ALEXANDER'S TROOPS MUTINY

Alexander quelling the Opis mutiny

Alexander's next goal was to reach the Ganges River, which was actually 400 kilometers away, a considerable distance, because he thought that it flowed into the outer Ocean. His troops, however, had heard tales of the powerful Indian tribes that lived on the Ganges and remembered the difficulty of the battle with Porus, so they refused to go any farther east.

On the banks of the Hyphias (now Beas) River, Alexander ordered his men to head east, the men refused. Alexander was enraged and was little consoled by the words of one of his noble advisors, who told him, "A noble thing, O king, is to know when to stop.” Alexander reacted by saying anyone who disobeyed him would be accused of desertion and went to his tent to sulk. After confining himself to his tent from three days, he consulted his omens and was conveniently told he trouble awaited him in India. On hearing the news his men shouted: "Alexander allowed us, but no others, to defeat him."Alexander then decided to head back home. In retrospect this may have been a hasty decision as a major Indian army had already been defeated and all of India was within their grasp. Alexander was extremely disappointed, but he accepted their decision and persuaded them to travel south down the rivers Hydaspes and Indus to reach the Arabian Sea and ships that would take them home.

Plutarch wrote: “On the banks of the Hyphias (now Beas) River, Alexander ordered his men to head east, the men refused. Alexander was enraged and was little consoled by the words of one of his noble advisors, who told him, "A noble thing, O king, is to know when to stop." Alexander reacted by saying anyone who disobeyed him would be accused of desertion and went to his tent to sulk. After confining himself to his tent from three days, he consulted his omens and was conveniently told he trouble awaited him in India. On hearing the news his men shouted: "Alexander allowed us, but no others, to defeat him."Alexander then decided to head back home. In retrospect this may have been a hasty decision as a major Indian army had already been defeated and all of India was within their grasp. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“But this last combat with Porus took off the edge of the Macedonians’ courage, and stayed their further progress into India. For having found it hard enough to defeat an enemy who brought but twenty thousand foot and two thousand horse into the field, they thought they had reason to oppose Alexander’s design of leading them on to pass the Ganges too, which they were told was thirty-two furlongs broad and a hundred fathoms deep, and the banks on the further side covered with multitudes of enemies. For they were told that the kings of the Gandaritans and Præsians expected them there with eighty thousand horse, two hundred thousand foot, eight thousand armed chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants. Nor was this a mere vain report, spread to discourage them. For Androcottus,* who not long after reigned in those parts, made a present of five hundred elephants at once to Seleucus, and with an army of six hundred thousand men subdued all India.

“Alexander at first was so grieved and enraged at his men’s reluctancy, that he shut himself up in his tent, and threw himself upon the ground, declaring, if they would not pass the Ganges, he owed them no thanks for any thing they had hitherto done, and that to retreat now, was plainly to confess himself vanquished. But at last the reasonable persuasions of his friends and the cries and lamentations of his soldiers, who in a suppliant manner crowded about the entrance of his tent, prevailed with him to think of returning. Yet he could not refrain from leaving behind him various deceptive memorials of his expedition, to impose upon after-times, and to exaggerate his glory with posterity, such as arms larger than were really worn, and mangers for horses, with bits of bridles above the usual size, which he set up, and distributed in several places. He erected altars, also, to the gods, which the kings of the Præsians even in our time do honor to when they pass the river, and offer sacrifice upon them after the Grecian manner. Androcottus, then a boy, saw Alexander there, and is said often afterwards to have been heard to say, that he missed but little of making himself master of those countries; their king, who then reigned, was so hated and despised for the viciousness of his life, and the meanness of his extraction.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356 TO 324 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S LEADERSHIP, TACTICS, ARMY, GENERALS AND MILITARY SKILLS europe.factsanddetails.com

ALEXANDER THE GREAT DEFEATS THE PERSIANS AT GAUGAMELA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT IN PAKISTAN-INDIA factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S BATTLE WITH PORUS AND WHAT THE GREEKS LEFT BEHIND IN INDIA factsanddetails.com ; ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S RETURN JOURNEY factsanddetails.com

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Hydaspes 326 BC: The Limit of Alexander the Great’s Conquests”

by Nic Fields and Marco Capparoni (2023) Amazon.com;

“On Alexander's Track to the Indus: Personal Narrative of Explorations on the North-West Frontier of India” by Aurel Stein (1862-1943) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great in India” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

"Invasion of India by Alexander the Great" by J.W. M'Crindle M'Crindle | Mar 6, 2025 Amazon.com;

“Mighty Porus and Alexander The Great: The Clash of Two Giants” (2020)

by Biren Trivedi (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Hellenistic Far East: Archaeology, Language, and Identity in Greek Central Asia”

by Rachel Mairs (2014) Amazon.com;

“Alexander & Hephaestion: Their Lives and Unique Love as Recorded by Plutarch, Diodorus, Justin and Others” by Michael Hone (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bucephalus: Warhorse of Alexander the Great” by Douglas A Dowell (2024), mainly for kids Amazon.com;

“In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great” by Michael Wood (1997) Amazon.com;

“Conquest and Empire” by A. B Bosworth (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Generalship of Alexander the Great” by J. F. C. Fuller (1958) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great at War: His Army — His Battles — His Enemies” by Ruth Sheppard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Field Campaigns of Alexander the Great” by Stephen English Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army” by Donald W. Engels (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Army of Alexander the Great” (Men at Arms Series), Illustrated, by Nicholas Sekunda (1992) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Primary Sources:(Also available for free at MIT Classics, Gutenberg.org and other Internet sources):

“History of Alexander” by Quintus Curtius Rufus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica” by Arrian (Oxford World Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander” by Arrian Amazon.com;

“The Life of Alexander the Great” by Plutarch (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

Why Did Alexander the Great’s Army Refuse to Advance?

By the time of the defeat of Porus in India, the monsoons had set in and Alexander's men were wet to the bone, tired, homesick and mutinous and perhaps scared of facing off against the Nandas, their next foes, who were referred to in Greeks texts and possessing a formidable army and controlling the Mauryan Empire. Alexander biographer Lane Fox told Smithsonian magazine, “It was pelting with rain, the men were terrified, there snakes everywhere. They were lost and did not feel they could go on anymore." Historian Peter Green told National Geographic, Alexander was basically screwed by ignorance of geography. He had been telling his men, We'll just go over the hill, boys — and then suddenly he had the whole of the Ganges plain before him."

Arrian wrote: “It was reported that the country beyond the river Hyphasis was fertile, and that the men were good agriculturists, and gallant in war; and that they conducted their own political affairs in a regular and constitutional manner. For the multitude was ruled by the aristocracy, who governed in no respect contrary to the rules of moderation. It was also stated that the men of that district possessed a much greater number of elephants than the other Indians, and that those men were of very great stature, and excelled in valour. These reports excited in Alexander an ardent desire to advance farther; but the spirit of the Macedonians now began to flag, when they saw the king raising one labour after another, and incurring one danger after another. Conferences were held throughout the camp, in which those who were the most moderate bewailed their lot, while others resolutely declared that they would not follow Alexander any farther, even if he should lead the way. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

Rama Shankar Tripathi wrote: “It is true the Greek soldiers were war-worn, home-sick, disease-stricken, and destitute; and many of them were ill-equipped, for it was now increasingly difficult to transport and supply garments from Greece, and not a few were depressed because their friends had perished by disease or fallen victims to sanguinary battles. But was there any other ground for their conduct which doubtless savoured of mutiny ? Plutarch gives us some clue to this mystery, for he indicates that even after the contest with Poros the Macedonian forces were considerably dispirited, and it was with reluctance that they had advanced as far as the Hyphasis at Alexander’s bidding. He says : “The battle with Poros depressed the spirits of the Macedonians and made them very unwilling to advance farther into India. For, as it was with the utmost difficulty they had beaten him when the army he led amounted only to 20,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, they now most resolutely opposed Alexander when he insisted that they should cross the Ganges.” The Greeks had been impressed by the heroism and skill of Indian soldiers. Indeed, according to Arrian, “in the art of war they were far superior to the other nations by which Asia was at that time inhabited.” That is perhaps why the Greeks showed even after fighting against Poros that they had “no stomach for further toils in India.” But when Alexander egged them on to march forward it was like putting the proverbial last straw on the camel’s back. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

“During their progress towards the Hyphasis Alexander’s troops had heard all sorts of alarming rumours that beyond it there were extensive and uninviting deserts, impetuous and unfathomable rivers, and what was more disquieting, powerful and wealthy nations maintaining huge armies. Curtius represents Phegeus (Phegelis P), identified with Bhagala, as giving the following information to Alexander : “The farther bank of the Ganges was inhabited by two nations, the Gangaridae, and the Prasii, whose king Agrammes kept in the field for guarding the approaches to his country 20,000 cavalry and 200,000 infantry besides 2,000 four-horsed chariots, and what was most formidable force of all, a troop of elephants, which ran up to the number of 3,ooo”. Similarly, Plutarch says that “the kings of the Gangaritai and Praisiai were reported to be waiting for him with an army of 80,000 horse and 200,000 foot, 8,000 war-chariots and 6,000 fighting elephants. Nor was this an exaggeration, for not long afterwards Androkottos who had by that time mounted the throne, presented Seleukos with 500 elephants and overran and subdued the whole of India with an army of 600,000 men.” The substantial truth of these statements is borne out by indigenous sources also, which tell us of the enormous riches and power of the Nanda monarch holding sway over the Gangaridai and Prasii nations. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Arrian’s deposition, too, is much to the same effect, but he seems to refer to the country immediately beyond the Hyphasis. He observes : “It was exceedingly fertile, and the inhabitants were good agriculturists, brave in war, and living under an excellent system of internal government; for the multitude was governed by the aristocracy, who exercised their authority with justice and moderation. It was also reported that the people there had a greater number of elephants than the other Indians, and that those were of superior size and courage.” These details spurred the indomitable spirit of Alexander and made him all the more keen to advance into the heart of India. The Macedonians, on the other hand, as affirmed by Arrian, “now began to lose heart when they saw the king raising up without end toils upon toils and dangers upon dangers.” Indeed, the army held conferences “at which the more moderate men bewailed their condition, while others positively asserted that they would follow no farther though Alexander himself should lead the way ”.

Alexander’s Speech to the Officers

Alexander made a fervent appeal to his comrades to rumours and follow him with “alacrity and confidence.” He declared : “I am not ignorant, soldiers, that during these last days the natives of this country have been spreading all sorts of rumours designed expressly to work upon your fears, but the falsehood of those who invent such lies is nothing new in your experience ”. This assurance was, however, of no avail. The troops persisted in their refusal to enter into further contests with the Indians beyond the Beas, “whose numbers,” so answered Koinos, “though purposely exaggerated by the barbarians, must yet, as I can gather from the lying report itself, be very considerable.” Alexander made his last desperate attempt to rouse the spirit of his soldiers by threatening to march on even if forsaken by them : “Expose me then to the dangers of rivers, to the rage of elephants, and to those nations whose very names fill you with terror. I shall find men that will follow me though I be deserted by you.” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Arrian wrote: “When he heard of this, before the disorder and pusillanimity of the soldiers should advance to a great degree, be called a council of the officers of the brigades and addressed them as follows:—“O Macedonians and Grecian allies, seeing that you no longer follow me into dangerous enterprises with a resolution equal to that which formerly animated you, I have collected you together into the same spot, so that I may either persuade you to march forward with me, or may be persuaded by you to return. If indeed the labours which you have already undergone up to our present position seem to you worthy of disapprobation, and if you do not approve of my leading you into them, there can be no advantage in my speaking any further. But, if as the result of these labours, you hold possession of Ionia, the Hellespont, both the Phrygias, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Lydia, Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phoenicia, Egypt together with Grecian Libya, as well as part of Arabia, Hollow Syria, Syria between the rivers, Babylon, the nation of the Susians, Persia, Media, besides all the nations which the Persians and the Medes ruled, and many of those which they did not rule, the land beyond the Caspian Gates, the country beyond the Caucasus, the Tanais, as well as the land beyond that river, Bactria, Hyrcania, and the Hyrcanian Sea; if we have also subdued the Scythians as far as the desert; if, in addition to these, the river Indus flows through our territory, as do also the Hydaspes, the Acesines, and the Hydraotes, why do ye shrink from adding the Hyphasis also, and the nations beyond this river, to your empire of Macedonia? Do ye fear that your advance will be stopped in the future by any other barbarians? Of whom some submit to us of their own accord, and others are captured in the act of fleeing, while others, succeeding in their efforts to escape, hand over to us their deserted land, which we add to that of our allies, or to that of those who have voluntarily submitted to us.” [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“I, for my part, think, that to a brave man there is no end to labours except the labours themselves, provided they lead to glorious achievements. But if any one desires to hear what will be the end to the warfare itself, let him learn that the distance still remaining before we reach the river Ganges and the Eastern Sea is not great; and I inform you that the Hyrcanian Sea will be seen to be united with this, because the Great Sea encircles the whole earth. I will also demonstrate both to the Macedonians and to the Grecian allies, that the Indian Gulf is confluent with the Persian, and the Hyrcanian Sea with the Indian Gulf. From the Persian Gulf our expedition will sail round into Libya as far as the Pillars of Heracles. From the pillars all the interior of Libya becomes ours, and so the whole of Asia will belong to us, and the limits of our empire, in that direction, will be those which God has made also the limits of the earth. But, if we now return, many warlike nations are left unconquered beyond the Hyphasis as far as the Eastern Sea, and many besides between these and Hyrcania in the direction of the north wind, and not far from these the Scythian races. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“Wherefore, if we go back, there is reason to fear that the races which are now held in subjection, not being firm in their allegiance, may be excited to revolt by those who are not yet subdued. Then our many labours will prove to have been in vain; or it will be necessary for us to incur over again fresh labours and dangers, as at the beginning. But, O Macedonians and Grecian allies, stand firm! Glorious are the deeds of those who undergo labour and run the risk of danger; and it is delightful to live a life of valour and to die leaving behind immortal glory. Do ye not know that our ancestor reached so great a height of glory as from being a man to become a god, or to seem to become one, not by remaining in Tiryns or Argos, or even in the Peloponnese or at Thebes? The labours of Dionysus were not few, and he was too exalted a deity to be compared with Heracles. But we, indeed, have penetrated into regions beyond Nysa; and the rock of Aornus, which Heracles was unable to capture, is in our possession.

Do ye also add the parts of Asia still left unsubdued to those already acquired, the few to the many. But what great or glorious deed could we have performed, if, sitting at ease in Macedonia, we had thought it sufficient to preserve our own country without any labour, simply repelling the attacks of the nations on our frontiers, the Thracians, Illyrians, and Triballians, or even those Greeks who were unfriendly to our interests? If, indeed, without undergoing labour and being free from danger I were acting as your commander, while you were undergoing labour and incurring danger, not without reason would you be growing faint in spirit and resolution, because you alone would be sharing the labours, while procuring the rewards of them for others. But now the labours are common to you and me, we have an equal share of the dangers, and the rewards are open to the free competition of all. For the land is yours, and you act as its viceroys. The greater part also of the money now comes to you; and when we have traversed the whole of Asia, then, by Zeus, not merely having satisfied your expectations, but having even exceeded the advantages which each man hopes to receive, those of you who wish to return home I will send back to their own land, or I will myself lead them back; while those who remain here, I will make objects of envy to those who go back.”

Coenus’s Answer to Alexander

Arrian wrote: “When Alexander had uttered these remarks, and others in the same strain, a long silence ensued, for the auditors neither had the audacity to speak in opposition to the king without constraint, nor did they wish to acquiesce in his proposal. Hereupon, he repeatedly urged any one who wished it, to speak, if he entertained different views from those which he had himself expressed. Nevertheless the silence still continued a long time; but at last, Coenus, son of Polemocrates, plucked up courage and spoke as follows:[Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“I feel it incumbent upon me not to conceal what I think the best course to pursue, both on account of my age, the honour paid to me by the rest of the army at thy behest, and the boldness which I have without any hesitation displayed up to the present time in incurring dangers and undergoing labours. The more numerous and the greater the exploits have been, which were achieved by thee as our commander, and by those who started from home with thee, the more advantageous does it seem to me that some end should be put to our labours and dangers. For thou thyself seest how many Macedonians and Greeks started with thee, and how few of us have been left. Of our number thou didst well in sending back home the Thessalians at once from Bactra, because thou didst perceive that they were no longer eager to undergo labours. Of the other Greeks, some have been settled as colonists in the cities which thou hast founded; where they remain not indeed all of them of their own free will. The Macedonian soldiers and the other Greeks who still continued to share our labours and dangers, have either perished in the battles, become unfit for war on account of their wounds, or been left behind in the different parts of Asia. The majority, however, have perished from disease, so that few are left out of many; and these few are no longer equally vigorous in body, while in spirit they are much more exhausted. All those whose parents still survive, feel a great yearning to see them once more; they feel a yearning after their wives and children, and a yearning for their native land itself; which it is surely pardonable for them to yearn to see again with the honour and dignity they have acquired from thee, returning as great men, whereas they departed small, and as rich men instead of being poor.

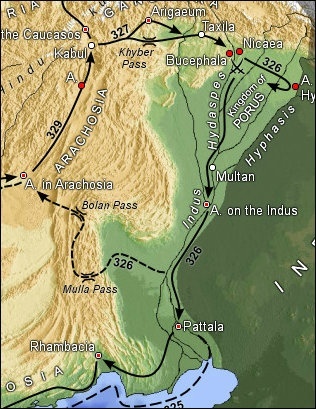

Alexander's route through Pakistan and India to the Arabian Sea

“Do not lead us now against our will; for thou wilt no longer find us the same men in regard to dangers, since free-will will be wanting to us in the contests. But, rather, if it seem good to thee, return to thy own land, see thy mother, regulate the affairs of the Greeks, and carry to the home of thy fathers these victories so many and great. Then start afresh on another expedition, if thou wishest, against these very tribes of Indians situated towards the east; or, if thou wishest, into the Euxine Sea; or else against Carchedon and the parts of Libya beyond the Carchedonians. It is now thy business to manage these matters; and the other Macedonians and Greeks will follow thee, young men in place of old, fresh men in place of exhausted ones, and men to whom warfare has no terrors, because up to the present time they have had no experience of it; and they will be eager to set out, from hope of future reward. The probability also is, that they will accompany thee with still more zeal on this account, when they see that those who in the earlier expedition shared thy labours and dangers have returned to their own abodes as rich men instead of being poor, and renowned instead of being obscure as they were before. Self-control in the midst of success is the noblest of all virtues, O king! For thou hast nothing to fear from enemies, while thou art commanding and leading such an army as this; but the visitations of the deity are unexpected, and consequently men can take no precautions against them.”

“When Coenus had concluded this speech, loud applause was given to his words by those who were present; and the fact that many even shed tears, made it still more evident that they were disinclined to incur further hazards, and that return would be delightful to them. Alexander then broke up the conference, being annoyed at the freedom of speech in which Coenus indulged, and the hesitation displayed by the other officers. But the next day he called the same men together again in wrath, and told them that he intended to advance farther, but would not force any Macedonian to accompany him against his will; that he would have those only who followed their king of their own accord; and that those who wished to return home were at liberty to return and carry back word to their relations that they were come back, having deserted their king in the midst of his enemies.

“Having said this, he retired into his tent, and did not admit any of the Companions on that day, or until the third day from that, waiting to see if any change would occur in the minds of the Macedonians and Grecian allies, as is wont to happen, as a general rule among a crowd of soldiers, rendering them more disposed to obey. But on the contrary, when there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it, Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he none the less offered sacrifice there for the passage of the river, but the victims were unfavourable to him when he sacrificed. Then indeed he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army that he had resolved to march back again.”

Preparations for a Voyage down the Indus

Alexander then made preparations for sailing down the rivers, but before the voyage actually began he cleared the path of all potential enemies by bringing about the subjugation of Sophytes (Saubhuti ?), whose kingdom had “a mountain of fossil salt which could supply all India.” He was thus the chief of the country of the Salt range. Incidentally, it may be noted that according to Strabo the land of Sophytes had dogs of “astonishing courage” and mettle, and Alexander witnessed their fight oven with a lion. Curtius further avers that the people of Sophytes “excelled in wisdom, and lived under good laws and customs.” Like the Kathaians, they held beauty in great esteem and marriages were contracted not on considerations of high birth but of looks. They examined every infant medically, and if they found “anything deformed or defective in the limbs of a child they ordered it to be killed ” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Plutarch wrote: “Alexander was now eager to see the ocean. To which purpose he caused a great many row-boats and rafts to be built, in which he fell gently down the rivers at his leisure, yet so that his navigation was neither unprofitable nor inactive. For by several descents upon the banks, he made himself master of the fortified towns, and consequently of the country on both sides.[Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Arrian wrote: “Alexander now resolved to sail down the Hydaspes to the Great Sea, after he had prepared on the banks of that river many thirty-oared galleys and others with one and a half bank of oars, as well as a number of vessels for conveying horses, and all the other things requisite for the easy conveyance of an army on a river. At first he thought he had discovered the origin of the Nile, when he saw crocodiles in the river Indus, which he had seen in no other river except the Nile, as well as beans growing near the banks of the Acesines of the same kind as those which the Egyptian land produces. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“This conjecture was confirmed when he heard that the Acesines falls into the Indus. He thought the Nile rises somewhere or other in India, and after flowing through an extensive tract of desert country loses the name of Indus there; but afterwards when it begins to flow again through the inhabited land, it is called Nile both by the Aethiopians of that district and by the Egyptians, and finally empties itself into the Inner Sea. In like manner Homer made the river Egypt give its name to the country of Egypt. Accordingly when he wrote to Olympias about the country of India, after mentioning other things, he said that he thought he had discovered the sources of the Nile, forming his conclusions about things so great from such small and trivial premisses. However, when he had made a more careful inquiry into the facts relating to the river Indus, he learned the following details from the natives:—That the Hydaspes unites its water with the Acesines, as the latter does with the Indus, and that they both yield up their names to the Indus; that the last-named river has two mouths, through which it discharges itself into the Great Sea; but that it has no connection with the Egyptian country. He then removed from the letter to his mother the part he had written about the Nile. Planning a voyage down the rivers as far as the Great Sea, he ordered ships for this purpose to be prepared for him. The crews of his ships were fully supplied from the Phoenicians, Cyprians, Carians, and Egyptians who accompanied the army.”

Indus River and it Tributaries, including Hydraotes (Ravi), Acesines (Chenab) and Hydaspes (Jhelum)

Voyage down the Hydaspes and Acesines

Towards the close of October the signal for departure was given with the sound of the trumpet, and the Macedonian boats glided down the river in grand array, protected on both the banks by troops under the command of Hephsestion and Krateros respectively, until they reached the confluence of the Acesines and the Hydaspes. The army rode down the rivers on the rivers on rafts and stopped to attack and subdue villages along the way. During this trip, Alexander sought out the Indian philosophers, the Brahmins, who were famous for their wisdom, and debated them on philosophical issues. He became legendary for centuries in India for being both a wise philosopher and a fearless conqueror. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Arrian wrote: “At this time Coenus, who was one of Alexander’s most faithful Companions, fell ill and died, and the king buried him with as much magnificence as circumstances allowed. Then collecting the Companions and the Indian envoys who had come to him, he appointed Porus king of the part of India which had already been conquered, seven nations in all, containing more than , cities. After this he made the following distribution of his army. With himself he placed on board the ships all the shield-bearing guards, the archers, the Agrianians, and the body-guard of cavalry. Craterus led a part of the infantry and cavalry along the right bank of the Hydaspes, while along the other bank Hephaestion advanced at the head of the most numerous and efficient part of the army, including the elephants, which now numbered about . [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“When he had made all the necessary preparations the army began to embark at the approach of the dawn; while according to custom he offered sacrifice to the gods and to the river Hydaspes, as the prophets directed. When he had embarked he poured a libation into the river from the prow of the ship out of a golden goblet, invoking the Acesines as well as the Hydaspes, because he had ascertained that it is the largest of all the rivers which unite with the Hydaspes, and that their confluence was not far off. He also invoked the Indus, into which the Acesines flows after its junction with the Hydaspes. Moreover he poured out libations to his forefather Heracles, to Ammon, and the other gods to whom he was in the habit of sacrificing, and then he ordered the signal for starting seawards to be given with the trumpet. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“As soon as the signal was given they commenced the voyage in regular order; for directions had been given at what distance apart it was necessary for the baggage vessels to be arranged, as also for the vessels conveying the horses and for the ships of war; so that they might not fall foul of each other by sailing down the channel at random. He did not allow even the fast-sailing ships to get out of rank by outstripping the rest. The noise of the rowing was never equalled on any other occasion, inasmuch as it proceeded from so many ships rowed at the same time; also the shouting of the boatswains giving the time for beginning and stopping the stroke of the oars, and the clamour of the rowers, when keeping time all together with the dashing of the oars, made a noise like a battle-cry.

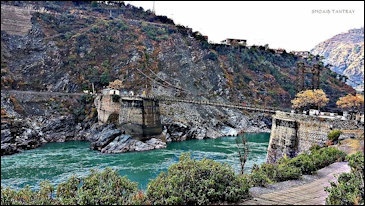

bridge over the Chenan (Acesines) river

The banks of the river also, being in many places higher than the ships, and collecting the sound into a narrow space, sent back to each other an echo which was very much increased by its very compression. In some parts too the groves of trees on each side of the river helped to swell the sound, both from the solitude and the reverberation of the noise. The horses which were visible on the decks of the transports struck the barbarians who saw them with such surprise that those of them who were present at the starting of the fleet accompanied it a long way from the place of embarkation. For horses had never before been seen on board ships in the country of India; and the natives did not call to mind that the expedition of Dionysus into India was a naval one. The shouting of the rowers and the noise of the rowing were heard by the Indians who had already submitted to Alexander, and these came running down to the river’s bank and accompanied him singing their native songs. For the Indians have been eminently fond of singing and dancing since the time of Dionysus and those who under his bacchic inspiration traversed the land of the Indians with him.”

“Then be sailed rapidly towards the country of the Mallians and Oxydracians, having ascertained that these tribes were the most numerous and the most warlike of the Indians in that region; and having been informed that they had put their wives and children for safety into their strongest cities, with the resolution of fighting a battle with him, be made the voyage with the greater speed with the express design of attacking them before they had arranged their plans, and while there was still lack of preparation and a state of confusion among them. Thence he made his second start, and on the fifth day reached the junction of the Hydaspes and Acesines. Where these rivers unite, one very narrow river is formed out of the two; and on account of its narrowness the current is swift. There are also prodigious eddies in the whirling stream, and the water rises in waves and plashes exceedingly, so that the noise of the swell of waters is distinctly heard by people while they are still far off. These things had previously been reported to Alexander by the natives, and be had told his soldiers; and yet, when his army approached the junction of the rivers, the noise made by the stream produced so great an impression upon them that the sailors stopped rowing, not from any word of command, but because the very boatswains who gave the time to the rowers became silent from astonishment and stood aghast at the noise.”

“When they came near the junction of the rivers, the pilots passed on the order that the men should row as hard as possible to get out of the narrows, so that the ships might not fall into the eddies and be overturned by them, but might by the vigorous rowing overcome the whirlings of the water. Being of a round form, the merchant vessels which happened to be whirled round by the current received no damage from the eddy, but the men who were on board were thrown into disorder and fright. For being kept upright by the force of the stream itself, these vessels settled again into the onward course.

Hydaspes (Jhelum) river

“But the ships of war, being long, did not emerge so scatheless from the whirling current, not being raised aloft in the same way as the others upon the plashing swell of water. These ships had two ranks of oars on each side, the lower oars being only a little out of the water. These vessels getting athwart in the eddies, their oars could not be raised aloft in proper time and were consequently caught by the water and came into collision with each other. Thus many of the ships were damaged; two indeed fell foul of each other and were destroyed, and many of those sailing in them perished. But when the river widened out, there the current was no longer so rapid, and the eddies did not whirl round with so much violence. Alexander therefore moored his fleet on the right bank, where there was a protection from the force of the stream and a roadstead for the ships. A certain promontory also in the river jutted out conveniently for collecting the wrecks. He preserved the lives of the men who were still being conveyed upon them; and when he had repaired the damaged ships, he ordered Nearchus to sail down the river until he reached the confines of the nation called Mallians.

Alexander Wounded in Campaign against the Mallians

The Mallians were said to be one of the most warlike of the Indian tribes. Alexander was wounded several times in this attack, most seriously when an arrow pierced his breastplate and his ribcage. The Macedonian officers rescued him in a narrow escape from the village. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Plutarch wrote: “At a siege of a town of the Mallians, who have the repute of being the bravest people of India, he ran in great danger of his life. For having beaten off the defendants with showers of arrows, he was the first man that mounted the wall by a scaling ladder, which, as soon as he was up, broke and left him almost alone, exposed to the darts which the barbarians threw at him in great numbers from below. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“In this distress, turning himself as well as he could, he leaped down in the midst of his enemies, and had the good fortune to light upon his feet. The brightness and clattering of his armor when he came to the ground, made the barbarians think they saw rays of light, or some bright phantom playing before his body, which frightened them so at first, that they ran away and dispersed. Till seeing him seconded but by two of his guards, they fell upon him hand to hand, and some, while he bravely defended himself, tried to wound him through his armor with their swords and spears. And one who stood further off, drew a bow with such just strength, that the arrow finding its way through his cuirass, stuck in his ribs under the breast. This stroke was so violent, that it made him give back, and set one knee to the ground, upon which the man ran up with his drawn scimitar, thinking to despatch him, and had done it, if Peucestes and Limnæus had not interposed, who were both wounded, Limnæus mortally, but Peucestes stood his ground, while Alexander killed the barbarian. But this did not free him from danger; for besides many other wounds, at last he received so weighty a stroke of a club upon his neck, that he was forced to lean his body against the wall, still, however, facing the enemy. At this extremity, the Macedonians made their way in and gathered round him.”

See Separate Article: LAST BATTLES OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S CAMPAIGN factsanddetails.com

Voyage down the Indus to the Land of Musicanus

Indus River

Arrian wrote: “After this the Acesines takes in the Hyphasis, and finally flows into the Indus under its own name; but after the junction it yields its name to the Indus. From this point I have no doubt that the Indus proceeds stades, and perhaps more, before it is divided so as to form the Delta; and there it spreads out more like a lake than a river.There, at the confluence of the Acesines and Indus, he waited until Perdiccas with the army arrived, after having routed on his way the independent tribe of the Abastanians. Meantime, he was joined by other thirty-oared galleys and trading vessels which had been built for him among the Xathrians, another independent tribe of Indians who had yielded to him. From the Ossadians, who were also an independent tribe of Indians, came envoys to offer the submission of their nation. Having fixed the confluence of the Acesines and Indus as the limit of Philip’s viceroyalty, he left with him all the Thracians and as many men from the infantry regiments as appeared to him sufficient to provide for the security of the country. He then ordered a city to be founded there at the very junction of the two rivers, expecting that it would become large and famous among men. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“He also ordered a dockyard to be made there. At this time the Bactrian Oxyartes, father of his wife Roxana, came to him, to whom he gave the viceroyalty over the Parapamisadians, after dismissing the former viceroy, Tiryaspes, because he was reported to be exercising his authority improperly. Then he transported Craterus with the main body of the army and the elephants to the left bank of the river Indus, both because it seemed easier for a heavy-armed force to march along that side of the river, and the tribes dwelling near were not quite friendly. He himself sailed down to the capital of the Sogdians; where he fortified another city, made another dockyard, and repaired his shattered vessels. He appointed Oxyartes viceroy, and Peithon general of the land extending from the confluence of the Indus and Acesines as far as the sea, together with all the coastland of India. He then again despatched Craterus with his army through the country of the Arachotians and Drangians; and himself sailed down the river into the dominions of Musicanus, which was reported to be the most prosperous part of India.

“He advanced against this king because he had not yet come to meet him to offer the submission of himself and his land, nor had he sent envoys to seek his alliance. He had not even sent him the gifts which were suitable for a great king, or asked any favour from him. He accelerated his voyage down the river to such a degree that he succeeded in reaching the confines of the land of Musicanus before he had even heard that Alexander had started against him. Musicanus was so greatly alarmed that he went as fast as he could to meet him, bringing with him the gifts valued most highly among the Indians, and taking all his elephants. He offered to surrender both his nation and himself, at the same time acknowledging his error, which was the most effectual way with Alexander for any one to get what he requested. Accordingly for these considerations Alexander granted him an indemnity for his offences. He also granted him the privilege of ruling the city and country, both of which Alexander admired. Craterus was directed to fortify the citadel in the capital; which was done while Alexander was still present. A garrison was also placed in it, because he thought the place suitable for keeping the circumjacent tribes in subjection.”

Indian Philosophers

Plutarch wrote: “In this voyage, he took ten of the Indian philosophers prisoners, who had been most active in persuading Sabbas to revolt, and had caused the Macedonians a great deal of trouble. These men, called Gymnosophists, were reputed to be extremely ready and succinct in their answers, which he made trial of, by putting difficult questions to them, letting them know that those whose answers were not pertinent, should be put to death, of which he made the eldest of them judge. The first being asked which he thought most numerous, the dead or the living, answered, “The living, because those who are dead are not at all.” Of the second, he desired to know whether the earth or the sea produced the largest beast; who told him, “The earth, for the sea is but a part of it.” His question to the third was, Which is the cunningest of beasts? “That,” said he, “which men have not yet found out.” He bade the fourth tell him what argument he used to Sabbas to persuade him to revolt. “No other,” said he, “than that he should either live or die nobly.” Of the fifth he asked, Which was eldest, night or day? The philosopher replied, “Day was eldest, by one day at least.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“But perceiving Alexander not well satisfied with that account, he added, that he ought not to wonder if strange questions had as strange answers made to them. Then he went on and inquired of the next, what a man should do to be exceedingly beloved. “He must be very powerful,” said he, “without making himself too much feared.” The answer of the seventh to his question, how a man might become a god, was, “By doing that which was impossible for men to do.” The eighth told him, “Life is stronger than death, because it supports so many miseries.” And the last being asked, how long he thought it decent for a man to live, said, “Till death appeared more desirable than life.” Then Alexander turned to him whom he had made judge, and commanded him to give sentence. “All that I can determine,” said he, “is, that they have every one answered worse than another.” “Nay,” said the king, “then you shall die first, for giving such a sentence.” “Not so, O king,” replied the gymnosophist, “unless you said falsely that he should die first who made the worst answer.” In conclusion he gave them presents and dismissed them.

“But to those who were in greatest reputation among them, and lived a private quiet life, he sent Onesicritus, one of Diogenes the Cynic’s disciples, desiring them to come to him. Calanus, it is said, very arrogantly and roughly commanded him to strip himself, and hear what he said, naked, otherwise he would not speak a word to him, though he came from Jupiter himself. But Dandamis received him with more civility, and hearing him discourse of Socrates, Pythagoras, and Diogenes, told him he thought them men of great parts, and to have erred in nothing so much, as in having too great respect for the laws and customs of their country. Others say, Dandamis only asked him the reason why Alexander undertook so long a journey to come into those parts. Taxiles, however, persuaded Calanus to wait upon Alexander. [243] His proper name was Sphines, but because he was wont to say Cale, which in the Indian tongue is a form of salutation, to those he met with anywhere, the Greeks called him Calanus. He is said to have shown Alexander an instructive emblem of government, which was this. He threw a dry shrivelled hide upon the ground, and trod upon the edges of it. The skin when it was pressed in one place, still rose up in another, wheresoever he trod round about it, till he set his foot in the middle, which made all the parts lie even and quiet. The meaning of this similitude being that he ought to reside most in the middle of his empire, and not spend too much time on the borders of it.”

Voyage Down the Indus Towards the Sea

Arrian wrote: “After instructing Hephaestion to fortify the citadel in Patala, he sent men into the adjacent country, which was waterless, to dig wells and to render the land fit for habitation. Certain of the native barbarians attacked these men, and falling upon them unawares slew some of them; but having lost many of their own men, they fled into the desert. The work was therefore accomplished by those who had been sent out, another army having joined them, which Alexander had despatched to take part in the work, when he heard of the attack of the barbarians. Near Patala the water of the Indus is divided into two large rivers, both of which retain the name of Indus as far as the sea. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“Here Alexander constructed a harbour and dockyard; and when his works had advanced towards completion he resolved to sail down as far as the mouth of the right branch of the river. He gave Leonnatus the command of , cavalry and , heavy and light-armed infantry, and sent him to march through the island of Patala opposite the naval expedition; while he himself took the fastest sailing vessels, having one and a half bank of oars, all the thirty-oared galleys, and some of the boats, and began to sail down the right branch of the river. The Indians of that region had fled, and consequently he could get no pilot for the voyage, and the navigation of the river was very difficult. On the day after the start a storm arose, and the wind blowing right against the stream made the river hollow and shattered the hulls of the vessels violently, so that most of his ships were injured, and some of the thirty-oared galleys were entirely broken up. But they succeeded in running them aground before they quite fell to pieces in the water; and others were therefore constructed. He then sent the quickest of the light-armed troops into the land beyond the river’s bank and captured some Indians, who from this time piloted him down the channel. But when they arrived at the place where the river expands, so that where it was widest it extended stades, a strong wind blew from the outer sea, and the oars could hardly be raised in the swell; they therefore took refuge again in a canal into which his pilots conducted them.”

Opulence of the Indian kings

“While their vessels were moored here, the phenomenon of the ebb and flow of the tide in the great sea occurred, so that their ships were left upon dry ground. This caused Alexander and his companions no small alarm, inasmuch as they were previously quite unacquainted with it. But they were much more alarmed when, the time coming round again, the water approached and the hulls of the vessels were raised aloft. The ships which it caught settled in the mud were raised aloft without any damage, and floated again without receiving any injury; but those that had been left on the drier land and had not a firm settlement, when an immense compact wave advanced, either fell foul of each other or were dashed against the land and thus shattered to pieces. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“When Alexander had repaired these vessels as well as his circumstances permitted, he sent some men on in advance down the river in two boats to explore the island at which the natives said he must moor his vessels in his voyage to the sea. They told him that the name of the island was Cilluta. As he was informed that there were harbours in this island, that it was a large one and had plenty of water in it, he made the rest of his fleet put in there; but he himself with the best sailing ships advanced beyond, to see if the mouth of the river afforded an easy voyage out into the open sea. After advancing about stades from the first island, they descried another which was quite out in the sea. Then indeed they returned to the island in the river; and having moored his vessels near the extremity of it, Alexander offered sacrifice to those gods to whom he said he had been directed by Ammon to sacrifice. On the following day he sailed down to the other island which was in the deep sea; and having come to shore here also, he offered other sacrifices to other gods and in another manner. These sacrifices he also offered according to the oracular instructions of Ammon. Then having gone beyond the mouths of the river Indus, he sailed out into the open sea, as he said, to discover if any land lay anywhere near in the sea; but in my opinion, chiefly that he might be able to say that he had navigated the great outer sea of India. There he sacrificed some bulls to Poseidon and cast them into the sea; and having poured out a libation after the sacrifice, he threw the goblet and bowls, which were golden, into the deep as thank-offerings, praying the god to escort safely for him the fleet, which he intended to despatch to the Persian Gulf and the mouths of the Euphrates and Tigres.”

Exploration of the Mouths of the Indus

Arrian wrote: “Returning to Patala, he found that the citadel had been fortified and that Peithon had arrived with his army, having accomplished everything for which he was despatched. He ordered Hephaestion to prepare what was needful for the fortification of a naval station and the construction of dockyards; for he resolved to leave behind here a fleet of many ships near the city of Patala, where the river Indus divides itself into two streams. He himself sailed down again into the Great Sea by the other mouth of the Indus, to ascertain which branch of the river is easier to navigate. The mouths of the river Indus are about stades distant from each other. In the voyage down he arrived at a large lake in the mouth of the river, which the river makes by spreading itself out; or perhaps the waters of the surrounding district draining into it make it large, so that it very much resembles a gulf of the sea. For in it were seen fish like those in the sea, larger indeed than those in our sea. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“Having moored his ships then in this lake, where the pilots directed, he left there most of the soldiers and all the boats with Leonnatus; but he himself with the thirty-oared galleys and the vessels with one and a half row of oars passed beyond the mouth of the Indus, and advancing into the sea also this way, ascertained that the outlet of the river on this side (i.e. the west) was easier to navigate than the other. He moored his ships near the shore, and taking with him some of the cavalry went along the sea-coast three days’ journey, exploring what kind of country it was for a coasting voyage, and ordering wells to be dug, so that the sailors might have water to drink. He then returned to the ships and sailed back to Patala; but he sent a part of his army along the sea-coast to effect the same thing, instructing them to return to Patala when they had dug the wells. Sailing again down to the lake, he there constructed another harbour and dockyard; and leaving a garrison for the place, he collected sufficient food to supply the army for four months, as well as whatever else he could procure for the coasting voyage.”

Alexander the Great Reaches the Arabian Sea

Indus River Delta

Plutarch wrote: “His voyage down the rivers took up seven months’ time, and when he came to the sea, he sailed to an island which he himself called Scillustis, others Psiltucis, where going ashore, he sacrificed, and made what observations he could as to the nature of the sea and the sea-coast. Then having besought the gods that no other man might ever go beyond the bounds of this expedition, he ordered his fleet, of which he made Nearchus admiral, and Onesicritus pilot, to sail round about, keeping the Indian shore on the right hand, and returned himself by land through the country of the Orites, where he was reduced to great straits for want of provisions, and lost a vast number of men, so that of an army of one hundred and twenty thousand foot and fifteen thousand horse, he scarcely brought back above a fourth part out of India, they were so diminished by diseases, ill diet, and the scorching heats, but most by famine. For their march was through an uncultivated country whose inhabitants fared hardly, possessing only a few sheep, and those of a wretched kind, whose flesh was rank and unsavory, by their continual feeding upon sea-fish. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“After sixty days march he came into Gedrosia, where [244] he found great plenty of all things, which the neighboring kings and governors of provinces, hearing of his approach, had taken care to provide. When he had here refreshed his army, he continued his march through Carmania, feasting all the way for seven days together. He with his most intimate friends banqueted and revelled night and day upon a platform erected on a lofty, conspicuous scaffold, which was slowly drawn by eight horses. This was followed by a great many chariots, some covered with purple and embroidered canopies, and some with green boughs, which were continually supplied afresh, and in them the rest of his friends and commanders drinking, and crowned with garlands of flowers. Here was now no target or helmet or spear to be seen; instead of armor, the soldiers handled nothing but cups and goblets and Thericlean drinking vessels, which, along the whole way, they dipped into large bowls and jars, and drank healths to one another, some seating themselves to it, others as they went along.

All places resounded with music of pipes and flutes, with harping and singing, and women dancing as in the rites of Bacchus. For this disorderly, wandering march, besides the drinking part of it, was accompanied with all the sportiveness and insolence of bacchanals, as much as if the god himself had been there to countenance and lead the procession. As soon as he came to the royal palace of Gedrosia, he again refreshed and feasted his army; and one day after he had drunk pretty hard, it is said, he went to see a prize of dancing contended for, in which his favorite Bagoas, having gained the victory, crossed the theatre in his dancing habit, and sat down close by him, which so pleased the Macedonians, that they made loud acclamations for him to kiss Bagoas, and never stopped clapping their hands and shouting till Alexander put his arms round him and kissed him.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, " Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024