MOHENJO-DARO

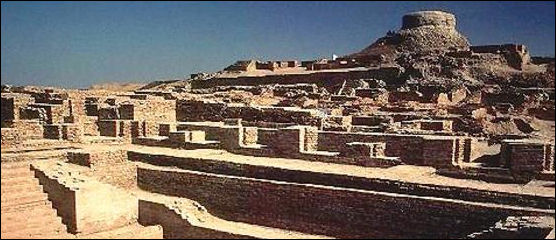

Mohenjo-Daro (560 kilometers from Karachi) was the center of an ancient Indus Valley civilization, and perhaps its capital. Likely the largest and most populous of several wealthy cities in the Indus Valley, Mohenjo-Daro covered about two square miles, only a small potion of which has been excavated. A man-made, plateau-like hill, known as the citadel, was on one side of the city. About 300 structures have been excavated there.

Mohenjo-Daro (also spelled Moenjodaro) means "Mound of the Dead." Founded perhaps 6000 years ago, Mohenjo-Daro flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. along the banks of the Indus River when the climate wasn't as harsh as it is today. Only Egypt can lay claim to a civilization that was as old and as large. At its height Mohenjo-Daro was home to maybe 80,000 people.

Discovered in 1922, Mohenjo-Daro is located in Sindh province in Pakistan. It was once a metropolis of great importance, forming the heart of the Indus Valley Civilization with Harappa (discovered in 1923 in the southern Punjab), Kot Diji (Sindh) and recently discovered Mehrgarh (Balochistan). Mohenjo-Daro is considered as one of the most important ancient cities of the ancient world. It had mud and baked bricks’ buildings, an elaborate covered drainage system, a large state granary, a spacious pillared hall, a College of Priests, a palace and a citadel. The plateau-like citadel is believed to be have been the place where the rulers of the kingdom lived. The common people lived in the flatlands.

Mohenjo-Daro is about an hour and 20 minute flight from Karachi. Situated among grain fields and semi-desert, it is not as impressive as Egypt's ancient cities. Mainly what you see are walls, fortifications and foundations; you do get a sense, however, of the place as a city with streets and blocks; shops located in one neighborhoods; houses and recreational facilities in another; and an elaborate fortress protecting the whole metropolis. Among the structures and features were pits used as disposal bins; imposing buildings; probably a palace; a citadel mound which incorporates a system of solid fired brick towers.

The landscape surrounding Mohenjo-Daro is dry and dusty, and about the only thing growing are tamarisk bushes. At its city’s height 4,500 years ago fields grew wheat, barley, peas and sesamum. Starting about 1700 B.C. the city was gradually abandoned. Nobody is sure exactly why but most archeologist speculate it was due to climatic changes or flooding that caused the Indus River to shift. The river is now five kilometers away.

Websites: Mohenjo-Daro: Complete Guide to the Indus Valley civilization (Mohenjo-Daro.org); International Campaign for Mohenjo-Daro (UNESCO Division of the Physical Heritage); Videos: Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro (UNESCO/NHK), NHK World Heritage 100 Series

Mohenjo-Daro: UNESCO World Heritage Site

Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980. According to UNESCO: The ruins of the huge city of Mohenjo-Daro – built entirely of unbaked brick in the 3rd millennium B.C. – lie in the Indus valley. The acropolis, set on high embankments, the ramparts, and the lower town, which is laid out according to strict rules, provide evidence of an early system of town planning. [Source: UNESCO]

The Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro are the best preserved urban settlement in South Asia dating back to the beginning of the 3rd millennium B.C., and exercised a considerable influence on the subsequent development of urbanization. The archaeological ruins are located on the right bank of the Indus River, 510 km north-east from Karachi, and 28 km from Larkana city, Larkana District in Pakistan’s Sindh Province. The property represents the metropolis of Indus civilization, which flourished between 2,500-1,500 B.C. in the Indus valley and is one of the world’s three great ancient civilizations.

The discovery of Mohenjo-Daro in 1922 revealed evidence of the customs, art, religion and administrative abilities of its inhabitants. The well planned city mostly built with baked bricks and having public baths; a college of priests; an elaborate drainage system; wells, soak pits for disposal of sewage, and a large granary, bears testimony that it was a metropolis of great importance, enjoying a well organized civic, economic, social and cultural system.

Mohenjo-Daro comprises two sectors: a citadel area in the west where the Buddhist stupa was constructed with unbaked brick over the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro in the 2nd century AD, and to the east, the lower city ruins spread out along the banks of the Indus. Here buildings are laid out along streets intersecting each other at right angles, in a highly orderly form of city planning that also incorporated systems of sanitation and drainage.

The site is important because: Criterion 1) The Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro comprise the most ancient planned city on the Indian subcontinent, and exerted great influence on the subsequent urbanization of human settlement in the Indian peninsular. 2) As the most ancient and best preserved urban ruin in the Indus Valley dating back to the 3rd millennium B.C., Mohenjo-Daro bears exceptional testimony to the Indus civilization.

Layout and Construction at Mohenjo-Daro

Mohenjo-Daro city boasted wide streets, more than 60 deep wells, strong foundations, and impressive walls, 40 kilometers of which have been excavated thus far. Overlooking the settlement, on the northwest end, was a highwalled platform that archaeologists dubbed a “citadel.” The citadel, built on a massive platform of mud brick, is composed of the ruins of several major structures - Great Bath, Great Granary, College Square and Pillared Hall - as well as a number of private homes. The extensive lower city is a complex of private and public houses, wells, shops and commercial buildings. These buildings are laid out along streets intersecting each other at right angles, in a highly orderly form of city planning that also incorporated important systems of sanitation and drainage.

The citadel is built almost entirely of baked brick. The acropolis, set out on high embankments while the lower town is set out on a grid system and shows sophisticated urban planning. Washing and drainage facilities were provided in all the houses, using an efficient system of collection of waste water. A wealth of ornaments, terracotta figurines, the carved and engraved steatite seals for which this civilization was famous, and other items such as the King Priest were unearthed. They tell us about the way of life, trade networks and the artistic abilities of the people. The script inscribed on the Indus Valley seals has remained undecipherable to date..

The urban planning at Mohenjo-Daro was pragmatic and at a high level. Its main thoroughfares were some 91 meters wide and were crossed by straight streets that formed blocks 364 meters in length and 182 to 273 meters in width. The city’s mud-brick walls and baked brick houses were designed to ensure the safety of its occupants so that in times of earthquakes the structures collapse outwards. It had an elaborate covered drainage system, soak pits for disposal bins, a state granary, a large and imposing building that could have been a palace and a citadel mound with solid burnt-brick towers on its margin.

Between the main streets are lanes that vary in width from about 1.5 to 3 meters. A number of small reenforced building have been excavated that some have speculated may have been policeman’s post or places for night watchmen. Water was provided by wells. which stand above ground today and look like chimneys. There is some evidence of plastering. Many houses had stairs which indicate a second story. Bathrooms were common and some had seated latrines liked those used in the West.

One of the most remarkable features of the city is its system of brick covered drains that were a precursor to a modern sanitation, an idea that didn't really take hold until 4000 years later in the West as a way to stem cholera outbreaks during the Industrial Revolution. Some of the drains lead to brick-soil tanks and large jars which acted as septic tanks. To make it easy for ancient sewer workers to climb in the drains and periodically clean them out the system was outfitted with manhole covers that were located at regular intervals. Earthenware pipes ran from the houses to main drains that ran along the streets.

Mohenjodaro

Buildings at Mohenjo-Daro

The citadel is a man-made plateau-like hill, believed to be have been the place where the rulers of the kingdom lived. The common people lived in the flatlands. Hearths and bathrooms are found in nearly every dwelling. Private wells have been discovered in some of the large houses. A Buddhist-era stupa, dating to the A.D. 2nd century is being restored. Some of the structures are threatened by the rising water table.

Judging from the remains, the Great Hall was probably the most striking of its structures, comprising an open quadrangle with verandahs of four sides’ galleries and rooms at the back, a number of halls, and a large bathing pool perhaps used for religious or ceremonial bathing. One of the largest edifices on the site, a 150 x 75 foot structure, is believed to have been a granary that stored grain during the winter time. Another large building nearby housed 27 large brick kilns. Other important building include an Assembly Hall, more kilns used for firing bricks and pottery, and a college for priests. Inside the Assembly Hall archeologist found a series of large stone rings and a statue of seated male, which has led some to believe the building was a temple.

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “ To the southeast of the citadel is the lower town, a sprawling collection of boxy, earth-colored houses whose homogeneity baffled early excavators. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who excavated at Mohenjo-Daro in the 1940s, despaired at the “miles of brickwork which alone have descended to us,” which he described as “monotonous.” In fact, these walls were likely the foundations of the mudbrick houses built above them. Based on limited evidence, such as postholes and charcoal left from roof beams, some later archaeologists envisioned a city gaily decorated with painted wood and colorful cloth. Much of this vision, however, is guesswork.” [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

Mohenjo-Daro Compounds and What They Say About the Site

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: Massimo Vidale, an Italian archaeologist based in Rome who is familiar with the site, “has pinpointed several palace-like compounds at the site. Each of these resembles a miniature citadel, and as they grew, he says, their elite owners competed for status and recognition by enlarging and beautifying their homes. One palace contains 136 rooms and is 300 feet long, with a carefully paved brick courtyard nearly 50 feet by 60 feet at its center. At several compounds, particularly where they front major streets, archaeologists in the 1920s found round stones and columns that were long interpreted as cultic objects. However, recent excavations at Dholavira, which is built largely of stone, have uncovered many objects identical to these clearly used as pillars. Vidale believes these well-crafted and costly artifacts testify to the wealth and status of some of Mohenjo-Daro’s citizens. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

“He also suggests these compounds can tell us much about the way Mohenjo-Daro was organized and governed, long a key question. “Instead of being dominated by a single lord,” says Vidale, “the city was made up of powerful clans who shared the same ideology.” Kenoyer has come to a similar conclusion about Harappa, which has evidence of similar walled compounds. He thinks these structures point to cities controlled by competing elites, possibly merchants, religious leaders, or landowners, who lived in their own well-defined neighborhoods.

“Despite its large population and prestige-seeking clans, there does not appear to be significantly more concentrated wealth or presence of exotic goods at Mohenjo-Daro than at other Indus sites. “Mohenjo-Daro,” he says, “was not the result of master urban planners who decided to lay out a majestic city.” The final result, however, was impressive. The citadel that forms the height of Mohenjo-Daro was clearly a planned effort, with enormous walls enclosing a raised platform that is 200 yards long and 400 wide.”

Mohenjodaro

Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro

The Great Bath in Mohenjo-Daro is probably the most impressive sight in the ancient city. About the size and depth of a modern swimming pool, it is 39 feet long, 23 feet wide and 8 feet long. It has steps that lead to the bottom and was comprised of brick walls sealed with bitumen. The floor even slants towards a drain. Some scholars believe it may have been the Indus’s equivalent of a temple. Around the pool are square piles of stones that were the walls of ancient dressing rooms. The bath is well made and given a central location which some scholars say suggests made it a center of ritual bathing, similar to what takes place in the Ganges today.

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “This bathing facility, called the “Great Bath,” was sealed with bitumen to retain water, and may have been at the center of the city’s ritual life. Recently archeologists have identified a second, smaller bath in what likely was a private compound. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

The steps around the pool lead to verandahs, galleries and rooms. The pool was filled with water from a well nearby. Rama Shankar Tripathi wrote in in 1942: “Its drain with a corbelled roof, more than six feet in height, deserves particular mention. Another accessory to the great Bath is probably a hammam or hot-air bath, pointing to the existence of “a hypocaustic system of heating.” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Mysteries of Mohenjo-Daro

Mohenjo-Daro has many secrets and mysteries. Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “Archaeologists still don’t know the city’s true size, who ruled there, or even its ancient name—Mohenjo-Daro (“Mound of the Dead”) is the site’s name in modern Sindhi. Despite its arresting standing remains, however, Mohenjo- Daro has largely baffled archaeologists. No rich tombs and only a handful of small statues and an occasional seal with symbols that remain undeciphered have been found. There were some large structures on the citadel, including one dubbed the “Granary” (sometimes identified as a meeting hall or public bath) and another called the “Great Bath.” [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

“But there are no obvious palaces or temples, in stark contrast to Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia, where remains of such monumental buildings are common. At Mohenjo-Daro and other Indus sites, early archaeologists did find standardized bricks, common weights, intricate beads, and evidence of urban planning, all of which point to a well-organized society with no clear signs of major and metals gathered from all points of the compass, and a sophisticated water system unmatched until the imperial Roman period two millennia later. Instead of the strongly egalitarian society imagined by some scholars, most now believe that Mohenjo-Daro had elite families who vied for prestige, building massive compounds with large paved courtyards and grand columned entrances on wide streets. Looming over all was an acropolis dotted with majestic structures, possibly including an enormous stepped temple.

“In the mid-twentieth century, Giuseppe Tucci, an archaeologist at La Sapienza at Rome, quipped, “Every day, we know less and less about the Indus.” Echoing Tucci’s sentiment several decades later, University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Gregory Possehl lamented that scholars still didn’t know what the Indus people called themselves or their cities, and that there were no king lists, chronologies, commercial accounts, or records of social organization of the type that aided scholars of other ancient civilizations.”

Determining the Size of Mohenjo-Daro

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “ Situated on a small ridge formed during the Pleistocene era, Mohenjo-Daro was located near the Indus River, covered at least 600 acres, and harbored a population of at least 40,000 in its heyday, although current work suggests that both these numbers underestimate its true size. With a possible population of 100,000, Mohenjo-Daro would have been bigger than Egypt’s Memphis, Mesopotamia’s Ur, or Elam’s Susa in today’s Iran, some of the ancient Near East’s largest metropolises. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

“In the coming year, scientists may have the first chance in decades to locate Mohenjo-Daro’s true boundaries. Michael Jansen, an architect recently retired from the University of Aachen who has devoted decades to understanding the site, says that much remains deeply buried in fine silt. Having spotted signs of urban life that don’t appear on old excavation maps, including the remains of numerous buildings and masses of pottery, more than a mile beyond the main site, Jansen predicts that eventually Mohenjo-Daro will prove to be the Bronze Age’s most extensive and most populous city.

“Faced with future flood threats, the government of Pakistan is eager to determine the city’s extent so they can decide how to protect the site. The first step will be to drill small cores to determine where the urban center ends and the ancient countryside begins. Archaeologists hope this will eventually lead to new excavations.

Evolution of Mohenjo-Daro

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “In the past,Mohenjo-Daro was seen as possibly the world’s first planned city, created as a major capital at the start of the Indus urban phase in the middle of the third millennium B.C. Jansen still supports this idea, but others are growing increasingly skeptical. “The problem is the high water table,” explains Vidale. “When you reach [about 20 feet] below the surface, the groundwater starts to creep into the trenches.” As a result, previous researchers focused only on the later levels. “This is what gave the superficial impression of a planned city built on virgin soil,” says Vidale. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

“But more recent analysis of potsherds uncovered during earlier digs includes a type predating the urban phase. And coring at points in the city reveals some three feet of cultural material below the water table that might date back to 2800 B.C. —and possibly much earlier. Vidale argues that Mohenjo-Daro is like other Indus settlements, including Harappa and Farmana, growing over time from modest, indigenous pre-urban roots, with large-scale mounds eventually forming what some call citadels.

“University of Wisconsin archaeologist Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, who has worked both here and at Harappa, agrees with Vidale.

Buddhist Stupa at Mohenjo-Daro?

Dominating Mohenjo-Daro is a massive structure long thought to be a Buddhist stupa. Some archaeologists now suspect it may, in fact, have been constructed during the Indus era, but excavations are needed to confirm this theory.

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “At its highest point sits a prominent structure that 1920s researchers identified as a Buddhist stupa. These scholars thought the stupa, which was built with bricks and ringed by what they called monks’ cells, had been constructed in the early centuries A.D. when Buddhism was at its peak in the region. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

“This assumption derived mainly from the discovery of coins dating to that era. But in 2007, Giovanni Verardi, a retired archaeologist from the University of Naples, examined the site and noted that the stupa is not aligned in typical Buddhist fashion, along the cardinal points. The plinth is high and rectangular, not square as would be expected, and there is little pottery associated with the later period. He also concluded that the materials recovered from the “monks’” rooms were made in the Indus period. Verardi now thinks there is “little doubt” that, apart from the mudbrick dome, the “stupa” is actually an Indus building. He believes that it was likely a stepped pyramid with two access ramps, and that terracotta seals found nearby depicting what appears to be a goddess standing on a tree while a man sacrifices an animal suggest that the building was used for religious activities.

“Jansen and other archaeologists agree that Verardi’s interpretation may be correct, though they add that excavations are necessary to prove that his theory about an Indus-era temple is accurate. If it is, says Jansen, “this will turn our interpretations upside down.” No temples have been discovered at any Indus site, an absence unique among major ancient civilizations. But the presence of a stepped platform in the heart of its largest city would link the Indus with a tradition of religious buildings that by 2000 B.C. had spread across the Middle East and Central Asia.”

Archaeology at Mohenjo-Daro

Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro began in 1921 and have continued sporadically for almost a century. Beginning at the exposed top layer, archaeologists dug down more than 40 feet in some areas to uncover at least seven occupation layers spanning more than 700 years. Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “A decades-long excavation ban, frequent political upheaval, and futile past conservation efforts have made it challenging for archaeologists to understand the site. To many, Mohenjo-Daro remains a dull, monochrome city, lacking the monuments, temples, sculptures, paintings, and palaces typical of contemporary Egypt and Mesopotamia in the third millennium B.C. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

Now, however, archaeologists are using old excavation reports, remote sensing data, and computer modeling techniques to reexamine the reputation of what was the largest city of the Indus River civilization and perhaps the entire Bronze Age. Once dismissed as a settlement dominated by similar-sized, cookie-cutter dwellings, Mohenjo-Daro is being recast as a vibrant metropolis filled with impressive public and private buildings, artisans working with precious stones and realized they had stumbled on a civilization rivaling ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was largely forgotten.

“At Mohenjo-Daro questions still outweigh answers. Dating based on old excavations remains imprecise. There are no plant or animal remains that would help answer questions about diet, the economy, and the city’s relationship to its hinterland. There also is no excavated cemetery to tell us about the health of its citizens and their social standing, or whether people immigrated to the city from far-flung locations. But Jansen has assembled a vast archive of photographs and dig reports, and says that there is an “enormous amount” of data waiting to be interpreted. Only 10 percent of the known site has been dug, and no major excavations are in the offing. But Fazal Dad Kakkar, director general of Pakistan’s museums and ancient sites, says he hopes to begin coring around the perimeter soon. These cores could provide welcome new materials for radiocarbon dating as well as botanical and zoological evidence, and knowing the city’s true extent is critical for conservation and preservation. Despite the hurdles, Jansen is optimistic about Mohenjo-Daro’s future. “The city may be twice as big as we thought,” he says. “Our task now is to find its limits.”

Archaeology Challenges at Mohenjo-Daro’s

Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro were halted in the 1960s when excavated bricks began to crumble after being exposed to air. The problem was s that the bricks had been soaked in ground water, leaving behind salt. Exposure to the sun and air drew out the moisture, leaving behind the salt, causing the bricks to crumble. Early excavators used picks and worked without sieves. Probably thousands of small finds that might have revealed architectural details have been lost.

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “Work at the site continued sporadically during the 1940s and 1950s, but the last major digs were in the mid-1960s, after which the government of Pakistan and UNESCO forbade new excavations since the opened areas were quickly deteriorating. Salt had leached from the ancient bricks, causing them to begin to crumble away. Although millions of dollars were spent over the next two decades on expensive pumps in an attempt to lower the groundwater level, that effort proved futile. It was discovered that the real culprit was the damp winter air. The fragile ancient bricks have since been treated with mud slurry, but the results have been mixed and the site’s condition remains a major concern.

“When the Indus River swelled in 2011 in central Pakistan, the floodwaters came within just three feet of overtopping an earthen embankment ay Mohenjo-Daro. At the time, archaeologists breathed a sigh of relief. But in September 2012 monsoon rains again threatened the site, lashing at the exposed walls and sparking new fears that this 4,000-year-old metropolis may be destroyed before it yields its secrets.”

Conservation at Mohenjo-Daro

According to UNESCO: “The Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro comprise burnt brick structures covering 240 hectares, of which only about one third has been excavated since 1922. All attributes of the property are within the boundaries established for proper preservation and protection. All significant attributes are still present and properly maintained. However the foundations of the property are threatened by saline action due to a rise of the water table of the Indus River. This was the subject of a UNESCO international campaign in the 1970s, which partially mitigated the attack on the mud brick buildings. [Source: UNESCO]

“The Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro are being protected by National and Regional laws including the Antiquities Act 1975 from the threats of damage, pillage and pilferage and of new developments in and around the boundaries of the property. There is a management system to administer the property, protect and conserve the attributes that carry Outstanding Universal Value, and address the threats to and vulnerabilities of the property as outlined above. A comprehensive Master Plan has been prepared by the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan to identify the actual extent of the archaeological area of Mohenjo-Daro. However during the process of approval of the Master Plan, the archaeological area of Mohenjo-Daro has been transferred from the Federal Department of Archaeology to the Culture Department, Government of Sindh. Under the Constitution Act 2010 (18th Amendment), the Culture Department, Government of Sindh is now responsible for the proper up-keep and maintenance of the property.

“In order to tackle the potential weaknesses as mentioned in the statements of authenticity and integrity there is a site office supported by a scientific laboratory to deal with the issues of conservation and other problems in a scientific way with traditional methods. The problems of salt action, thermal stress and rain are dealt with through a holistic approach involving application of mud slurry, mud capping, re-pointing and other consolidation works such as under- pinning in order to retain the authenticity and integrity of the property. Besides the above threats there is the danger of flood which was mitigated to some extent by constructing embankments and spurs. However, a breach of the dam upstream would cause catastrophic damage. The Department is therefore undertaking regular monitoring of the dam and is seeking secure funding from the Government, NGOs and other donor countries in order to strengthen it.”

Mohenjo-Daro Archeological Museum

Mohenjo-Daro Archeological Museum has a collection of fascinating artifacts excavated from the sight. Among the items are gold jewelry, an ancient balance with weights, steatite seals and bead necklaces. There is also a clay figurine of a Mother Goddess, a terra cotta lion head statue and a terra cotta toy cart pulled by terra cotta water buffalos. The most interesting objects are old dice, which have the dots configured exactly as they are today and an old game board that looks like something the Flintstones played on. Similar dice have been found in ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman sites.

The Mohenjo-Daro Museum is close to the archaeological site. It houses finds from the excavations. These include, amongst other things, engraved seals, ornaments, utensils, pottery weapons, figurines, toys, jewelry, tools, and the famous seals depicting animals and the still undeciphered Indus Valley Civilization script. ..

Miniatures of decorated women with headdress collected from Mohenjo-Daro seem to suggest the civilization worshipped mother-goddess figures. Some also believe they paid homage to phallic gods as well as a kind of balance. Seals contain images of figures with a human face, the trunk of elephant, the hind quarters of a tiger and the hind legs of bull, which some scholars say suggest the ancient Indus people worshiped animal cults. Found on a three sided seal was a squatting god surrounded by animals which may represent a forerunner of the Hindu god Shiva. .

Hours: April to September: 8.30am – 12.30pm and 2.30pm to 5:00pm; October to March: 9:00am to 4:00 pm/

Visiting Mohenjo-Daro

Visitors wishing to stay overnight can put up at the archaeological department’s rest house or the newly built PTDC Motel, which also has a restaurant. Room charges are very reasonable. Nearby Sukkur and Mohenjo-Daro, can be reached by air, rail and road from Karachi..

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2020