SEPOY MUTINY AROUSES NATIONAL SENTIMENTS IN INDIA

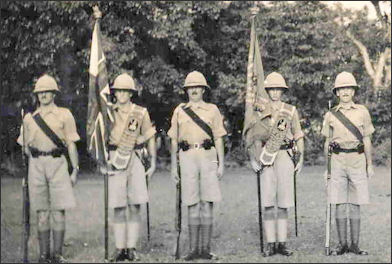

India Royal Norfolks 1933 After the Sepoy Rebellion in 1858, Indians became increasing agitated with British rule and colonial inequality. At the end of 19th century, there were reform sentiments among Westernized urban elite, many of whom were educated in English language schools in India and Britain. In the 20th century religion became irremovably linked with nationalism in India and continued even after independence and the split of India and Pakistan.

After the East India Company was replaced by the British Raj in 1858 many existing economic and revenue policies remained virtually unchanged in the post-1857 period, but several administrative modifications were introduced, beginning with the creation in London of a cabinet post, the secretary of state for India. The governor-general (called viceroy when acting as the direct representative of the British crown), headquartered in Calcutta, ran the administration in India, assisted by executive and legislative councils. Beneath the governor-general were the provincial governors, who held power over the district officials, who formed the lower rungs of the Indian Civil Service. For decades the Indian Civil Service was the exclusive preserve of the British-born, as were the superior ranks in such other professions as law and medicine. The British administrators were imbued with a sense of duty in ruling India and were rewarded with good salaries, high status, and opportunities for promotion. Not until the 1910s did the British reluctantly permit a few Indians into their cadre as the number of English-educated Indians rose steadily. [Source: Library of Congress *]

British attitudes toward Indians shifted from relative openness to insularity and xenophobia, even against those with comparable background and achievement as well as loyalty. British families and their servants lived in cantonments at a distance from Indian settlements. Private clubs where the British gathered for social interaction became symbols of exclusivity and snobbery that refused to disappear decades after the British had left India. In 1883 the government of India attempted to remove race barriers in criminal jurisdictions by introducing a bill empowering Indian judges to adjudicate offenses committed by Europeans. Public protests and editorials in the British press, however, forced the viceroy, George Robinson, Marquis of Ripon (who served from 1880 to 1884), to capitulate and modify the bill drastically. The Bengali Hindu intelligentsia learned a valuable political lesson from this "white mutiny": the effectiveness of well-orchestrated agitation through demonstrations in the streets and publicity in the media when seeking redress for real and imagined grievances. *

See Separate Article SEPOY MUTINY factsanddetails.com

The decades following the Sepoy Rebellion were a period of growing political awareness, manifestation of Indian public opinion, and emergence of Indian leadership at national and provincial levels. Ominous economic uncertainties created by British colonial rule and the limited opportunities that awaited the ever-expanding number of Western-educated graduates began to dominate the rhetoric of leaders who had begun to think of themselves as a "nation," despite fissures along the lines of region, religion, language, and caste. *

Indians had the will to fight against British rule but their resistance movement lacked unity and direction until Mohandus Gandhi became the leader of the Indian National Congress in 1920 and independence became a cause embraced by India's multitudes. The Indian Councils Act of 1909 enhanced role of elected province legislatures in India.

Books: “The Proudest Day, India's Long Road to Independence” by Anthony Read and David Fisher (Norton, 1998); “Liberty or Death: India's Journey to Independence and Division” by Patrick French.

Birth of Nationalism in India

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations: While the British moved gradually to expand local self-rule along federal lines, British power was increasingly challenged by the rise of indigenous movements challenging its authority. A modern Indian nationalism began to grow as a result of the influence of Western culture and education among the elite, and the formation of such groups as the Arya Samaj and Indian National Congress. Founded as an Anglophile debating society in 1885, the congress grew into a movement leading agitation for greater self-rule in the first 30 years of this century. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: “With the setting up of government universities, an Indian middle class had begun to emerge and to advocate further reform. Among the leaders who organized the Indian National Congress in 1885 were Allan Octavian Hume, retired from the Indian Civil Service, Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, and W. C. Bonnerjee. Later in the century, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Surendranath Banerjea, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Rabindranath Tagore, and Aurobindo Ghose also rose to prominence. The nationalist movement had been foreshadowed earlier in the century in the writings of Rammohun Roy. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

“Popular nationalist sentiment was perhaps most strongly aroused when, for administrative reasons, Viceroy Curzon partitioned (1905) Bengal into two presidencies; newly created Eastern Bengal had a Muslim majority. (The partition was ended in 1911.) In the early 1900s the British had widened Indian participation in legislative councils (the Morley-Minto reforms). Separate Muslim constituencies, introduced for the first time, were to be a major factor in the growing split between the two communities. Muslim nationalist sentiment was expressed by Sayyid Ahmad Khan, Muhammad Iqbal, and Muhammad Ali.

Mridu Rai wrote in the Encyclopedia of Modern Europe: “The emergence of a structured movement of anti-colonial resistance in India is conventionally traced to the Indian National Congress established in December 1885. Its early membership was elite, urban, and Western-educated. Its methods and demands were moderate, petitioning for greater Indian participation in imperial governance and economic policies that would develop, not impoverish, India. Gradually a more militant strand emerged that declared self-rule a "birthright" and advocated assertive strategies of boycott to achieve it. These "extremists" also reached out to the masses but the symbols around which they mobilized—Hindu deities and historical figures—often alienated religious minorities. [Source: Mridu Rai, Encyclopedia of Modern Europe: Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction, Thomson Gale, 2006]

“Forming a quarter of India's population, most Muslims remained aloof from the Congress. Indeed, the reformer Syed Ahmed Khan (1817–1898) had warned that political activism by a community lagging educationally and economically behind the Hindu majority would mean its eventual obliteration. In December 1906, a few leading Muslims gathered in Dacca (eastern Bengal) to found the All India Muslim League. Earlier in October, a delegation of Muslim landlords had met with the viceroy to demand separate electorates and weighted representation for Muslims, a concession embodied in the Indian Councils Act of 1909. Elite Muslim and imperial interests dovetailed to represent Indians as divided into distinct communities requiring separate representation.

Sir William Jones, Rammuohun Roy and Early Indian Reformers and Modernists

Sir William Jones, the great oriental linguist of the 18th century, translated a slew of ancient Sanskrit texts into English thereby removing them from the grasp of the Brahmins who had used their literacy as a source of power over other Indians. Describing Jones, V.S. Naipaul wrote: he "brought many of the attitudes of the 18th century enlightenment to India. In the cultural ruins of much conquered India he saw himself like a man of the Renaissance in the ruins of the classical world...He and people like him, gave Indians the first ideas they had of antiquity and value of their civilization. Those ideas gave strength to the nationalist movement more than 100 years later.”

Rammuohun Roy (1772-1833) is often called the "Father of Modern India." Educated in Arabic and author of a book entitled “The Principles of Jesus: The Guide to Peace and Happiness”, he led a movement that outlawed widow burning, conducting Hindu meetings like Protestant services and introduced English schooling. Roy rejected Western politics but supported the introduction of Western technology and even found examples for the existence of the railroad and telegraph in ancient texts. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Arya Samaj, another important reformer who took on the guise of medieval mendicant, led the "back to Veda" movement which implied that all classes (not just Brahmans) were welcome in the priesthood and the full blown caste system and idolatry were wrong. A third reformer, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1834-1886) called for a return to devotion and meditation. He once went into a trance for six months and was saved from starvation only because his followers forced food upon him. One of Paramahamsa's followers, Swaimi Vivekanada, attended the parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893 and returned with Western followers and was instantly famous.

Early Nationalist Parties in India

In the late 19th and early 20th century, British power was challenged by the rise of nationalist mass movements. The Indian National Congress began attracting wide support in the 1920 with its advocacy of nonviolent struggle. But because its leadership style appeared, to many Muslims, to be uniquely Hindu, Muslims formed the All-India Muslim League to look after their interests. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale. 2007]

The Indian National Congress, a Hindu-dominated political organization, was founded in 1885 and supported by the Calcutta elite. It had both Indian and British members. It was founded by 72 lawyers, journalist and academics in Bombay. The Indian National Congress (INC) became the major vehicle of the Indian independence movement and still is a major political force today. Bombay. The founding members included 68 Hindus and 2 Muslims and a 73-year-old retired British civil servant named Allan Octavian Hume, who felt that the British colonial rulers were unresponsive to the needs of the Indian people. For the first 30 years of it existence the Congress operated in Bombay with financial help from wealthy merchants. [Source: Library of Congress]

Muslims seeking an organization of their own founded the All-India Muslim League in 1906. It sought separate communal representation. For many Muslims, loyalty to the British crown seemed preferable to cooperation with Congress leaders. Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan (1817-98) launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1921). Its objective was to educate wealthy students by emphasizing the compatibility of Islam with modern Western knowledge. The diversity among India's Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

According to Countries of the World and Their Leaders The subsequent history of the nationalist movement was characterized by periods of Hindu-Muslim cooperation, as well as by communal antagonism. Although both the League and the Congress supported the goal of Indian self-government within the British Empire, the two parties were unable to agree on a way to ensure the protection of Muslim political, social, and economic rights. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009]

Founding of the Indian Nationalist Congress

The Indian National Congress political party was founded in 1885. It was central to India's independence movement and was the dominant ruling party from 1947 until fairly recently. Over 70 self-appointed delegates from across India participated in the Congress's first meeting. By 1887, the Congress included 600 members, a number that grew to 2,000 in 1889; delegates were Hindu, Muslim, Parsi, and Jain and belonged to the middle or upper classes. In its first decades, the Congress agitated for increased Indian representation in the civil service and government, jobs held at the time mostly by British citizens.

On December 28, 1885, seventy-two lawyers, journalist and academics founded the Indian National Congress (INC)—which became the major vehicle of the Indian independence movement and still is a major political force today— in Bombay. The founding members included 68 Hindus and 2 Muslims and a 73-year-old retired British civil servant named Allan Octavian Hume, who felt that the British colonial rulers were unresponsive to the needs of the Indian people. For the first 30 years of it existence the Congress operated in Bombay with financial help from wealthy merchants.

Inspired by a suggestion made by Hume, the founding members of the Indian National Congress were mostly members of the upwardly mobile and successful Western-educated provincial elites, engaged in professions such as law, teaching, and journalism. They had acquired political experience from regional competition in the professions and from their aspirations in securing nomination to various positions in legislative councils, universities, and special commissions. [Source: Library of Congress]

At its inception, the Congress had no well-defined ideology and commanded few of the resources essential to a political organization. It functioned more as a debating society that met annually to express its loyalty to the Raj and passed numerous resolutions on less controversial issues such as civil rights or opportunities in government, especially the civil service. These resolutions were submitted to the viceroy's government and, occasionally, to the British Parliament, but the Congress's early gains were meager. Despite its claim to represent all India, the Congress voiced the interests of urban elites; the number of participants from other economic backgrounds remained negligible.

Almost immediately after its creation the INC demanded a greater voice for Indians in government. By the end of the 19th century the Congress became the representative of India's Hindu majority Among its early members were Motilal Nehru, the patriarch of a dynasty that would produce three Indian prime ministers. By 1900, although the Congress had emerged as an all-India political organization, its achievement was undermined by its singular failure to attract Muslims, who had by then begun to realize their inadequate education and underrepresentation in government service. Muslim leaders saw that their community had fallen behind the Hindus. Attacks by Hindu reformers against religious conversion, cow killing, and the preservation of Urdu in Arabic script deepened their fears of minority status and denial of their rights if the Congress alone were to represent the people of India.

Beginning in 1920, Indian leader Mohandas K. Gandhi transformed the Indian National Congress political party into a mass movement to campaign against British colonial rule. Under Gandhi in the 1920s and 1930s, the Congress Party made purna swaraj (complete independence) and a representative form of government its primary objectives. To that end, the Congress supported satyagraha, civil disobedience campaigns, against British taxes. The party used both parliamentary and nonviolent resistance and non-cooperation to agitate for independence.

Founding of the Muslim League in 1906

“The Muslim League was a political organization formed in December 1906 to defend the rights of Muslims in India against the Hindu majority. during British colonial rule. The League helped establish the independent nation of Pakistan. In the early 20th century, Muslims did not believe the National Congress represented their interests. Initially, the League adopted the same objective as the Congress—self-government for India within the British Empire—but Congress and the League were unable to agree on a formula that would ensure the protection of Muslim religious, economic, and political rights. The Muslim League sought separate communal representation. The India Councils Act of 1909 addressed Muslim grievances that they were being discriminated against by granting them their own representatives to the Legislative Council. This move was seen by some historians as the first step in the creation of Pakistan.

The Muslim League sought separate communal representation. For many Muslims, loyalty to the British crown seemed preferable to cooperation with Congress leaders. Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan (1817-98) launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1921). Its objective was to educate wealthy students by emphasizing the compatibility of Islam with modern Western knowledge. The diversity among India's Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

In 1906 the All-India Muslim League (Muslim League) met in Dhaka for the first time. The Muslim League used the occasion to declare its support for the partition of Bengal and to proclaim its mission as a "political association to protect and advance the political rights and interests of the Mussalmans of India." Muslim League was founded in Dhaka to promote loyalty to the British and "to protect and advance the political rights of the Muslims of India and respectfully represent their needs and aspirations to the Government." It was also stated that there was no intention to affect the rights of other religious groups. Earlier that same year, a group of Muslims — the Simla Delegation — led by Aga Khan III, met the viceroy and put forward the concept of "separate electorates." If the proposal were accepted, Muslim members of elected bodies would be chosen from electorates composed of Muslims only, and the number of seats in the elected bodies allotted to Muslims would be at least proportional to the Muslim share of the population, but preferably "weighted" to give Muslims a share in seats somewhat higher than their proportion of the population. The principles of communal representation, separate electorates, and weightage were included in the Government of India Act of 1909 and were expanded to include such other groups as Sikhs and Christians in later constitutional enactments. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

See Separate Article MUSLIM LEAGUE AND MUSLIM-HINDU DIVISIONS IN BENGAL (1900-1945) factsanddetails.com

Beginnings of Self-Government in India

In the late 1800s, the first steps were taken toward self-government in British India with the appointment of Indian councilors to advise the British Viceroy and the establishment of Provincial Councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in Legislative Councils.[Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

The Government of India Act of 1909 — also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley was the secretary of state for India, and Gilbert Elliot, fourth earl of Minto, was viceroy) — gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures, known as legislative councils. Indians had previously been appointed to legislative councils, but after the reforms some were elected to them. At the center, the majority of council members continued to be government-appointed officials, and the viceroy was in no way responsible to the legislature. At the provincial level, the elected members, together with unofficial appointees, outnumbered the appointed officials, but responsibility of the governor to the legislature was not contemplated. Morley made it clear in introducing the legislation to the British Parliament that parliamentary self-government was not the goal of the British government. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

The Morley-Minto Reforms were a milestone. Step by step, the elective principle was introduced for membership in Indian legislative councils. The "electorate" was limited, however, to a small group of upper-class Indians. These elected members increasingly became an "opposition" to the "official government." Communal electorates were later extended to other communities and made a political factor of the Indian tendency toward group identification through religion. The practice created certain vital questions for all concerned. The intentions of the British were questioned. How humanitarian was their concern for the minorities? Were separate electorates a manifestation of "divide and rule"? *

In August 1917, the British government formally announced a policy of "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." Constitutional reforms were embodied in the Government of India Act of 1919 — also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (Edwin Samuel Montagu was Britain's secretary of state for India; the Marquess of Chelmsford was viceroy). These reforms represented the maximum concessions the British were prepared to make at that time. The franchise was extended, and increased authority was given to central and provincial legislative councils, but the viceroy remained responsible only to London.

The changes at the provincial level were significant, as the provincial legislative councils contained a considerable majority of elected members. In a system called "dyarchy," the nation- building departments of government — agriculture, education, public works, and the like — were placed under ministers who were individually responsible to the legislature. The departments that made up the "steel frame" of British rule — finance, revenue, and home affairs — were retained by executive councillors who were often, but not always, British and who were responsible to the governor.

The 1919 reforms did not satisfy political demands in India. The British repressed opposition, and restrictions on the press and on movement were reenacted. An apparently unwitting example of violation of rules against the gathering of people led to the massacre at Jalianwala Bagh in Amritsar in April 1919. This tragedy galvanized such political leaders as Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) and the masses who followed them to press for further action.

World War I, Reforms, and Agitation in India

World War I began with an unprecedented outpouring of loyalty and goodwill toward the British, contrary to initial British fears of an Indian revolt. India contributed generously to the British war effort, by providing men and resources. About 1.3 million Indian soldiers and laborers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, while both the Indian government and the princes sent large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. But disillusionment set in early. High casualty rates, soaring inflation compounded by heavy taxation, a widespread influenza epidemic, and the disruption of trade during the war escalated human suffering in India. The prewar nationalist movement revived as moderate and extremist groups within the Congress submerged their differences in order to stand as a unified front. The Congress even succeeded in forging a temporary alliance with the Muslim League — the Lucknow Pact, or Congress-League Scheme of Reforms — in 1916, over the issues of devolution of political power and the future of Islam in the Middle East. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The British themselves adopted a "carrot and stick" approach in recognition of India's support during the war and in response to renewed nationalist demands. In August 1917, Edwin Montagu, the secretary of state for India, made the historic announcement in Parliament that the British policy for India was "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." The means of achieving the proposed measure were later enshrined in the Government of India Act of 1919, which introduced the principle of a dual mode of administration, or dyarchy, in which both elected Indian legislators and appointed British officials shared power. The act also expanded the central and provincial legislatures and widened the franchise considerably. Dyarchy set in motion certain real changes at the provincial level: a number of noncontroversial or "transferred" portfolios — such as agriculture, local government, health, education, and public works — were handed over to Indians, while more sensitive matters such as finance, taxation, and maintaining law and order were retained by the provincial British administrators. *

The positive impact of reform was seriously undermined in 1919 by the Rowlatt Acts, named after the recommendations made the previous year to the Imperial Legislative Council by the Rowlatt Commission, which had been appointed to investigate "seditious conspiracy." The Rowlatt Acts, also known as the Black Acts, vested the viceroy's government with extraordinary powers to quell sedition by silencing the press, detaining political activists without trial, and arresting any suspected individuals without a warrant. No sooner had the acts come into force in March 1919 — despite opposition by Indian members on the Imperial Legislative Council — than a nationwide cessation of work (hartal ) was called by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948). Others took up his call, marking the beginning of widespread — although not nationwide — popular discontent. The agitation unleashed by the acts culminated on April 13, 1919, in Amritsar, Punjab. The British military commander, Brigadier Reginald E.H. Dyer, ordered his soldiers to fire at point-blank range into an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of some 10,000 men, women, and children. They had assembled at Jallianwala Bagh, a walled garden, to celebrate a Hindu festival without prior knowledge of the imposition of martial law. A total of 1,650 rounds were fired, killing 379 persons and wounding 1,137 in the episode, which dispelled wartime hopes and goodwill in a frenzy of postwar reaction. *

Partition of Bengal and Political Activity After That

The east Indian state of Bengal was divided into the predominately Muslim eastern and predominately Hindu western provinces in 1905, but after a period of anarchy and violence, it was reunited in 1911 at the request of Hindus. Muslims were angered by this. Muslims were also repulsed by perceived aggressions towards Muslims by Europeans in Libya, Morocco, Persia and Turkey.

Sir George Curzon, the governor-general (1899-1905), ordered the partition of Bengal in 1905. He wanted to improve administrative efficiency in that huge and populous region, where the Bengali Hindu intelligentsia exerted considerable influence on local and national politics. The partition created two provinces: Eastern Bengal and Assam, with its capital at Dhaka (then spelled Dacca), and West Bengal, with its capital at Calcutta (which also served as the capital of British India). An ill-conceived and hastily implemented action, the partition outraged Bengalis. Not only had the government failed to consult Indian public opinion but the action appeared to reflect the British resolve to "divide and rule." Widespread agitation ensued in the streets and in the press, and the Congress advocated boycotting British products under the banner of swadeshi. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Congress-led boycott of British goods was so successful that it unleashed anti-British forces to an extent unknown since the Sepoy Rebellion. A cycle of violence, terrorism, and repression ensued in some parts of the country. The British tried to mitigate the situation by announcing a series of constitutional reforms in 1909 and by appointing a few moderates to the imperial and provincial councils. In 1906 a Muslim deputation met with the viceroy, Gilbert John Elliot (1905-10), seeking concessions from the impending constitutional reforms, including special considerations in government service and electorates. The All-India Muslim League was founded the same year to promote loyalty to the British and to advance Muslim political rights, which the British recognized by increasing the number of elective offices reserved for Muslims in the India Councils Act of 1909. The Muslim League insisted on its separateness from the Hindu-dominated Congress, as the voice of a "nation within a nation." *

In what the British saw as an additional goodwill gesture, in 1911 King-Emperor George (1910-36) visited India for a durbar (a traditional court held for subjects to express fealty to their ruler), during which he announced the reversal of the partition of Bengal and the transfer of the capital from Calcutta to a newly planned city to be built immediately south of Delhi, which became New Delhi.

Massacre at Jallianwalla Bagh

Anti-British sentiments were inflamed by the massacre of hundreds of Indians by British troops at Amritsar's Jallianwalla Bagh public garden on April 13, 1919. Following orders by the self-made general, R.E.H. Dyer, British troops opened fire on 10,000 unarmed civilians who were packed inside a walled garden. They had gathered to protest new laws allowing political protesters to be jailed without formal charges. The exits were blocked by British armored cars.

The British say 379 unarmed Indians were killed and 1,200 were wounded. Indians say more than 2,0000 died, many of whom were found dead in well or were crushed to death in the stampede that folllowed the shots. General Dyer's original intent was to set an example to deter other protests. But then Dyer went further. He ordered Indian sympathizers to be publicly flogged in the streets and ordered all Indians to prostrate themselves and crawl on their bellies past the alleged site of an attack on an English woman.

Indians were outraged and appalled. Many Indian men had just returned from Europe, where they fought for Britain in World War I. They thought: and this is the thanks we get. The Nobel-laureate poet Rabundranth Tagore renounced his knighthood and Mahatma Gandhi was roused to begin his campaign of disobedience the next year. In Amritsar today, there is a statue honoring the man who gunned down the governor of Punjab who approved the massacre.

General Dyer received a slap-on-the wrist censure by a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry and then was praised in a resolution passed by the British House of Lords. From that moment on, for Indian nationalists, the question was no longer if they could get rid of their British rulers but how soon this goal could be achieved. A sign at the entrance of Jallianwala Bagh today reads: “This place is saturated with the blood of about 2,000 Hindu, Sikh and Muslim patriots who were martyred in a non-violent struggle to free India from British domination.”

Political Reforms in the 1920s and 30s

The political picture in India was not at all clear when the mandated decennial review of the Government of India Act of 1919 became due in 1929. Prospects of further constitutional reforms spurred greater agitation and a frenzy of demands from different groups. The commission in charge of the review was headed by Sir John Simon, who recommended further constitutional change, but it was not until 1935 that a new Government of India Act was passed. Three consecutive roundtable conferences were held in London in 1930, 1931, and 1932, at which a wide variety of interests from India were represented. The major disagreement concerned the continuation of separate electorates, which Gandhi and Congress strongly opposed. As a result, the decision was forced on the British government. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald issued his "communal award," which continued the system of separate electorates at both the central and the provincial level.

The principal result of the act was "provincial autonomy." The dyarchical system was discontinued, and all subjects were placed under ministers who were individually and collectively responsible to the former legislative councils, which were renamed legislative assemblies. (In a few provinces, including Bengal, a bicameral system was established; the upper house continued to be called a legislative council.) Almost all assembly members were elected, with the exception of some special and otherwise unrepresented groups. After the elections, provincial chief ministers and cabinets took office, although the governors had limited "emergency powers." Sindh was separated from Bombay and became a province. The 1919 reforms had earlier been introduced in the North-West Frontier Province. Balochistan, however, retained special status; it had no legislature and was governed by an "agent general to the governor general." At the center, the act essentially provided for the establishment of dyarchy, but it also provided for a federal system that included the princes. The princes refused to join a system that might force them to accept decisions made by elected politicians. Thus, the full provisions of the 1935 act did not come into force at the center.

Indian National Congress Gains Momentum in the 1930s

Under Gandhi and other nationalist leaders, such as Motilal and Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian National Congress began to attract mass support in the 1930s. The success of noncooperation campaigns spearheaded by Gandhi and its advocacy of education, cottage industries, self-help, an end to the caste system, and nonviolent struggle was attractive to many Indians. Muslims had also been politicized, beginning with the abortive partition of Bengal during the period 1905–12. And despite the INC leadership's commitment to secularism, as the movement evolved under Gandhi, its leadership style appeared—to Muslims—uniquely Hindu, leading Indian Muslims to look to the protection of their interests in the formation of their own organization, the All-India Muslim League. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“National and provincial elections in the mid-1930s, coupled with growing unrest throughout India, persuaded many Muslims that the power the majority Hindu population could exercise at the ballot box could leave them as a permanent electoral minority in any single democratic polity that would follow British rule. Sentiment in the Muslim League began to coalesce around the "two nation" theory propounded by the poet Iqbal, who argued that Muslims and Hindus were separate nations and that Muslims required creation of an independent Islamic state for their protection and fulfillment. A prominent attorney, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, led the fight for a separate Muslim state to be known as Pakistan, a goal formally endorsed by the Muslim League in Lahore in 1940. By 1947, the Congress was a diverse party, including members of various castes and linguistic and religious groups. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2020