CHINESE STOCK MARKETS

China has two major stock markets: one in Shanghai and another on Shenzhen. They opened in 1990. Their performance is measured by the Shanghai and Shenzhen Composite indexes and the benchmark Shanghai and Shenzhen 300 index. Shares are traded electronically rather than on the floor so the exchanges themselves nothing more than a bunch of guys — often bored, sometimes playing cards’sitting behind computer screens.

China has two major stock markets: one in Shanghai and another on Shenzhen. They opened in 1990. Their performance is measured by the Shanghai and Shenzhen Composite indexes and the benchmark Shanghai and Shenzhen 300 index. Shares are traded electronically rather than on the floor so the exchanges themselves nothing more than a bunch of guys — often bored, sometimes playing cards’sitting behind computer screens.

As of 2007, China had the world’s 10th largest equity market. The Shanghai and Shenzhen markets were valued at around $1.4 trillion in December 2006, compared to $20 trillion on the New York Stock Exchange.

Stock markets are not the main source of capital in China, generally banks are. Many regard the market and subject to government manipulation and affected corruption and by lack of transparency and regulations. The markets themselves have a reputation for being shady, murky, and scandal-ridden. Serious investors stayed clear of it.

In most countries, equity price are determined based on future economic condition but this is not necessarily the case in China where financial markets are restricted by the government. Because foreign investors can only buy small stacks in Chinese companies and Chinese investors generally can not buy stocks abroad, the value of stocks reflects high demand from local investors who have few other places to put their money.

ChiNext, a new Chinese stock market, modeled on the U.S.-based NASDAQ and meant to nurture small start-ups and high tech firms, began operation in Shenzhen in November 2009. The shares of all 28 companies listed on ChiNext soared on the first day it was open, some like the film studio Huayi Brothers Media Corp, by more than 200 percent. Stock sales of the listed companies, which are privately owned, were temporarily suspended because concerns about speculation and overheating. One 57-year-old woman interviewed by Yomiuri Shimbun bought 5,000 shares when the market opened and sold them 25 minutes later when they rose 70 percent for a profit of over $10,000.

Articles on CHINESE BUSINESS, TOURISM AND TRADE factsanddetails.com ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: China Stock Market News chinastockmarket.org ; Wikipedia article on the Shanghai Stock Exchange Wikipedia ; Shanghai Stock Exchange site sse.com.cn ; U.S. China Business Council uschina.org ; Asian Development Bank adb.org ; World Bank China worldbank.org ; International Monetary Fund (IMF) on China imf.org/external/country/CHN ; U.S. Commerce Department on China: commerce.gov ; China’s National Bureau of Statistics stats.gov.cn/english Huang Yasheng, who teaches at the SloanSchool of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is an expert on Chinese entrepreneurs.

Shanghai Stock Market

China’s opened it first stock exchange in Shanghai in 1990.

The Shanghai Stock Exchange is located in a 27-story glass building modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. It is a bit of facade. the floor is largely empty because trading is done electronically. The Shanghai stock market has business ties with Nasdaq. The Shanghai composite is made of all stocks traded on the Shanghai stock market. The Shenzhen stock market is much smaller.

The Shanghai market had 868 firms listed on it in October 2009. Shanghai is expected to begin listing foreign firms in 2010.

In January 2010, the Chinese government began to take measures to meets its goal of making Shanghai a global financial center by 2020. The measures include some experiments in letting investors engage in margin trading and short-selling and futures-trading that would allow investors to profit from falling market as well as rising ones. The bank HSBS is expected to be become the first foreign company to be listed on the Shanghai Market, perhaps as early as March 2010.

Chinese Companies Listed on the Stock Market

In 2005 there were 1,381 traded companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets. In 2006, 842 companies were listed in the Shanghai Stock exchange.

Ninety to 95 percent of the companies listed on the Chinese stock exchanges’such as China Telecom. Baoshan Iron & Steel and the Industrial and Commercial Bank are state-owned. Many have state-owned parent companies that are not listed and are hybrids of public and private enterprises in which the government floats minority interests to raise money while retaining the bulk of shares.

About two thirds of the shares of China’s listed companies are in state hands. Many of the stocks are over priced, in some cases selling for double the price they do in foreign markets. Private shareholders have little say in corporate decisions. Private companies can list on China's stock markets although getting such a listing can take considerable time and effort.

Some of mainland China’s largest firms prefer to list on the deeper, more stable markets in Hong Kong and overseas. China’s two Chinese oil giants, Sinopec and China National Petroleum, are sold on the Hong Kong, New York and Nasdaq stock exchanges. These days more and more large Chinese companies are listed on Chinese stock markets.

Chinese Stock Market Investors

As of 2007 about 40 to 50 percent of shares were owned by state-owned enterprises while most the remainder were owned by individual Chinese shareholders. This differs from the United States and other mature markets where institutions control 80 or more percent of shares.

Some 58 million Chinese have stock-trading accounts (2001). Playing the market is major pastime among Chinese, especially those who live in coastal areas. People from all walks of luck try their luck: housewives, retirees, yuppies, gangsters, officer workers and workers. People still sometimes wait in line for hours to sign up for brokerage firm accounts.

Many people quit their jobs, put their savings and retirement funds into trading accounts, borrow money and made trading sticks a full time pursuit. About 300,000 new share trading accounts are opened every day as more and more people become in trading known as chao gu or”stir-frying stocks.”

Several million Shanghai residents play the market at there. Traders sometimes tell stories about "Millionaire Wang," a former Red Guard who made fortune in the early days of the market, and the woman who tragically committed suicide after taking big losses only to have her stocks gain an average of three points the day after she died.

For the most part Chinese stocks can be purchased only by Chinese. Trading is dominated by the yuan-denominated shares. Chinese mutual funds are the main vehicle for individual investments. Foreign investors are barred from buying yuan-denominated shares except through the qualified foreign institutional investor program. As of December 2006, 52 firms have approval through the program to buy a total of $8.65 billion on stocks and bonds. The government has been expanding quotas to the foreign institutional investors.

IPOs and Inflated Stocks in China

Investors are particularly fond of introductory public offerings (IPO) because they are regarded as sur bets and the prices tend to be low. The 22 IPOs offered in November and December 2007 gained an average 59 percent in a matter of weeks.

China is the world’s largest market for initial public offerings (IPOs). The value of IPOs reached a world record $66 billion in 2008, up from $63 billion in 2007

The Shanghai Stock Exchnage was the second most popular place in the world for IPOs in 2007. Companies raised $48.6 billion in Shanghai as of November 2007, compared to $52 billion on the New York Stock Exchange.

The Chinese government banned IPOs for a year until May 2006. Still companies sold $24.4 billion in yuan-denominated shares in IPOs in 2006.

As a rule, Chinese stocks tend to be highly inflated. China Mobile, for example. is worth 41 percent more than AT&T (2007) but only brings in two thirds of its revenue. The Commercial bank of China is listed as being twice as valuable as the Bank of America but earns only a third of the profits of the American lender.

See PetroChina and Exxon

During the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 interest in IPOs dried up as China-focused private capital funds shifted their interest to companies with the potential to be privatized.

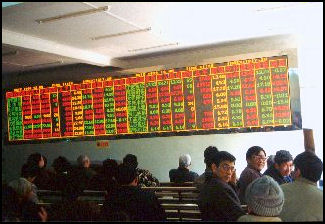

Trading Houses and Songs About Stocks in China

Many cities have private trading rooms were people gather to trade stocks and exchange tips and rumors. The rooms usually have constantly-changing electronic bulletin boards and rows of computer monitors. The atmosphere is like that of an off-track betting office. In these rooms it is not uncommon to see unemployed men pacing back and forth in their house slippers, housewives closely watching the board while playing mahjongg and knitting sweaters.

In many small trading houses traders stand before terminals and make trades using magnetic identity cards. Some trading houses have special rooms depending on how much inventors have investing with VIP rooms for the equivalent of high rollers. Investors can also trade on line, There are thousands of blogs

One of the biggest karaoke Internet hits in 2007 — I’ll Never My Sell My Shares Even After My Death — was a song about investing in the stock market written by amateur songwriter and Shanghai driver Gong Kaijie. The lyrics of the song go:

It’s not interesting unless their value has doubled

I’ll wait until their value has risen twofold

It’s really fun to make profits from stocks I bought on a whim

Other songs by Gong about the stock market include Stock Investment is Like a Song of Sadness, Investors Have No Time to Sleep and Stocks are Playing with Our Hearts. Gong told the Yomiuri Shimbun he often composes the songs while driving for a company president and that the sentiments of the songs often reflect his own investment successes and failures.

Stock Market Volatility in China

The Shanghai stock market is known for its volatility. When the market opened in 1991 Chinese stood in line for days to register for the right to buy shares. In the first half of 1992, the Shanghai index soared over 450 percent. In the second half, it plunged 72 percent, including a one-day drop of 13 percent that sent many investors into a panic.

Rises in the stock market are fueled more by speculation, profit-seeking, rumors and psychological factors than economic fundamentals Jim Rodgers, who founded the Quantum hedge fund with George Soros, told Bloomberg News, he stopped investing in Chinese stock because of “massive speculation” that had driven up prices too record highs, especially in real estate, construction and raw materials.

Rumors are spread by text messages and blogs, and Internet chat lines. Many people have lost a significant portion of their life savings investing in stocks that the government said were good investments bit turned out to have inflated export figures. Angry protest have broken out over market scandals and other malfeasance

To boost investment in the stock market: 1) bank saving account interest rates have been lowered; 2) on taxes on money from interest have been raised; 3) party newspaper have ran front page stories equating investing in the stock mare with patriotism; 4) large amount of formally state-owned shares have been put on the markets. In 2005, the Chinese government offered a plan that would allow companies to use stock options and other employee incentives and discussed compensating investors who lost money because firms went bankrupt. Many of these moves have turned off inventors rather than encouraged them.

Many investors are worried about a lack of transparency. They had hoped the stock market would do a better job diverting China’s $14. trillion in savings to companies in need of investment to grow and expand. Instead money is often spent on real estate speculation.

In June 2010, data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics was leaked, causing a surge in stocks around the world. The Chinese government did an investigation into the leak — figures on exports, consumer prices and new loans, which exceed forecasts, reported by Reuters which cited three people who heard them from a government official.

See China Aviation Oil, Transportation

Casino-Like Stock Markets in China

Chinese stock markets often behave more like casinos that equity exchanges. Trading houses have gone bankrupt and lost millions carelessly speculating with investors money. People have lost their homes and gone deep into debt mortgaging their homes and borrowing against their credit cards to buy shares. Banks have gotten stuck with bad loans from people who borrowed money to buy shares.

Some say the stock markets are worse than casinos, especially when it comes to insider trading. One Chinese economist complained to AFP, " A casino has rules...you are not allowed to look at other's cards but in our stock markets people look at other people's cards. They can cheat and they engage in stir-frying stocks." The high degree of interconnectedness between companies which creates opportunities for insider trading.

Sometimes stock investor decisions defy rational behavior. Take Worldbeat Pharmaceutical Company, for example. In 2006 and 2007 it was accused of exaggerating profits and engaging in accounting irregularities plus six people died and 80 fell ill after being given one its drugs yet its stock prices continued to rise. One investor told the Washington Post, “There’s to much speculation...If one person wants to get out, everybody wants to get out.”

China’s mutual fund industry quadrupled to $450 billion in 2007 as investors took money out of their bank accounts and invested it in the stock market. In 2007 there were 363 mutual funds companies in China.

One Shanghai investor told the New York Times, “I devoted my whole life to the country. I went to the countryside after graduation and worked as an engineer in a Shanghai factory until retirement. I invested all my savings and retirement fund in the market 10 years ago. But now I’m totally penniless. All my stocks went down.”

Suspicion of Chinese Companies by Shareholders in Overseas Stock Market

In June 2011, Reuters reported: “China is paying close attention to the slump in shares of overseas-listed Chinese companies in the wake of a string of accounting problems and is studying ways to address the issue, an official from the country's securities regulator said. Corporate misbehaviour, unfamiliarity with the U.S. market and some practices involved in overseas listings had all contributed to the recent investor distrust of Chinese companies, said Wang Ou, vice head of research at the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). [Source: Reuters, June 27, 2011]

"First, we have to admit that some of our companies may have flaws. Second, our (companies') understanding of the U.S. market and the measures to tackle risk there may be inadequate," Wang said. Wang's comments cam on the heels of a series of accounting scandals involving Chinese companies listed in North America and shareholder lawsuits alleging fraud.

Much of the questionable accounting involved reverse mergers, a type of backdoor listing in which a foreign company merges with a U.S. shell company. To overcome regulatory hurdles, many Chinese companies have also set up legal structures under which control of a mainland-based company can be transferred to an overseas entity via certain contracts.

The Economist reported: “Concerns about fraud among Chinese companies listed in North America gained more traction on June 2nd, when a short-seller named Muddy Waters accused Sino-Forest Corporation, a Toronto-listed forestry firm, of inflating its assets, among other things. The Chinese firm robustly denies the allegations; other research firms have come to its defence, although not before a precipitous fall in its shares. Similar charges have been laid in the past against Chinese firms listed in America and Singapore. The sheer number of allegations raises an obvious question: if concerns are rife in places where there is lots of scrutiny, how bad might things be in Hong Kong, the largest market for overseas Chinese listings, and on the mainland? [Source: The Economist, June 9, 2011]

The optimistic argument is that the markets that have been at the heart of the allegations have particular vulnerabilities. There is some truth to this explanation, says John Hempton of Bronte Capital, an Australian hedge fund. Lots of Chinese firms have used “reverse mergers”, in which a private company goes public by combining with a listed shell company, to float in America. That allows firms to avoid some of the scrutiny that comes with an initial public offering (IPO).

That is not to say there are no problems. The Securities and Futures Commission, the territory’s primary regulator, released a report in late March on the role played by 17 investment banks in IPOs and provided examples of sloppy due diligence, poor disclosure, failures to interview key customers (critical for confirming sales and revenues) and inadequate scrutiny of potentially illicit operations.

Allegations of fraud have been fairly rare in China.... Mr Hempton attributes this to a difference in the risks involved in cheating the markets. A Chinese manager of a dodgy company listed in America is probably beyond the reach of prosecutors; that’s not true of Shanghai-listed companies. Another reason may be less diligence: short-sellers, who often act like detectives sniffing out problems at companies, are banned in China. The most benign explanation is the gauntlet of government approvals a company needs to run to list on the two primary mainland exchanges, in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The process cripples the flow of capital to fast-growing businesses, and may feed corruption because of how important relationships are to approvals, but it may — also filter out frauds....In the meantime, doubts over how to separate bad from good hurt everyone, the blameless and the scammers. This is particularly true of ChiNext, a second Shenzhen exchange for start-ups, where companies that used to rise in unison are now all falling together.

Carson Block, Muddy Waters Research Go After Dodgy Chinese Companies

David Barboza and Azam Ahmed wrote in the New York Times, “Carson C. Block makes even Wall Street cringe.” In June 2011, “the founder of the investment firm Muddy Waters Research issued a scathing report on a Chinese forestry company, calling it a “pump and dump” scheme that has been “aggressively committing fraud.” The remarks set off a sharp sell-off in shares of the company, Sino-Forest, prompting Canadian authorities to temporarily halt trading. Since the report, the stock has fallen more than 70 percent, erasing billions of dollars in value from a company whose investors include Paulson & Company, the hedge fund run by the billionaire John A. Paulson. [Source: New York Times, David Barboza and Azam Ahmed, June 9, 2011]

“They overstated assets by billions of dollars and funneled money to an undisclosed subsidiary,” Block, told the New York Times. Sino-Forest vehemently denies his assertions and released evidence to support its position. It has said it is considering legal action against Muddy Waters, calling its report “inaccurate, spurious and defamatory.” The company has also been posting documents on its Web site to refute Mr. Block’s accusations, including bank statements and land purchase agreements.

Block got his start in his line of work after being asked by his father, William, the founder of W.A.B. Capital, to research Orient Paper as a potential investment. Block and a friend traveled to China to visit the company’s headquarters and said it was a Potemkin Village, littered with “junk machinery” and “trash.” “They appeared to be transparent, but they had fake transparency,” Mr. Block said. “The funniest thing was they had a large heap of scrap cardboard. They listed this on the books as raw material worth millions of dollars.” Shortly after the trip, Mr. Block wrote a sensationalistic report describing what he saw as fraud at Orient Paper and encouraged traders to sell shares of the company. He shorted the American-listed stock, which plummeted to around $4 from $15 in late 2010. Orient Paper called the report “reckless.” It also suggested that Mr. Block and his father had tried to extort money from the company before publishing the report. Mr. Block denied the allegation.

Since then, Mr. Block has issued damaging reports on other companies. He approaches each case like an investigation, sifting through corporate registration documents and even hiring private investigators to pose as potential business partners. “It’s amazing what edge you can get when you just read,” he said referring to company financial statements.

In the Sino-Forest case, he and his team of lawyers and private investigators spent two months poring over 10,000 pages of documents. His 39-page report concluded that Sino-Forest lied about assets and timber holdings. He posted photographs, charts and diagrams on the firm’s site in support of his claims. “As Bernard Madoff reminds us,” Mr. Block wrote in the introduction to the Sino-Forest research, “when an established institution commits fraud, the fraud can become stratospheric in size.” After the series of negative calls decimated the stocks of the Chinese companies, Mr. Block says he has received death threats and harassing phone calls and e-mails.

Critics of Block and other like him contend this emerging force has a financial motive to exaggerate and even fabricate information. Players like Mr. Block often place bets against the companies. The so-called short-sellers profit when the shares decline. Some fear their bearish research amounts to market manipulation. “There are fly-by-night analysts that are rumor-mongering because they are admittedly short the stock,” says Perrie M. Weiner, international co-chairman of the securities litigation practice at DLA Piper, who represents reverse-merger companies in regulatory disputes. “If you’re short the stock and you’re spreading negative rumors about the company, you better be right.”

Block said he would continue to publish his research. He says he believes investors and auditors need to understand how businesses operate in China. He explains by way of the firm’s name, Muddy Waters. It’s derived from a Chinese phrase that says the easiest way to catch fish is by muddying the water, forcing it to the surface. “You kick up the silt, and they rush to the top of the water,” he said of the Chinese proverb. “This explains a lot about how things work in China,” Mr. Block added. “Business deals are rife with value subtraction layers. The more opaque they make it, the easier it is for them to siphon off money.”

Chinese Reverse Merger Companies

Block has set his sights on a specific group of stocks that access the public markets through a back-door method known as a reverse merger. In such deals, private companies acquire a public shell company in the United States or Canada. They can quickly raise capital while avoiding the scrutiny and the cost of the traditional listing process. Today, there are more than 500 such Chinese companies in the United States, collectively worth billions of dollars.

After Block’s warning the Securities and Exchange Commission warned about the potential risks of investing in reverse-merger companies, including murky financials and complicated ownership structures. The S.E.C. says it has suspended trading on more than a dozen stocks in this category, which lacked “current, accurate information about these firms and their finances.” “This is an area of heightened scrutiny for us,” said Kara N. Brockmeyer, an assistant director in the agency’s division of enforcement.

Reforms of the Chinese Stock Markets

Until news laws were passed in 2007 individual and companies being investigated for insider trading and other violations could continue trading on China’s stock markets. Other reforms including improving credibility of market by requiring companies to give quarterly reports rather annual and semiannual ones.

In 2004, the government took control of five brokerages accused of engaging in illegal; trading . In the summer of 2006, Beijing allowed more than 1,300 listed companies to gradually sell their state-owned shares, effectively putting $270 billion in government-controlled assets in the public sector. These moves were though to be at least partly responsible for the booming market in 2006.

Many Chinese prefers try to get rich trading foreign currencies rather than buying stocks. Chinese individual investors have been allowed to trade in foreign currencies since 1992.. There are believed to be tens of thousands of ordinary Chinese that make wagers on foreign currency. In Beijing, there are 24-hour foreign currency trading centers to take their business. Until fairly recently they could buy yen, dollars, euros, Singapore dollars, Swiss francs, British pound, Australian dollars but not yuan.

The Growth Enterprise Board was set up in 2009 to help small private companies get finance.

In the midst of the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009, China’s State Council approved plans to allow margin lending and short-selling.

China to Ban Stock, Futures Trading on Unauthorized Exchanges

In November 2011, Bloomberg reported: China will ban trading of securities and futures on unauthorized exchanges to regulate the market and prevent financial risks, the State Council said. Some of the trading activities have led to price manipulation and fund embezzlement by the exchange managers, China’s cabinet said in a statement dated yesterday. Such problems may cause regional financial risks and endanger social stability, the statement said. [Source: Bloomberg, November 24, 2011]

There are over 300 unregulated bourses across the country, the Financial Times reported today, citing analysts. Turnover on the three authorized commodity futures and a financial futures exchanges in China fell 4 percent to 113.4 trillion yuan ($18 trillion) in the first ten months from a year ago, according to the China Futures Association.

“Regulators are concerned because these exchanges do not pay much attention to risk control, and volatile trading could hurt the participants and have a spillover effect on other companies and related industries,” said Shen Zhaoming, a Shanghai-based analyst at brokerage Changjiang Futures Co. “Local governments all hope for bigger economic influence, and they think establishing such exchange platforms is an efficient way to achieve the goal.”

Apart from the stock and futures exchanges approved by the State Council, no other bourses are allowed to list new shares, offer centralized pricing or make markets, the statement said. Exchanges that trade gold, insurance or credit products must receive approvals from financial authorities under the State Council, it said.

Local governments should set up teams immediately to “clean up and consolidate” the exchanges in their regions and rectify illegal trading activities of stocks (SHCOMP) or futures, the statement said. The use of the name “exchange” in Chinese will be strictly regulated, it said.

Image Sources: Tropical Island; Buying China Trends; China Daily

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012