VEDIC PERIOD (1500–500 B.C.)

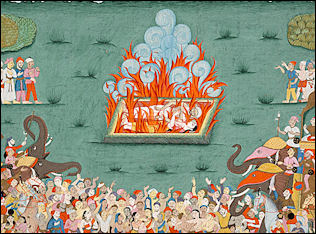

Hindu fire ritual The Vedic Period, (1500–500 B.C.) was characterized by instability as petty states, emerging larger kingdoms and a series of invading groups contending for power. During this period, Indian village and family patterns, along with Brahmanism—one form of Hinduism—and its caste system, became established. Among the classic pieces of literature that arrived at this time were the two Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Professor Gavin Flood of Oxford University wrote: “There are two sources of knowledge about this ancient period - language and archaeology - and we can make two comments about them. Firstly, the language of vedic culture was vedic Sanskrit, which is related to other languages in the Indo-European language group. This suggests that Indo-European speakers had a common linguistic origin known by scholars as Proto-Indo-European. Secondly, there does seem to be archaeological continuity in the subcontinent from the Neolithic period. The history of this period is therefore complex. One of the key problems is that no horse remains have been found in the Indus Valley but in the Veda the horse sacrifice is central. The debate is ongoing. [Source:Professor Gavin Flood, BBC, August 24, 2009 |::|]

There have been two major theories about the early development of early south Asian traditions: 1)The Aryan migration thesis: that the Indus Valley groups calling themselves 'Aryans' (noble ones) migrated into the sub-continent and became the dominant cultural force; and 2)The cultural transformation thesis: that Aryan culture is a development of the Indus Valley culture. According to the The Aryan migration thesis there were no Aryan migrations (or invasion) and the Indus valley culture was an Aryan or Vedic culture. According to the cultural transformation thesis Hinduism derives from their religion recorded in the Veda along with elements of the indigenous traditions they encountered. |::|

By the late Vedic period There is ample evidence to show that large cities had now sprung into existence, and the people enjoyed a more settled form of life. We learn, for instance, of Kampilya and Asandivant, the capitals of the Pancalas and Kurus respectively. References are also made to Kausambi and Kasi; the latter is still a great living town. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Rigveda and the Later Vedas

The Aryans did not have a script, but they developed a rich tradition. They composed the hymns of the four vedas, the great philosophic poems that are at the heart of Hindu thought. Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore said: "The hymns are a poetic testament of a people's collective reaction to the wonder and awe of existence....A people of vigorous and unsophisticated imagination awakened at the very dawn of civilisation to a sense of inexhaustible mystery that is implicit in life." [Source: Glorious India ]

The "Rigveda" is the first composition of the time. The "Rigveda" consists of verses composed in praise of the different forces in Mother Nature looked upon as deities. The other three vedas are "Yajurveda", "Samaveda" and "Atharvaveda". The " Yajurveda" provides information about sacrifices in prose. The "Samaveda" provides guidance on the singing of Rigvedic verses with the set rhythms and tunes. The Samaveda is believed to be the foundation of Indian Cultural Songs and Music. The "Atharvaveda" consists of philosophy and lists solution to day-to-day problems, anxieties and difficulties. It also includes information on Medicines and Herbs.

The Rigveda is a collection of 1017 hymns, supplemented by others called Valakhilyas, It is systematically arranged into 10 mandalas or books. The hymns represent compositions of different periods, and are of varying degrees of literary merit, being productions of priest-poets — mostly men and two or three women — of various families. Excepting a few hymns, they are all invocations to the gods, conceived as personifications of the powers of Nature, to bestow spiritual and material favours on the worshippers. It is only those that are not directly addressed to the deities, which incidentally throw some light on princely liberality and tribal wars, as well as on the life and habits of the people. The information, scanty no doubt, is all the more valuable in the absence of any other material remains for giving us a glimpse into this distant age. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Brahmanas: After the Vedas, the second-most important literature of Aryans is the Brahmanas. They were composed to illustrate the use of Vedas in sacrificial rituals. Each Veda has independent Brahmanas.

Upanishads: The term "Upanishad" indicates knowledge acquired by sitting close to the teacher. This consists of discussions on several problems such as creation of the universe, the nature of God, the origin of mankind, etc.

The period of the composition of "Rigveda" and the subsequent literature upto the "Upanishads" is approximately 1000 years. This period is divided into two parts - The Vedic (from 1500 B.C. to 1000 B.C.) and the Later Vedic (from 1000 B.C. to 600 B.C.).

Vedas as Historical Guides on the Aryans

Sati, Hindu widow burning Through the Vedas we gain knowledge of their social life and philosophy of the Vedic period. Information about the early Vedic period is gleaned from the Rigveda. In the later Vedic Period we have to depend upon the Yajurveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda, the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas, and the Upanisads, all religious works, for the later Vedic period, which, roughly speaking, comes down to about 600 B.C.

Little is known about Indian society during the Vedic period because of inadequate archaeological evidence. It is believed that India was now inhabited by peoples of two distinct cultures: an indigenous group (often called Dravidians), and the Aryans who were of the same stock as the nomads who inhabited the heart of the Eurasian continent. The Aryans were wandering herdsmen without the settled lifestyle, permanent architecture, and systematic urban planning observed in the Indus civilization. They invaded India, imposing their social and philosophical ideas and introducing a pattern of life that was to persist for centuries. During this time period two groups of religious scriptures came into existence - the Vedas and the Upanishads - which had a profound effect on the development of Indian culture, thought, and religion. [Source: Glorious India ]

Although archaeology has not yielded proof of the identity of the Aryans, the evolution and spread of their culture across the Indo-Gangetic Plain is generally undisputed. Modern knowledge of the early stages of this process rests on a body of sacred texts: the four Vedas (collections of hymns, prayers, and liturgy), the Brahmanas and the Upanishads (commentaries on Vedic rituals and philosophical treatises), and the Puranas (traditional mythic-historical works). The sanctity accorded to these texts and the manner of their preservation over several millennia — by an unbroken oral tradition — make them part of the living Hindu tradition. [Source: Library of Congress *]

These sacred texts offer guidance in piecing together Aryan beliefs and activities. The Aryans were a pantheistic people, following their tribal chieftain or raja, engaging in wars with each other or with other alien ethnic groups, and slowly becoming settled agriculturalists with consolidated territories and differentiated occupations. Their skills in using horse-drawn chariots and their knowledge of astronomy and mathematics gave them a military and technological advantage that led others to accept their social customs and religious beliefs (see Science and Technology). By around 1,000 B.C., Aryan culture had spread over most of India north of the Vindhya Range and in the process assimilated much from other cultures that preceded it (see The Roots of Indian Religion). *

Dating the Vedas and the Area Described by Them

There is a some debate surrounding the exact history and date of the Vedas. One source above says they were composed between 1500 B.C. and 600 B.C. Another says they got their present form between 1200-200 B.C. Many say they dates back to 1900 B.C., or even 4000 B.C. They were first translated into European languages in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At this time, it was widely believed to their makers could not have made something older than classic European texts. That idea persisted for some time the West. Today, some India historians are trying push the origin of The Vedas back to the beginning of dawn of human civilization between 4000 and 3000 B.C.

Dr. Michael Witzel, Wales Professor of Sanskrit, Harvard University, said the Rig Veda is no older than 1400 B.C., based on the references to metals (bronze, and no iron), horses, and chariots. He maintains that there was no evidence to support earlier dates. He also said that Vedic Sanskrit was imported to the region, as shown by the similarity with many other languages, although there was a local substratum of language and customs that were retained in the Vedic times. [Source: Science Center at Harvard University, On 14 March 2010, lokvani.com]

During this age the Aryan civilisation gradually extended towards the east and the south. The north-western parts of India, the home of the Rigvedic tribes, fade into unimportance, and even the customs of those still dwelling there are viewed with disfavour. The centre of culture shifts to Kuruksetra; and Madhyadesa, the land of the Yamuna and the Gariga, comes into prominence. KoSala (Oudh), KasI, and Videha (North Bihar), rise as great Aryan centres in the east. Mention is also made of Magadha (South Bihar) and Anga (South-eastern Bihar), although these regions had not yet been Aryanised and their inhabitants were regarded as strangers. We now hear for the first time of the Andhras and other out-cast tribes like the Pundras of Bengal, the Sabaras of Orissa and C.P., and the Pulindas of South-western India. Vidarbha or Berar occurs in two late passages of the Aitareya and Jaimimya Brahmanas. Thus, nearly the whole of Northern India from the Himalayas to the Vindhyas, and perhaps even beyond, had now come within the ken of the Aryans.

Comparing Indus Valley and Rigvedic Aryan Cultures

The Aryans were initially nomadic. They tended sheep, goats, cows, and horses; measured their wealth in herds of cattle and depended on their cows and other livestock for food. Cows were a sign of wealth . Over time, the Aryans settled into villages. Each village or group of villages was led by a headman and council. The Aryans are believed to have brought with them the horse, developed the Sanskrit language and made significant inroads in to the religion of the times. All three factors were to play a fundamental role in the shaping of Indian culture. Cavalry warfare facilitated the rapid spread of Aryan culture across North India, and allowed the emergence of large empires. Sanskrit is the basis and the unifying factor of the vast majority of Indian languages. [Source: Glorious India ]

Indus Valley Civilization It may be interesting to note the dissimilarities between the Indus and Rigvedic cultures. The IndoAryans were still in the village state, living in small thatched houses of bamboo. The Indus people, on the other hand, had developed a complex city life with commodious houses of brick, equipped with bathrooms, wells, and sanitation. The metals known to the Rigvedic Aryans were gold, copper or bronze, and perhaps iron. The Indus people have left no trace of iron; they used silver more commonly than gold, and their utensils and vessels were made of stone — a relic of the Neolithic age — as well as of copper and bronze.

The weapons of offence were almost the same in both the ages, but the defensive helmet and coat of mail, known to the Rigvedic people, were not a feature of the Indus civilisation. It appears from the numerous seals discovered at Mohenjo-daro that the bull was their most important animal, but during the Rigvedic period the cow takes its place. The horse was unfamiliar to the Indus valley people, whereas the Rigvedic Aryans had domesticated it. Further, in the Indus valley the worship of the phallic symbols was current; the Rigveda, however, shows no trace of it.

The Indus people knew some sort of writing, and in art they had made considerable progress. The Rigvedic age is, however, devoid of any tangible proofs of Aryan achievement in this direction. These points of difference are enough to show how wide is the gulf between the two civilisations. And it was not a hiatus in time only, for either hypothesis, that the one was the progenitor or the descendant of the other, would land us in a difficulty or dilemma. The only possible assumption, which may satisfactorily explain the divergent characters of the Indus and Rigvedic cultures, is that the latter, although later, was unrelated to the former and had an independent origin and development.

Vedic Period Religion

Professor Gavin Flood wrote: “If we take 'Vedic Period' to refer to the period when the Vedas were composed, we can say that early vedic religion centred around the sacrifice and sharing the sacrificial meal with each other and with the many gods (devas). The term 'sacrifice' (homa, yajna) is not confined to offering animals but refers more widely to any offering into the sacred fire (such as milk and clarified butter). |::|

“Some of the vedic rituals were very elaborate and continue to the present day. Sacrifice was offered to different vedic gods (devas) who lived in different realms of a hierarchical universe divided into three broad realms: earth, atmosphere and sky. Earth contains the plant god Soma, the fire god Agni, and the god of priestly power, Brhaspati. The Atmosphere contains the warrior Indra, the wind Vayu, the storm gods or Maruts and the terrible Rudra. The Sky contains the sky god Dyaus (from the same root as Zeus), the Lord of cosmic law (or rta) Varuna, his friend the god of night Mitra, the nourisher Pushan, and the pervader Vishnu.” |::]

The religion of the Rigveda is essentially simple, though it has many gods. This is natural, as the hymns are the product of a long period of priestly effort, and represent the deities of the various tribes. Most of the objects of devotion are the personifications of natural phenomena. They may be broadly classed as 1) Terrestrial gods, like Prithvi, Soma, Agni; 2) Atmospheric gods, like Indra, Vayu, Maruts, Parjanya; 3) Heavenly gods, like Varuna, Dyaus, ASvins, Surya, Savitri, Mitra, Pushan, and Visnu — the latter five forms being all associated with the different phases of the sun’s glory. Among these deities, Varuna occupies the place of honour, and is extolled in many a sublime hymn. He is god of the sky, and with him is bound up the conception of rita, first indicative of the cosmic and then of moral order. Next comes Indra, the god of thunder-storm, whose majesty is another favourite subject of praise. He causes the rain to fall and thus relieves the dryness of the earth. His importance grew with the advance of the Aryans to regions noted for storm and seasonal rainfall. It must not, however, be supposed that any kind of hierarchy among the gods was in the course of formation. The Rigveda also refers to some minor deities like the Ribhus (aerial elfs) and Apsaras (water-nymphs). [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

See Separate Article ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY OF HINDUISM factsanddetails.com

Aryans and Hinduism

Indus swastika seal

The Hindu religion is thought to have originated with the Aryans. The Aryans were originally nature worshipers who revered a number of gods and believed that their gods represented forces of nature. Most of the important deities were male, including a celestial father and a king of gods who lit up the sun, exhaled the wind and knew the pathway of the birds. There is some evidence of tree worship. Some early Aryan structures appear to have been built around trees.

Brahmins, a priestly class sort of like the Druids, were the only people who could perform religious ceremonies based initially on knowledge that was passed down orally over the centuries. Their ability to memorize was quite extraordinary because the rituals they presided over were quite involved and complex. The hymns and knowledge associated with these rituals has survived intact since 1000 B.C.

Aryans that settled in the Punjab and wrote hymns to natural deities of which 1028 were recorded in the Verdic verses. The “Brahmanas” were written between 800 and 600 B.C. to explain the hymns and speculate about their meaning.

Among the differences between the early Aryan religion and Hinduism are: 1) Aryan religion had no icons and no personal relationships with a single supreme deity whereas Hinduism does; 2) Aryan offering were made for something in return while Hindus make offering as a sign of worship; 3) The Aryan gods rode chariots while Hindu ones ride mounted on their animals; and 4) nearly all the early Aryan gods were male while Hindus have male and female gods as well as ones with cobra heads and ones that are worshiped with phallic symbols. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Tribal Divisions and Wars During the Early Vedic Period

The Rigvedic Aryans were not a homogeneous lot. They were divided into several tribes, the most important having been the five allied ones, viz.. Anus, Druhyus, Yadus, Turvasas, and Purus, who dwelt on either side the Saraswati. Besides these, mention is also made of the Bharatas (later merged into the Kurus), Tritsus, Srinjayas, Krivis, and other minor tribes. Quite often, they were fighting among themselves, and one of the notable events of Rigvedic history was the great Battle of the Ten Kings near Parusni River in which Sudas, king of the Bharatas, defeated with heavy losses the confederate tribes led by ten kings under the guidance of Svatoitra. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The victory is celebrated by his family priest, VaSistha, but we do not know if Sudas attempted any consolidation of his conquests. Close upon the heels of the attack by the above-mentioned five allied tribes and by those of the North-west, Alinas, Pakthas (cf. modern Pakhthun or Pathans), Sivas, Bhalanases, and the Visanins, he had to face another crisis on the eastern side of his kingdom. Sudas, however, overcame it by successfully repulsing his assailants under the leadership of Bheda near the Jumna. The latter was perhaps a non-Aryan chief, as the curious names of the three tribes — Ajas, Sigrus, and Yaksus — under him suggest. Thus, besides inter-tribal warfare, the Aryans were engaged in struggles with the “Dasyus” or “Dasas”. They were carried on with unceasing relentlessness, for the two peoples had strong differences, both racial and cultural. The Aryans were tall and fair, and the “Dasyus” were dark-skinned and of short stature. They did not believe in Vedic gods indeed reviled them never performed sacrifices or any rites but worshipped the phallus emblems and followed strange laws. Their speech was unintelligible

These characteristics indicate that the “Dasyus” probably belonged to the Dravidian stock, then occupying the parts over which the Aryans were seeking to establish their domination. The “Dasyus” fought valiantly in defence of their homes and herds of cattle, and they yielded to the superior might of the Aryans only when the destruction of their puras and durgas, towns and crude fortifications, made further resistance futile. Many of the ‘Dasas’ became slaves (dasa= slave) of the conquerors, having been admitted in society as Sudras, but others retired into the jungles and mountain fastnesses, where we still find their descendants living in primitive conditions.

Government and Political Organization During the Vedic Period

Prior to the Mauryan Empire (321 to 185 B.C.) there was no organized Aryan government with a class of bureaucrats that acted as administrators. Instead there were numerous ruling chieftains (“rajan” ), who were like warlords. They ruled with the support of armies and militias. They were counseled by “purohitas” , shaman-like figures believed to possess magical powers. When large kingdoms emerged the purohitas served as the equivalent of archbishops and prime ministers for the rulers, performing ritual sacrifices and giving political counsel. Commoners showed respect by kissing the feet of their sovereigns.

Custom was law, and kings and chief priests were the arbiters, perhaps advised by certain elders of the community. An Aryan raja, or king, was primarily a military leader, who took a share from the booty after successful cattle raids or battles. Although the rajas had managed to assert their authority, they scrupulously avoided conflicts with priests as a group, whose knowledge and austere religious life surpassed others in the community, and the rajas compromised their own interests with those of the priests. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Magistrates in ancient India used 18 different kinds of torture including beating the soles of the feet, hanging people upside down, and burning the finger joints. For severe crimes all 18 punishments were meted out in a single day. For lesser offenses they were dished out one a day for 18 days. Prisoners of war in ancient times were not used as slaves but deported to a different part of the kingdom. Suspected criminals were forced to chew and spit out rice grains. Grains stuck in the teeth were seen as signs of guilt.

The family (griha or kula) was the ultimate basis of the Vedic state. A number of families, connected with ties of kinship, formed the grama. An aggregate of villages made up the vii (district or clan), and a group of vii composed the jana (tribe). The tribe was under the rule of its chief or king (rajan), who was often hereditary, as would appear from several lines of succession mentioned in the Rigveda 1. Occasionally the Rajan was elected by the vis, but it is not clear whether the choice was limited to members of the ruling house or was extended to other noble families. The king led the tribe in battle, and ensured their protection, in return for which the people rendered him obedience or gave voluntary gifts. Perhaps the king did not then raise any fixed taxes for the maintenance of the royal state. When free from fighting, he dispensed justice and performed sacrifices for material prosperity. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The Purohita, besides the Senani (‘leader of the army’) and the Gramani, was the most important member of the royal entourage. He received gifts and by spells and incantations prayed for his master’s success in all undertakings. The king was by no means an autocrat; his powers were limited by the will of the people as expressed in the Sabba (‘council of Elders’) and Samiti (‘assembly of the whole people’). The states were usually small, but due to wars and the “Dasyu” menace the tendency to coalesce under an overlord, or evolve bigger territorial units, had already started.

Tribal Groupings and the Rise of Kings and Powerful States in the Late Vedic Period

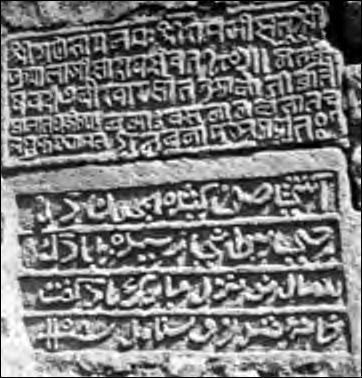

ancient Sanskrit inscriptions In addition to the above changes, we find a noteworthy change in the relative importance of the different tribes. The Bharatas of the Rigveda are no longer a mighty political unit; their place is taken by the Kurus and their neighbours and allies, the Pancalas. It appears that the Bharatas and Purus were merged into the Kurus. The Pancalas were also a composite clan, as their name, derived from pane a — five, shows. According to the Satapatha Brahmana, they were formerly called Krivis, who may, therefore, have been one of the constituent tribes. Perhaps the earlier Anus, Druhyus, and Turvasas, that disappear now from history, were also comprised in the confederation. The Kurus and Pancalas are held out in the texts as examples of good manners and pure speech. Their kings are model rulers, and their Hindus are celebrated for learning. They (Kuru-Pancalas) undertake military operations in the right season, and their sacrifices are performed with the minutest details and care. Their close neighbours in the Madhyadesa were the Salvas on the Jumna, the VaSas and the USinaras, who did not play any conspicuous part. The Srinjayas were another tribe, who seem to have been allied with the Kurus, as they had at one time a common priest. We also hear of the Matsyas, who were settled round about modern Jaipur and Alwar. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The amalgamation of tribes and their wars of aggrandisement gradually led to the formation of bigger territorial units as compared with those of the Rigvedic times. The ideal of ‘paramountcy’ or “universal sovereignty” now began to loom large on the political horizon, and kings performed sacrifices like the ‘Vajapeya’, the ‘Rajasuya’ and the ASvamedha’ to symbolise the degree of success achieved in realising their ambitions. The Aitareja and Satapatha Brdhmanas mention the names of some monarchs, who performed the ASvamedha’ sacrifice along with the Aindra Mahabhiseka,’ such as Para of KoSala, Satanlka Satrajita, and Purukutsa Aiksvaka, etc. As the kings extended their sway, their titles also changed. Thus, Raja was used for an ordinary ruler, and Adhiraja, Rdjadhiraja, Saturate Virdt, Ekarat, and Sarvabhauma denoted various gradations of suzerains. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

With the emergence of larger realms, the importance of the royal rank also grew. This is reflected in the importance attached to, and elaboration of, the consecration ceremony itself, in which figured prominently such state functionaries as the Turohita, the Rdjanja (noble), the Mahisi (chief queen), the Sut a (charioteer or bard ?), the Senani (army commander), the Grdmani (village headman), the Thdgadugha (collector of taxes), Ksattri (Chamberlain), Samgrahitri (treasurer), Aksavdpa (superintendent of dicing), and others.

The king, whose position was commonly hereditary, still led in war, although minor operations were entrusted to the Senani. He (i.e., the king) punished the wicked, and upheld the Law, Dharrna. He controlled, if not owned, the land, and he could deprive any individual of it. Misuse of the latter prerogative must have meant considerable hardship to the commoner. Popular assemblies like the Sabha and the Sam it ip not quite defunct yet, are rather rarely heard of during this period. The growth in the size of the kingdom must have made their frequent meetings difficult, and in consequence their control or check over the ruler must have progressively decreased. The will of the people, however, sometimes asserted itself. Thus a king named Dustaritu was expelled by his discontented subjects, but he was subsequently restored to the throne by his Sthapati Cakra. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Family Life in the Vedic Period

The basic unit of Aryan society was the extended and patriarchal family. A cluster of related families constituted a village, while several villages formed a tribal unit. Child marriage, as practiced in later eras, was uncommon, but the partners' involvement in the selection of a mate and dowry and bride-price were customary. The birth of a son was welcome because he could later tend the herds, bring honor in battle, offer sacrifices to the gods, and inherit property and pass on the family name. Monogamy was widely accepted although polygamy was not unknown, and even polyandry is mentioned in later writings. Ritual suicide of widows was expected at a husband's death, and this might have been the beginning of the practice known as sati in later centuries, when the widow actually burnt herself on her husband's funeral pyre. [Source: Library of Congress]

The Rigvedic Aryans had developed a healthy family life, in which the ties of wedlock were held sacred and indissoluble. Monogamy was the usual rule, though among the “upper ten” polygamy was not unknown. There are no traces of polyandry and child-marriage. Women 1 enjoyed a certain amount of freedom in choosing their husbands, under whose protection and care they lived after marriage. Their position was of greater honour and authority at that time than is perhaps the case now. They controlled the household affairs, and participated in the sacrifices and other domestic ceremonies and feasts, gaily wearing their bright apparel and ornaments. There was perhaps no segregation of females or restriction upon their movements. They were educated, some of them like Apala, Visvavara, and Ghosa even composing mantras after the fashion of the Risis. The standard of morality was comparatively high, but occasionally we learn of cases of lapse.

Besides husband and wife, the family consisted of other members — parents, brothers, sisters, sons, and daughters, etc. Generally their relations were marked by cordiality and a spirit of mutual accommodation and help. Sometimes, however, disputes about property, specially relating to land, cattle, ornaments, etc., must have caused ill-feeling and even the breakup of the family.

Similarly, the position of women was not high in all respects. Instances of Gargi Vacaknavl and Maitreyl, of course, prove that education was imparted to females, and some of them attained to rare intellectual heights. Women could not, however, inherit or own property; and their earnings, if any, accrued to their fathers or husbands. The birth of a daughter was considered “a source of misery.” Kings and the richer people practised polygamy, which must have caused considerable irritation in the family circle.

Everyday Life in Vedic Period India

Clothes: It appears from the casual allusions to dress in the Rigveda that the people wore a lower garment (nM), another garment, and a cloak. Sheep’s wool was used for weaving cloth. They were embroidered with gold and dyed in the case of the rich, who further adorned their person's with such ornaments as ear-rings, necklets, armlets, bracelets, garlands, etc. The hair was oiled and combed. Women wore it “plaited”; and some men, too, preferred coils on their heads. Shaving was known, but beards were the norm. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Food: The Rigvedic Aryans took both animal and vegetable food. The meat of sheep and goat was freely eaten and offered to the gods. It was also customary to kill the fatted calf on festive occasions or to entertain guests, but the cow was “aghnya” — not to be slaughtered, because of her usefulness. Milk was, however, the chief article of diet. Among its various preparations, ghee and dahi (curd) were most commonly used. Grain was powdered into flour and with milk and ghee made into cakes. Vegetables and fruits were also included in the menu of the Rigvedic Indian.

Drink: Mere water and milk did not satisfy the tastes of the age. People were almost addicted to fermented drinks. On religious occasions Soma was the favourite beverage, but Surd, a spirit distilled from grain, was the ordinary drink. The priests, however, disliked its use owing to its intoxicating \character. Sometimes it led to the commission of crimes, which were by no means rare then.

Amusements: The Rigvedic Indian did not lead a dull and drab life. He was fond of merry-making and pastimes. Joyous occasions were marked by music and dancing, the latter often not quite innocent. The musical instruments included the drum (dundubhi), -the cymbal, the lute (karkari), and the flute. Singing may also have been practised for aught we know of its later development in Saman songs. Besides chariot-racing and horse-racing, gambling with dice was the most popular amusement. Despite the loss of fortune and consequent ruin, the gambling-hall was the most frequented place and offered irresistible attractions to the players.

Soma was a juice that had exhilarating effects. All efforts to identify the plant have so far not met with success. Both sexes indulged in this form of amusement. The ancient Indians also had recipes for toxic smoke that could be used in warfare.

Cannibalism in Ancient India: The were reports of cannibalism in ancient China, India and Egypt associated with exotic dishes enjoyed by the aristocracy and people surviving during famines. Early Brahminic scriptures describe how humans were sacrificed in the name of the death goddess Kali: "having placed the victim before the goddess, the worshiper should adore her offering flowers, sandal paste, and bark, frequently repeating the “mantra” appropriate for sacrifice. Then, facing the north and placing the victim to face east, he should look backward and repeat this “mantra”: "...I shall slaughter thee today, and slaughter as a sacrifice is nor murder"....The sword, having thus been consecrated, should be taken up while repeating the mantra: "Am hum phat," and the excellent victim slaughtered with it."

In the late Vedic period dress, amusements, and food remained almost the same as in the time of the R igveda. In a hymn of the Atharvaveda, however, meat-eating and drinking of Sura ace regarded as sinful acts. This may have been due to the doctrine of Ahimsa, which now begins to germinate. The later Vedic period was also probably marked by the knowledge of writing.

Aryan Culture

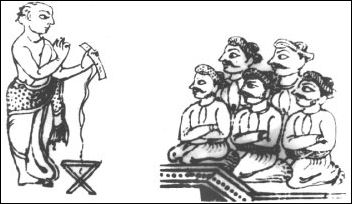

Brahmin ikshitarThe Aryans brought with them a new language, a new pantheon of anthropomorphic gods, a patrilineal and patriarchal family system, and a new social order, built on the religious and philosophical rationales of varnashramadharma . Although precise translation into English is difficult, the concept varnashramadharma , the bedrock of Indian traditional social organization, is built on three fundamental notions: varna (originally, "color," but later taken to mean social class), ashrama (stages of life such as youth, family life, detachment from the material world, and renunciation), and dharma (duty, righteousness, or sacred cosmic law). The underlying belief is that present happiness and future salvation are contingent upon one's ethical or moral conduct; therefore, both society and individuals are expected to pursue a diverse but righteous path deemed appropriate for everyone based on one's birth, age, and station in life (see Caste and Class). The original three-tiered society — Brahman (priest), Kshatriya (warrior), and Vaishya (commoner) — eventually expanded into four in order to absorb the subjugated people — Shudra (servant) — or even five, when the outcaste peoples are considered (see Varna , Caste, and Other Divisions). [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Aryans loved music, dance and poetry, They gave South Asia the Rig Vega and three other books of hymn as well as epic poems like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Their work were passed down orally rather than written down. This is especially remarkable when one considers that the Mahabharata was the largest single poem ever written.

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “No art or architecture from this period survives, perhaps because it was made with ephemeral materials such as wood and sun-dried brick. However, important philosophical and religious ideas were formulated during this time. The Aryans (meaning “the noble ones” in Sanskrit) began to migrate from Central Asia to the subcontinent about 1500 B.C. They spoke an ancient form of Sanskrit, which became the language of all the great Indic religions. Sanskrit is an Indo-European language related to ancient Greek, Latin, and the modern languages of Europe, including English. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

“With superior weapons and horse-drawn chariots, the Aryans overpowered the indigenous peoples. Their great heritage was literary: the Vedas, hymns to their gods composed before 1000 B.C., contain a rich and complex body of religious and philosophical ideas; the Upanishads (ca. 800–450 B.C.) include philosophical musings about the nature of the divine and of the human soul. Handed down orally for centuries, these beliefs were adopted as the foundation of Hinduism at the beginning of the first millennium.

Agriculture and Livestock in the Vedic Period

One of the important means of living for the Rigvedic Aryans was -cattle-breeding. Their wealth and prosperity depended upon the possession of a large number of cows, which they regarded as “the sum of all good.” We can, therefore, well understand their extreme desire to multiply them. Among other domesticated animals were houses, sheep, goats, dogs and asses. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Agriculture was their next occupation. Ploughing appears to have been an old practice of the Aryans, for it is significant the root kris occurs in the same sense in both Sanskrit and Iranian. The plough was drawn by bulls, and had a metal share to make furrows (sita) in the fields (ksetra). Water was led into them by means of channels. The corn cultivated was java (perhaps barley) and dhdnja, and when ripe, it was cut with sickles, threshed and winnowed properly, and then stored in granaries. The Rigvedic Aryans also practised hunting for sport as -well as livelihood. Birds and wild animals were caught in nets and snares (paid), or sometimes they were killed with bow and arrow. Pits were also dug for capturing deer, lion, and other beasts.

During the late Vedic period period great progress in agriculture was made. The quality and size of the plough (stra) was improved; and the use of manure was well understood for increasing production. In addition to barley (java), several other kinds of grain like rice (vrihi), wheat (godhuma), beans, and sesamum (tila) were now cultivated in their due seasons. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Economic Activity in the Vedic Period

The development of iron technology around 500 B.C. led to widespread clearing of land and changes from pastorialism to agriculture and an increase in urbanization. By this time there was also a powerful merchant class and towns were using silver and copper coins. Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, emerged from a ruling family in an Aryan kingdom around 600 B.C.

Permanent settlements and agriculture led to trade and other occupational differentiation. As lands along the Ganga (or Ganges) were cleared, the river became a trade route, the numerous settlements on its banks acting as markets. Trade was restricted initially to local areas, and barter was an essential component of trade, cattle being the unit of value in large-scale transactions, which further limited the geographical reach of the trader.

In the late Vedic period The growth of civilisation is further reflected in the knowledge of more metals. While the Rigveda mentions gold and ayas of uncertain import, this period knows of lead (sisa), tin (trapu), silver (rajata), gold (hiranya), red (lohita) ayas (copper) and dark (syama) ayas (iron). Gold and silver were mostly used for making ornaments, bowls, vessels, etc. Gold was obtained from river-beds, or from the bowels of the earth, or from ore by smelting. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Coins were unknown. Accordingly, trade was carried on by barter and the cow was regarded as the standard of value. There are grounds to believe that haggling was known, but a bargain, once made, held good. In the late Vedic period regular coinage had not yet started, though the use of Sat am ana, equivalent to ioo krisnalas or gunja berries, was leading towards it. Thus the cow as a unit of value was gradually being replaced.

Water was drawn out of wells or from rivers. Manure too, if used then, must have added to the fertility of fields. There is no mention of fishing in the Rigveda. Navigation was limited to rivers by boats of crude construction. The absence of anchor or sails indicates that the Rigvedic people did not dare go into the open sea.

Occupations During in the Vedic Period

The fertile plains of Northern India increased the material prosperity of the Aryans, and this gave rise to a variety of occupations to meet the needs of the people. We thus hear of charioteers, hunters, shepherds, fishermen, fire-rangers, ploughers, chariot-makers, jewelworkers, basket-makers, washermen, rope -makers, dyers, weavers, slaughterers, cooks, potters, smiths, professional acrobats, musicians, guards of tame elephants, and so on.

Life being still relatively simple, the requirements of the people were few, and could be easily supplied by themselves. But evidence is not lacking to show that specialisation in certain crafts had already begun. The worker in wood was an important figure in Vedic society, as his services were particularly needed in the construction of chariots, both for war and the race. He was still carpenter, joiner, and wheelright in one, and the dexterity of his art is often compared to felicity in composing hymns. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

We also learn of the worker in metal, who forged weapons, ploughshares, kettles and other domestic utensils. The general name for metal is ayas (Latin aes), which may denote either copper or bronze or iron. Goldsmiths fashioned ornaments of gold to minister to the wants of the gay and the rich. Mention is made of the tanner, who tanned leather and made such articles as bow-strings and casks. The work of sewing, plaiting of mats with grass and reeds, and weaving of cloth was mostly done by women. What is most noteworthy is that during the age of the Rigveda none of these functions bore the stamp of inferiority, as was the case subsequently, and they were carried on by the free members of the tribe.

As described elsewhere, the Aryans were then engaged in continual warfare, which was as such one of their main occupations. They fought either on foot or on chariots, drawn by horses, but horse-riding apart, cavalry is nowhere mentioned. Coats of mail (varma) and helmets of metals (sipra) were used for protection on the battle-field. The principal weapons were the bow (dhanus) and arrow (bdtia) spears, lances, axes, swords (asi), and slingstones. The warriors fought to the accompaniment of war-cries and the music of drums (dundubbi). [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

In the late Vedic period Astrologers and barbers appear as important figures. The physician healed the sick, but his profession was for some reason stamped with inferiority. Women mostly engaged themselves in dyeing, embroidery, basket-making, etc.

Aryans, Dravidians and Caste

Reciting Brahman The origin of the caste system is unknown but it may have evolved from differences between the conquering Aryans and subject Dravidians—which happened to be different in color. Aryans were relatively light skinned while Dravidians were darker. “Varna”, the Hindu word for caste, means "color."

The caste system is believed to have been introduced in its preliminary form around 1500 B.C. as a way for light-skinned Aryan invaders to keep the indigenous Dravidian people in their place. Higher castes are usually associated with whiter skin and purer Aryan descent because, it has been argued, the first light-skinned Aryan conquerors gave the conquered dark-skin Dravidians dirtier, lower status tasks. Not all scholars agree with is assessment. “Color” could be a reference to something other than skin color.

The Vedas describe Aryan society divided into the four major castes: the Brahmins (priestly caste); Kshatriyas (warrior caste), the Vaisyas (farmer caste); and Sudras (laborers). Early in Aryan history the Brahmins gained political and religious superiority over the Kshatriyas. The caste system described in the Rig-Veda may have grown out of the enslavement of people from the Indus Valley by the Aryans. The Vedas refer to conquered “Dasas” or “Dasyi” (names meaning “slaves” and probably referring to the early Dravidian-speaking Indus people).

A settled lifestyle for the Aryans brought in its wake more complex forms of government and social patterns. This period saw the evolution of the caste system, and the emergence of kingdoms and republics. The Aryans were divided into tribes which had settled in different regions of northwestern India. Tribal chiefmanship gradually became hereditary, though the chief usually operated with the help of advice from either a committee or the entire tribe. With work specialisation, the internal division of the Aryan society developed along caste lines. Their social framework was composed mainly of the following groups : the Brahmana (priests), Kshatriya (warriors), Vaishya (agriculturists) and Shudra (workers). It was, in the beginning, a division of occupations; as such it was open and flexible. Much later, caste status and the corresponding occupation came to depend on birth, and change from one caste or occupation to another became far more difficult. [Source: Glorious India ]

DNA studies of Indians have found that highest caste members have more genetic similarities with Europeans while lower caste members have more genetic similarities with Asians. This is consistent with the historical record of the Aryan invasions and links between the Aryans and members of higher castes. Some have suggested that caste may have originally been a Dravidian concept rather than an Aryan one. One argument for this is the lack of a caste system in other areas conquered by the Aryans such as Greece.

Early Caste System

Early in the Vedic period, there were distinct classes of people — the priests, the nobility and the common people — but no mention of segregation or occupational restrictions. By about 3,000 years ago, texts mention a fourth, lowest class: the Sudras. But it wasn't until about 100 B.C. that a holy text called the Manusmruti (the Laws of Manu) explicitly forbade intermarriage across castes.

The division into four classes was already referred to in a late hymn of the Rigveda but there were few clear distinctions except between the Arya and the Dasyu. By the late Vedic period divisions became more pronounced, and the caste -system was well on its way towards crystallisation. Unfortunately, the causes of this development are obscure. The starting point of these distinctions was, of course, the “colour bar” between the fair Arya and the dark Dasyu. But the constant wars of the Aryans, the growing complexities of life and political conditions, and the tendency towards specialisation in labour, gradually resulted in the formation of hereditary occupational groups. Thus, those who possessed a knowledge of the sacred lore, officiated in religious ceremonies and received gifts were called Hindus; those who fought, owned land, and wielded political power were classed as Ksatriyas; the general mass of people — the traders, the agriculturists, and the craftsmen — were grouped under the term VaiSya; and the Sudra, reserved for menial service, was generally recruited from the conquered Dasyus. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

There was, however, still no unnatural rigidity of castes as in the succeeding age. For we know that Cyavana, a Brahman seer, married Sukanya, the daughter of Ksatriya Saryata; Ksatriya rulers like Janaka of Videha, Ajatasatru of Kail, and Pravahana Jaivali of Pancala distinguished themselves in the knowledge of the Brahman; and Prince Devapi performed a sacrificial ceremony for his brother, Santanu. As local particularism and the influence of the Hindus waxed, the system began to lose elasticity, and mobility or change of occupation was disfavoured. Further, the

The Sudras are no doubt recognised as a distinct order of society in later Vedic literature, but they were regarded as impure and not fit in any way to take part in sacrifices, or recite the sacred texts. Aryan marriages or illicit relations with Sudras were severely condemned. They were also perhaps not allowed to possess property in their own right. Indeed, the Aitareya Brahmana at one place represents the Sudra as “the servant of another, to be expelled at will, and to be slain at will.” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Laws of Manu

“The Laws of Manu, dated to around 1500 A.D., represent one of the most ancient sources for our knowledge of early Indian social structure. Though it was probably written in the first or second century B.C., the traditions that it presents are much older, perhaps dating back to the period of Aryan invasions almost fifteen hundred years earlier. Manu himself was a mythical character, the first man, who was transformed into a king by the great god Brahma because of his ability to protect the people. The fact that the ancient Indians attributed the beginnings of kingship and social classes to the first man is evidence that they themselves recognized the antiquity of these institutions. [Internet Archive, from CCNY]

The Laws of Manu are also called Manava-dharma-shastra (“The Dharma Text of Manu”). Traditionally it was most authoritative of the books of the Hindu code (Dharma-shastra) in India. Manu-smriti is the popular name of the work, which is officially known as Manava-dharma-shastra.

“The Laws of Manu (excerpt) I.3. On account of his pre-eminence, on account of the superiority of his origin, on account of his observance of particular restrictive rules, and on account of his particular sanctification, the brahmin is the lord of all castes. I.4. The brahmin, the kshatriya, and the vaisya castes are the twice-born ones, but the fourth, the sudra, has one birth only. . . . I.31. But for the sake of the prosperity of the worlds, [the Creator] caused the brahmin, the kshatriya, the vaisya, and the sudra to proceed from his mouth, his arms, his thighs, and his feet.

“I.87. But in order to protect this universe He, the most resplendent one, assigned separate duties and occupations to those who sprang from his mouth, arms, thighs, and feet. X.5. In all castes those children only which are begotten in the direct order on wedded wives, equal in caste and married as virgins, are to be considered as belonging to the same caste as their fathers. X.24. By adultery committed by persons of different castes, by marriages with women who ought not to be married, and by the neglect of the duties and occupations prescribed to each, are produced sons who owe their origin to a confusion of the castes. VII.352. Men who commit adultery with the wives of others, the king shall cause to be marked by punishments which cause terror, and afterwards banish. VII.353. For by adultery is caused a mixture of the castes among men; thence follows sin, which cuts up even the roots and causes the destruction of everything. X.97. It is better to discharge one's own appointed duty incompletely than to perform completely that of another; for he who lives according to the law of another caste is instantly excluded from his own. From: A Source Book in Indian Philosophy, edited by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957).

“Duties of a Brahmin: X.75. Teaching, studying, sacrificing for himself, sacrificing for others, making gifts and receiving them are the six acts prescribed for a brahmin. X.76. But among the six acts ordained for him three are his means of subsistence, sacrificing for others, teaching, and accepting gifts from pure men. X.81. But a brahmin, unable to subsist by his peculiar occupations just mentioned, may live according to the law applicable to kshatriyas; for the latter is next to him in rank. X.82. If it be asked, "How shall it be, if he cannot maintain himself by either of these occupations?" the answer is, he may adopt a vaisya's mode of life, employing himself in agriculture and rearing cattle. X.83. But a brahmin, or a kshatriya, living by a vaisya's mode of subsistence, shall carefully avoid the pursuit of agriculture, which causes injury to many beings and depends on others. X.85. But he who, through a want of means of subsistence, gives up the strictness with respect to his duties, may sell, in order to increase his wealth, the commodities sold by vaisyas, making however the following exceptions: X.92. By selling flesh, salt, and lac [resin] a brahmin at once becomes an outcaste; by selling milk he becomes equal to a sudra in three days. X.93. But by willingly selling in this world other forbidden commodities, a brahmin assumes after seven nights the character of a vaisya. III.77. As all living creatures subsist by receiving support from air, even so the members of all orders subsist by receiving support from the householder. III.78. Because men of the three other orders are daily supported by the householder with gifts of sacred knowledge and food, therefore the order of householders is the most excellent order. III.89. And in accordance with the precepts of the Veda and of the traditional texts, the householder is declared to be superior to all of [the other three orders]; for he supports the other three.

“Duties of a Kshatriya VII.1. I will declare the duties of kings, and show how a king should conduct himself, . . . and how he can obtain highest success. VII.2. A kshatriya who has received according to the rule the sacrament prescribed by the Veda, must duly protect this whole world. VII.3. For, when these creatures, being without a king, through fear dispersed in all directions, the Lord created a king for the protection of this whole creation. VII.14. For the king's sake the Lord formerly created his own son, Punishment, the protector of all creatures, an incarnation of the law, formed of Brahman's glory. VII.18. Punishment alone governs all created beings, punishment alone protects them, punishment watches over them while they sleep; the wise declare punishment to be identical with the law. VII.19. If punishment is properly inflicted after due consideration, it makes all people happy; but inflicted without consideration, it destroys everything. VII.20. If the king did not, without tiring, inflict punishment on those worthy to be punished, the stronger would roast the weaker, like fish on a spit. VII.35. The king has been created to be the protector of the castes and orders, who, all according to their rank, discharge their several duties. VII.87. A king who, while he protects his people, is defied by foes, be they equal in strength, or stronger, or weaker, must not shrink from battle, remembering the duty of kshatriyas. VII.88. Not to turn back in battle, to protect the people, to honour the brahmins, is the best means for a king to secure happiness. VII.89. Those kings who, seeking to slay each other in battle, fight with the utmost exertion and do not turn back, go to heaven.

“Duties of a Vaisya IX.326. After a vaisya has received the sacraments and has taken a wife, he shall be always attentive to the business whereby he may subsist and to that of tending cattle. IX.327. For when the Lord of creatures created cattle, he made them over to the vaisya; to the brahmins and the the king he entrusted all created beings. IX.328. A vaisya must never conceive this wish, "I will not keep cattle"; and if a vaisya is willing to keep them, they must never be kept by men of other castes. IX.329. A vaisya must know the respective value of gems, or pearls, of coral, of metals, of cloth made of thread, of perfumes, and of condiments. IX.332. He must be acquainted with the proper wages of servants with the various languages of men, with the manner of keeping goods, and the rule of purchase and sale. IX.333. Let him exert himself to the utmost in order to increase his property in a righteous manner, and let him zealously give food to all created beings.

“Duties of a Sudra IX.334. [T]o serve brahmins who are learned in the Vedas, householders, and famous for virtue, is the highest duty of a sudra, which leads to beatitude. IX.335. A sudra who is pure, the servant of his betters, gentle in his speech, and free from pride, and always seeks a refuge with brahmins, attains a higher caste. IX.413. But a sudra . . . may [be compelled] to do servile work; for he was created by the Self-existent [Lord] to be the slave of a brahmin. IX.414. A sudra, though emancipated by his master, is not released from servitude; since that is innate in him, who can set him free from it?

Genetic Indicates the Caste System was Entrenched 2000 Years Ago

Research published in 2013 suggest the caste system in South Asia may have been firmly entrenched by about 2,000 years ago based on genetic analysis. Tia Ghose of Live Science wrote: Researchers found that people from different genetic populations in India began mixing about 4,200 years ago, but the mingling stopped around 1,900 years ago, according to the analysis published today (Aug. 8) in the American Journal of Human Genetics. Combining this new genetic information with ancient texts, the results suggest that class distinctions emerged 3,000 to 3,500 years ago, and caste divisions became strict roughly two millennia ago. [Source: Tia Ghose, Live Science, | August 8, 2013]

“Though relationships between people of different social groups was once common, there was a "transformation where most groups now practice endogamy," or marry within their group, said study co-author Priya Moorjani, a geneticist at Harvard University. Moorjani's past research revealed that all people in India trace their heritage to two genetic groups: An ancestral North Indian group originally from the Near East and the Caucasus region, and another South Indian group that was more closely related to people on the Andaman Islands. Today, everyone in India has DNA from both groups. "It's just the proportion of ancestry that you have that varies across India," Moorjani told LiveScience. To determine exactly when these ancient groups mixed, the team analyzed DNA from 371 people who were members of 73 groups throughout the subcontinent. Aside from finding when the mixing started and stopped, the researchers also found the mixing was thorough, with even the most isolated tribes showing ancestry from both groups.

“Researchers aren't sure which groups of ancient people lived in India prior to 4,200 years ago, but Moorjani suspects the two groups lived side-by-side for centuries without intermarrying. Archaeological evidence indicates that the groups began intermarrying during a time of great upheaval. The Indus Valley civilization, which spanned much of modern-day North India and Pakistan, was waning, and huge migrations were occurring across North India. Michael Witzel, a South Asian studies researcher at Harvard University, told LiveScience. Ancient texts also reveal clues about the period. The Rigveda mentions chieftains with South Indian names. "So there is some sort of mixture or intermarriage." Witzel told LiveScience.

“The study doesn't suggest that either the ancestral North or South Indian group formed the bulk of the upper or lower castes, Witzel said. Rather, when caste divisions hardened, any type of intermarriage was sharply curtailed, leading to much less mixing overall.

After the Aryans

Northern India was divided into a vast number or feudal states that probably evolved from tribal groups. The Maagadha kingdom, formed in Bihar in 542 BC, became the dominant power and was later ruled by the Maurya dynasty, founded by Chandragupta 321 BC, that united most of Northern India in a centralized bureaucratic state. [Source: World Almanac]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2015