RUSSIA AND CHINA

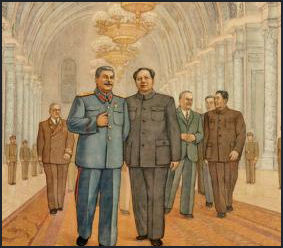

Mao and Stalin China and Russia share a 2,164 miles (3,483 kilometers) border. They have a history of mutual suspicion and hostility and remain suspicious of another despite their improved ties.

Russia and China have disagreed over the exact location of their common border since the 17th century. China once considered large chunks of Siberia and the Russian Far East as part of its territory. Russians began settling permanently in the Amur region in the mid-1850s. A treaty with the Chinese emperor gave them the north bank of the Amur River. At the time, the Chinese said the agreement was temporary. Chinese and Koreans living in the area were used as cheap labor to build the Trans Siberian Railroad..

After the Boxer Rebellion, in which a handful of Russians were attacked by Chinese, the Cossacks took revenge by launching an ethnic cleansing campaign on the Russian side of the Amur. Chinese men, women and children were herded to the river and told to swim to China. Most of those who tried to swim drowned, froze to death or were swept away by the current. Those that refused to swim were massacred. It is believed that 5,000 Chinese were killed around the Russian town of Blagoveshchensk from July 4 to July 10, 1900.

Wen Liao, chairwoman of the Longford Advisors, wrote, “From China’s standpoint...the Soviet collapse was the greatest strategic gain imaginable. At a stroke, the empire that gobbled up Chinese territories for centuries vanished. The Soviet military threat...was eliminated. China’s new assertiveness suggests it will not allow Russia to forge a de facto Soviet reunion and thus undo the post-Cold War set.”

In the second half of the 20th century relations between Moscow and Beijing oscillated between excessive dependence (particularly China on Russia) and almost zero interactions. Over the past 30 years, China's diplomacy, particularly its relations with Russia, has become far more sophisticated, nuanced, measured and matured. To a large extent, China's foreign policy has gone back to its deeper philosophical underpinnings of “unity, harmony with or without uniformity” ( he er bu tong). This is also one of the psychological anchors for the Sino-Russian strategic partnership after the two extreme types of relationship of “honeymoon” (1950s) and “divorce” (1960s and 1970s) between Beijing and Moscow. [Source: Asia Times, Yu Bin September 6, 2008]

Soviet Influence in the 1950s

Stalin and Mao in 1949 After the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, China reorganized its science establishment along Soviet lines--a system that remained in force until the late 1970s, when China's leaders called for major reforms. The Soviet model is characterized by a bureaucratic rather than a professional principle of organization, the separation of research from production, the establishment of a set of specialized research institutes, and a high priority on applied science and technology, which includes military technology. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Under the Soviet bureaucratic model, leadership was in the hands of nonscientists, who assign research tasks in accordance with a centrally determined plan. The administrators, not the scientists, controlled recruitment and personnel mobility. The primary rewards were administratively controlled salary increases, bonuses, and prizes. Individual scientists, seen as skilled workers and as employees of their institutions, were expected to work as components of collective units. Information was controlled, was expected to flow only through authorized channels, and was often considered proprietary or secret. Scientific achievements was regarded as the result primarily of "external" factors such as the overall economic and political structure of the society, the sheer numbers of personnel, and adequate levels of funding.

“Soviet influence also was realized through large-scale personnel exchanges. During the 1950s China sent about 38,000 people to the Soviet Union for training and study. Most of these (28,000) were technicians from key industries, but the total cohort included 7,500 students and 2,500 college and university teachers and postgraduate scientists. The Soviet Union dispatched some 11,000 scientific and technical aid personnel to China. An estimated 850 of these worked in the scientific research sector, about 1,000 in education and public health, and the rest in heavy industry.

“The Soviet aid program of the 1950s was intended to develop China's economy and to organize it along Soviet lines. As part of its First Five-Year Plan (1953-57), China was the recipient of the most comprehensive technology transfer in modern industrial history. The Soviet Union provided aid for 156 major industrial projects concentrated in mining, power generation, and heavy industry. Following the Soviet model of economic development, these were large-scale, capital-intensive projects. By the late 1950s, China had made substantial progress in such fields as electric power, steel production, basic chemicals, and machine tools, as well as in production of military equipment such as artillery, tanks, and jet aircraft. The purpose of the program was to increase China's production of such basic commodities as coal and steel and to teach Chinese workers to operate imported or duplicated Soviet factories. These goals were met and, as a side effect, Soviet standards for materials, engineering practice, and factory management were adopted. In a move whose full costs would not become apparent for twenty-five years, Chinese industry also adopted the Soviet separation of research from production.

Tensions Between Soviet Union and Maoist China

Russian and Chinese engineers

Despite common ideological roots and considerable Soviet assistance in over several decades, relations between China and the Soviet Union began to sour in the 1950s and got so tense that for a while China considered the Soviet Union to be its No. 1 enemy, presenting more of a threat than the United States.The relationship between China and the Soviet Union were strained by cultural differences between the two countries, personal difference between their leaders and ideological difference over the ways Communism was interpreted and implemented.

When Mao visited Moscow in 1949, it was several days before Soviet leader Joseph Stalin even acknowledged his presence. For his part Mao ignored the Russian food and ate meals alone in his room cooked by the Hunanese chef he brought with him from China. On visit to Russia in 1957 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, Mao became bored almost immediately at a performance of Swan Lake by the Bolshoi Ballet and asked Khrushchev, "Why don't they just dance normally?" He left after the second act. [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

Tensions in relations between the two countries had began to escalate in the mid-1950s. China was angry with the Soviets for failing to fulfill their promise to help China build a nuclear bomb and for siding with India during its border dispute with China. The urban-based Soviets and the rural-oriented Chinese had different concepts of what Communism was all about. Mao, a firm believer in world revolution, was also angered by the Soviet Union's relatively amicable relationship with the United States.

China and the Soviet split over ideological differences in the 1950s when with Khrushchev de-Stalinization speech, condemning personality-cult leadership, at a time when Mao was using a personality cult to push ahead the Great Leap Forward. In 1958, Mao Zedong welcomed Nikita Khrushchev in swimming trunks and invited the Soviet leader to join him for a swim even though he knew Khrushchev couldn't swim.

The Soviets withdrew their technical advisors from Chinese factories and weapons plants and demanded payment on loans. in 1960. A bridge over the Yangtze is a famous landmark in China because it was started with the help of the Russians, who pulled out when it was half done, believing the Chinese could never finish it, but the Chinese did.

Clashes Between Russia and China

Relations between China and the Soviet Union worsened when armed clashes broke out on the poorly defined border in the late 1960s. The 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and the buildup of Soviet forces in the Soviet Far East raised Chinese suspicions of Soviet intentions. Sharp border clashes between Soviet and Chinese troops occurred in 1969, roughly a decade after relations between the two countries had begun to deteriorate and some four years after a buildup of Soviet forces along China's northern border had begun. Chinese and Russian soldiers fought along several sections of the border, resulting in hundreds of deaths.

Based partly on Manchu claims to the region, Mao said Russia had imposed unfair borders on China and Vladivostok and Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East belonged to China. In one disputed area, along the Amur River, Chinese soldiers taunted the enemy by dropping their pants and mooning the Soviet guards on the other side of the border.

Particularly heated border clashes occurred in the northeast along the Sino-Soviet border formed by the Heilong Jiang (Amur River) and the Wusuli Jiang (Ussuri River), on which China claimed the right to navigate. In 1969, Chinese and Soviet soldiers fought a bloody battle on Damansky Island in the Ussuri River in the Russian Far East. The fighting stopped short of all-out war but launched a massive military build up on both sides of the border and triggered a protest in Shanghai on March 3rd and 4th 1969, with 2.7 million demonstrators (a world record). In the 60s and 70s, the border between China nd the Soviet Union was tightly sealed. Border provocations occasionally recurred in later years--for example, in May 1978 when Soviet troops in boats and a helicopter intruded into Chinese territory--but major armed clashes were averted.

“In the late 1970s, China decried what it perceived as a Soviet attempt to encircle it as the military buildup continued in the Soviet Far East and the Soviet Union signed friendship treaties with Vietnam and Afghanistan. In April 1979 Beijing notified Moscow that the thirty-year Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance--under which the Soviets aided the PLA in its 1950s modernization--would not be renewed. China joined the boycott against the Moscow Olympics in 1980 and participated n the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, which the Soviet Union boycotted.

Relations Between China and the Soviet Union Improve But Still Tense in the 1980s

Negotiations on improving Sino-Soviet relations were begun in 1979, but China ended them when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan late that year. In 1982 China and the Soviet Union resumed negotiations on normalizing relations. Although agreements on trade, science and technology, and culture were signed, political ties remained frozen because of Chinese insistence that the Soviet Union remove the three obstacles to improved Sino-Soviet relations. Although Chinese leaders publicly professed not to be concerned, the Soviet base at Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam, Soviet provision of MiG-23 fighters to North Korea, and Soviet acquisition of overflight and port calling rights from North Korea intensified Chinese apprehension about the Soviet threat. Soviet Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail S. Gorbachev's 1986 offer to withdraw some troops from Afghanistan and the Mongolian People's Republic (Mongolia) were seen by Beijing as a cosmetic gesture that did not lessen the threat to China. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the mid-1980s the Soviet Union deployed about one-quarter to one-third of its military forces in its Far Eastern theater. In 1987 Soviet nuclear forces included approximately 171 SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles, which China found particularly threatening, and 85 nuclear-capable long-range Backfire bombers. Approximately 470,000 Soviet ground force troops in 53 divisions were stationed in the Sino-Soviet border region, including Mongolia. Although 65 percent of these ground force divisions were only at 20 percent of full combat strength, they were provided with improved equipment, including T-72 tanks, and were reinforced by 2,200 aircraft, including new generation aircraft such as the MiG-23/27 Flogger fighter. Chinese forces on the Sino-Soviet border were numerically superior--1.5 million troops in 68 divisions--but technologically inferior.

In the late 1980s, China viewed the Soviet Union as its principal military opponent. Simmering border disputes with Vietnam and India were perceived as lesser threats to security. Although the PLA units in the Shenyang and Beijing military regions were equipped with some of the PLA's most advanced weaponry, few Chinese divisions were mechanized. The Soviet Union held tactical and strategic nuclear superiority and exceeded China in terms of mobility, firepower, air power, and antiaircraft capability. Chinese leaders reportedly did not consider a Soviet attack to be imminent or even likely in the short term. They believed that if the Soviets did attack, it would be a limited strike against Chinese territory in north or northeast China, rather than a full-scale invasion.

Improved Relations Between Russia and China

Russian President Dmitry

Medvedev in China April 2011

China and Russia currently have what the call a “strategic partnership.” The two countries are trying to increase trade, boost their economies and are united in their determination to keep the United States from dominating world politics. China is the biggest foreign buyer of Russian arms. It also desperately wants Russian oil.

Relations improved in 1989 when Gorbachev visited Beijing, ironically right before the Tiananmen Square massacre. Yeltsin visited China in April, 1995 and received "what may be the warmest welcome ever accorded a Russian leader in China."

Chinese President Jiang Zemin and Yeltsin in signed a series of peaceful cooperation accords in 1994 in Moscow. In the agreement China and Russia promised to stop targeting nuclear weapons at each other. They also settled the dispute over a 34-mile section of the Sino-Russian border, where a skirmish in 1969 resulted in several hundred deaths. In November 1997, Yeltsin and Jiang Zemin signed an agreement on border and joint water use.

On July 2001, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Jiang Zemin signed a 20-year friendship treaty and made the two countries official strategic partners In December 2004, Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jibao visited Moscow. Chinese President Hu Jintao and Putin met in Moscow in March 2007 and affirmed their strategic ties and addressed an audience with a image of a China panda hold hands with a Russian bear. It was Hu’s third visit to Russia. He called Putin “my close friend” and spoke of a “warm atmosphere of trust.” The two leaders discussed Iran and North Korea and promised to strengthen economic ties and cooperate to advance a “multipolar world” — an apparent rebuff to Washington’s global dominance

In July 2008, China and Russia signed a pact that finally settled the demarcation line of their 4,400-kilometer border and have cut troop levels along the Sino-Russian border. China has purchased billions for dollars of weapons while Russia has quietly given Bolshoi Ussurisky Island back — a 130 square mile (335 square kilometer) island is located in the Amur River near Khabarovsk — back to China. Some speculated the move might be a preview to a transfer of the Kuriles to Japan. Russian nationalists are not happy about these moves..

One of Dmitry Medvedev’s first moves as the new Russian president in 2008 was visit China.

See Minorities

China Gaining the Upper Hand in Its Relationship with Russia

In October 2011, Reuters reported, “China is gaining the upper hand in its much vaunted friendship with Russia due to Beijing's shift away from relying on Moscow for advanced weapons and deep problems with energy cooperation, a report released on Monday said. While leaders of both countries play up the extent of their alliance and strategic ties, this partnership is unlikely to develop into anything more significant, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) said. [Source: Reuters, October 2, 2011]

"In the coming years, while relations will remain close at the diplomatic level, the two cornerstones of the partnership over the past two decades -- military and energy cooperation -- are crumbling," the think-tank wrote. "As a result, Russia's significance to China will continue to diminish."

While both work closely at the United Nations and frequently oppose U.S. policies or Western demands for sanctions on countries like Syria, China and Russia also value their relationship with Washington, the report said. "Furthermore, there are strategic planners in Beijing and Moscow who view the other side as the ultimate strategic threat in the long term."

China once relied significantly on Russia for weapons. But dramatic advances over the past few years mean that China will actually become a competitor to Russia on the world stage. That is one reason why Russia does not wanted to export its most high-tech equipment to China, the report said. "A more advanced Chinese defense industry is increasingly able to meet the needs of the PLA (People's Liberation Army), limiting the need for imports of large weapon platforms," it said. "At the same time, it is unclear if Russia is able and willing to meet Chinese demands because of problems with its own arms industry and concerns that China will copy technology and compete with Russia on the world market."

In energy cooperation, ties have frayed, as the sides argue about details of oil and gas imports into China and as Beijing turns to other suppliers, notably in central Asia, SIPRI said. A $1 trillion deal to supply Russian gas to China over 30 years, supposed to be the high point of President Hu Jintao's visit to Russia in June, has failed to materialize. Sources close to talks said price differences between the world's largest energy producer and Beijing were still too big.

"China is now in a position to have greater expectations of and place demands on Russia, while Russia is struggling to come to terms with this new power dynamic," the report said. "In both countries, strategic planners warn that the present competition could escalate to a more pointed rivalry, entirely undermining the notion of a strategic partnership. "Consequently, China and Russia will continue to be pragmatic partners of convenience, but not partners based on deeper shared world views and strategic interests."

Trade, Resources and Energy and Russia and China

Trade between Russia and China was around $33.4 billion in 2006, just 2 percent of China’s total trade. While parts of Russia are flooded with Chinese goods, about all that Russia sells to China are military hardware and natural resources. Much of it is Russian oil which arrived in tank cars by train on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The cars carry 15 million tons of oil in 2006 and 10 million in 2005.

China is beginning to place great importance on its relationship with Russia as is becomes major supplier of China’s energy and one that is right at its doorstep.

In September 2010, China and Russia signed a series of energy and security deals and promised to boost their strategic partnership. The agreements covered a range of topics such as terrorism, nuclear energy, coal, aluminum, and banking. During th meeting Russian President Dmitry Mevedev and Chinese President Hu Jintao marked the 65th anniversary of the end of World War II and announced the completion of a Russia-China oil pipeline.

See Energy

Military Relations Between Russia and China

Moscow is anxious to earn money by selling arms and China is anxious to modernize and build up its armed forces. China buys about $1 billion worth of military stuff from Russia each year. It is the biggest foreign buyer of Russian arms and Russia is China’s main weapons supplier.

Russia has sold China with sent Sovremenny-class destroyers, SU-27 fighters, advanced MiG fighters, AWACS radar plane, cruise missiles, submarines, and heavy weaponry. It has also supplied China with pilots and trainers and has sent weapons designers and experts to help China with its cruise missile and nuclear weapon’s programs

Russia and China have been cooperating in military matters and sharing foreign intelligence since the early 1990s. In August 2005, Russia and China held joint military exercises called “Peace Mission 2005,” involving submarines, warships, helicopters, war planes, thousands of troops and some of the Russia’s most advanced technology.

The Exercises were held near Vladivostok in the Russian Far East and on the Yellow Sea near Shandong in China. In one live fire drill, 1,800 Russian and 7,000 Chinese troops launched a mock assault of the beaches of northern China while top generals from both countries sat at a desk together and watched. The exercises also included a simulated naval blockades, which included the firing of missiles and rockets while military music blasted from shipboard speakers.

China and Russia said the military exercise were part of their preparations to fight terrorists and insurgencies and “didn’t threaten any country.” Some analysts saw them as a demonstration to the United States that it was not a unilateral global power and a warning to Taiwan and Japan not to overstep their bounds. Others saw them primarily as a chance for Russia to show off its latest weapons to it best customer.

Russian and Chinese forces held another joint military exercises together in August 2007 in the southern Urals at Chebarkul testing Range. The maneuver involved about 6,000 troops from Russia, China and four Central Asian countries.

CHINA, RUSSIA, OIL AND NATURAL GAS

China is the world’s largest energy consumer and Russia is the world’s biggest energy producer. In recent years the two countries have struck a number of deals that take advantage of this relationship and the fact they border each other. During a visit by Russian Prime Minister Vladamir Putin to Beijing in 2009, China and Russia signed $3.5 billion in agreements that included setting a framework for two natural gas pipelines that will supply gas from fields in Russia’s Far East to China that will provide natural gas supplies almost matching China’s current consumption.As of 2006, Russia only supplied China with 2 percent of oil and 8 percent of its energy needs but that figure is expected to rise to around 15 percent of energy needs when planned pipelines are built. China doesn’t want to become too dependent on Russia for oil. There are still hostilities which date back to skirmishes on the 1960s.

China and Russia are also cooperating on energy deals in third countries in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America.

China and Russian Energy

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: China desperately needs what Russia has in abundance — oil, natural gas, coal, mighty rivers for hydropower, and nuclear know-how. And Russia, seeking to position itself as an “energy superpower,” has increasingly looked to China to help boost its economic and political clout. Between 2000 and 2010, China nearly doubled its consumption of oil, and it is on track to overtake the United States as the biggest petroleum importer by the end of the decade. [Source: Andrew Higgins, December 28, 2011]

To feed this demand, and their own bottom line, state-owned energy behemoths such as China National Petroleum Corp., or CNPC, have scrambled for supplies across the Middle East and Africa and closer to home in the disputed waters of the South China Sea. But perhaps no other country has offered quite as much promise — and frustration — as Russia, which produces more oil than even Saudi Arabia, sits just next door to China and, because of the retreat from democracy under Putin, is often on much the same wavelength as Beijing’s own authoritarian leaders.

Russia’s proven oil reserves are five times as big as those of China, which last year consumed three times as much petroleum as its northern neighbor. Russia also has the world’s biggest supplies of natural gas, a resource that until recently China largely neglected but that is now at the center of its energy policy. China plans to double gas use over the next five years and boost its role much further after that.”China looks very seductive,” said Vladimir Milov, a former deputy energy minister who took part in early negotiations with Beijing on oil and gas. But, he added, energy cooperation doesn’t depend on “just looking at the map. . . . There is a deep lack of trust behind the facade.” In the first 10 months of 2011, faraway Saudi Arabia sent 21 /2 times as much oil to China as Russia did, while Angola, even farther away, and Iran also supplied much more than Russia, according to Chinese trade statistics. Because of the new Siberian pipeline, Russia has nudged ahead of Oman for fourth place but still accounts for just 7 percent of its voracious neighbor’s total oil imports.

Russian Oil and Gas Companies and China

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: The energy sectors in Russia and China are dominated by giant state-owned corporations that pursue profit but are also entangled with security and other government agencies. The former head of CNPC, petroleum engineer Zhou Yongkang, sits on the Communist Party’s Politburo, combining a keen interest in energy with overall responsibility for China’s security agencies. [Source: Andrew Higgins, December 28, 2011]

Russia’s energy firms are studded with former KGB men. Tokarev, the head of Transneft, used to work at the KGB with Putin, according to Milov and Russian energy experts. Tokarev declined to comment on that assertion. Sechin, a former head of state oil company Rosneft, also began his career in what Russians call “the organs.” Tokarev believes that the firm grip of state companies on Russo-Chinese energy deals “makes things much easier” because private companies “have different criteria and different approaches to business.”

But it was a private Russian oil company, Yukos, that pioneered oil deliveries to China — by rail — and led an early push for a pipeline. Yukos’s China efforts fizzled after the 2003 arrest of its boss, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who — convicted of corruption and tax evasion — has since been in jail. In a written reply to questions, Khodorkovsky described the Chinese as “very tough negotiators but scrupulous partners.” In contrast, he said, Russian “state functionaries have demonstrated to China that internal ambitions and bickering are more important to the Russian bureaucracy than reliability in partnership.”

Khodorkovsky said that after he got thrown in jail China executed its contracts with Yukos “to the last possible moment” but then “pragmatism prevailed” and Beijing granted Rosneft, a Kremlin-backed Russian company, a $6 billion loan so that it could acquire Yukos’ prize assets and thus destroy Khodorkovsky’s oil business. With the pipeline project clouded by Khodorkovsky’s arrest and arguments over its route, Zhang Guobao, the then-head of China’s National Energy Administration, complained in 2006 that the project is “one step forward and two steps back.”

Russia- China Oil and Gas Pipelines

Much of Russia's oil supply to China comes on trains via the Trans Siberian Railway. Deliveries in 2006 were around 15 million tons, a 25 percent increase from the previous year.

Oil shipments from Russia via pipeline between Skovorodino in eastern Siberia and Daqing in northeastern China began in January 2011. The oil is delivered via a branch pipeline off the pipeline from Angarsk to Nakhodka. The costs of the branch was around $3 billion. The 1,000-kilometer part of pipeline from oil fields in eastern Siberia pipeline runs between Skovorodino in Russia and Danqing in China through Mohe on the China -Russian border on the Amur River. Russia and China have a 20 year contract with oil supplies beginning at around 15 million tons a year and increasing to 30 million tons a year. The first 704-kilometer section ending in Scovorodino on the Chinese border was built by the Russian pipeline monopoly Transneft, which was having trouble and was behind schedule on some parts of the pipeline because of lack of qualified workers.

When the entire $25 billion, 4,070-kilometer-long pipeline is finished it will be the world's longest. The main section runs in a 2,757-kilometer-long arc above Lake Baikal. Russian Prime Minister Putin said, “For China, this will help stabilize its energy supplies and security. For Russia, this offers a new market for exports to the Asia-Pacific region, especially dynamic and developing China."

Originally CNPC and the Russian oil company Yukos had plans to build a 1,400 mile pipeline to deliver crude from Angrask in eastern Siberia to refineries in Daqing. The oil was expected to begin flowing in 2003 and ultimately supply as much as a third of China's imports by 2030. The plan was given a major setback when Yukos president was jailed in June, 2003 and Japan provided Russia with lucrative financial incentives for an alterative pipeline through Siberia that bypassed China. The Japanese offered to provide $6 billion to cover construction costs and eventually provide billions more via private companies for oil exploration. This was much more than China was willing to offer.

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: Transneft eventually started work on a revised version of Yukos's pipeline plan after China came up with a $25 billion loan — and stipulated that the money be repaid with oil by Transneft and Rosneft. The line to China branched off a much longer pipeline that Transneft was building all the way to the Pacific coast to give Russia access to markets in Japan and elsewhere.: It is much shorter and cheaper and easier to build the pipeline proposed by Japan. Focusing on China alone, one Russian said, would be “economically risky” because it would make Russia dependent on a single customer. [Source: Andrew Higgins, December 28, 2011]

When Russia finished building its portion of the China oil pipeline in August 2010, Putin traveled to Skovorodino, near the Chinese border in eastern Siberia, for a celebration. “This project is important for our Chinese friends and for Russia," Putin said. He thanked Russian workers for their “really tremendous achievement” and remarked that China had yet to finish construction of its own — much longer — pipeline to the border with Russia. “Our Chinese friends need to do a little more work," Putin said.

Disputes between China and Russian Over Oil, Gas and Energy

In February 2009, China agreed to lend the Russian state oil company Rosneft and pipeline company Transneft $25 billion in return for supplies from huge new East Siberian oil fields. The loans will paid back in crude oil, 300,000 barrels a day, or 4 percent of China’s current demand, at a price of $20 a barrel, for 20 years at a time when the price of oil is projected to be between $60 and $70 a barrel. The deal allows Rosneft to pay off $8.5 billion in debt, much of it owed to foreign banks. The deal was mutually beneficial. China needs the oil and Rosneft needs cash as it has been having a hard time obtaining financing because of the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009. Some have called the deal the bargain of the century for China. The same month China made a similar deal worth $10 billion with Petrobras, the Brazilian state oil company.

While the law of supply and demand — as well as a common desire to curb the United States — pushes the two countries together, a long history of mutual distrust, similarly hard-nosed business styles and gnawing fear of dependency keeps them apart. “They look like the perfect partners, but this is a marriage made in hell,” said a Western energy executive who has worked with both countries. Russia and China, he added, are “so afraid of being outdone” by each other that negotiations tend toward all-or-nothing combat. [Source: Andrew Higgins, December 28, 2011]

Russia’s Gazprom, the world’s biggest gas company, has spent a decade haggling with CNPC over a proposed gas pipeline and a mammoth supply deal worth up to $1 trillion. Not only has construction not begun, but the two sides can’t even agree within a thousand miles on where the pipeline would go. During one negotiating session in Beijing at the Great Hall of the People, Russia’s deputy prime minister and energy czar, Igor Sechin, voiced frustration at the slow pace and suggested that experts from both countries simply be ordered to settle outstanding issues within 48 hours. The leader of the Chinese delegation, according to a Russian who was present, laughed out loud.

Yang Cheng, a former Chinese diplomat in Moscow who is a scholar at Shanghai’s East China Normal University, said Russia and China keep talking past each other. When Moscow first pushed for greater energy cooperation at the start of the 1990s, China “still thought it could supply itself,” and when it later turned to Russia and sought to gain stakes in oil fields, Western companies already had the inside track. Yang said that he remains optimistic in the long run but that each side has to stop “talking about its own stand and neglecting the other.”

The economic imperatives for greater cooperation remain powerful and, predicted a report issued in November 2011 by the International Energy Agency, should ultimately prevail, with China’s share of Russia’s total earnings from fossil fuel exports forecast to rise from the current 2 percent to 20 percent in 2035. But economic logic has rarely run in a straight line between Beijing and Moscow.

Disputes between China and Russian Over the Price of Oil from the New Pipeline

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: At exactly 48 minutes past midnight on January 1, 2011 Russia did something it had never done before: It began pumping oil to China across a 2,600-mile border that once bristled with tanks, troops and nerve-shredding tension. The oil flowed from eastern Siberia through a newly completed pipeline, the first such link between the world’s largest petroleum producer and its biggest energy consumer — and a symbol of what the two giant neighbors hail as a perfect symmetry of interests. [Source: Andrew Higgins, December 28, 2011]

“We and the Chinese need each other,” said Nikolai Tokarev, the head of Transneft, a state company responsible for the Russian portion of the pipeline. “They need oil, and we need a market,” added the Russian, a longtime associate of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. When it came time to settle accounts for the first deliveries, however, Tokarev got an unpleasant surprise: China, Transneft says, underpaid by more than $100 million. “Naturally, this did not cause delight,” Tokarev said. “We were surprised because there is a contract and this contract has signatures. It should be respected.”

The dispute hasn’t shut down the pipeline, but it has put a spotlight on a curious malaise at the heart of a would-be energy axis between Moscow and Beijing. It took years for Russian oil to finally start flowing to China, with both countries trumpeted a new era of cooperation, but once the oil arrived in China the two countries promptly started feuding over who owed what. Each month since has brought more squabbles over payments, though Transneft says the Chinese are now paying much closer to the agreed price. CNPC, which receives the Russian oil, declined to comment. Doing business with Europe, Tokarev said, is “easier and simpler. . . . We must get used to the Chinese, just as we and the Europeans got used to each other over many years.”

Russia and China Fail to Seal Gas Deal in 2011

In June 2011, Ben Blanchard of Reuters wrote, “Russia failed to agree on a 30-year gas supply deal with China in time for signing on Friday because of differences over the price of a deal, which could be worth up to $1 trillion (619 billion pounds). Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and Chinese President Hu Jintao had hoped to sign the deal, which would help power Beijing's booming economy and allow Moscow to diversify exports away from Europe, at an investment forum in St Petersburg.” [Source: Ben Blanchard, Reuters, June 17, 2011]

Russian Energy Minister Sergei Shmatko was upbeat on the prospects for eventually reaching an agreement between Russian state-controlled gas export monopoly Gazprom and China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC). "There should be no rush. We had a good chance to sign a deal during President Hu Jintao's visit to Russia, but both sides must show flexibility," he told reporters. "We expect talks to continue." A source close to the talks said the two sides had not been able to close the gap on price terms, with the Chinese seeking a fixed price and the Russians pushing to uphold the oil market link that underpins Gazprom's existing export contracts.

The failure to get the deal over the line came after five years of talks between Russia, the world's largest energy producer, and China, the largest consumer. The deal would have foreseen Russia exporting up to 68 billion cubic metres of gas per year to China, compared to expected export volumes to Europe of more than 150 billion cubic metres this year. For Russia, the deal would offer Gazprom an alternative market, assuaging Prime Minister Vladimir Putin's concern of over-reliance on European customers.

But while Hu has made securing energy for the world's second-biggest economy a diplomatic priority, relations with Russia have not been smooth. Negotiations have long been stuck on the issue of price, with Gazprom saying it will not accept a lower effective price than it receives from its core European customers.Negotiators for CNPC have signalled that they will pay no more than $250 per thousand cubic metres, sources at Gazprom said on Wednesday. Russia's gas export monopoly is still targeting a price that will make deliveries to China as profitable as those to European clients, who Gazprom says will pay $500 per thousand cubic metres in the fourth quarter of this year.

Industry officials and analysts said that, given the wide differences on price, political will alone was insufficient to get the deal done, with Russia concerned that offering easy terms to China would undermine its market position in Europe. "The difference on price was huge," said Mikhail Slobodin, executive vice-president for gas at TNK-BP. "China is very pragmatic. It doesn't matter about the visit of the Chinese president -- it's a question of economics."

Under early terms agreed over five years by negotiators, Russia would deliver 30 bcm per year from fields on the Arctic Yamal peninsula, the same fields which supply Europe -- via pipeline through the Altai region to northern China.China would also like to contract an additional 38 bcm from yet untapped fields in East Siberia. The combined income over three decades, assuming a price of $500 per thousand cubic metres, would generate some $1 trillion.

Chinese-Russian Mega Gas Deal on Second Gas Supply Route

In November 2014. Rt.com reported: “President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping have signed a memorandum of understanding on the so-called “western” gas supplies route to China. The agreement paves the way for a contract that would make China the biggest consumer of Russian gas. Russia’s so-called “western” or "Altay" route would supply 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas a year to China. The new supply line comes in addition to the “eastern” route, through the “Power of Siberia” pipeline, which will annually deliver 38 bcm of gas to China. Work on that pipeline route has already begun after a $400 billion deal was clinched in May. [Source: rt.com, November 9, 2014]

“After we have launched supplies via the “western route,” the volume of gas deliveries to China can exceed the current volumes of export to Europe,” Gazprom CEO Aleksey Miller told reporters, commenting on the deal. “We have reached an understanding in principle concerning the opening of the western route,” Putin said. “We have already agreed on many technical and commercial aspects of this project, laying a good basis for reaching final arrangements.”

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/, Chinese government, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2015