LABOR AND WORKING CONDITIONS N CHINA

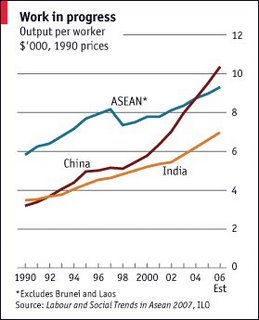

Workers get a relatively small piece of economic pie: 53 percent in 2007, down from 61 percent in 1990 and compared with two third in the United States. Total Workforce: 795.3 million in 2006. Labor force by occupation: 24 percent industry; 35 percent agriculture; 31 percent services (2005). By 2030 40 percent of the global work force will come from China or India.[Source: The Economist]

China once boasted it was a workers paradise. Under Communism, the most basic social divisions were between the peasants, mostly subsistence farmers bound to the land, and urban people who worked in factories and in the bureaucracy Modern China has been called “a giant labor-intensive processing factory.” Many Chinese still work for the state but their numbers are shrinking while those in the private sector are rising. The vast majority of jobs are created by the private sector.

China has difficulty creating jobs for new job seekers that enter the labor force every year. Measures to deal with the problem include encouraging more start ups and providing retraining for workers with outdated skills. Growth has to produce 24 million jobs a year to sustain the pace of migration. Before the economic downturns in the 2008 that appeared implausible. After that it seemed impossible.

One of China’s problems is that while it produces lots of low skill factory jobs it isn’t creating enough good job for college graduates. Many economists feel that China may be reaching the “Lewisian turning point” named after the late Nobel-Prize-winning economist Arthur Lewis who described how developing countries eventually exhaust their pool of cheap labor and have to evolve into a more developed economy.

PLA factory Labor is ruled by the same forces of supply and demand that govern consumption. At the moment China has a huge supply of labor so companies and employers can dictate the terms. If a worker is unhappy that pay is too low or the conditions are too harsh, he or she can easily be replaced: there are millions of other waiting in line for the job. The details of labor costs are a carefully-guarded secrets in China but analysts estimate that the wages and benefits per factory workers are about a tenth of what they are in the United States.

Ranking of education systems and worker productivity in Asia by Hong Kong-based Political and Economic Risk Consultancy: 1) South Korea; 2) Singapore; 3) Japan; 4) Taiwan; 5) India; 6) China; 7) Malaysia; 8) Hong Kong; 9) the Philippines; 10) Thailand; 11) Vietnam; 12) Indonesia

A study by the McKinsey Global Institute found that “fewer than 10 percent of Chinese job candidates, on average, would be suitable for work [in a multinational company] in nine occupations we studied.”

Chinese workers are becoming more efficient. Labor prices increased 15 percent in 2006 and 2007 but productivity increased even more, meaning that unit labor costs had decreased.

Websites and Sources: China Labor Watch chinalaborwatch.org ; China Labor Bulletin clb.org.hk/en ; China Law Blog on New Labor Laws chinalawblog.com ; Book: Understanding Labor and Employment Law in China (Cambridge University Press, 2009) cambridge.org/us ; Gloomy Photos of Workers zhouhai.com

Articles About LABOR IN CHINA factsanddetails.com MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China ; LABOR-INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

Books on Labor in China

“Working in China: Ethnographies of Labor and Workplace Transformation” (Routledge 2007; edited by Ching Kwan Lee) and “How China Works: Perspectives on the Twentieth-Century Industrial Workplace” (Routledge, 2006; edited by Jacob Eyferth) contain several commendable portraits of Chinese labor based on ethnographies and participant-observation by the authors. They have numerous chapters that explore workplace conflict and community (in sites ranging from department stores to merchant marine vessels to insurance sales agencies) and connect these issues to broader questions of power, culture, and political economy In a similar vein, Calvin Chen’s Some Assembly Required: Work, Community, and Politics in China’s Rural Factories (Harvard University Press, 2008), based on his experience of working and living at two township and village enterprises (TVEs) in Zhejiang province, offers rewarding insights into how workers experience and interpret multiple meanings of labor, and how these change over time. [Source: Mark W. Frazier, China Beat, July 2, 2010]

“Dorothy Solinger’s “States Gains, Labor’s Losses: China, France, and Mexico Choose Global Liaisons, 1980-2000" (Cornell University Press, 2010) provides, as its title reveals, a valuable analysis of how China’s labor unrest and government responses to it compares with two other countries where states have both pulled the plug on longstanding labor policies and quickly needed to respond with new welfare measures and increased social expenditures.

Books by journalists who have turned their focus to workers and factories in China are also excellent sources for understanding contemporary Chinese labor issues. The personal portraits of the subjects found in Leslie T. Chang’s Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (Spiegel & Grau, 2009) and in Alexandra Harney’s The China Price show how migrant workers experience the labor market of the sunbelt, and how they preserve ties to their home communities and to one another.

Working Conditions in China

Employers routinely discriminate on the basis of height, looks, health, home province and age. Workers are routinely passed over because they are too ugly or too short or have had hepatitis in the past. A typical advertisement for a factory job reads: “1) Age 18 to 35, middle school education, 2) Good health, good quality, 3) Attentive to hygiene, willing to eat bitterness and work hard. 4) Women 1.66 meters or taller. 5) People from Jiangxi and Sichuan need not apply.”

Factories often have a high turnover. Workers often quit. Companies traditionally could easily fire workers. Many workers have mobile phone and use them to exchange information about jobs. Workers that quit typically don’t give any notice when the leave. They typically ask for a couple days off, change their cell number and split. People frequently change jobs around the lunar New Year. New labors laws make it harder to fire workers.

Many jobs require a lot of overtime. Workers often welcome it as a chance to make more money. Sometimes workers go months without getting paid. When they lose their jobs they often don't receive the pension or severance pay that has been promised them.

Wages are low but so too is the cost of living, On a wage of $125 a month the owner of a violin factory told the Los Angeles Times, “China is poor. Everything is cheaper. With this money they can eat well and pass their lives well.

In a survey by Pew Research Center in 2008, 60 percent of those asked said they were satisfied with their jobs and 54 percent were satisfied with their household incomes.

See State Jobs, Types of Jobs

Wages, Work Week and Vacations in China

The average wage at a Chinese factory in 2009 was around $200 a month, 17 percent more than the year before. The average monthly of wage of China’s factory workers increased 66 percent between 2004 and 2007 to $234, about twice the rate of workers in Indonesia. High growth rated in China has allowed workers to receive double digit pay increases each year.

Work week: 42.4 hours, compared to 40.3 hours in France and 55.1 hours in South Korea. [Source: Roper Starch Worldwide, based on interviews in 2001 and 2002]

There are no reliable figures of average wages. Wages in northern China are as much 20 percent lower than those in southern China. Hourly labor costs: 1) China ($0.6); 2) India ($1.0); Czech republic 3) ($5.2); 4) Britain ($19.5); and 5) the United States ($21.6). Average hourly wages in Asia (1997): 1) $0.40 in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; 2) $0.90 in Shanghai, China; 3) $1.30 in Manila, the Philippines; 4) $1.80 in Jakarta, Indonesia; 5) $3.00 in Bangkok, Thailand; 6) $4.60 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 7) $6.20 in Seoul, South Korea; 8) $7.30 in Hong Kong; 8) $7.50 in Taipei, Taiwan.

Many Chinese get bonuses around the time of the lunar New Year and the “golden week” around the anniversary of the 1949 Communist Revolution. Many Chinese take off from work during the three "golden weeks": 1) around May Day on May 1st, in which Chinese get three work days off; 2) around National Day on October 1st; 2) and around Spring Festival (late January or early February).

Rather than asking how many days of vacation they get, many Chinese workers ask how many days they can work: they are motivated to make money and get ahead any way they can.

According to a survey by Japanese foodmaker Ajinomoto, working people in Shanghai got more sleep (seven hours and 28 minutes) than working people in New York, Paris and Stokcholm. People in Tokyo get the least sleep (slightly less than 6 hour a day). In New York the business people surveyed got six hours and 35 minutes. "In Shanghai, people simply seem to go to sleep earlier. Everyone in all the cities gets up around the same time in the mornings, between 6:30 and 7:00," said a Ajinomoto spokeswoman.

Wages as a proportion of China's GDP growth has been decreasing for over two decades, Zhang Jianguo, an official with the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), told workercn.cn, a website under the group. The proportion peaked at 56.5 percent in 1983, but it fell to 36.7 percent in 2005 and has not improved the report said.

Raising the Minimum Wage in China

When the Chinese government introduced the minimum wage in 2004, factory owners used it as the basic wage for their production-line workers.

In June 2010, while China was experiencing a number of labor problems, including disputes and suicides, the Beijing city government raised the minimum wage by 20 percent to $141 a month. [Source: Reuters, June 4, 2010]

Provinces and cities throughout the country have raised their minimum wage this year as companies have reported growing labor shortages with migrant workers from the interior choosing to seek jobs in small cities closer to their homes.

A strike at a Honda Motor car parts factory that began month was resolved Wednesday after the company offered its workers a 24 percent pay raise, showing how the balance of power in the country’s factories is gradually tipping toward workers. tung by labor shortages and a rash of suicides at its factories in southern China, Foxconn Technology has raised the salaries of many of its Chinese workers by a third.

In December 2010, China raised the minimum wage in Beijing by 20 percent for the second time in six months as adjustments for high food and property prices and to narrow the gap between rich and poor. The minimum monthly salary was raised to 1,160 yuan ($175) from 960 yuan.

Pressure for Higher Wages in China

High manufacturing job growth and highly-publicized strikes at Honda and Toyota plants and suicides at Foxconn factories in China put pressure in manufacturers to raise wages. Huang Yiping, an economic professor at Peking University told Bloomberg, “Honda’s just the tip of the iceberg, and it reflects an urgency of adjusting China’s growth model. After three decades of rapid growth partly driven by cheap labor, China must adjust to higher wages.

Tao Dong, an analyst with Credit Suisse, told Bloomberg, “I expect double digit wage growth a year over the next few years...Events have dramatized the beginning of the end of an era of China as world factory.” Chaing Kai, a director at Renmin University Labor Institute told Newsweek, “Our economy can’t keep squeezing labor benefits because workers are not willing to accept it.”

A survey in nine Chinese provinces by China’s central bank in 2010 found that a quarter of those that responded expected pay raises of at least 10 percent in 2010. Analyst expected this trend to continue for several years.

Wages are increasing but aspirations and expectations are growing even faster. Some expect the power of unions and collective bargaining to rise.

Companies are aiming to stay ahead of the trend by moving inland to cheaper areas or in other developing countries. Some of even returning back home to the West. General Electric, L’Oreal and New Balance are among the companies that are looking to Vietnam, Indonesia and other countries as labor sources.

Minimum Wage Raised in Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen

In early 2012, Bloomberg reported: Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen boosted their minimum wage as policy makers seek to spur consumer spending and a shrinking labor surplus pushes up salaries. Shanghai, the nation’s most affluent city, increased the wage by 13 percent to 1,450 yuan ($230) a month starting in April, the Shanghai human resources and social security bureau said. It’s the 19th adjustment since the city’s minimum wage rule was established in 1993, according to the statement. [Source: Bloomberg News, February 28, 2012]

Policy makers in the world’s second-biggest economy are trying both to keep inflation in check and shift the nation’s economic growth toward domestic demand. Promoting consumption by raising wages would facilitate such a transition, said Tim Condon, chief Asia economist at ING Financial Markets in Singapore. Increased company profits over the past decade “means producers have the wherewithal to increase salaries,” Condon said.

In 2011, 24 provinces and municipalities raised minimum wages by an average of 22 percent, according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Shanghai’s rose by 14 percent. China plans to raise the level by an average of at least 13 percent annually from 2011 to 2015, according to the national 12th Five-Year Plan that covers those years. The government suspended increases in minimum wages in 2009 to help companies weather the global financial turmoil. Thirty provinces raised minimum wages in 2010 by an average of 22 percent. Beijing, Shenzhen

Shanghai has a population of 23 million. Beijing, the nation’s capital with 19.6 million people, raised the minimum wage by 8.6 percent to 1,260 yuan a month on Jan. 1. Shenzhen, a manufacturing hub of 13 million people bordering Hong Kong, increased minimum payments by 13.6 percent in February. The southern region of Guangxi increased its wage by about 22 percent in January.

Foxconn Lifts Wages

In February 2012, The Guardian reported: Foxconn, the Taiwan-owned manufacturer with giant assembly facilities in mainland China which is one of Apple's main contractors, says it has raised wages by up to 25 percent in the second major salary hike in less than two years. As the world's largest electronics contract manufacturer, it has come under intensive scrutiny after a spate of suicides last year and reports of long hours for the hundreds of thousands of staff. Its facilities are scheduled for inspection by a team from the US Fair Labor Association, at the prompting of Apple. [Source: The Guardian, Charles Arthur, February 20, 2012]

Foxconn employs about 1.2 million workers at a handful of massive plants in China which are run with almost military discipline, in which staff work for six or seven days a week and up to 14 hours per day. The workers assemble iPhones and iPads for Apple, Xbox 360 video game consoles for Microsoft, and computers for Dell and Hewlett-Packard. Foxconn is one of China's largest single private employers.

Chinese workers at Foxconn now receive between 1,800-2,500 yuan ($286-$400) per month following the raises that became effective from 1 February, the company said. "This is the way capitalism is supposed to work," David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the New York Times . "As nations develop, wages rise and life theoretically gets better for everyone. "But in China, for that change to be permanent, consumers have to be willing to bear the consequences. When people read about bad Chinese factories in the paper, they might have a moment of outrage. But then they go to Amazon and are as ruthless as ever about paying the lowest prices."

Foxconn is also taking measures to limit workers' total work hours. The raises come as a compensation for their reduced overtime, company spokesman Simon Hsing said in a statement. Foxconn said it is cooperating with the FLA inspectors, pledging again to provide a safe and fair work environment.

The company has denied allegations that it ran excessively fast assembly lines and demanded too much overtime, but after the suicides it soon announced two pay hikes that more than doubled basic worker salaries to up to 2,000 yuan per month. In January 2012 dozens of workers assembling video game consoles climbed to a Foxconn factory dormitory roof in the central Chinese city of Wuhan and some threatened to jump to their deaths amid a dispute over job transfers that was later defused.

The New York Times reported that workers welcomed the announced raises and overtime limits, though some were unsure they would cause much real change. "When I was in Foxconn, there were rumors about pay raises every now and then, but I've never seen that day happen until I left," said Gan Lunqun, 23, a former Foxconn worker. "This time it sounds more credible." "China can't guarantee the low wages and costs they once did," Ron Turi of Element 3 Battery Venture, a consulting firm in the battery industry, told the paper. "And companies like Foxconn have developed international profiles, and so they have to worry about how they're seen by people living in places with very different standards." Foxconn has also announced plans to invest in millions of robots and automate aspects of production.

Overtime Pay and Severance Pay in China

A common complaint among laborers is lack of overtime pay when a work schedule exceeds 40 hours. Liu, the labor advocate, said his group had done a study of 210 factories in the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta that showed 90 percent of those factories cheat on overtime: they often reported employees as working eight-hour days even when the hours were much longer. Thus, the salaries were much more generous on paper than in reality. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, June 20, 2010]

At the Gloria Plaza Hotel in Beijing, workers took their dispute with management to the streets on May 2010. The company that owns the hotel plans to tear it down and lay off the workers. Although the company had said the workers would get the minimum severance pay required by law, the employees complained that that was far too low. They are a state-owned enterprise, they have the money, but they don’t care about us at all, said one woman who declined to be named for fear of retribution.

Chinese Workers

China has traditionally had an obedient work force, which helps keep management costs low. Photographs of Chinese factories often show rows of workers with no supervisors in sight. In some work places it is not uncommon to have only 15 mangers for 5,000 workers. Working together is expressed by the Chinese proverb: Eight hermits sail the ocean with the might of each other.

A study by the McKinsey consulting group found that the average Chinese workers needs to put in seven hours on the job to earn enough to purchase the same amount of goods or services that an American worker could buy with one hour’s pay.

It’s not only cheap labor that drives China’s economy. Chinese workers are hard working and efficient. Marril Weigrod, a consultant for China Strategies, told the New York Times: “Culturally the Chinese put a very high premium on not losing face. In manufacturing, that translates into not making mistakes on the production line. Their self-discipline and their ability to adapt are key factors in driving Chinese competitiveness.” If one worker is not up to snuff there is another worker waiting in the wings to take his place.

One businessman told Theroux that "young workers were lazy, slow and arrogant, while those over fifty were the best.” Workers who grew up during the Cultural Revolution "seem to have a chip on their shoulder, as if they were cut out for better things." The Chinese "are used to working with their hands," he added. "That's the problem. They can rig up something with a piece of wire and a stick. But they have never relied on sophisticated machinery or high tech. I have to show them every detail about a hundred times." One worker with a machine-making company I talked to said the Chinese were not very good at tinkering with machines to work out what is wrong with them.

Motivated and Hard-Working Workers

On China’s labor force, Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “The sheer human energy is overwhelming: the fearless entrepreneurs, the quick-moving builders, the young migrants. Virtually everybody has been toughened by the past; families remember well the poverty of the Mao period. Meanwhile most Chinese have seen their living standards rise in recent years, often dramatically. This combination — the fear of the past, the opportunities of the present — has created a uniquely motivated population. It’s hard to imagine another place where people are willing to work.”

On workers in Lishui, a small industrial in Zhejiang Province, Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “I was impressed by how comfortable people were with their jobs, They didn’t worry about who consumes their products, and very little of their self worth was tied up in these trades...If a job disappeared or an opportunity dried up, workers didn’t waste time wondering why, and they move on. Their humility helped, because they never viewed themselves as being the center of the world.”

“In Lishui people moved incredibly fast with regard to new opportunities. This quality lay at the heart of the city’s relationship with the outside world. Lishui was home to the greatest number of pragmatists...everybody was so opportunist in the purist sense. They market taught them that — factory workers changed jobs frequently, and entrepreneurs could shift their product lines at the drop of a hat.” Hessler came across one family that over the course of a few months sewed colored beads onto children’s shows, applied decorative strips to hair bands, assembled small light bulbs and finally bought some second hand computers and played World of Warcraft for money as “gold farmers.” [Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, October 26, 2009]

There are plenty of opportunities for advancement in China. It is easy to change jobs or start new businesses. Factory workers can triple there incomes by taking computer courses or learning a little English. Unabashed ambition and live-for-today opportunism are what drive people rather than traditional Confucian values

Work Exercises in China

Radio calisthenics is the name of the twice-daily fitness broadcasts that reached their participatory peak in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution. The first broadcast is in the morning to make sure workers get their day off to a good start. The music and routine are set and almost every Chinese has learned it in school. [Source: John Glionna, the Los Angeles Times, September 14, 2010]

Over the years people lost interest in the routine and employers didn’t bother to push it as they once did but in recent years radio calisthenics have made a comeback. Describing the scene before the opening of a department store in Beijing John Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Wearing her form-fitting skirt and high heels, the 24-year-old cosmetics clerk joins her coworkers for eight minutes of semi-strenuous exercise: a sort of office-place Rockettes routine that is spiced by Far East martial arts moves, peppy music and precise instructions broadcast over state-run radio.”

Formally known as Dance Routine No. 8 the routine was introduced in 1951 and has been updated every five to 10 years. Music and instructions are broadcasts at 10:00am and 3:00pm over state-controlled Beijing Sports radio. Some do the routine in parking lots or other outside open areas; others do it indoors.

In 2011, the Chinese government plans to make the daily exercise routine compulsory for all employees at state-owned enterprises. Some say that government is reviving the practice to fend of the negative aspects of increased prosperity, junk food and a couch potato life style. Others assert it is the government’s way or reasserting control over the lives of individuals. One official told the China Daily, “Any exercise done by the individual can be tedious and boring...Through collective [exercise] people feel more relaxed and have greater efficiency at work. That’s why we want to resume the fitness activity.”

Many Chinese roll their eyes at the idea of being forced to do the exercise routine. One worker told the Los Angeles Times, “People secretly admit they don’t want to do it. They say it’s childish. It’s not cool.” An Internet blogger wrote: “This is all connected to the singing of revolutionary anthems. It totally shows that history is moving backward.”

Nationalism, Stress, and Work in China

One Japanese manager in China told the Washington Post, “The competition for jobs is really brutal here, so people are far more serious about their work..” In Japan “we have to promise workers jobs for life and pay them based on seniority. But no one even thinks about that here. Workers in China believe in merit.”

The stress created by free market economics seems to be taking its toll. One survey found that a third of all this asked felt angry, frustrated or listless. Prozac sales nearly doubled between 2000 and 2004 and an increasing number of stressed out Chinese are seeking advise from psychologists and counselors.

It is not uncommon for discouraged officials and managers to commit suicide. See Mattel

Employers try to boost production from their workers by encouraging nationalism. A sign outside the Chery automotive plant reads: “We Need Not Only to Work Hard, We Must Also Be Diligent, and More Important We Must Have a Sense of a National Mission.”

Overworked Chinese White Collar Workers

Many young Chinese professionals feel burned out, empty and numb. Sim Chi Yin wrote in The Straits Times, “Almost as soon as he wakes up at 8am each day, property agent Kevin Tu is already tired. He drags himself to work, and puts in nine hours in front of the computer and with clients. Then he goes home to his one-bedroom apartment in the south side of Beijing to stare at TV shows alone. A go-getting executive in a multi-national company just a few years ago, Tu, 31, now lives just "one day at a time", as he puts it. [Source: Sim Chi Yin, The Straits Times, September 13, 2010]

There are no known academic studies on this phenomenon, but the magazine cited a survey carried out last year by The Beijing News newspaper and Sina Web portal of 1,700 people across China. It showed that 70 per cent of them displayed signs of job burnout. Almost 60 per cent of the companies polled also said that the incidence of burnout among their employees had increased.

Just last week, the official People's Daily reported that the burgeoning ranks being labelled 'middle class' in China are battling daily worries about paying for a house, car and credit card bills. "Young Chinese feel suppressed by pressure on many fronts," said professor Zhou. "Once they graduate, they have to fight to find a job, make enough money to buy a home amid soaring property prices, and once they do that they are in debt for a long time." "My generation had more ideals, more room to fulfil those ideals," he added.

The root source of these woes is the great inequality in Chinese society today, he said, noting that powerful elite interest groups keep a stranglehold on wealth. "In China, if you're not born into the elite, then you're just unlucky for life," professor Zhou said. For his part, Tu is concerned less with money than about finding his zest for life again. "Maybe this numbness is just a phase," he said, thinking aloud. "Or maybe life will just be this bland for me and I'll just have to accept that this is it."

China’s Plasticine Men

The growing group of fatigued young, white-collar Chinese are known as 'eraser' or 'plasticine' men (xiang pi ren). Sim Chi Yin wrote in The Straits Times, “Brow-beaten out of shape by life, they show little if any response as they are kneaded this way and that, reported a local news magazine which has popularised the term now spreading in Chinese cyberspace. Broadly defined, they are mostly white-collar workers who are somewhat numb to life, have no dreams, interests or ideals, and do not feel much pain - or joy - reported the Guangzhou-based New Weekly magazine. [Source: Sim Chi Yin, The Straits Times, September 13, 2010]

These 'plasticine men' can be found among doctors, bank employees, teachers, journalists, traffic policemen, civil servants, actors and taxi drivers, the magazine reported. Typically, they work alone and for more than 50 hours a week. They feel as if they have expended all their energy and all they get in return is a sense of emptiness.

The term comes from a 1986 book, Xiang Pi Ren (Plasticine Man), by still-popular novelist Wang Shuo, that was later made into a film entitled Out Of Breath (Da chuan qi). It tells the story of a plucky young man who arrives in the southern economic powerhouse of Guangzhou with lofty dreams. Cheated many times over in business, he ends up in jail where he is repeatedly beaten up by fellow prisoners. He is left indifferent and dehumanized, feeling nothing when he discovers his lover has long been stringing him along.

That fictional depiction might be a tad dramatised, but soulless white-collar Chinese workers who feel entrapped in this pressure-cooker society are not difficult to find. While he is not depressed and surrounds himself with friends, Mr Tu said he feels much like a 'plasticine man'. "Everything just feels very bland," he said. "I have no ambition, no real goal in life and I just don't feel interested in anything anymore, even in hobbies I used to have." The native of Wuhan city in central China lives in Beijing alone. Most Chinese men his age would be married and about to start a family, but Mr Tu said: "Now that I feel stuck in my career, I am in no mood to look for a mate."

If there is a growing group of 'plasticine men' among China's white-collar class, it is hardly surprising, said outspoken sociology professor Zhou Xiaozheng of Renmin University in Beijing. "We are all slaves these days. Buy a house and you're a 'house slave' (fang nu). Buy a car and you're a 'car slave' (che nu). Bear a child and you're a 'child slave' (hai nu)," he said.

Job Searching Customs in China

Looking for work in Guangdong

In the Maoist era, the government fen pei system guaranteed jobs to everyone. People had no real say in where they worked: they were told by the government where to work. The best jobs tended to go to those with best connections with the Communist party. One think tank researcher told the Los Angeles Times, "In 1985, you sat in school and waited for a teacher to tell you, 'This work unit has this many openings,' and what kind of jobs you should look for.'"

People no longer wait for job assignments. They now have to go to job interviews. College graduates tend to get jobs more through their connections that abilities, test scores work experience and letters of recommendation. A university faculty advisors is instrumental in getting someone a job.

Even so many private companies today, especially those that deal with foreigners, are hiring new employees on the basis or merit and experience. The process that college graduates go through to find work’submitting resumes, attending job fairs and going to interviews — is becoming more and more like what their American counterparts go through. Many people look for jobs at job fairs known as talent markets.

Height, marriage status, age and health record can all be taken into consideration by potential employers. People have been denied jobs because they have had hepatitis in the past or are too short. Companies often refuse to hire workers who over 35 and 40. But because of the one-child police the number or workers in the 20 to 24 bracket is already starting to shrink.

People applying for jobs routinely lie to their prospective employers. One government investigation uncovered that 15,000 civil servants had used fake university degrees or bogus certificates to get their jobs. Lying about credentials is such a problem that companies can hire investigators that specialize in checking out if credentials claimed by applicants and staff members are for real.

Looking for Work After Graduation, See Education

'Naked' Resignations on the Rise

Wang Wen wrote in the China Daily, “When Song Lin submitted her resignation on New Year's Eve her boss asked whether she had received a job offering better pay. "I don't actually know what I will do after quitting," Song said. "For this reason, I didn't even tell my parents about my decision. I just know that job was not for me." Song, who had spent the last two years working for a company based overseas in what was her first job, said she is more interested in organizations rather than business. She is prepared to wait several months for the ideal job to arrive and has savings that will support her for at least a year. [Source: Wang Wen, China Daily, January 31, 2012]

The white-collar worker is not alone in China in quitting a job before getting a new one, according to the latest job-hunting research. It identified a growing trend for younger people to put their ideals ahead of work as the country undergoes a radical transformation from an export-driven manufacturing economy to a more innovative business model. Job analysts call the trend "naked" resignation. It started to become common in 2011, according to the annual employment report by 51job Inc, one of the biggest human resource service companies in China.

A more liberal and independent generation of workers, like Song, are less likely to be lured by income. Instead, they want a more rewarding life experience that gives them peace of mind, according to specialist observers. They are no longer afraid to leave traditional career paths if they find them to be less rewarding than they hoped. They see abundant opportunities but also less job security. This trend is changing the landscape of China's job market and making it more favorable for employees.

More than 80 percent of surveyed employees said they wanted to change their current jobs at the end of 2011. "The young generation seems more distant toward the traditional job market," said Feng Lijuan, chief human resources consultant at 51job Inc. "There is a growing trend that jobs are less important in the lives of workers. They seek more equality in the job market and greater job satisfaction, both mentally and materially." For Li Chen, managing partner of Apex Recruiter Ltd, a headhunting company in Beijing, about 30 to 40 percent of his candidates resigned "naked". "These candidates care about opportunities and career development rather than salary," said the veteran headhunter.

A growing number of experienced workers are also lured by opportunities outside business capitals such as Beijing and Shanghai, according to the latest analysis. Second- and third-tier cities in China, although less developed than the first tier, offer more freedom for workers who seek to make a bigger difference in their career paths. It is the chance to be a big fish in a smaller pond.

This new generation downplays the importance of work and is acutely aware of the dangers of overwork. A growing number of employment injuries and death caused by working too hard lie behind a desire to play safe and quit jobs with nothing to go to. "Employers are also paying more attention to their health," said Xie Zheng, China partner of Antal International, a British-based recruitment company.

China's high inflation rate last year also made life harder for employers, many of whom felt obliged to raise wages to keep staff despite the economic slowdown. "Some employers raised salaries by up to 30 percent but still couldn't stop their employees from leaving or attract new recruits," said Feng Lijuan. Vacancies in the job market have risen more than 30 percent but the number of applicants is up just 12 percent, according to statistics compiled by Zhaopin.com, another major human resource service in China.

The current lack of job applicants is forcing employers to be more aggressive in headhunting, analysts said. The first pay rises are often given to shopfloor staff and specialized workers. The job market in China is also witnessing the first signs of a scaling-back in job recruitment in the face of higher wages in comparison with Southeast Asian countries. The trend is further transforming China's job market from a labor-intensive one to a more mature one, analysts said.

Moonlighting in China

Many people have two or three jobs and earn extra money taking short term assignments, temporary work. A lot of money is earned under the table and off the books, and boosting incomes to higher levels than those recorded in official statistics.

State jobs pay very little. They pais so little in the 1990s it was not uncommon for university professors and doctors to moonlight as by driving a taxi, shining shoes, waitressing to their bills, or write articles for popular magazines, teach English or aerobics, consult on computer programs or give seminars on stocks and bonds to earn extra money.

"The biggest difference," one man told Theroux of China after the Deng reforms, "is that we can all get jobs now. In the past if you didn't have a job you stayed at home. The government gave you nothing and you had to take money from your parents. Now everyone can find something to do. There is plenty of work."

Female factory worker

Cheap Labor in China

An executive at Volkswagen once said "the cost of labor in China is nothing." By one count there are 760 million laborers in China. One Chinese analyst predicted that China would be the main source of cheap labor for the next 30 to 60 years.

Female textile workers in Guangdong make $60 to $150 a month. A worker who has put in 30 years at a pencil factory in Shanghai earns about $75 a month with bonuses of $35 a month for high productivity. An elevator operator in Beijing makes $35 a month and no benefits. Workers jump at the opportunity earn $60 a month because all they can earn at home as farmer is around $20 a month. A typical job in the countryside is mixing mud and water for 10,000 bricks for 25 cents.

Expenses for low-cost labor are low. Many factories provide room and board. Fifty cents will buy a worker a large plate of rice at a restaurant near his factory. Many workers are by piecework, with workers getting paid for each until they produce, If they work hard and their si enough work the can make $100 or $150 a month but often the make less than $50 a months.

Many migrant speak mutually unintelligible dialects. Large factories often have separate cafeterias that serve dishes native to different regions.

There is cheaper labor in Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia and Myanmar. Monthly wages in 2000 were $65 in China, compared to $30 in Indonesia, $42 in Vietnam. Cheap labor in China is considered better than cheap labor in other places because of the quality and dedication of the workers and management.

Low labor cost have taken jobs away from other countries around the globe where labor and benefits costs are higher. In many cases, Chinese companies using manual labor for jobs done by machines overseas. But As labor costs rise in China factory owners are taking their businesses to places such as Vietnam. In November 2007, the American toymaker Tomy, which makes 90 percent of its toys in China, announced it cut production in China by a third because of surging labor costs and move production to other Asian countries, most likely Thailand and Vietnam.

Globalization and Labor in China

Among the works that show how China’s openness to foreign investment brought institutions that replaced Maoist or socialist labor practices with labor law, employment contracts, and dispute resolution are Mary E. Gallagher’s “Contagious Capitalism: Globalization and the Politics of Labor in China” (Princeton University Press, 2005). Gallagher shows that timing was everything: foreign direct investment coming to China in the 1980s created a laboratory for the reform of labor practices, and in the 1990s the politically sensitive reforms to China’s domestic or state-owned enterprise sector could commence as this sector adopted the labor contracts and workplace norms found in the foreign-invested sector. Not that the process went smoothly, but the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership managed to prevent the formation of a broad-based opposition movement made up of laid-off workers. [Source: Mark W. Frazier, China Beat, July 2, 2010]

The extent to which global capitalism influences labor in China is also a theme found in The China Price: The True Cost of Chinese Competitive Advantage (The Penguin Press, 2008) by Alexandra Harney, a Financial Times reporter. Among much else, Harney’s book shows how the regime of factory inspections by NGOs and other international labor rights auditors is hampered by the way in which factory owners take a clue from corrupt accountants by keeping two sets of factories — one for showing to the auditors, and one for where the actual production takes place, with rampant labor violations and abuse.

Foreign Workers in China

An increasing number of illegal immigrants from countries poorer than China, seeking higher wages and a better life than they can get at home, are entering China. They come from Southeast Asia, North Korea and even as far away as Africa. In some cases it easy for them to get in as there are virtually no fences along China’s 20,000-kilometer-long border. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, September 2010]

Many are surreptitiously crossing the border from Vietnam. One Vietnamese clothing merchant who travels regularly between China and Vietnam told the Los Angeles Times, “people are struggling for money in Vietnam. They look at China and think it’s rich. In China they can find a job easily and earn so much more.” A typical laborer from Vietnam is between 17 and 20 years old and is brought into China by guides and agents who are paid around $30 per head by an employer. Near the Vietnamese border they often do field work for $5 a day (Chinese get $9 a day for the same work) and often do work that no Chinese is willing to do.

One agent told the Los Angeles Times that the government “won’t ever be able to control the border. There are too many small roads and passes. Besides who else is going to work in the fields?” The immigrants from Vietnam don’t look so different from Chinese and members of ethnic groups found in southern China. Some speak Cantonese, which helps in the industrial areas around Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

Legal foreign workers are few and far between. The government doesn’t grant many work visas or residences to foreigners that lack specific skills. Officially businesses that hire undocumented aliens can be fined as much as $3,750. Workers can be fined $150 and be deported. There has been some violence involving foreign workers. In 2009, there was a small riot in Guangzhou after police were accused of harassing African merchants that left one Nigerian man dead.

Americans Seeking Employment in China

During the global economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 some Americans came to China to seek job opportunities. One West Virginia resident who can’t speak Chinese told AP, “I applied for jobs all over the U.S. There just weren’t any.” After coming to Beijing as an Olympic volunteer she said, in China “the jobs are easy to find. And there are so many.” Many foreigners get jobs as English teachers but some also get skilled positions in computers, finance and other fields.”

To hire foreigners Chinese companies need to explain why a foreigner is needed over a Chinese national but the government promises an answer within 15 working days, considerably shorter than the wait time in some countries.

About 217,000 foreigners held work permits at the end of 2008, up from 210,000 in 2007.

The State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs, a Chinese government agency, estimates there are 460,000 foreign professionals in China. There are so many and such a high demand for them there are even job fairs for them.

End of Labor Force Growth in China

If China ends up with too many old people and too few young workers it could slow economic growth. In the worst case the government and families will have to tap into savings to take care of the elderly, reducing funds for investments and driving up interest rates. As the working-age population shrinks, labor cost will rise. China’s aging population could undermine the advantages of low-cost labor by the middle of the 21st century. In 2007 China had six people in the workforce for every retiree but this ratio while fall to 2:1 by 2050.

Nicholas Eberstad wrote in Far Eastern Economic Review, “China's explosive economic growth between 1979 and 2008 was historically unprecedented in pace, duration, and scale. A repeat performance over the coming generation is most unlikely for one simple reason: the demographic inputs that facilitated this amazing first act are no longer available. [Source: Nicholas Eberstad, Far Eastern Economic Review, December 2009. Eberstadt holds the Henry Wendt Chair in political economy at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and is senior adviser to the National Bureau of Asian Research]

Over the 1980-2005 generation, China's working-age population — defined here as the 15- to 64-year-old group — grew by about 2 percent per annum. Yet over the coming generation, China's prospective manpower growth rate is zero. By the “medium variant” projections of the United Nations Population Division (UNPD), the 15- to 64-year-old group will be roughly 25 million persons smaller in 2035 than it is today, and by 2035 it would be dropping at a tempo of about 0.7 percent per year. In fact, by the U.S. Census Bureau's reckonings, China's conventionally defined manpower will peak by 2016 and will thereafter commence an accelerating decline. Though these forecasts concern events far in the future, they are more than mere conjecture; virtually everyone who will be part of China's 15- to 64-year-old-group in the year 2024 is alive today. If current childbearing trajectories continue, by the UNPD's reckoning, each new generation will be at least 20 percent smaller than the one before it.

These numbers alone would augur ill for the continuation of rapid economic growth in China, but the situation is even more unfavorable when one considers the shifts in the composition of China's working-age population. In modern societies, it is the youngest cohorts of the labor force who have the best health, the highest levels of education, the most up-to-date technical skills — and thus the greatest potential to contribute to productivity. In China, however, this cohort has been shrinking for a generation, and stands to shrink still further, in both relative and absolute terms. In 1985, 15- to 29-year-olds accounted for 47 percent of China's working age population. Today that proportion is down to about 34 percent of the workforce. By Census Bureau projections, 20 years from now it will have fallen to just barely 26 percent of China's conventionally defined labor force.

The only reason China's working age population will not shrink more rapidly over the next few decades is because of an enormous coming wave of laborers in the 50- to 64-year-old age range. This group looks to swell by over 100 million between 2009 and 2029, growing from 22 percent of the working population to roughly 32 percent. The educational profile of this group is far more elementary than is generally appreciated: according to official Chinese census data, 47 percent of 50- to 64-year-olds have not completed primary schooling.

With this coming “age wave,” the structure of China's labor force will be inverted. A generation ago, there were nearly three times as many younger workers as older workers. Today there are half again as many younger workers as older ones. Two decades from now, the Census Bureau projects 120 older prospective workers for every 100 younger ones (at which point the situation may then stabilize, depending upon fertility trends). It's not exactly an ideal transformation in the labor force structure if one is aiming to maintain rapid rates of economic growth.

The situation might be easier for economic planners to cope with if China were still a nation with an abundance of underemployed labor. But policy makers in Beijing can no longer count on these once huge reserves. Instead, leading Chinese economists — among them Professor Cai Fang, director of the Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences — argue that the Chinese economy has already reached a turning point where those seemingly unlimited reserves of rural labor have actually been tapped out, and any future increase in demand for labor will only be supplied by increasing wages.

Shrinking Labor Population and Rising Elderly Population

China’s once cheap and plentiful pool of workers is becoming more scarce and expensive; the labor force declined by 3.45 million in 2012 and is expected to decrease by 10 million per year starting in 2025. The shrinking pool of workers will be forced to support an expanding population of senior citizens -- 200 million in 2013 -- that is expected to arrive at 360 million (more than the current U.S. population) in 2030. Meanwhile, over the next two decades, pension liabilities may reach more than $10 trillion.

From 2010 to 2030 China's working-age population—those ages 15 to 64—is expected to lose 67 million workers—more than the entire population of France—according to United Nations projections. Over that period, the elderly population is projected to soar from a tenth to a quarter of the population, according to U.N. data. China's population, the world's largest, rose to 1.34 billion in 2010, according to census data. It had been projected to peak at around 1.4 billion in 10 years but decline for the next 30. [Source: Laurie Burkitt, Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2013]

The Chinese birthrate has plunged to 1.18 births per woman, considered too low for the population to replenish itself. Many analysts say the one-child policy has shrunk China's labor pool, hurting economic growth. For the first time in decades the working age population fell in 2012, and China could be the first country in the world to get old before it gets rich. China's working-age population fell by about 3.45 million to 937 million in 2012. The drop added to concerns about how the country will provide for its 194 million elderly citizens, who now make up 14.3 percent of the population, a nearly three-fold increase from 1982. [Source: AFP, November 16, 2013]

Laurie Burkitt wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “Wang Feng, a demographer at Fudan University in Shanghai, and other population experts have argued for several years that the government was running out of time to change course. Birthrates had already fallen, in some cities to levels below that needed to replace the current population. If left unchecked, they said, the labor force would shrink, pressuring wages and inflation, and fewer workers would be taking care of a growing elderly population, potentially creating a pension shortfall.

“Companies manufacturing or operating in China have already seen their profits diminish as the supply of labor—seen as China's most competitive advantage in attracting foreign companies to its turf—tightens, pushing up wages. The predicament has caused experts to wonder if the world's No. 2 economy would grow old before it gets rich. Japan's long slump beginning in the 1990s occurred after a similar dip in demographics, though Japan was far wealthier at the time than China is currently and was able to absorb the slowdown in growth. Population experts said the latest move, while positive, fails to fully steer China away from the demographic crisis. "The entire policy should have been abolished," said Liang Zhongtang, a demographer from the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

Image Sources: 1) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; 2) BBC; 3,6 ) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 4) China Labor Watch; 5) Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china ; 7) Reuters, Telegraph

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2014