ALEXANDER THE GREAT IN PAKISTAN-INDIA

Alexander and Bucephalus

Alexander the Great entered the borders of India in 327 B.C. with his Macedonian army to conquer India, which before that time had been known to the Greeks by mainly often fantastic reports from the 5th century Greek historian Herodotus. The Macedonians found India and the Indians to be far less supernatural than they had been led to expect, although the land was very wealthy and the people ready for war. Despite some victories and a favorable alliance with the powerful king, Poros, India was where formerly undefeated Macedonians stopped and turned around. [Source: Glorious India ]

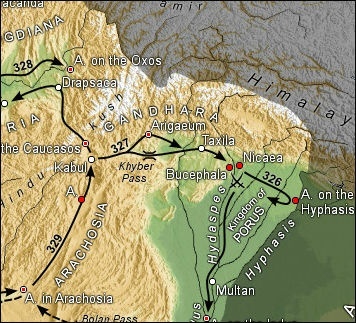

After the death of Spitamenes and his marriage to Roxana to cement relations with the Central Asian new satrapies of the Old Persian Empire, Alexander turned his attention to the Indian subcontinent. In 330-325 B.C., Alexander the Great armies marched though present-day Afghanistan, crossed the Indus and entered India briefly before following the Indus across Pakistan to the Arabian Sea and then made their way back to the Middle East. In 325 B.C. what is now the Punjab and Sind area of Pakistan and India were conquered by Alexander and became the easternmost region of his brief empire. He marched across the Salt Range south of Taxila to the Beas River from where he sailed down the Indus River to the sea and then marched across the Makaran desert and Baluchistan to Baghdad.

According to PBS: Alexander sent his main army through the Khyber Pass, and brought the rest himself on a more northerly route. He met with resistance and battles from some local rulers, while others feared his reputation and met him with gifts and supplies. His expedition reached its most easterly point in September 326 B.C. at the Beas river in the Punjab when his army — now weary of long years spent on the march—came close to mutiny. Alexander then turned back heading southwards down the Indus to the sea, fighting and besieging Indian cities all the way. There he divided his men again, sending a fleet from the mouth of the Indus back to the Persian Gulf, dispatching one army corps over the Bolan Pass, and taking the rest along the inhospitable Makran coast into Iran and back to Babylon. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

Alexander was in India east of the Indus for a brief period of about nineteen months from the spring of 326 B.C. to September 325 B.C.He was mostly busy fighting, and he could not, therefore, get time enough to consolidate his conquests. Alexander would have pushed further into the subcontinent beyond the Punjab but in 325 B.C. his weary troops, fearful of the rumors of the strong king of Magadha, mutinied on the bank of the river Hyphasis. The Macedonian king was forced to return west with India largely unconquered.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356 TO 324 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S LEADERSHIP, TACTICS, ARMY, GENERALS AND MILITARY SKILLS europe.factsanddetails.com

ALEXANDER THE GREAT DEFEATS THE PERSIANS AT GAUGAMELA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S BATTLE WITH PORUS AND WHAT THE GREEKS LEFT BEHIND IN INDIA factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT HALTS HIS CAMPAIGN AND HEADS DOWN THE INDUS TO THE ARABIAN SEA factsanddetails.com

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“On Alexander's Track to the Indus: Personal Narrative of Explorations on the North-West Frontier of India” by Aurel Stein (1862-1943) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great in India” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

"Invasion of India by Alexander the Great" by J.W. M'Crindle M'Crindle | Mar 6, 2025 Amazon.com;

“Mighty Porus and Alexander The Great: The Clash of Two Giants” (2020)

by Biren Trivedi (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Hellenistic Far East: Archaeology, Language, and Identity in Greek Central Asia”

by Rachel Mairs (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Hydaspes 326 BC: The Limit of Alexander the Great’s Conquests”

by Nic Fields and Marco Capparoni (2023) Amazon.com;

“In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great” by Michael Wood (1997) Amazon.com;

“Conquest and Empire” by A. B Bosworth (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Generalship of Alexander the Great” by J. F. C. Fuller (1958) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great at War: His Army — His Battles — His Enemies” by Ruth Sheppard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Field Campaigns of Alexander the Great” by Stephen English Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army” by Donald W. Engels (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Army of Alexander the Great” (Men at Arms Series), Illustrated, by Nicholas Sekunda (1992) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Primary Sources:(Also available for free at MIT Classics, Gutenberg.org and other Internet sources):

“History of Alexander” by Quintus Curtius Rufus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica” by Arrian (Oxford World Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander” by Arrian Amazon.com;

“The Life of Alexander the Great” by Plutarch (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

Alexander the Great’s Campaign Before India

In 327–325 B.C., Alexander the Great invaded the province of Gandhara in what is now eastern Pakistan and northwest India that had been a part of the Persian empire. After conquering Anatolia (334-3 B.C.), Phoenicia, Egypt and Libya (333-2 B.C.) and finally Persia (331-330 B.C.), Alexander the Great set his sights on the lands in northern India conquered by Darius I of Persia 200 years earlier.

After Central Asia, Alexander then headed into present-day Pakistan because he wanted to add India to his empire. His army of 75,000 men (plus a retinue of perhaps 40,000 more people), now included Persian horseman and many subjects of other conquered kingdoms but only 15,000 Macedonians. With the Persians gone, Pakistan fell under the under the control of local rulers, none of whom dared to challenge Alexander. His army was able to advance easily and he was given a warm welcome in Taxila. The local ruler there gave him a generous tribute and provided him with fresh soldiers.

In the mountains areas of Central Asia and present-day Pakistan, Alexanders' armies met fierce resistance from the Dogdians (also known as the Sogdians) and their allies the Masagates (a Saka clan), who retreated to the mountainous areas of the kingdoms and waged guerilla war that halted Alexander’s progress for 18 months. In the Karakorum range, Alexander's men used pitons and ropes to assault a supposedly impregnable fortress built into the side of a cliff by the Dogdians at the Rock of Aornos near modern Pir Sar. The soldiers in the fortress had the previous day laughed: "No one can touch us." When Alexander's force had taken their positions he said: "Come see my flying soldiers." The Dogdians in the fortress eventually surrendered and Alexander claimed Roxanne, the daughter of a nobleman, for his wife. Roxanne was reportedly around 12 and Alexander was reportedly quite taken by her beauty. The Rock of Aornos is believed to somewhere in the Hissar mountains but its exact location is unknown.

Before Alexander: Persians Conquest of Western India and Pakistan

According to PBS: “Darius I of Persia annexed the states of Sind and Punjab in northern India in 518 B.C. From then the people of the Indus valley ("Hindush" in Persian) paid tribute to the Persian king in textiles and precious local resources. After Alexander the Great overthrew the Persians and conquered the region in 326 B.C., Greek culture would be a major influence for over three hundred years, with Indo-Greek kingdoms founded in the North West Frontier, Afghanistan and the Punjab. But because of the close relation between Old Persian and Sanskrit, the influence of Persian language and culture in the northwest of the subcontinent never really waned until the collapse of the Persian-speaking Mughal Empire in the 19th century. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

In the latter half of the 6th century B.C. the north-western part of India was divided into a number of petty principalities, and there was no great power to curb their mutual strifes and jealousies. Naturally it provided a strong tempting ground to the Imperialism of the Achaemenian monarchy, which „ had arisen in Persia about this time under the leadership of Kurush or Cyrus (e. 558-30 B.C.) He extended the bounds of his empire as far west as the Mediterranean, and in the east he conquered Bactria and Gadara (Gandhara), but it is unlikely he advanced beyond the frontiers of India. His immediate successors, Kambujiya I (Cambyses I), Kurush II (Cyrus II), Kambujiya II (Cambyses II) — 530-22 B.C., — were too busy with affairs in the west to think of the east, but Darius I Darayavaush or Darius I (522-486 B.C.) appears to have annexed a portion of the Indus region, as evidenced by the inscriptions at Persepolis and on his tomb at Naksh-iRustam, mentioning the Hidus or the people of Sindhu (Indus) among Persian subjects. This conquest was made probably some time after 518 B.C., the assumed date of the Behistun record, which omits the Hidus (Indians) from the list of subject peoples, and long before 486 B.C., when Darius I died. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Herodotus tells us how Darius I essayed to achieve his object. He first sent an expedition some time after 517 B.C. under Skylax of Karyanda to explore the possibility of a passage by sea from the mouths of the Indus to Persia. He sailed down the Indus, and in the course of his voyage collected a good deal of information, afterwards utilised with advantage by Darius I. Herodotus also testifies that the conquered Indian territories, which perhaps did not include much of the Punjab, were constituted into the twentieth Satrapy of the Persian Empire; and it yielded the enormous tribute of 360 Euboic talents of gold dust, equal to about one million sterling. Obviously, these tracts were then very fertile, populated, and prosperous.

In the reign of Khshayarsha or Xerxes (486-65 B.C.), the successor of Darius I, Indian mercenaries, “clad in cotton” and bearing “cane bows and arrows tipped with iron,” formed a part of his expeditionary force against Hellas, and so it is certain that he maintained Persian authority intact in the north-western part of India. Presumably it continued for some time more, but we do not know with certitude when the connection between Persia and India finally snapped. There is, at any rate, some evidence to show that Indian auxiliaries figured in the army of Darius III Kodomannos in his fight with Alexander.

Persians in the Indian Subcontinent

By the end of the sixth century B.C., India's northwest was integrated into the Persian Achaemenid Empire and became one of its satrapies. This integration marked the beginning of administrative contacts between Central Asia and India. Much of what is now present-day Afghanistan and most of Pakistan was ruled by the Persian Achaemenid Empire from 520 B.C. during the reign of Darius I. The region of present-day Punjab, the Indus River from the borders of Gandhara down to the Arabian Sea, and some other parts of the Indus plain, became part of the empire later. [Source: Library of Congress, Glorious India ]

Gandhara and Taxila in Punjab region became part of the Achaemenid empire in 518 B.C. During this time, Pushkarasakti was the king of Gandhara. The upper Indus region, comprising regions of Gandhara and Kamboja became the seventh satrapy and the lower and middle Indus comprising Sindh and Sauvira became the 20th satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. This area was the most fertile and populous satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.

The political contact between the two countries was beneficial to both in several respects. Trade received a fillip, and perhaps the spectacle of a unified empire stirred Indian ambition to strive after a similar end. Persian scribes introduced into India the Armaic form of writing, which in Indian environments later developed into Kharosthi, written from right to left like Arabic. Scholars have even traced Persian influences in Candragupta Maurya’s court ceremonial, and in certain words and the preamble of the edicts and in the monuments, particularly the bell-shaped capitals, of Ashoka’s time.

During the Achaemenid rule, a system of centralized administration with a bureaucratic system was introduced in the region. Famous scholars such as Pan.ini and Kautilya lived during this period. Indus Valley people were recruited to the Persian army and during the rule of Achaemenid emperor Xerxes, they took part in wars against the Greeks. Achaemenid rule lasted about 186 years. By about 380 B.C., the Persian hold on the region was weakening, but the region continued to be a part of the Achaemenid Empire until it was conquered by Alexander.

The Achaemenids used the Aramaic script for the Persian language. After the end of Achaemenid rule, the use of Aramaic in the Indus plain diminished, although we know from inscriptions from the time of Emperor Asoka that it was still in use two centuries later. Other scripts, such as Kharosthi (a script derived from Aramaic) and Greek became more common after the arrival of Alexander.

India at the Time of Alexander’s Conquests

Alexander's route in present-day Pakistan

When Alexander the Great invaded the Indus Valley of Pakistan-India, the South Asian subcontinent had a population of about 30 million, of whom about 20 million lived in the Ganges Basin. One remarkable feature of India at that time was the abundance of towns, such as Massaga, Aornos, Taxila, 37 Glausai towns, Pimprama, Sangala, Pattala, etc., which testified to the material prosperity of the country. Their construction, location, and fortifications give us some idea of the system of town-planning too, then in vogue. Besides these towns, the material progress of the people was reflected in the presents received by Alexander in the course of his campaign. Thus, the envoys of the Oxydrakai, clad in purple and gold, are said to have brought for him a large quantity of cotton goods, tortoise shells, bucklers of ox-hide, and “100 talents of steel;” and Amblii of Taxila presented to Alexander “280 talents of silver and golden crowns.” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

North-western India was then, as now, famous for its fine breed of oxen, of which Alexander captured 2.30.000 from the Aspasians and sent them to Macedonia for use in agriculture. He further welcomed a gift of 3.000 “fat oxen” and 10,000 sheep from Ambhi. Evidently, agriculture and cattle-breeding were important occupations of the people in the Punjab and the North-west. Carpenters supplied chariots for the army and carts and other vehicles for trade and traffic. Judging from the existence of several rivers in the Punjab, boat and shipbuilding was perhaps a prosperous industry. It is known that Alexander used a flotilla of boats for crossing the Hydaspes and a part of his troops sailed down the Indus and one may reasonably suppose that for this fleet the invader must have utilized native labour and materials.

The Greek writers yield us some interesting information on the social customs and religious beliefs of the people of those times. For instance, we learn that beauty was so highly appreciated in the kingdom of Sangala that if any child was born defective or deformed he was killed and not allowed to grow. A handsome person was a better passport to marriage than nobility of birth. Among some tribes women observed the custom of Sati, where widows burnt themselves on their husbands funeral pyre. In Taxila the Greeks noted the strange custom of poor parents putting up girls for sale in the market-place, and further we are told that the dead were left to be devoured by vultures. Polygamy was another common practice among the people there. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Despite the prevalence of many unusual customs, Brahmanism appears to have been the dominant religion in that part of India, and Alexander’s historians narrate some unusual practices of Brahmanical ascetics like Mandanis and Kalanos (Kalyana). The Hindus commanded great respect by their learning, lofty conduct, and spirit of self-abnegation; and kings, like Mousikanos, were ready to follow their lead and direction even in political matters. Next, there were the Sarmanes or Sramanas, Buddhist and non-Buddhist recluses, who wore the bark of trees and lived in forests on wild fruits and roots. The river Ganges was then also, as now, venerated, and certain trees were held so sacred that their defilement was considered a capital offence.

Alexander the Great Prepares to Attack India

Before Alexander enter India, he felt it was necessary to reduce the force that he lead through Persia and Central Asia to accommodate the different climate and terrain. He burned all of the baggage wagons of Persian booty slowed him down, and dismissed a large number of his soldiers, reshaping his army with several thousand Persian cavalrymen. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Plutarch wrote: “Alexander now intent upon his expedition into India, took notice that his soldiers were so charged with booty that it hindered their marching. Therefore, at break of day, as soon as the baggage waggons were laden, first he set fire to his own, and to those of his friends, and then commanded those to be burnt which belonged to the rest of the army. An act which in the deliberation of it had seemed more dangerous and difficult than it proved in the execution, with which few were dissatisfied; for most of the soldiers, as if they had been inspired, uttering loud outcries and warlike shoutings, supplied one another with what was absolutely necessary, and burnt and destroyed all that was superfluous, the sight of which redoubled Alexander’s zeal and eagerness for his design. And, indeed, he was now grown very severe and inexorable in punishing those who committed any fault. For he put Menander, one of his friends, to death, for deserting a fortress where he had placed him in garrison, and shot Orsodates, one of the barbarians who revolted from him, with his own hand. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“At this time a sheep happened to yean a lamb, with the perfect shape and color of a tiara upon the head, and testicles on each side; which portent Alexander regarded with such dislike, that he immediately caused his Babylonian priests, whom he usually carried about with him for such purposes, to purify him, and told his friends he was not so much concerned for his own sake as for theirs, out of an apprehension that after his death the divine power might suffer his empire to fall into the hands of some degenerate, impotent person. But this fear was soon removed by a wonderful thing that happened not long after, and was thought to presage better.

“For Proxenus, a Macedonian, who was the chief of those who looked to the king’s furniture, as he was breaking up the ground near the river Oxus, to set up the royal pavilion, discovered a spring of a fat, oily liquor, which after the top was taken off, ran pure, clear oil, without any difference either of taste or smell, having exactly the same smoothness and brightness, and that, too, in a country where no olives grew. The water, indeed, of the river Oxus, is said to be the smoothest to the feeling of all waters, and to leave a gloss on the skins of those who bathe themselves in it. Whatever might be the cause, certain it is that Alexander was wonderfully pleased with it, as appears by his letters to Antipater, where he speaks of it as one of the most remarkable presages that God had ever favored him with. The diviners told him it signified his expedition would be glorious in the event, but very painful, and attended with many difficulties; for oil, they said, was bestowed on mankind by God as a refreshment of their labors.”

Alexander the Great in Pakistan

Taxila

After Central Asia, Alexander then headed into present-day Pakistan because he wanted to add India to his empire. His army of 75,000 men (plus a retinue of perhaps 40,000 more people), now included Persian horseman and many subjects of other conquered kingdoms but only 15,000 Macedonians. With the Persians gone, Pakistan fell under the under the control of local rulers, none of whom dared to challenge Alexander. His army was able to advance easily and he was given a warm welcome in Taxila. The local ruler there gave him a generous tribute and provided him with fresh soldiers.

Between May 327 and March 326 B.C., Alexander carried out Cophen Campaign in what is now the Swat valley and the Punjab region in Pakistan. Alexander's goal was to secure his line of communications so that he could conduct a campaign in India proper. To achieve this, he needed to capture a number of fortresses controlled by the local tribes. Cophen was the name of a river.

Arrian wrote: “After performing this exploit, Alexander himself went to Bactra; but sent Craterus with of the cavalry Companions and his own brigade of infantry as well those of Polysperchon, Attalus, and Alcetas, against Catanes and Austanes, who were the only rebels still remaining in the land of the Paraetacenians. A sharp battle was fought with them, in which Craterus was victorious; Catanes being killed there while fighting, and Austanes being captured and brought to Alexander. Of the barbarians with them horsemen and about , foot soldiers were killed. When Craterus had done this, he also went to Bactra, where the tragedy in reference to Callisthenes and the pages befell Alexander. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“As the spring was now over, he took the army and advanced from Bactra towards India, leaving Amyntas in the land of the Bactrians with , horse, and , foot. He crossed the Caucasus in ten days and arrived at the city of Alexandria, which had been founded in the land of the Parapamisadae when he made his first expedition to Bactra. He dismissed from office the governor whom he had then placed over the city, because be thought he was not ruling well. He also settled in Alexandria others from the neighbouring tribes and the soldiers who were now unfit for service in addition to the first settlers, and commanded Nicanor, one of the Companions, to regulate the affairs of the city itself. Moreover he appointed Tyriaspes viceroy of the land of the Parapamisadae and of the rest of the country as far as the river Cophen. Arriving at the city of Nicaea, he offered sacrifice to Athena and then advanced towards the Cophen, sending a herald forward to Taxiles and the other chiefs on this side the river Indus, to bid them come and meet him as each might find it convenient.

The Kafir-Kalash, a tribe that lives today in valleys off the Chistral Valley in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan, claim to be descendants of five of Alexander the Great's warriors. The tribe is famous for its their pagan beliefs, lewd songs, provocative dances, partying ways and strange costumes. The women wear black robes, red bead necklaces and cowrie-shell head-dresses. The Kalash have Caucasian features — sometimes with blonde hair and blue eyes — which gives some credence to their claim they descended from five warriors in Alexander the Great's army. There are only about 4,000 of them and they have remained pagans despite the fact that everyone around them is Muslim. The Kalash relate a story of Alexander's bacchanal with mountain dwellers claiming descent from Dionysus. They worship a pantheon of gods, make wine, and practice animal sacrifice. Although Alexander’s armies passed through the Chitral region there is little evidence that they reached the remote valleys where the Kalash live today. Other tribes in Pakistan and Central Asia also claim to be descendants of Alexander’s army.

Alexander the Great's Warm Welcome in Taxila and Battles in What Is Now Pakistan

Alexander the Great invited the chieftains of the former Persians satrapy of Gandhara (a region presently straddling eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan) to join him and submit to his authority. Omphis (Indian name Ambhi), the ruler of Taxila, whose kingdom extended from the Indus to the Hydaspes (Jhelum), complied. Alexander the Great was welcomed at Taxila by Omphis, son of the deceased Taxiles, with rich and attractive presents, consisting of silver and sheep and oxen of a good breed, and placed himself and all his forces at Alexander's disposal. Alexander not only returned Ambhi his title and the gifts but he also presented him with a wardrobe of "Persian robes, gold and silver ornaments, 30 horses and 1,000 talents in gold". Alexander thus won not only the loyalty of the ruler of Taxila but also a contingent of 5,000 soldiers from him. [Sources: Wikipedia, “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

While Omphis (Ambhi), complied with Alexander the chieftains of some hill clans, including the Aspasioi and Assakenoi sections of the Kambojas (known in Indian texts also as Ashvayanas and Ashvakayanas), refused to submit. North-western India was parcelled out into a number of states, monarchies as well as clan oligarchies, engaged in petty internecine feuds and jealousies, in which some of them found their opportunity for seeking alliance with an alien aggressor. Indeed, the gates of India were, so to say, unbarred by the Raja of Taxila, who lost no time in proffering allegiance to Alexander , and who also rendered every assistance to the advance body of the Macedonians under Perdiccas in bridging the Indus and in securing the submission of the tribes and chieftains, like Astes (Hasti or Astakaraja ?), whose territories lay on their route. [Sources: Wikipedia, “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The Aspasians of the Alisang-Kunar valley were the first to be subdued by Alexander, who captured 40,000 men and 230,000 oxen transporting the choicest among the latter to Macedonia for being employed in agriculture. Arrian (IV, 25), however, deposes that with these people “the conflict was sharp, not only from the difficult nature of the ground, but also because the Indians were.... by far the stoutest warriors in that neighbourhood.”

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S BATTLES IN WHAT IS NOW PAKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024