuals thought the British dominion of India had anything wicked to it," Morris wrote. "On the contrary, it was generally thought to be a providential bestowal of civilized values upon a backward and doubtless grateful conglomeration of people. Everyone knew...in general Indians were benighted heathens and unfortunates...and it was sort of a natural justice that Britons should go out and rule them."

In the novel “Sound the Retreat” by Simon Raven a Briton asks an Indian, "Why are you so keen to get rid of us?" The Indian replies, "Because Morrison sahib, we wish to order our own affairs. We shall not order them as efficiently as you do, my God, no, but then efficacy is not important to us, you understand." The Briton then said, "It's your fault. You will insist on the British leaving." The Indian replied, "Partly because we do not like being spoken to in that tone of voice."

British Legacy on India and Indian Legacy on Britain

Many Britons look back on what they left behind in India as an inheritance rather than legacy, including institutions to maintain order, justice and democracy. Some are more cynical. Journalist Christopher called partition the replacement of "divide and rule" with "divide and quit".

The British established and left behind an infrastructure and administration for a modern state—including a postal and telegraph system, railways, canals, roads, universities, grand Victorian buildings, statues of Queen Victoria and Robert Clive, courts, assemblies, a disciplined non-political army, and a well-organized administrative system made up of dedicated civil servants.

Perhaps the most important thing the British left behind was the English language. English provided a common tongue for administration and education and gave people from a polyglot nation a common language. The Indian constitution and Indian legal code are written in English and the famous independence speech by Nehru was delivered in English.

India gave Britain curries, tea, verandas, bungalows, cotton, gin and tonics, pierced noses, spiritual enlightenment, Pakistani-run grocery stores, inspiration for a pile of literary classic and a rich infusion of the exotic. Cigars, polo and shows were all Indian habits introduced to the West by the British.

Indian Independence: the End of Colonialism?

Some historians have argued that for all intents and purposes the independence of India was the last chapter of the Age of Imperialism which had begun with Columbus, the Portuguese and the Spanish conquistadors. After 1947, the British Empire shed its African colonies and finally relinquished it last major holding Hong Kong, 50 years after losing India. "By the 1970s the very world "empire" had become disreputable," Morris wrote. "Even Rudyard Kipling, the poet laureate of Anglo-Indian and the British Empire, went disastrously out of fashion."

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2020