CHINESE LABOR RIGHTS AND UNIONS

Li Qian, head of China Labor Watch It is ironic that a nation founded on the Communist principals of sticking up for workers now neglects them. Independent trade unions are forbidden and abused workers generally have no legal recourse. Those that stick up for their rights are sometimes beaten up by thugs. Cadres and capitalists often have very close relationships and help to enrich each other.

With companies being increasingly concerned about their image abroad they are more willing to make changes and discuss problems with labor representatives.

An international meeting on workers rights and unions organized after much painstakingly work for December 2004 was abruptly cancelled at the last minute.

Good Websites and Sources: China Labor Watch chinalaborwatch.org ; China Labor Bulletin clb.org.hk/en ; China Law Blog on New Labor Laws chinalawblog.com ; Book: Understanding Labor and Employment Law in China (Cambridge University Press, 2009) cambridge.org/us ; Gloomy Photos of Workers zhouhai.com

Articles About LABOR IN CHINA factsanddetails.com MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China ; LABOR-INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

Chinese Labor Laws

There are laws that have been on the books since 1995 that promise workers a five-day, 40-hour work week, guarantee a minimum wage of at least $48 a week and require overtime pay for hours over 44 hours a week, and restrict overtime to 32 hours a month..

Labor laws designed to protect workers are probably ignored more than they are followed. Workers routinely work 12 hrs or more a day, often six or seven days a week. Even when authorities are aware of violations the laws are rarely enforced and when they are the punishments are light. Many factory owners skirt the laws by bribing officials. Many workers have no idea that the laws exist. Local and national labor laws are often contradictory.

It is illegal to hire workers younger than 16. Teenagers younger than that routinely borrow someone else identity card and lie about their age. It is a common practice and a neither potential employers or potential employees seems to qualms about it.

In 2006, a proposed labor law — the new Labor Contract Law — intended to address abuses, increase wages, reduce working hours to 40 hours a week and increasing overtime pay — was opposes by foreign corporations doing business in China. China’s existing labor law have already caused some foreign companies to leave China for other countries without such laws.

New labor laws implemented in 2008 requires employers to pay overtime, provide insurance and give laid off workers one month of severance pay for every year worked. The laws also make it harder to lay off workers. Credit Suisse estimates these laws add 15 percent to 20 percent to the cost of running a labor-intensive factories. The laws have also encouraged workers to stand up and fight for their rights, which in turn has encourage companies to follow the rules.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, "Labor laws, enacted in 2008, were intended to channel worker frustrations through a system of arbitration and courts so no broader protest movements would threaten political stability. But if recent strikes and a surge in arbitration and court cases reflect a rising worker consciousness partly rooted in awareness of greater legal rights, they also underscore new challenges in China. The labor laws have raised expectations, but still leave workers relatively powerless by Western standards. The Communist Party-run legal system cannot cope with the exploding volume of labor disputes. And legal enforcement by local officials loosened when the global economic crisis hit China and resulted in factory shutdowns." [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, June 20, 2010]

Chinese Labor Contract Law

Workers protest The Labor Contract Law enacted in January 2008 tries to guarantee contracts for all full-time employees, but leaves many details vague. Another law enacted in May 2008 helped streamline the system of arbitration and lawsuits, but civil courts and arbitration committees, which are made up of government employees, have been overwhelmed by a flood of cases. Meanwhile, because of lax enforcement, companies dodge other labor laws by cheating on minimum wage requirements and overtime pay.

The main goal of the Labor Contract Law has been to ensure that full-time employees across all industries work under a contract. It also tries to mandate severance pay for contracted employees. But companies find ways around contract guarantees or wage laws.

Publicity regarding the Labor Contract Law had a tremendous impact on raising worker consciousness, said Aaron Halegua, a lawyer based in New York who is a consultant on Chinese labor law. Even if migrant workers still do not know the specific details of each of their legal rights, far more came to realize that they have rights and there are laws protecting them.

Chinese Labor Unions

Chinese labor laws give workers the right to form unions. Trade unions are an arm of the state, and are controlled by and provide funding for the Communist Party. The party tells unions which leaders to elect. According to Chinese law a union can be created at any place with 25 or employees. The approval of the employer is not required. The unions do not negotiate and make agreements with state-controlled management.

It is estimated that just over 60 percent of companies in Beijing have a labor union, which is similar to the nationwide ratio in China. Chinese trade unions don’t negotiate contacts.By law all companies that have more than 100 employees are supposed to have unions but these are unions in name only. Most companies ignore the rule. When ones are set up they are often run by factory owners, the traditional adversary of unions, or local officials in cahoots with the factory owners. Rank-and-file members are expected to follow their orders. The union does little in the way of traditional union activities such as lobbying for better wages and better working conditions.

Unions are trying to organize at foreign-owned companies. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions has the goal unionizing 70 percent of foreign companies in China. In recent years it has focused its attention on unionizing workers at Wal-Mart (See Wal-Mart). There are about 670 Japanese-affiliated companies in Beijing, many of which are believed to have no labor union.

All-China Federation of Trade Unions

Under the current system, only the government-run union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, which has more than 170 million members, is permitted. The union only nominally represents workers; in practice, it has close ties with management. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, June 20, 2010]

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions is China’s state-sanctioned labor body. It is run like the Communist Party. Membership dropped from 130 million in 1990 to 90 million in 2000. It also has trouble recruiting new members.

The state-backed unions are largely charged with overseeing workers, not bargaining for higher wages or pressing for improved labor conditions. And they are not allowed to strike, although China’s laws do not have explicit prohibitions against doing so.

The union has a wide presence in state-owned companies and has made a big push to establish branches in foreign companies — its most notable victory was unionizing Wal-Mart stores in 2006. Private Taiwanese, Hong Kong and mainland Chinese companies often do not have branches of the official union. Marc Blecher’s 2008 article in Critical Asian Studies (When Wal-Mart Wimped Out) interprets the significance and considerable irony of the ACFTU’s decision to compel the world’s largest corporation and outspoken opponent of unions to organize ACFTU branches in its sixty stores in China.

Independent Trade Unions in China

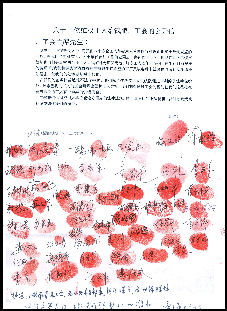

Suit with thumbprints by

workers at a fertilizer factory

Chinese workers still do not have the right to form unions independent of the one controlled by the government. Independent trade unions are illegal and regarded as a threat to the Communist Party. Efforts to set up unions are crushed by police. Leaders have been arrested and given long prison sentences. These days agitators are getting away with more than they used. In some cases they have pushed companies to set up union but were then left of the list of candidates to run it. In October 2003, Li Jianfeng, a former court official was sentenced to 16 years in prison subversion for attempting to start an independent trade union. Human rights groups said Li was framed and tortured.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “Western experts say if Chinese leaders were to allow independent unions, that could help defuse labor discontent.”Early drafts of the Labor Contract Law of 2008 had clauses that would have allowed for more independent unions, but those were excised from the final version.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, June 20, 2010]

Mary E. Gallagher, a political scientist at the University of Michigan who studies Chinese labor, told the New York Times. “The final version also left out an earlier clause that said companies had to get union approval on major workplace changes.I would doubt very much that the Chinese Communist Party thinks that the benefits of an independent Chinese trade union outweighs the costs or outweighs the risks.”

Workers at a Honda parts factory in Zhongshan in 2010 made the formation of an independent union one of their main demands, along with wage increases.

The Hong Kong University student organization’students and Scholars against Corporate Misbehavior (SACOM) — reported on abuses of workers at Nine Dragons Papers, owned by Zhang Yin, a businesswoman regarded as one of the richest people in China. Founded in 2005 as a non-profit organization originating “from a students' movement devoted to improving the labor conditions of cleaning workers and security guards under the outsourcing policy — SACOM has a number of projects and reports on labor abuses at such companies as Disneyland Hong Kong, Giordano, Motorola and Wal-mart.

China's Trade Union Takes up a New Cause — Workers

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “China’s only legal trade union organization, a tool of Communist Party control long scorned by workers as a shill for big business, is experimenting with a novel idea: speaking up for labor. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post , April 28 2011]

“We have to win back the trust of workers,” Kong Xianghong, a senior trade union official, told the Washington Post. “Only if we truly represent workers will the workers not reject us.” Kong is deputy director of the Guangdong province branch of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions.

Since a strike at a Honda plant in Foshan near Guangzhou in southern China, Kong has been trying to convince workers that unlike their restive brethren in Poland before the collapse of communism or in Egypt before the fall of President Hosni Mubarak, they can rely on a labor organization beholden to the ruling party to champion their rights. “We realized the danger of our union being divorced from the masses,” said Kong, a veteran Communist Party member.

Lobbying on behalf of workers marks a departure for a labor organization that, though nominally committed to socialism, has generally focused on keeping workers in line and ensuring that the main motor of China’s economic rise — a steady supply of cheap, docile labor — keeps turning.

China’s system is rigidly intolerant of political dissent but often supple and responsive on economic matters. The party hasn’t softened its view that workers, along with all others, must never disrupt “stability.” ....The very success of China’s economic model has meant that workers, particularly migrants from once-impoverished inland regions, now have far more choice over where they work and for how much. This new generation, Kong said, is “not afraid” to make demands.

Han Dongfang, a Chinese labor activist who went to jail after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 for setting up a now-disbanded independent trade union in Beijing, says leaders of the official labor organization, at least in prosperous coastal areas, “now understand that they have to try their best to work in the direction of representing workers.”

Chinese Governments Do More To Help Workers

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “The official labor organization’s willingness to speak up for workers has been accompanied by a broader push by authorities in Guangdong, an incubator for many of China’s boldest reforms, to curb the raw exploitation that marred, but also fueled, the country’s initial economic takeoff. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post , April 28 2011]

The Guangdong provincial government, worried about labor shortages as migrants find work closer to home, raised the minimum wage in cities such as Foshan by nearly 20 percent. This covers all companies, not just foreign-owned multinationals. Authorities also calculate that paying more attention to the interests of labor will deter workers from taking matters into their own hands, as they did in Foshan at the Honda facility. The two migrant workers who organized the strike shunned the official union.

Mary Gallagher, an expert on Chinese labor at the University of Michigan, described China’s strategy as “helping workers so as not to empower workers.” Higher wages and better conditions aim to ensure that “they won’t ask for independent unions.” The Communist Party, she added, came to power in 1949 in part through its ability to mobilize labor, so it “is well aware of the threat” posed by labor activism it doesn’t control. Turmoil in the Middle East, where corrupt, state-controlled trade unions lost control of workers, has served as another reminder of how dangerous ignoring labor grievances can be. China, Kong said, “cannot be compared to Egypt.” But he added that “we need to absorb the lessons” of uprisings in Arab nations.

Local Governments Put Pressure on Companies to Set Up Trade Unions

In September 2011, the Japanese newspaper the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The Beijing municipal government is planning to pressure companies in the city into setting up labor unions by penalizing those that do not. The municipal government's tax bureau plans to impose a charge on companies that do not have labor unions. The charge would be equivalent to the total union contributions that a company would have to pay if a union did exist. [Source: Yasushi Kouchi, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 15, 2011]

The aim of the policy is understood to be reducing the gap between the rich and the poor, as the widespread establishment of unions is expected to result in the minimum wage being lifted. Implementing the policy would also result in a new additional expense for foreign companies that do business in China.

Some municipal governments in China, including Dalian in Liaoning Province and Nanjing in Jiangsu Province, have already implemented such a measure. Introducing the system in Beijing would likely see it adopted in other cities. According to a statement from the Beijing municipal government's tax bureau and the city's equivalent of a labor union federation, companies that have no labor union will be charged "2 percent of total labor costs"--the same amount companies are required to pay in labor union contributions.

Money collected from companies through the system is to be directed into a reserve fund.If a company establishes a labor union within three years, 60 percent of the money it has paid in charges will be given to the labor union. The remainder of the reserve fund will likely be paid to a labor union umbrella organization.

Labor Reforms in China

In a major speech marking the opening of National People’s Congress in March 2010, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao promised to extend worker’s compensation coverage to all those injured in the line of work.

In 2006, Walt Disney Japan told a Chinese firm that made character goods to stop fining plant employees for violating work rules. The Chinese company refused to comply and closed the plants and sued Walt Disney Japan for ¥70 million.

Some scholars and government advisers have advocated adopted Western-style collective bargaining.

Dongfang believes the answer to China’s labor problems is setting up functioning unions that can open a dialogue with management and address grievances and avoid problems by nipping them at the bud. He says there are even some Communist party officials, such as the party boss in Guangdong Province, who agree with him. Equally important, he said, is for governments to provide education, health services and other social benefits for migrant workers who are excluded from basic government benefits by resident laws. Dongfang then goes a step further, arguing local governments should set up special housing and other services for migrants because they have generated so much tax revenues for the governments.

Yet Beijing still shies away from allowing workers to choose representatives to negotiate salaries and other benefits with employers.

Labor Disputes and Arbitration in China

The leap in worker consciousness is best reflected in the rising number of labor disputes that have gone to arbitration or to the courts. In 2008, the year factory shutdowns surged, nearly 700,000 labor disputes went to arbitration, almost double the number in 2007, according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Last year’s numbers were roughly the same as those in 2008. If arbitration proves unsatisfactory, Chinese workers or employers can appeal to civil courts. In 2008, the number of labor cases in courts was 280,000, a 94 percent increase over the previous year, according to the Supreme People’s Court. In the first half of 2009, there were 170,000 such cases.

In many parts of China, there is now a backlog of labor disputes awaiting resolution. Some workers have had to wait up to a year for arbitration committees to address their complaints.

Moreover, government officials, perhaps to protect local employers, have pushed for disputes to be solved through mediation rather than reach the level of arbitration committees or courts, and they have not enforced labor laws strictly, especially in the aftermath of the mass factory closings, legal experts said. In late 2008, officials in Guangdong Province, where labor disputes are common, issued a report saying that 500 or so unofficial lawyers who represented workers were a source of growing trouble.

Lawsuits by Workers in China

Workers are also increasingly attempting to get help from the courts. The number of labor disputes accepted by labor arbitration committees n China rose from 4,000 in 1987 to 135,000 in 2000. The number of lawsuits rose from 17,000 in 1992 to half a million in 2000.

In a typical case, workers want the return of pension fund money that their employers have deducted from their pay but not placed in their pension funds. After months in court, delays, broken promises, protests and disruptions, the workers get $5000 each from their employers..

See Factory Injuries Under Dangerous Chinese Factories

Image Sources: China Labor Watch

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2011