PETITIONS, PETITIONERS AND APPEALS OFFICES IN CHINA

Legal knowledge poster The only real legal recourse for complaints that ordinary people have is to file a petition through the network of petition and appeals offices that were originally set up in the Imperial era, when people were promised an audience with the Emperor, or a member of the imperial court or central bureaucracy if they had a problem. Now they are supposed to get an audience with a Communist Party cadre but that rarely happens.

The petition office in Beijing is officially known as the State Bureau for Letters and Calls.To file a petition applicants need to secure certain documents, draft the petition and collect signatures or chops or a thumb print from a certain number of people. The papers have to be prepared in a specific way and often need approval from various officials at various steps along the way.

The number of petitions visits grew from 4.8 million in 1995 to 12.7 million in 2005 — dwarfing the 4 million new civil cases heard by the courts that year. Few cases are ever resolved. Most end up in legal limbo.

The government says it receives 3 million to 4 million letters and visits from petitioners each year, but rights groups put the figure in the tens of millions. Some petitioners camp outside government for months, even years. Petitioners have filed complaints as diverse as illegal land seizures and unpaid wages. Former director-in-chief of the State Petition Handling Bureau, Zhou Zhanshun, has publicly admitted that more than 80 percent of petitioners raise genuine issues.

In 2004, 10 million petitions were filled but only 3 out 2,000 people who filed them had their problems resolved. Many petitioners had their cases referred back to officials the petitioners were accusing of wronging them. Petitioners who don’t get any response are told they should buy local officials gifts or take them out to dinner. Surveys done in the mid 2000s found that only 0.2 percent of petitioners receive any kind of response and only 0.02 percent of those who used the petition system said it worked.

In Beijing petitions are accepted in the People’s Supreme Court building, about one kilometer northwest of the Beijing South railway station. Many petitioners camp on a tract of land around the top court, known as the direct petition village, where rows of cheap tourist cabins have been set up.

Obstacles for Petitioners in China

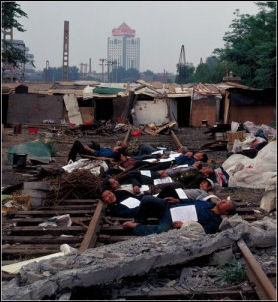

scene from the documentary film

“Petition”by Zhao Liang

The bureaucrats in the petition offices often employ delay tactics or try to extract bribes. If the petitioners successfully navigate the bureaucracy and submit their petition, they wait while it is reviewed. Sometimes it is reviewed by local officials; sometimes in Beijing. Often nobody looks at it.

Lawyers who have helped farmers fight for their rights within the legal system have been harassed and arrested. In February 2005, the government made it more difficult for peasants to file grievances with the government.

The area around the main petition office in Beijing is patrolled by thugs hired by local governments who round up petitioners to prevent complaints reaching the ears of the central government. Many are thrust into "black jails" and packed off home. A recently introduced system requiring people to submit their identity cards before buying a railway ticket has also been used to deter petitioners from travelling.

According to Human Rights Watch thousands of Chinese who have petitioned authorities for action on some grievance have been attacked, intimidated and detained. A survey by the group found that local government offices and courts not only routinely ignored the petitions but instead of investigating the grievances they put the petitioners in jail. A few have lost use of limbs due to torture. In Beijing, shanty towns occupied by petitioners have been burned to the ground. In Jilin Province, a woman was shackled, beaten and sentenced to a re-education camp for a year for trying to get compensation she was entitled to from factory, where her husband was injured.

“Paranoid” Petitioners and Bussing Petitioners in China

A couple of weeks before the 2008 Olympics began all the petitioners that could be found in Beijing were removed on buses. yesterday. A couple days before the busing a line of line 500 complainants from around the nation lined up outside the city’s petition office watched over by a half a dozen young policemen and a senior officer in a golf cart. After the busing the office was deserted.

In September 2009. a person identified as a long-time petitioner from southern Jiangxi province held up a French woman with a knife. Beijing police chief Ma Chenchuan told Hong Kong's Singtao Daily, Petitioners “have lost everything and are not afraid of death. When there is something big happening they think it is a good opportunity to make their appeals known by taking radical actions.” The central government has asked all provinces to “take back” their petitioners, said Ma, “but there must be thousands still at large in Beijing.”

In April 2009, Sun Dongdong, a professor of forensic psychiatry at Peking University, told China’s Newsweek: “I have no doubt that at least 99 percent of China's pigheaded, persistent 'professional petitioners' are mentally ill - they are all paranoid. If you investigate, you will find that the problems they are whining about have actually been solved already.” [Source: Stephanie Wang, Asia Times, May 9, 2009]

History of Petitioning in China

scene from the documentary film “Petition”

China’s petition system originated in the Ming Dynasty, from the 14th to the 17th centuries A.D., when commoners wronged by local officials sought the intervention of the imperial court. Two marble columns in front of the Tiananmen Gate to the Forbidden City served as ancient form of bulletin board from complainants who appealed to the Emperor for help.

The idea that wronged people could bring their complaints to higher authorities - all the way up to the emperor - dates back to the ancient history of the Middle Kingdom. The petition system, xinfang in Putonghua, was designed to keep local officials in check and deliver a message of justice to the emperor's subjects, thereby fortifying the emperor's power and authority. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, September 23, 2009]

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) initiated its own petition system in 1951, with more or less the same functions as the ancient institution. Its system provides a channel for grievances from localities, especially normal working folk, to be heard. This is crucial for such a huge country.

Since the Communist Party came to power, the right to petition the central government has been enshrined in the Constitution. In theory, the xinfang system can help reveal power abuse by local officials and help reverse unjust court decisions. Supervision from petition-handling departments, and particularly direct comments and instructions from some higher-ranking officials, can sometimes redress grievances and bring justice to petitioners.

Flaws within the Petition System in China

However, the system is inherently flawed. The petition-handling departments usually lack power and have to pass on most complaints to the relevant local authorities. When nepotism is rife and the relations between businessmen and civil servants are dubious, many petition letters, oral complaints and even personal petitions disappear. This explains why so many petitioners choose Beijing as their destination; they simply cannot expect the same local officials with whom they have grievances to provide them with justice. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, September 23, 2009]

The current petition system cannot effectively solve the problems of the petitioners. Rather, turns them into easy prey for retribution by corrupt local officials. Intercepting a large number of petitions has significant administration costs, and can be seen as a waste of public resources. Nevertheless, it has been reported that intercepting petitions is a priority for local governments' liaison offices in Beijing.

But how to address the inherent flaws in the system? Yu Jianrong, an expert on the petition issue at Chinese, suggested after an in-depth investigation on the petition system in late 2004 that the system should be closed altogether. His argument was compelling: the system simply does not work. Only three of the 2,000 cases he studied were solved, and then because they had caught the eye of certain powerful leaders and enlightened officials.

Retaliation and Violence Against Petitioners in China

Southern Metropolis Daily columnist Zhou Hucheng said, “Instances of petitioners being beaten, locked up in psychiatric facilities, or even sent to re-education through labor are too numerous to count.”

In 2001, Guo Guangyun, a minor official in Hebei province, revealed the activities of Chen Weigao, a provincial party secretary who later was convicted of corruption and removed. As a result, Guo was dismissed from his position, expelled from the CCP and imprisoned for two years. It was not until Chen's conviction that Guo was released. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, September 23, 2009]

In 1991, the 20-year-old son of peasant mother in Henan province died after a brutal beating by the local police and mine bosses. After local authorities dismissed her case, she cut off her son's head and carried it all the way to Beijing. In 2004, she was finally compensated with the lowly sum of 5,000 yuan. In China’s authoritarian state, senior officials tally petitions to get a rough sense of social order around the country. A successfully filed petition — however illusory the prospect of justice — is considered a black mark on the bureaucratic record of the local officials accused of wrongdoing. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

Southern Metropolis Daily columnist Zhou Hucheng blamed the pressure on local governments to maintain social stability, adding that in some places “even a single case of petitioning to higher authorities will result in officials from the petitioner's locality being penalised with a warning or removal from office ... So, for them, no method is too extreme in dealing with petitioners.”

For officials at all levels, it seems, the appearance of order — measured by reducing the number of petitions — is an acceptable approximation of actual order. The report in the state-run magazine Outlook said that there is heavy pressure for local officials to have “zero petitions” from their area, since their performance is linked to the number of grievances filed - a sign of instability - from their locality.

Reforms of the Petition System in China?

The Chinese government has admitted that the petitioning system needed to be improved. In a speech in March 2009, Premier Wen Jiabao said China should use its petition system to head off social unrest in the face of a worsening economy. “We should improve the mechanism to resolve social conflicts, and guide the public to express their requests and interests through legal channels,” he said.

In April 2009, in an apparent response to Wen speech, the People's Daily, published an editorial entitled “Intercepting Petitions Should Evolve Into Accepting Petitions”. The report also told the story of a veteran petitioner from a village in a southwestern province who, with his father, had petitioned the same cause from when he was a 17-year-old. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, September 23, 2009]

Each year for three decades he had aired his grievances on big occasions such as when national, provincial or municipal meetings were being held, but the government of his hometown always managed to intercept him. Each time he was intercepted the cost was at least 10,000 yuan. The author of the article lamented that the local officials preferred to spend on stopping people petitioning rather than patiently helping them to resolve real problems.

At around the same time the editorial was published, China's leadership ordered local officials to step up efforts to address public grievances in their areas amid a surge in complaints that have been brought to the central government. Local officials “should warmly receive the people, patiently listen to their appeals with compassion and responsibility, and make all efforts to solve their problems,” one of the directives stated.

Lu Yuegang, a journalist who writes about the plight of petitioners told the New York Times the petition system is flawed and that the government should abolish it and work on implementing the rule of law with judicial independence. “The petition system has almost zero effect,” he said in an interview. “Most petitions received by the state bureau are sent back to the local governments, the place where the cases originate. The system is not a problem-solving system but a receiving-and-forwarding system. And it just recycles the cases. This is the core problem.”

No More Petitioning in Beijing

In August 2009, the Communist Party’s Political and Legislative Affairs Committee posted a notice on its Web site saying: “Petitioners should not seek solutions by visiting Beijing; instead, they should seek redress locally, and if the case is rejected then central authorities may initiate a review.” Bringing cases directly to the capital, the notice implied, would be considered illegal. [Source: China Geeks, August 25, 2009]

“'No illegal petitioning is allowed, whether the cases are reasonable or not,” the notice said, adding that people who represent or instigate others to appeal will get 'criticism and education.'?

The report also promised that appeals would be dealt with one way or the other within sixty days, which at least prevents petitioners from waiting on edge for years as their petitions float endlessly in limbo (as happens sometimes under the current system). And there’s always the context to be considered. It’s possible this cutback on petitioning is just a temporary measure.

The new rules come as authorities are seeking to keep a lid on protests ahead of the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in October, 2009. One official from the legislative affairs committee said recently that an 'improvement' of the petitioning situation was needed to ensure “a harmonious and stable social environment for the celebratory events of the 60th anniversary of new China.”

Yang Dan, a petitioner from Honggang village in Hubei province appealing the seizure of her house for a government project, told the Wall Street Journal, said it is a good idea to solve the problem locally. “But the problem is that most local officials are corrupt,' Yang said. 'Who will supervise the local officials?'”

Film on Petitioning

Zhao Liang, an acclaimed Chinese independent filmmaker, made an investigative documentary called “Petition: The Court of the Complainants” (2010) about petitioners living on the fringes of China’s capital and their battles against a dysfunctional Chinese court system and their efforts to air their grievances against their local governments by traveling to Beijing where court cases demand much paperwork and they are made to wait for an indefinite period of time. The vast majority of petitioners are impoverished villagers from all over the country who travel far to the capital and typically end up waiting desperately in decrepit shantytowns for their cases to be settled. The film was special selection of the 2009 Cannes Film Festival.

In a review of the film, Joe Bendel wrote on his blog jbspins.blogspot.com, “They are the dregs of society. Scorned and maligned, they live a dangerous existence in crude shantytowns as they pursue their quixotic quest. They seek redress from the Chinese government and for filmmaker Zhao Liang, these “petitioners” are his country’s greatest heroes. The product of over ten years spent with these marginalized justice seekers, Zhao’s Petition stands as arguably the most damning documentary record of contemporary China to reach American theaters since the initial rise of the Digital Generation of independent filmmakers. [Source: Joe Bendel, jbspins.blogspot.com]

“Throughout Petition it is crystal clear the Chinese government has institutionalized corruption and hopelessly stacked the deck against the petitioners. Those victimized by unfair rulings have limited options locally for appeal (from the same corrupt bodies), so their only recourse is through the Kafkaesque “Petition Offices” in Beijing. Never in the film do we see the bureaucrats there actually give a petitioner satisfaction. They do keep records though. In fact, the local authorities have a vested interest in maintaining low petition numbers. Hence, the presence of “retrievers,” hired thugs who physically assault petitioners as they approach the petition office.

Petition is definitely produced in the fly-on-the-wall, naturalistic style of Jia Zhangke and his “d-generate” followers, but there is no shortage of visceral drama here. Each petitioner we meet has an even greater story of injustice to tell. Perversely, it seems it is those who do not take bribes who usually find themselves prosecuted in China. Petitioners are arrested, beaten, and even die under mysterious circumstances. Yet, it is through Zhao’s central figures, Qi and her daughter Juan, that we experience the emotional drain of the petitioning process with uncomfortable immediacy. Frankly, even if you have seen a number of Chinese documentaries, this film will still profoundly disturb you.

Zhao deserves credit for both his significant investment of time and his fearlessness. Not surprisingly, filming is strictly prohibited in the Petition Offices, but that did not stop him from trying, often getting more than a slight jostle for his trouble. Indeed, Petition represents truly independent filmmaking. Petition is the cinematic equivalent of a smoking gun. It is impossible to maintain any Pollyannaish illusions of about the rule of law in China after watching the film. Yet, like Zhao, viewers will be struck be the petitioners’ indomitable drive for justice. May God protect them, because their government certainly won’t. A legitimately bold and honest film that needs to be seen.

Wen Jiabao Shows Up at a Petition Office and Encourages Criticism

In January 2010, Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao surprised a lot of people when he appeared at the nation’s top petition bureau in Beijing, where ordinary people go to file grievances, and encouraged citizens to criticize the government and press their cases for justice, David Barboza wrote in the New York Times. “The move was unusual because the national petition bureau is known as a lightning rod for anger about official corruption, illegal land seizures, labor disputes and complaints of all sorts. [Source: David Barboza New York Times, January 26, 2011]

“We are the people’s government and our power is vested upon us by the people,” Wen said during the visit, according to state-run news media. “We should use the power in our hands to serve the interest of the people, helping them to tackle difficulties in a responsible way.” The state-run news media showed images of the prime minister meeting with a small group of petitioners at the bureau. The state-controlled media reports said he encouraged government workers to handle the petitioner cases properly.

“Mr. Wen also instructed officials to make it easier for citizens to criticize and monitor the government,” Barboza wrote. “State-run media said it was the first time a prime minister has appeared at the bureau to meet ordinary petitioners since the founding of the Communist state in 1949. In recent months, Mr. Wen has appeared to press for political reform, though analysts are uncertain about whether he is pushing on his own or with the support of a broader segment of the nation’s leadership.”

The media reports gave prominent display to articles about the visit in editions and blogs and Internet forums in China were buzzing with chatter about the visit. More than 6,000 postings about the visit appeared on the popular Web site, Netease.com, many of them praising the prime minister. But there was also some criticism. On Sina.com’s popular Chinese microblog, someone named Langzi wrote, “Shouldn’t Wen be more concerned about how laws and rules are enforced.” Another blogger added, “Chinese people are still dreaming that a lord will come and implement justice.”

Petitioners and Retrievers in China

Local officials don’t like it when their constituents try to petition the central government over some problem they have at home because it makes them look bad. Some hire bounty-hunter-like thugs known as “retrievers” to retrieve the petitioners before the have a chance to petition the government.

The retrievers stake out train stations, petition offices and cheap hotels and set up traps to catch them. When they are caught they are sometimes handcuffed, beaten up, tortured and locked into hotel rooms or even the trunks of cars and brought home.

When they are brought back to their hometown the petitioners are sometimes thrown in jail or a mental hospital. One victim of such tactics told the Los Angeles Times he was slapped around by police and diagnosed with a “mental disorder.” He had powerful drugs forced down his throats that he said caused him to have a heart attack. Another said he was tortured with chopstick shoved under his fingernails and a “tiger chair” that bent his knees into a position that nearly broke them.

The retrievers are paid well by Chinese standards. They typically earn a salary of $700 a month plus $250 for every petitioner they capture. One retriever that has done quite well said that his busy season was before major political meetings when he could catch up to 25 petitioners in a week. Some do well by bribing staff at the petitioner’s office not to look at cases.

Some retrievers dress like petitioners to blend in and find people by asking them where they from. Even when the person lies the retriever can tell where they are from by their accent. Some petitioners avoid capture by dressing like retrievers and jumping from moving vehicles when they are caught.

The financial rewards for apprehending petitioners can be irresistible. According to a directive obtained by Chinese Human Rights Defenders, the police in one Hunan Province county are authorized to pay nearly $300 for each petitioner who is detained. The money ends up in the pockets of the interceptors, corrupt petition clerks and those who run the black jails. The organization said that officers in one Beijing police precinct demanded as much as $140 for each petitioner they turned over to provincial interceptors. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

Being Retrieved in China

Wu Lijuan, a seasoned petitioner from Hubei Province, said she helped coordinate over 10,000 former bank employees who came to Beijing from across the nation last week. She said most of the petitioners, middle-aged women seeking more compensation for their dismissals, were rounded up outside the main petition office and put on buses. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

Those who escape the dragnets are often betrayed by employees at the very offices set up to process petitions. Sun Lixiu, 51, a farmer from Sichuan Province, said a clerk at the State Council petition office asked for her ID card, handed back an application form and then tipped off interceptors, who took her to a black jail, where she was held for a day. No one can be trusted, said Sun, who is seeking to free her husband from the local police station, where he has been held...after accusing town officials of embezzlement.

Police Mistakenly Beat Official's Wife Thought to Be Petioner

In July 2010, a 58-year-old woman thought to be a petitioners was beaten so severely for more than 15 minutes by plain clothes policemen outside a government office in Hubei Province she suffered a concussion and nerve damage, In turned out she was not a petitioner but the wife of senior civil servant who had gone to the office to meet her husband.

According to Southern Metropolis Daily said six unidentified men rushed out of the gate and began pummelling her. They were later identified as public security officers who had allegedly been assigned to “subdue” petitioners.According to the newspaper, she was then taken to a police bureau and scolded when she requested medical treatment. Only after she called her husband — who is reportedly in charge of maintaining stability, meaning he would oversee the handling of petitioners — was she taken to hospital, where staff said she had concussion and other injuries. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, July 22, 2010]

The incident resulted in Chinese netizens commentators demanding better treatment of petitioners and commenting on the response to the incident. . One person wrote: “Does it mean the police are not supposed to beat leaders' wives, but that the ordinary people can be battered?” Hu Xingdou, an economics professor at Beijing Institute of Technology and a well-known blogger on social affairs, said: “Cases like petitioners being beaten up are happening again and again; the only special thing about this one is that they beat the wrong person ... There wouldn't be news [about the case] if she was an ordinary person.”

Southern Metropolis Daily, columnist Zhou Hucheng said, “Instances of petitioners being beaten, locked up in psychiatric facilities, or even sent to re-education through labor are too numerous to count.”

Petitioner Sent to a Mental Hospital in China

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Local officials in Shandong Province have apparently found a cost-effective way to deal with gadflies, whistle-blowers and all manner of muckraking citizens who dare to challenge the authorities: dispatch them to the local psychiatric hospital. [Source: Andrew Jacobs New York Times, December 8, 2008]

“In an investigative report the state-owned newspaper Beijing Times, public security officials in the city of Xintai in Shandong Province were said to have been institutionalizing residents who persist in their personal campaigns to expose corruption or the unfair seizure of their property. Some people said they were committed for up to two years, and several of those interviewed said they were forcibly medicated. The article said most inmates were released after they agreed to give up their causes.”

“In an interview with the newspaper, the hospital’s director, Wu Yuzhu, acknowledged that some of the 18 patients brought there by the police in recent years were not deranged, but he said that he had no choice but to take them in. The hospital also had its misgivings, he said. Xintai officials do not see any shame in the tactic, and they boasted that hospitalizing people they characterized as troublemakers saved money that would have been spent chasing them to Beijing.”

The article in The Beijing News was also noteworthy in that it was even printed, considering the sensitivity of the topic it broached, and the high degree the story was picked up by other news outlets, including such Communist Party stalwarts as People’s Daily and the Xinhua news agency.

China's practice of treating troublemakers as psychiatric patients goes back to the Cultural Revolution, during which the profession of psychiatry was outlawed.

Another Petitioner Sent to a Mental Hospital in China

In October 2008, Sun Fawu, a farmer seeking compensation for land spoiled by a coal-mining operation in Shandong province, was captured by local officials as he tried to travel Beijing to present a petition and was detained at Xintai Mental Health Center for more than 20 days. He was released after he signed a waiver of petition. [Source: Andrew Jacobs New York Times, December 8, 2008]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “During a 20-day stay, Sun said, he was lashed to a bed, forced to take pills and given injections that made him numb and woozy. According to the paper, when he told the doctor he was a petitioner, not mentally ill, the doctor said: I don’t care if you’re sick or not. As long as you are sent by the township government, I’ll treat you as a mental patient.”

“In a telephone interview broadcast on Shandong provincial television, an unidentified municipal official suggested that those confined to the mental hospital had gone mad from their single-minded quest for justice. There are some people who have been petitioning for years and become mentally aggravated, the official said.”

Xu Lindong, a villager from central Henan who petitioned his local government over a land dispute, spent six years in psychiatric hospital, where he endured of interrogation, electric shocks and forced drugging. He was released in 2010 after the reform-minded China Youth Daily exposed his case. During his incarceration, Xu's family had no idea where he was. He is said to be physically broken bur is determined to seek justice by the government and the psychiatric hospitals that confined him. [Source: Asian Times, Kent Ewing, May 8, 2010; Mitch Moxley, July 9, 2010]

Zhou Rongyan, an office director for the Agricultural Committee in Chongqing, was sentenced to prison for 10 years in 1998 for fighting for petitioners' rights. A psychiatrist diagnosed her with a mental disorder, though the Chongqing Procuratorate later issued a statement to say she did not. On her release, Zhou started investigating mental illness in China and found that at least 1,000 had been detained illegally based on false psychiatric diagnoses, according to a post she placed on Tianya, a popular Internet forum.

Black Jails in China

In 2008, there was report that citizens in the city of Xintain on Shandong Province who tried to petition the government were locked up in mental hospitals to keep them from airing their complaints about local injustices. Some of the detainees were reportedly drugged.

Sometimes petitioners are thrown into “black jails,” illegal detention centers, to shut them up or keep them from filing their petitions. One 59-year-old woman, whose nephew was arrested, told the Los Angeles Times she was nabbed and placed in an isolated stockroom and held for days with about 100 others and finally released with her ailing husband and then abducted again and held for several weeks in a dilapidated private home. [Source: John Glionna, Los Angeles Times, January 2010]

Humans Rights Watch has released a 51-page report on he issue call “An Alleyway in Hell: China’s Abusive Black Jails”. It cites beatings, rapes, intimidation and extortion that have taken places at them. One victim was quote in the report as saying, at the place he was sent there were “locked steel doors ad windows. We never left our rooms to eat. We were given our meals through a small window space.”

Attention to the issue was raised in December 2009 when a guard at a black jail was sentenced to eight years in prison for raping a detained college student. Nicholas Bequelin, a senior Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, told the Los Angeles Times, “As China tries to build a functioning legal system, this gnawing black hole for human rights grows right there.”

The Communist Party initially denied the jail existed but then acknowledged them in an article in the Outlook, which is owned by the official New China News Agency, saying there were at least 73 black jails in the Beijing area alone and an estimated 10,000 people have been detained in hundred of jails at one time.

According to the Los Angeles Times and Human Rights Watch the jails reportedly came into existence a few years ago after the government abolished another system that allowed officials to jail petitioners they considered a threat. Under the for-profit system private jail operators receive $22 to $44 a day per person, creating an incentive to keep victims imprisoned for long period.

A petitioner who was held for four days in a shed attached to a run-down hotel before he escaped told the Los Angeles Times, “I was held in a small room with the door locked from the outside. There was a big iron gate that cut us off from the outside world. There were guards keeping an eye on us all the time. They didn’t beat us. But I was just given green peppers with rice every day for food.” When confronted by the press the owner of the hotel said he had no knowledge of black jails. “They are help centers to assists petitioners with no transportation to get back to their homes. They’re not jails,” he said.

Human Rights Watch has estimated that 10,000 people pass through the black jail system each year, with the number including some who pass through more than once. Some of those detained in black jails have been children.

Black Jail Operation

The Black Jails are in run-down hotels, nursing homes and even psychiatric hospitals. The ones in Beijing are often tucked away in rough areas of the city’s south side, amid dirty hotels and guarded by men in dark coats. Human rights workers say that an underground network of jails was first established in 2005 and were aggressively expanded in the months before the Olympics. According to the state-run magazine Outlook, Black Jails sprung up to provide food and accommodation, transportation and repatriation for the petitioners.

Local officials pay black jail operators 100 yuan ($15) to 300 yuan ($45) per day for each petitioner held captive to hold prisoners until they can be picked up and returned home. One security company manager surnamed Zhang was quoted in the Outlook report as saying that his company had been hired by seven or eight different provincial or city governments to provide such services.

The police in Beijing are regularly accused of turning a blind eye or even helping local thugs round up petitioners. That raises suspicions that the central government is not especially upset about efforts to undermine the integrity of the petition system. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

Rights advocates say that black houses have sprouted in recent years partly because top leaders have put more pressure on local leaders to reduce the number of petitioners reaching Beijing. Two of the largest holding pens, Majialou and Jiujingzhuang, can handle thousands of detainees who are funneled to the smaller detention centers, where cellphones and identification cards are confiscated.

Victims of Black Jails

The victims of Black Jail are mostly petitioners: ordinary Chinese who travel to Beijing and other provincial capitals seeking a resolution to grievances — including corruption, land grabs and abuse — that local officials have ignored. They are grabbed off the street, often by those very local government officials or their agents. Often, police either ignore or actively cooperate with the “retrievers.”

In March 20009, Wang Shixiang, a 48-year-old businessman from Heilongjong Province, came to Beijing to agitate for the prosecution of corrupt policemen. Instead, he was seized and confined to a dank room underneath the Juyuan Hotel with 40 other abducted petitioners. During his two days in captivity, Wang said, he was beaten and deprived of food, and then bundled onto an overnight train. Guards who were paid with government money, he said, made sure he arrived at his front door.[Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

One 52-year-old detainee from Liaoning Province told Human Rights Watch, “I was detained by retrievers from Liaoning who were in plain clothes and never showed me any identification, I doubt they had identification. They never told me the reason they detained me; they never even spoke to me and didn’t tell me how long they were going to detain me.”

Another said while in detention he was kneed in the chest and pounded in his stomach until he lost consciousness. “After it was over I was in pain, but they didn’t leave a mark on my body.”

A 21-year-old student, who traveled to Beijing to petition about being ridiculed by her teachers and classmates, was held with other citizens and raped by a security guard. About 70 petitioners later broke out and reported the incident to police.

Story of One Black Jail Victim

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “The story of Wu Bowen, 61, a retired shop clerk from Zhejiang Province, is typical. On Feb. 25 she came to the capital to file a petition seeking more compensation for the demolition of her home. The next day, as she sat on the curb, a policeman told her that as an out-of-towner, she had to register at the precinct. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, March 8, 2009]

“Once there, however, the officer called the Zhejiang Province liaison office in Beijing. Soon after, a clutch of interceptors led her to a hotel not far from the city’s main tourist attractions. After nine days of confinement, Wu stole back her cellphone and revealed the hotel’s address to her son, who called the offices of The New York Times.”

“When three men reluctantly opened the door to Room 208 at the Zhanle Hotel, Wu cried out for help. Confounded by the presence of foreign journalists, the men seemed unable to prevent Wu from escaping, although they begged her to stay, saying she could not leave until a local county official arrived with their reward money. Out on the street, Wu was shaken but undeterred. Asked if she wanted to be taken to the train station so she could return home, she shook her head. No, she said. I’m going to stay in Beijing until I get justice.”

Chinese Government Response to Black Jails

For a some time authorities denied such a system exists. During testimony to the United Nations Rights Council in February 2009, Song Hansong, a representative of China’s Supreme People’s Procurate, said, “There are no such things as black jails in our country.”

In November 2009, a muckraking-style article on the black jails surprisingly was run in the state-run Liaowang (Outlook) magazine, which is for the party elite. The article revealed a system of secret detention centers in Beijing where Chinese citizens are forcibly held and sometimes beaten to prevent them from lodging formal complaints with the central government. It called the extensive network of secret jails a “chain of gray industry” whose existence “damages the legitimate rights of petitioners and seriously damages the government's image.”

Because the government had long denied that “black jails” even existed the article was widely seen as an indication that the government was opening up and acknowledging problems it long covered up. A spokeswoman with Chinese Human Rights Defenders told AP, “The fact that they have acknowledged this means that other publications will be more open to discussing this topic. Just by publishing the article, it means we can talk about this issue, at least in a controlled manner. It's no longer a censored topic.” [Source: Tini Tra, Associated Press, November 25, 2009]

Ultimately, if the articles mark the beginning of more public disclosure about black jails, that could prod the government into action, said Phelim Kine, a researcher with Human Rights Watch, which recently released a 53-page report on the illegal detention centers.

Alarmed by their unchecked spread, a group of lawyers has taken to organizing citizen raids that seek to free detainees through a show of force. One of the lawyers involved in this is Xu Zhiyong.

Image Sources: 1) Chinese Posters, 2) deGenerate films; 3) YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012