JUSTICE SYSTEM IN CHINA

Punishment in the 1920s The goal of the justice system has traditionally been to protect the interests of the state not the individual and to keep the masses under control. There is no independent judiciary in China. The courts are regarded as weak and subordinate to the Communist Party and the National People's Congress. Chinese justice is not based on the idea of innocent until proven guilty. For the most part one is guilty until proven innocent. People charged with crimes are nearly always convicted and sentences are rarely overturned.

China has a constitution with laws that are not all that different from laws in Western countries. The only problem is that these laws have traditionally been ignored, interpreted in strange ways or not enforced. There is a saying in China: “Power is greater than the law, money is greater than the law and connections are greater than the law.”

Tons of new laws have been passed. Newspapers publicize them and give information about telephone helplines. In May 1996, the Chinese Parliament revised the Chinese criminal code providing defendants with greater access to counsel, curtailed pretrial detention, gave defense lawyers the chance to challenge prosecutors, and added the presumption of innocence. But so far these reforms have not found their way in practice to many local criminal courts. One new law allows plaintiffs, not just judges and prosecutors to present their own evidence in a civil case. In 2004 there was discussion of introducing reforms to reduce the ability of the police to send people to labor camps without a trial.

China’s criminal justice system is steeply tilted in favor of the police and prosecutors. The vast majority of cases turn on confessions by suspects who have no access to defense lawyers until long after interrogation, if ever. Defense lawyers are powerless to do much except argue for a lesser sentence. Convictions are all but assured. Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: “With a conviction rate of 98 percent, Chinese prosecutors almost never lose. In a bitter twist of fate, Gu Kalai, the lawyer wife of Bo Xilai that was famously convicted of murder in 2012, once expressed an unshakable faith in her nation’s legal system, Jacobs wrote. In a book she wrote after visiting the United States in 1998 and successfully representing a Chinese company in a civil trial, she ridiculed the American justice system as doddering and inept. “They can level charges against dogs and a court can even convict a husband of raping his wife,” she wrote. By contrast, China’s system was straightforward and judicious. “We don’t play with words and we adhere to the principle of “based on facts,” she wrote. “You will be arrested, sentenced and executed as long as we determine that you killed someone.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 9, 2012]

The Supreme People’ Court is the highest court in the land. Its judges are appointed by the National People’s Congress. Below the Supreme People’ Court are Local People’s Courts, comprised of higher, intermediate and local courts. There are also Special People’s Courts primarily for military, maritime and transportation matters. Courts have names like the Beijing No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court.

The legal system is based on civil laws derived from the Soviet legal code and civil legal principles. The legislature has the power to interpret statutes. The constitution is ambiguous on judicial review by the legislature. High courts sometimes hand out judgments not based on evidence but based on orders from Communist Party leaders.

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “The contours of the Chinese legal system, as rights lawyers here know well, tend to be fuzzy. Petitioners are often thrown into extralegal holding cells known as black jails; dissidents are frequently cooped up in their homes for months on end; and domestic security agents have a variety of means to keep troublemakers in line.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs New York Times June 23, 2011]

China only has extradition policies with 37 countries. Sometimes sentences for crimes carried out outside of China are much lighter than those imposed for crimes in China. In August 2011, a Shanghai court sentenced a Chinese man to the relatively light sentence of 15 years in prison for murdering a taxi driver in Auckland, New Zealand because he “expressed remorse.” The man, who admitted to the crime, was not convicted of murder but for the China crime whose best English translation is “intentional assault.”

JUSTICE AND CRIME IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: China Law Blog chinalawblog ; China.org, official Chinese government source on Constitution and Legal System china.org.cn ; China.org, on People’s Courts china.org.cn

History of Law in China

Legal knowledge poster

The notion that the law is an instrument of control and discipline has been around for centuries and was the norm in imperial China. Laws were often the whim of the emperor. In 221 B.C. Emperor Qin set down strict disciplinary codes, brutally persecuted critics of his regime and set up a nationwide network of informants. In the Mao era things were often not that much different. The law was often simply what Mao decreed and anyone who opposed it could be dealt with harshly. The legal system that Mao set up was not all that different from the one of Emperor Qin.

A Chinese book of autopsies, “Hsi Yuan Chi Lu”(“The Washing Away of Unjust Wrongs”) was published about A.D. 1247. Among other things it describes how to determine whether a person found in the water after a fire drowned or burned to death (fire victims have soot in their lungs but drowning victims can not necessarily be determined by water in their lungs).

The first known example of insects being used to finger a killer occurred in 13th century China. Authorities investigating a slashing death asked villagers to hold up their sickles and were able to figure out the killer because flies flew to the sickle which had been cleaned by still contained enough traces of blood to attract the flies.

The “shangfang”system — complaining to higher authorities about injustice in hopes that the authorities will mediate a fair settlement — was a cornerstone of the Imperial justice system. People with complaints and people who claimed they were victims of injustice drew together petitions and presented them to the government in hopes that a sympathetic official would embrace their cause. The process as one might expect was often arbitrary and unpredictable and likely produced more disappointments than righted wrond.

Qiao Shi was leader of the legal reform movement under Mao. Once the No. 3 man in the Communist Party he was purged after aggressively promoting legal reform. Many of the reforms he called for have since been enacted. In 1991, Deng Xiapoing announced a plan to train 150,000 new lawyers and develop a modern legal system.

History of the Chinese Legal System During the Imperial Era

Contemporary social control is rooted in the Confucian past. The teachings of Confucius have had an enduring effect on Chinese life and have provided the basis for the social order through much of the country's history. Confucians believed in the fundamental goodness of man and advocated rule by moral persuasion in accordance with the concept of li (propriety), a set of generally accepted social values or norms of behavior. Li was enforced by society rather than by courts. Education was considered the key ingredient for maintaining order, and codes of law were intended only to supplement li, not to replace it. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Confucians held that codified law was inadequate to provide meaningful guidance for the entire panorama of human activity, but they were not against using laws to control the most unruly elements in the society. The first criminal code was promulgated sometime between 455 and 395 B.C. There were also civil statutes, mostly concerned with land transactions. Legalism, a competing school of thought during the Warring States period (475-221 B.C.), maintained that man was by nature evil and had to be controlled by strict rules of law and uniform justice. Legalist philosophy had its greatest impact during the first imperial dynasty, the Qin (221-207 B.C.)..

“The Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) retained the basic legal system established under the Qin but modified some of the harsher aspects in line with the Confucian philosophy of social control based on ethical and moral persuasion. Most legal professionals were not lawyers but generalists trained in philosophy and literature. The local, classically trained, Confucian gentry played a crucial role as arbiters and handled all but the most serious local disputes.

“This basic legal philosophy remained in effect for most of the imperial era. The criminal code was not comprehensive and often not written down, which left magistrates great flexibility during trials. The accused had no rights and relied on the mercy of the court; defendants were tortured to obtain confessions and often served long jail terms while awaiting trial. A court appearance, at minimum, resulted in loss of face, and the people were reluctant and afraid to use the courts. Rulers did little to make the courts more appealing, for if they stressed rule by law, they weakened their own moral influence. In the final years of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), reform advocates in the government implemented certain aspects of the modernized Japanese legal system, itself originally based on German judicial precedents. These efforts were short-lived and largely ineffective.

History of the Chinese Legal System Under the Communists

Between the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957 and the legal reforms of 1979, the courts — viewed by the leftists as troublesome and unreliable — played only a small role in the judicial system. Most of their functions were handled by other party or government organs. In 1979, however, the National People's Congress began the process of restoring the judicial system. The world was able to see an early example of this reinstituted system in action in the showcase trial of the Gang of Four from November 1980 to January 1981. The trial, which was publicized to show that China had restored a legal system that made all citizens equal before the law, actually appeared to many foreign observers to be more a political than a legal exercise. Nevertheless, it was intended to show that China was committed to restoring a judicial system. [Source: Library of Congress]

“During the Cultural Revolution justice was swift, arbitrary and often carried out by revlutionary mobs (See Below). During the fall of 1977, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and militia began turning over the responsibility for public security to the civilian sector. Judicial and public security workers held meetings to seek ways "to strengthen the building of the legal forces . . . and socialist legal systems." A theoretical study group from the Supreme People's Court affirmed that the courts and the public security organs were solely responsible for maintaining public order, and they called on the people to accept the views of superior authorities. The government set out to reorganize completely all judicial procedures and establish codes of criminal law and judicial procedure as quickly as possible. Law schools were reopened, professors were rehired to staff them, and legal books and journals reappeared

The Ministry of Justice, abolished in 1959, was reestablished under the 1979 legal reforms to administer the newly restored judicial system. With the support of local judicial departments and bureaus, the ministry was charged with supervising personnel management, training, and funding for the courts and associated organizations and was given responsibility for overseeing legal research and exchanges with foreign judicial bodies. The 1980 Organic Law of the People's Courts (revised in 1983) and the 1982 State Constitution established four levels of courts in the general administrative structure.

“Books: “Law and Society in Traditional China”by Ch'u T'ung-tsu; “Law in Imperial China”by Derk Bodde and Clarence Morris; Law and Justice; Chinese Law Past and Present by Fu-shun Lin. Justice in Communist China by Shao-chuan Leng and The Criminal Process in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1963 by Jerome Alan Cohen are good sources on legal developments in the early years of the People's Republic, and Shao-chuan Leng and Hungdah Chiu's Criminal Justice in Post-Mao China is an indispensable source for Chinese legal developments in the 1980s. Other extremely useful articles providing information on the criminal justice and penal systems can be found in various issues of Faxue Yanjiu (Studies in Law), Beijing Review, China News Analysis, and Foreign Broadcast Information Service, Daily Report:China.

Chinese Legal System During the Cultural Revolution

The state constitution adopted in January 1975 during the Cultural Revolution drew its inspiration from Mao Zedong Thought. Equality before the law, a provision of the 1954 state constitution, was eliminated. Moreover, people no longer had the right to engage in scientific research or literary or artistic creation nor the freedom to change residences. Some new rights were added, including the freedom to propagate atheism and write big-character posters.

“Socialist legality" under the 1975 state constitution was characterized by instant, arbitrary arrest. Impromptu trials were conducted either by a police officer on the spot, by a revolutionary committee (the local government body established during the Cultural Revolution decade), or by a mob. Spur-of-the- moment circulars and party regulations continued to take the place of a code of criminal law or judicial procedure.

“For example, during demonstrations in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in early 1976, three demonstrators were seized by police and accused of being counterrevolutionaries in support of Deng Xiaoping. The three were "tried" by the "masses" during a two-hour "struggle meeting," a session where thousands of onlookers shouted their accusations. After this "trial," during which the accused were forbidden to offer a defense (even if they had wished to), the three were sentenced to an unspecified number of years in a labor camp. In contrast to the milder sentences of the 1957 period, sentencing under the state constitution of 1975 was severe. Death sentences were handed down frequently for "creating mass panic," burglary, rape, and looting.

Lack of Rule of Law in China

Legal knowledge poster

Traditionally, Chinese political philosophy emphasized an avoidance of conflict and maintenance of social harmony through deference to benevolent authority. Law and litigation were viewed as unnecessary in the view that the government and society were fundamentally moral. Disputes were something that was worked on the local level by respected elders. Even so sophisticated legal codes were developed and they have been augmented and influenced by Western legal codes in the past century and a half or so.

Laws are weak. Enforcement is minimal. Punishments are often light. People can often weasel their way out even serious crimes with bribes as long as they pay enough. Laws are often muddled by internal contradictions and broad or distorted interpretations. Disputes are often settled through connections rather than rule of law.

The “rule of law” has traditionally been subordinate to the rule of leaders and the codes of Confucianism and then Marxist-Leninism. It is not unusual for internal directives to be handed down to judges by the Communist Party ordering the judges not to take up certain cases. In recent years, as China has become more active in the global economy there has been more pressure for to abide by international rules and the rule of law. In the late 2000s the state firmed up its grip on the justice system when reformer Xiao Yang was replaced as president of the Supreme People’s Court by Wang Shengjun, a career policeman with no legal training.

Explaining the laws for bus drivers in Europe worked a guide told a tour group of which Evan Osnos of The New Yorker was a member: “In China, we think of bus drivers as superhumans who can work twenty-four hours straight, no matter how late we want them to drive. But in Europe, unless there’s weather or traffic, they’re only allowed to drive for twelve hours!” He explained that every driver carries a card that must be inserted into a slot in the dashboard; too many hours and the driver could be punished. “We might think you could just make a fake card or manipulate the records — no big deal,” Li said. “But, if you get caught, the fine starts at eighty-eight hundred euros, and they take away your license! That’s the way Europe is. On the surface, it appears to rely on everyone’s self-discipline, but behind it all there are strict laws.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, April 18, 2011]

See Private Property, Business Customs, Economics

“But while China was precocious in developing a modern state...and was far more advanced in state administration than the contemporaneous Roman Republic, Fukuyama wrote: “it lacked other critical political developments, rule of law and accountable government. Rule of Law means that there is a body of law that is superior to the current ruler, which constrains the ruler’s decision making. This never existed in China the way it did in ancient Israel, Greece, Rome or India, in part because Chinese law was never grounded n religion. Rather the law was whatever the emperor said it was, and there was no institutional body in China that could over come his decrees.”

”The consequence of a lack f rule of law was that China could experience extreme forms of tyranny. The first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, uprooted thousands of aristocratic families, confiscated their property, instituted extremely harsh punishments and reportedly buried alive 400 Confucian scholars, as well as burning their books.”

”Accountable government, or what we call democracy, developed around the world at a much later time tham either the state or rule of law. Accountability does not necessarily depend on popular elections. Rulers can be educated to have a sense of moral responsibility to the people they govern, in the absence of procedural checks on their power. This existed in China, and was in many ways the essence of Confucian ideology. But procedural accountability, by which either elites or ordinary citizens can constrain rulers, never existed in China. The historical reason for his in my view was the fact that from an early date, there were never strong institutionalized actors apart from the state, like a landed aristocracy, independent commercial cities, or a well-organized peasantry, that would have formed a counterweight to the state.”

Strong State and Lack of Rule of Law

”China’s contemporary institutional legacy is thus a strong, centralized state and relatively good government. In the best of times, the Chinese state feels morally constrained to do the right things for its population in a way that is hard to replicate in other parts of the world. Thus virtually all the worlds’ successful authoritarian modernizers, including South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam and modern China, itself, are all located in East Asia and have historically been under Chinese cultural influence. They have compiled impressive economic and social development records when compared to comparable governments in Latin American, Africa or the Middle East. But Chinese tradition has not included rule of law or democracy and as a result, there are no institutional checks to prevent Chinese government from descending into despotism, as occurred during the Maoist period.”

”Unaccountable Chinese-style architecture comes at a price. In traditional China, common people were subject t all sorts of injustices perpetrated by landlords, corrupt local officials, bandits and the like. When their land was taken by a corrupt official, they had no recourse other than to protest to the emperor, The emperor wanted his realm to well governed and would try to discipline corrupt or arbitrary officials. But unless the people petitioning him were powerful r had some means of access to the palace, they had little chance of achieving justice...In many ways things are not all that different in contemporary China.”

”A lack of constraint by either law or elections means accountability flows only in one direction, upwards towards the Communist Party and central government and not downwards toward the people. There is a whole range of problems in contemporary China regarding issues like corruption, environmental damage, property rights and the like that cannot be properly resolved by the existing political system.”

Chinese Versus Western Law

Legal knowledge poster

While the Romans and the Western cultures that followed put their trust in written laws, Confucius and his disciples and Eastern cultures that followed distrusted written laws and put their trust in people and innate human goodness. The Confusions developed a code of conduct that defined how human beings interacted. This code of conduct was the basis of civil society rather than a written set of laws.

Confucianism’s social code is based on morality rather than laws: Confucius said: “If you govern by regulations and keep them in order by punishment, the people will avoid trouble but have no sense of shame. If you govern them by moral influence, and keep them in order by a code of manners, they will have a sense of shame and will come to you of their own accord.”

The 20-century Chinese historian Hsiao Kung-chuan wrote that if the early Chinese emperors had been exposed to Roman law "the Chinese of necessity would have undergone an absolutely different course of development in the thousand or more years thereafter." Even today the concept of written laws and written contacts is fairly weak in China and Asia.

On written contracts and written laws, one Hong Kong businessman told the Independent, "In a truly Chinese environment you can plead your way out of the restrictions imposed by the law."

One Harvard-educated lawyer, who did business in China, told the New York Times, “As a lawyer here I did incredible U.S.-style contracts that covered everything. But I always told clients that’s not enough. You need to work on relationships.”

Gap Between the Rich and Poor in the Chinese Justice System

Will Clem wrote in the South China Morning Post, “Two Shanghai court cases in the news in June 2011 serve to highlight the remarkable contrast between the haves and the have-nots in mainland society. In the first case, the offender was given a one-year jail sentence, suspended for one year; in the second, the verdict was for three years but suspended for five. On paper, one sterner than the other, but assuming both perpetrators keep their noses clean, the end result is not so different. The non-violent offences that landed them in the dock, however, could scarcely be further removed. [Source: Will Clem, South China Morning Post June 25, 2011]

The lesser crime involved an unemployed man in his fifties who decided to use his house keys to take out his financial frustrations on more affluent neighbours' cars. He reportedly said he "hated rich people" and had been angry about the fact he "didn't live a wealthy life". The scratches he caused to the nine vehicles' paintwork amounted to 19,900 yuan (HK$23,955) in damage.

The second case, by contrast, involved just under one billion yuan in illegal loans. Yan Liyan - listed in 2006 as the mainland's 56th richest man - had faced charges of embezzlement and contract fraud worth 2.7 billion yuan, but prosecutors were unable to substantiate the details. Instead, he was convicted of aiding and abetting two executives at a securities firm to use his companies to channel 937 million yuan in illegal loans to cover their losses on the Hong Kong stock market.

Yan had been held in custody for two years ahead of the trial but it seems bizarre that he could be convicted of involvement in such large-scale corruption and leave the court effectively a free man. (The crooked executives, incidentally, were jailed for 13 and 12-1/2 years.) It would seem the punishment was lighter than even he had expected. When the sentence was announced, Yan smiled broadly and called out to his family: "We're going home together for dinner." The big question in all this is: where is the deterrent? And given the size of the temptation, substantial deterrent is needed.

Arrests in China

There are few protections against arbitrary arrests and imprisonment. "Custody and repatriation" is a practice used by police throughout China to put beggars, drunks, physically and mentally people and illegal immigrants behind bars. People are often imprisoned if the police want them in jail they can not produce an identity card. The party sometimes sets quotas for the number of suspects arrested for different crimes.

The acquittal rate for 6.2 million crimes committed between January 1998 and September 2006 was only 0.66 percent. If anything the situation is getting worse rather better. The acquittal for 760,694 crimes committed in the first 11 months of 2006 was 0.22 percent.

According to Chinese law pregnant women are exempt from arrest or fines. Some purposely engage in criminal activity.

Chinese police are notorious for flouting the rules and arresting people planning to give testimonies the authorities don’t want to hear. They routinely use torture to extract confessions although, under Chinese law, confessions obtained through torture are inadmissable in court.

Family visits are rarely allowed for suspects under criminal investigation until after they are formally charged. Chinese law allows police to impose residential surveillance for up to six months before requiring them to make a decision about how to proceed with a case, as opposed to 30 days under criminal detention.

In the mid 2000s, the Chinese government said that it would start taping police interrogations to prevent forced confessions and the use of torture to extract confessions. The move was made after a highly publicized case involving a man that was imprisoned for murdering his wife for 11 years and was released after his wife turned up alive. The man had been tortured to extract the confession. After he was released a declaration of innocense from his arresting officer was found written in blood on a tombstone. The officer hung himself.

See Arbitrary Detainment, Police, Human Rights

Chinese Court System

The State Constitution of 1982 and the Organic Law of the People's Courts that went into effect in 1980 provide for a four-level court system. At the highest level is the Supreme People's Court, the premier appellate forum of the land, which supervises the administration of justice by all subordinate "local" and "special" people's courts. Local people's courts — the courts of the first instance — handle criminal and civil cases. These people's courts make up the remaining three levels of the court system and consist of "higher people's courts" at the level of the provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities; "intermediate people's courts" at the level of prefectures, autonomous prefectures, and municipalities; and "basic people's courts" at the level of autonomous counties, towns, and municipal districts. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to the 1980 Organic Law of the People's Courts (revised in 1983) and the 1982 State Constitution there are four levels of courts in the general administrative structure. Judges are elected or appointed by people's congresses at the corresponding levels to serve a maximum of two five-year terms. The Supreme People's Court stands at the apex of the judicial structure. Located in Beijing, it has jurisdiction over all lower and special courts, for which it serves as the ultimate appellate court. It is directly responsible to the National People's Congress Standing Committee, which elects the court president

The Organic Law of the People's Courts requires that adjudication committees be established for courts at every level. The committees usually are made up of the president, vice presidents, chief judges, and associate chief judges of the court, who are appointed and removed by the standing committees of the people's congresses at the corresponding level. The adjudication committees are charged with reviewing major cases to find errors in determination of facts or application of law and to determine if a chief judge should withdraw from a case. If a case is submitted to the adjudication committee, the court is bound by its decision.

“China also has special military, railroad transport, water transport, and forestry courts. These courts hear cases of counterrevolutionary activity, plundering, bribery, sabotage, or indifference to duty that result in severe damage to military facilities, work units, or government property or threaten the safety of soldiers or workers. Military courts make up the largest group of special courts and try all treason and espionage cases. Although they are independent of civilian courts and directly subordinate to the Ministry of National Defense, military court decisions are reviewed by the Supreme People's Court.

Gang of Four Trial

Trials in China

There are no juries. Trials are presided over by three judges in uniforms with insignias with balanced-scales on them. Defendants are allowed defense attorneys. Prosecutors have traditionally won 99 percent of their cases and verdicts are usually foreordained. Arrests are often announced after the prosecution has enough evidence to convict.

“In almost all cases in China, defendants are quickly convicted and sentenced. Most trials are administered by a collegial bench made up of one to three judges and three to five assessors. Assessors, according to the State Constitution, are elected by local residents or people's congresses from among citizens over twenty-three years of age with political rights or are appointed by the court for their expertise. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Trials are conducted in an inquisitorial manner, in which both judges and assessors play an active part in the questioning of all witnesses. (This contrasts with the Western adversarial system, in which the judge is meant to be an impartial referee between two contending attorneys.) After the judge and assessors rule on a case, they pass sentence. An aggrieved party can appeal to the next higher court.

By law, defendants are entitled to a trial in lower and higher courts. Almost any case can be appealed or retried, even with no good legal justification to do so. Powerful groups often ignore court rulings and find ways to have them overturned through bribes or connections while the case is being appealed.

An entire trial can take two or three hours or even less than that. One human rights activist said he was given only 20 minutes to mount a defense and was cut off when his time was up while the prosecutor was allowed much more time to present his case and allowed to carry on when his allotted time was up.

Some crimes such as drug possession, membership in Falun Gong and prostitution are considered to minor to waste with trial time and punishment in the regular prison system. In many cases people arrested on these charges are sentenced for up to three years without trial on recommendations from police committees and sent to special slightly-less-harsh prisons. There is a great deal of abuse with this system. The police have power to imprison people for whatever they want.

Electric cattle prods are sometimes used on defendants in the courtroom. After activist Yang Chunlin was sentenced to five years in prison, his sister said, “When he left the courthouse we shouted at him that he must appeal. He said “No need.” and turned to say more, but the police prodded him with an electric stick...I saw sparks, and then he was placed into a police car and driven away.”

See Torture, Human Rights.

Judges in China

Chinese judges are poorly trained and poorly paid. Many have no university education or legal training (in Shanxi Province one judge had only an elementary school education). Instead most judges are political appointees or former officers in the People's Liberation Army. Many are retired military officers hired on the basis of their connections not their merits.

Many judges regard themselves as "soldiers of the state." They take orders from party-controlled trial committees and require approval from the state for promotions and salary increases, which means they can be manipulated by the government. Reformers want judges to be given more independence, freedom and power.

Many judges are party members appointed with the approval of local party leaders. They are often expected to uphold the interests of the party and local business people as if they were party officials. Judges are manipulated by corrupt officials and routinely take bribes. Both plaintiffs and defendants routinely entertain judges and provide them with "travel expenses."

Currently China is facing a shortage of judges because of higher standards demanded by a national exam for judges, because many trained and experienced judges are retiring or leaving for jobs in private industry, and because the courts have become so overloaded with corruption cases. In many poor regions and areas inhabited by ethnic minorities the judges are so few in number and so overworked that much of the work is handled by clerks who get the judge to sign off on their work.

Lawyers in China

The number of lawyers has increased dramatically over the past few decades. In 1979, there were two law schools and 2,000 lawyers in China. In 1997, there were 200 law schools and 100,000 lawyers. In 2009 there were 165,000 lawyers, a five-fold increase from 1990 but still about 50,000 fewer than you can find in state of California and small when compared to 850,000 lawyers in the United States, which has a forth of the population of China. The majority of Chinese lawyers work in business but more and more of them are representing the poor and people who have been taken advantage of.

Defense lawyers have their licenses subjected to annual renewal from authorities that often can arbitrarily fail to renew it. They also have to depend on the goodwill of police and persecutors to take even basic steps to defend their clients.

So called “barefoot lawyers” — farmers who have educated themselves about the law — offer their advise to other farmers to help them solve their legal disputes.

Lawyers are allowed to operate with more autonomy than judges but can face prosecution if they stir up public disorder or reveal information deemed sensitive or secret.

In Beijing, the Beijing Judicial Bureau is an administrative agency that has supervisory authority over law firms registered in the capital. It charges high fees and often interferes in the cases carried out by firms under its jurisdiction.

These days lawyers who are stopped by obstacles in the bureaucracy and legal system but have the law on their side take case to the Internet to drum up public pressure to coerce the government to take their activities seriously.

In 2006, rules known as “guiding opinions” were introduced that require Chinese lawyers to submit to government supervision when representing clients in politically sensitive cases. Addressed to the new breed of activist lawyers who have taken up social and environmental issues, the rules restrict lawyers from “stirring up” news media coverage and effectively take away the legal system as a way of fighting issues such as land confiscations, corruption, pollution and other issues deemed sensitive by the government.

Crimes and Counterrevolutionary Offenses

The Statute on Punishment for Counterrevolutionary Activity approved under the Common Program in 1951 listed a wide range of counterrevolutionary offenses, punishable in most cases by the death penalty or life imprisonment. In subsequent years, especially during the Cultural Revolution, any activity that the party or government at any level considered a challenge to its authority could be termed counterrevolutionary. The 1980 law narrowed the scope of counterrevolutionary activity considerably and defined it as "any act jeopardizing the People's Republic of China, aimed at overthrowing the political power of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the socialist state." Under this category it included such specific offenses as espionage, insurrection, conspiracy to overthrow the government, instigating a member of the armed forces to turn traitor, or carrying out sabotage directed against the government. [Source: Library of Congress]

“Other offenses, in the order listed in the 1980 law, were transgressions of public security, defined as any acts which endanger people or public property; illegal possession of arms and ammunition; offenses against the socialist economic order, including smuggling and speculation; offenses against both the personal rights and the democratic rights of citizens, which range from homicide, rape, and kidnapping to libel; and offenses of encroachment on property, including robbery, theft, embezzlement, and fraud. There were also offenses against the public order, including obstruction of official business; mob disturbances; manufacture, sale, or transport of illegal drugs or pornography; vandalizing or illegally exporting cultural relics; offenses against marriage and the family, which include interference with the freedom of marriage and abandoning or maltreating children or aged or infirm relatives; and malfeasance, which specifically relates to state functionaries and includes such offenses as accepting bribes, divulging state secrets, dereliction of duty, and maltreatment of persons under detention or surveillance. [Source: Library of Congress]

Criminal law makes special provisions for juvenile offenders. Offenders between fourteen and sixteen years of age are to be held criminally liable only if they commit homicide, robbery, arson, or "other offenses which gravely jeopardize public order," and offenders between fourteen and eighteen years of age "shall be given a lighter or mitigated penalty." In most cases juvenile offenders charged with minor infractions are dealt with by neighborhood committees or other administrative means. In serious cases juvenile offenders usually are sent to one of the numerous reformatories reopened in most cities under the Ministry of Education beginning in 1978.

Punishment in China

Justice is quick in China. A couple of heroin smugglers from Hong Kong caught in the Kumming province were executed within a week after they were arrested. Sometimes criminal are executed within hours after they are convicted.

Punishment is often meted out based on the consequences of a crime rather than the intention. In 2001, one woman was executed for selling explosives without a license in Hebei Province. She usually sold the explosive to a nearby quarry but once she made the mistake of selling explosives a man who used them to bomb four apartments buildings, killing 108 people, even though the man said he needed the explosives for a quarry. Most people caught selling explosives without a license are simply fined.

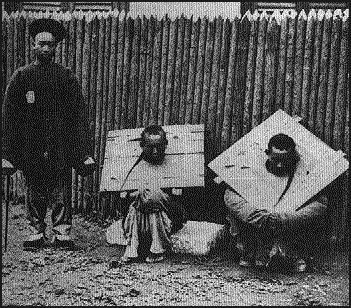

Medieval methods endured into the 20th century. In the 1920s, murderers in the Muli Kingdom were sentenced to five years in a dungeon where they were forced to wear a table-top-size neck board that prevented them from eating, grooming themselves, or lying down.

Prisoners are required to bow their heads to express remorse. Criminals found guilty of lesser crimes are sometimes loaded into trucks and taken to town squares where they are shamefully and humiliatingly displayed with signs around their necks. Small fines are given for littering and bike riding in off-limit zones.

In the spring of 2006, security guard named Xu Ting noticed that when he withdrew $140 from his account on an ATM only 14 cents was deducted. He them proceeded to make 170 withdrawals and pocketed $24,000, most of which was gambled away or lost in shady business deal. When the mistake was uncovered and Xu was unable to pay back the money charged with bank robbery and sentenced to life in prison. News of the case made it the Internet and outrage led to a retrial, a rarity in China.

Parade of prostitutes in Shenzhen

Criminal Sentences and the Death Penalty in China

Under the 1980 law, these offenses were punishable when criminal liability could be ascribed. Criminal liability was attributed to intentional offenses and those acts of negligence specifically provided for by the law. There were principal and supplementary penalties. Principal penalties were public surveillance, detention, fixed-term imprisonment, life imprisonment, and death. Supplementary penalties were fines, deprivation of political rights, and confiscation of property. Supplementary penalties could be imposed exclusive of principal penalties. Foreigners could be deported with or without other penalties. [Source: Library of Congress]

“China retained the death penalty in the 1980s for certain serious crimes. The 1980 law required that death sentences be approved by the Supreme People's Court. This requirement was temporarily modified in 1981 to allow the higher people's courts of provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities to approve death sentences for murder, robbery, rape, bomb-throwing, arson, and sabotage. In 1983 this modification was made permanent. The death sentence was not imposed on anyone under eighteen years of age at the time of the crime nor "on a woman found to be pregnant during the trial." Criminals sentenced to death could be granted a stay of execution for two years, during which they might demonstrate their repentance and reform. In this case the sentence could be reduced. Mao was credited with having originated this idea, which some observers found cruel although it obviated many executions.

Reform and Reeducation Through Labor

The overwhelming majority of prisoners were sentenced to hard labor. There were two categories of hard labor: the criminal penalty — "reform through labor" — imposed by the court and the administrative penalty — "reeducation through labor" — imposed outside the court system. The former could be any fixed number of years, while the latter lasted three or four years. In fact, those with either kind of sentence ended up at the same camps, which were usually state farms or mines but occasionally were factory prisons in the city. [Source: Library of Congress]

“The November 1979 supplementary regulations on "reeducation through labor" created labor training administration committees consisting of members of the local government, public security bureau, and labor department. The police, government, or a work unit could recommend that an individual be assigned to such reeducation, and, if the labor training administration committee agreed, hard labor was imposed without further due process. The police reportedly made heavy use of the procedure, especially with urban youths, and probably used it to move unemployed, youthful, potential troublemakers out of the cities.

“In the early 1980s, the people's procuratorates supervised the prisons, ensuring compliance with the law. Prisoners worked eight hours a day, six days a week, and had their food and clothing provided by the prison. They studied politics, law, state policies, and current events two hours daily, half of that in group discussion. They were forbidden to read anything not provided by the prison, to speak dialects not understood by the guards, or to keep cash, gold, jewelry, or other goods useful in an escape. Mail was censored, and generally only one visitor was allowed each month.

“Prisoners were told that their sentences could be reduced if they showed signs of repentance and rendered meritorious service. Any number of reductions could be earned totaling up to one-half the original sentence, but at least ten years of a life sentence had to be served. Probation or parole involved surveillance by the public security bureau or a grass-roots organization to which the convict periodically reported.

Image Sources: Posters: Landsberger; Gang of Four, Ohio State University; Prostitute parade, AP

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012