PRISON AND LABOR CAMPS IN CHINA

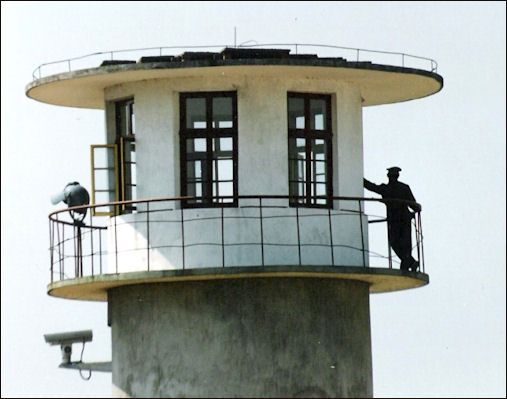

Outside Chengdu prison China has the largest prison population in the world. It has 670 prison with around 1.5 million prisoners, including 19,000 juveniles. According to the Chinese Ministry of Justice there are 1.3 million prisoners in prison, which are often referred to as “reform through labor” camps. Another 260,000 are in slightly less harsh “reeducation through labor” prisons. These are regarded as labor camps.

Since the establishment of the Chinese republic in 1949, criminals, political and religious dissidents and people deemed enemies of the state have been sent to labor camps. By one count 400,000 people have been sent 310 camps. According to another estimate 2 million to 6 million inmates have been sent to 1,250 to 5,000 facilities.

People are still sent to re-education centers where they undergo brainwashing study sessions and are required to write daily “thought reports.” Detainees are often kept their until the “change their thinking” and “raise their level of understanding.” China also still uses state-run mental health hospitals to keep political prisoners.

Under the current system, police can send people to labor camps for up to four years for a variety of vaguely defined offenses without having to make a case before prosecutors or judges. The policy of “reeducation through” labor has been used to imprison prostitutes, petty thieves, people regarded as a threat to the government but who committed no crime and crack down on groups such as Falun Gong and Muslim Uighars in Xinjiang.

Beijing is considering abolishing the law under which police can send suspects to labor camps or at least reforming the system so that offense are more clearly defined and the maximum term in a labor camp is less that one year.

Some people are placed under house arrest. Those under house arrest can not use the Internet, have visitors or go outside their homes unless it is approved by the government.

Chinese are attempting to reform their prisons and make them more like those in Singapore. According to a report made public in 2004: “We have introduced psychological treatment into Chinese prisons, borrowing ideas from Singapore and Canada.”

Labor Camps and Prison Labor in China

“Re-education through labor” sentences are one to three-year terms that can be handed out without trial. Labor camp sentences rarely exceed three years.At least 220,000 people were serving such sentenced in 2008. In the 1990s, Chinese-American dissident Harry Wu estimated that between 25,000 and 60,000 prisoners on at least 21 forced labor camps and 30 special farms run by the PLA were being used on an irrigation and agriculture project in the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang province financed by the World Bank.

The labor camps have traditionally supported themselves and paid the salaries of their worker by selling products like generators and farm tools — and more recently wigs and Christmas lights — made by the prisoners. These day the shabbily-made products don't sell well in the competitive markets and the camps are bringing in less money than they did. As a result the inmates are getting less food and live in worse conditions and are required to work longer hours making labor-intensive products.

"Prison labour is still very widespread and some the products end in the U.S. and Europe. It is not illegal to export prison goods to Europe, Nicole Kempton from the Laogai foundatio told The Guardian, Chinese political prisoners are sometimes forced work for no pay in Chinese factories. According to a report by Human Rights Watch Asia: "Fifty percent of Chinese rubber products come from chemical factories that employ forced labor. One prisoner who was caught trying to stuff a note inside a latex surgical glove was beaten by guards with electric batons."

A dissident who was sentenced to 11 years in a labor camp when he was 19 during an “anti-rightist campaign” under Mao told the Times of London. “I was sent to a camp in Tiantanhe outside Beijing., where I made socks. If I disobeyed I was punished with solitary confinement Others were put to work making bricks “

A prisoner at a labor camp told the Los Angeles Times, “We had to knit police uniforms, military camouflage, factory outfits and winter coats. I worked from 7 in the morning to 2 in the morning.” One worker at a "reform-through-labor" camp outside Shanghai told the Los Angeles Times said he spent up to 20 hours a day working and was sometimes beaten by guards — despite laws that prevent the overwork and maltreatment of prisoners — making Christmas lights for export to the United States. "The working conditions were very bad. There were no workshops, so we worked in our cells," he said.

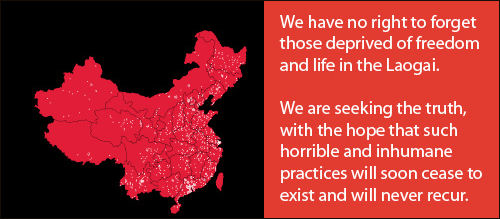

Laogai: Reform Through Labor

According the Laogai Research Foundation, founded by former dissident Harry Wu, China has incarcerated more than 40 million people since 1949. Millions died in the labor camp system known as Laogai, which translates to “reform through labor.” The group maintains that 3 million to 5 million people are still imprisoned for political reasons today “a figure rejected by Chinese officials who question Wu’s motives. “I’m not aware of those numbers,” said Wang Baodong, spokesman of the Embassy of China in Washington. “This museum is politically motivated. It’s against China and the Chinese government. He hates the Chinese government.”

Perry Link, emeritus professor of East Asian studies at Princeton, has said the laogai prison system was just as horrific as the Soviet gulag. “Whether it will attract the attention the gulag has attracted in the Western imagination, I’m doubtful. I don’t think it will,” Link told the Washington Post. “The Chinese people today aren’t ready to look squarely at this experience because they tie it too much to their own national pride. The rise of China economically and diplomatically in the world makes them very proud. For both the Soviet camps and the Nazi camps, the populations that suffered were much more willing to press the issue.”

See Harry Wu Under Dissidents

Harry Wu’s Imprisonment in the Laogi System in the Mao Era

Wu’s suffered starvation, torture and sickness while he was imprisoned in the 1960s and 70s. Larissa Roso wrote in the Washington Post, “Wu said he worked 12 hours a day on farms and in coal mines and steel mills. Food was scarce, and he sometimes ate roots, snakes and frogs. He tried to commit suicide twice, refusing to eat while in solitary confinement. His weight plummeted to 80 pounds. Throughout his imprisonment, he was allowed to write a one-page letter home every month. But he couldn’t say much to his parents and seven siblings. Police usually read the mail and censored any attempt to describe his life. It took him seven years to learn that his mother had died. [Source:Larissa Roso, Washington Post, June 27, 2011]

“I saw many people passing away,” said Wu, “Nobody cried. The brain doesn’t work. China set up the system not only to force people to make the products, to make profit for the government, but also to change people’s minds. Brain change. There is no choice of religion, no choice of political view.”

Every day, twice a day, he was asked three questions: “Who are you? What is this place? Why are you here?” The required answers: “I am a criminal. This is the Laogai. I am here to reform through labor.” “Finally, in 1979, I got a document saying they had rehabilitated me so I could go,” Wu said. “I went back to the university. And I shut up.”

Wu was a geology student in Beijing who never had been involved in political activities when he was arrested in 1960 as a “counterrevolutionary rightist,” he said. He was forced to sign papers without reading them and taken to a labor camp, a chemical factory in Beijing. “I had no choice; I signed it,” Wu recalled. “Until today, I do not know what was in that paper. They told me: “You?re sentenced to life.” “

'Gold Mining' in Chinese Prisons

Danny Vincent wrote in The Guardian: “As a prisoner at the Jixi labour camp, Liu Dali would slog through tough days breaking rocks and digging trenches in the open cast coalmines of north-east China. By night, he would slay demons, battle goblins and cast spells. Liu says he was one of scores of prisoners forced to play online games to build up credits that prison guards would then trade for real money. The 54-year-old, a former prison guard who was jailed for three years in 2004 for "illegally petitioning" the central government about corruption in his hometown, reckons the operation was even more lucrative than the physical labour that prisoners were also forced to do.” [Source: Danny Vincent, The Guardian, May 25, 2011]

"Prison bosses made more money forcing inmates to play games than they do forcing people to do manual labour," Liu told the Guardian. "There were 300 prisoners forced to play games. We worked 12-hour shifts in the camp. I heard them say they could earn 5,000-6,000rmb [£470-570] a day. We didn't see any of the money. The computers were never turned off."

“Memories from his detention at Jixi re-education-through-labour camp in Heilongjiang province from 2004 still haunt Liu,” Vincent wrote. “As well as backbreaking mining toil, he carved chopsticks and toothpicks out of planks of wood until his hands were raw and assembled car seat covers that the prison exported to South Korea and Japan. He was also made to memorise communist literature to pay off his debt to society. But it was the forced online gaming that was the most surreal part of his imprisonment. The hard slog may have been virtual, but the punishment for falling behind was real.” "If I couldn't complete my work quota, they would punish me physically. They would make me stand with my hands raised in the air and after I returned to my dormitory they would beat me with plastic pipes. We kept playing until we could barely see things," he said.

It is known as "gold farming", the practice of building up credits and online value through the monotonous repetition of basic tasks in online games such as World of Warcraft. The trade in virtual assets is very real, and outside the control of the games' makers. Millions of gamers around the world are prepared to pay real money for such online credits, which they can use to progress in the online games.

In 2009 the central government issued a directive defining how fictional currencies could be traded, making it illegal for businesses without licences to trade. But Liu, who was released from prison before 2009 believes that the practice of prisoners being forced to earn online currency in multiplayer games is still widespread. "Many prisons across the north-east of China also forced inmates to play games. It must still be happening," he said.

Pre-Trial Detention Centers and Abuse

There are 2,700 pre-trial detention centers. Suspects can be held in these places for months while awaiting trial or formal charges.

According to an article in the state-run English-language newspaper the China Daily, inmates in China’s 2,700 pre-trial detention centers are routinely bullied and tortured by fellow inmates and police.

There have been a number of inmates who have died under suspicious circumstances while in police custody, including one man charged with illegal logging who was beaten to death by three other inmates. In his case authorities initially said he hit his head playing hide and seek. Media coverage of the hide and seek death lead to an investigation of torture and bullying in Chinese prisons.

Other inmates said to have die of pneumonia had bruises and broken teeth. Chinese human rights lawyer have said inmates are routinely beaten to coerce confessions to complete investigations as quickly as possible and the detentions are regarded as “the turf” of local police.

The victims have also included minors. In Hunan Province two teenagers jailed for robbery at a juvenile reformatory died within four days of each other. One victim had a large open wound and bruises on his wrists.

Nineteen-year-old Xu Gengring, who was arrested on murdering his girlfriend, was tortured to death at detention center in Shaanxi Province. An autopsy reveled that he has been starved, his naval cavity was clogged with blood, his head was covered with bruised and his brain was full of fluid. A friend , who detained for two days, said “I was kept awake, beaten until my nose bled and my arms grew numb from carrying a pile of bricks on my back.” Six police officers at the facility were arrested. [Source: Jane Macartney, the Times of London, April 2009]

Hide and Seek Death in Chinese Prison

Li Qiaoming died from a brain injury sustained at a detention center in the south-western province of Yunnan. Police in Puning county claimed he was injured while playing “eluding the cat” as the game is known in China “ hide and seek with fellow prisoners. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, February 20, 2010]

News of the 24-year-old's death spread rapidly thanks more to the to the seemingly extraordinary explanation than the death itself. “Eluding the cat” became a buzz-phrase on the internet and the incident drew more than 35,000 comments at one site alone.

According to the Yunnan Information News, Li was arrested for illegally cutting down trees and detained on 30 January. In early February, he was rushed to hospital, but died four days later. One report cited the Puning county public security bureau as saying that Li was blindfolded and “accidentally got hurt when he ran into the wall”. In another, police apparently suggested that Li had caught a fellow prisoner during the game and the ungracious loser had punched him, causing him to fall backwards and hit his head on the sharp corner between the wall and the door.

Chinese officials have invited internet users to help them investigate Li’s death. While many assumed the notice was a spoof, more than 500 applied, and 10 joined the committee in a visit to the scene of the incident today, the Southern Metropolis Daily reported. They include an insurance salesman, a technology worker and an art student. “It's the first time in Yunnan, and even in China, that netizens have been asked to participate in an investigation,” one official said.

Officials are developing a more sophisticated approach to handling bad news in the age of the internet, recognizing it is often more effective to shape a story from the start than try to catch up when it leaks out. Since last year, they have allowed the media to react more quickly to breaking stories.

One official said he had worked hard to persuade other departments to co-operate, adding: “In the past, we did not respect the rules of journalism sufficiently and we did not understand the new media well enough. That was why we had a problem with public opinion. The purpose of this investigation is to show that there are no hidden secrets in this case.”

At least some internet users have given police the benefit of the doubt. One commented that the explanation was so absurd it had to be true.

Shourang Work Prisons and Mental Health Hospitals

“Shourang” are “study and repatriation” stations set up to process vagrants and runaways but widely used to detain almost anyone off the street on charges like not having one’s papers in order. These stations came under scrutiny when the Southern Metropolis Daily did a series of stories on them in connection with beating death of Sun Zhigang, a young graphics designers who complained about being sent to a shourang.,

The Southern Metropolis Daily then found there was a whole network of shourang and that people sent them who refused or were unable to pay fees to earn their release were sent to prison-run farms and factories, where they were put to work for little or no pay. Other articles revealed that the detention centers were profitable to police and local officials and that the system included 700 detention camps, which in some cases bought inmates to boost their profits. Outage over the “shourang” generated by the articles led the government to abolish them.

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Although China is not known for the kind of systematic abuse of psychiatry that occurred in the Soviet Union, human rights advocates say forced institutionalizations are not uncommon in smaller cities. Robin Munro, the research director of China Labor Bulletin, a rights organization in Hong Kong, said such an kang wards — Chinese for peace and health — were a convenient and effective means of dealing with pesky dissidents.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs New York Times, December 8, 2008]

“Once a detainee has been officially diagnosed as dangerously mentally ill, they’re immediately taken out of the criminal justice system and they lose all legal rights, said Munro, who has researched China’s practice of psychiatric detention.”

“In recent years practitioners of Falun Gong, the banned spiritual movement, have complained of what they call coerced hospitalizations. One of China’s best-known dissidents, Wang Wanxing, spent 13 years in a police-run psychiatric institution under conditions he later described as abusive. In one recent, well-publicized case, Wang Jingmei, the mother of a man convicted of killing six policemen in Shanghai, was held incommunicado at a mental hospital for five months and released only days before her son was executed in late November.”

See Petitioners

Black Jails

In 2008, there was report that citizens in the city of Xintain on Shandong Province who tried to petition the government were locked up in mental hospitals to keep them from airing their complaints about local injustices. Some of the detainees were reportedly drugged.

Sometimes petitioners are thrown into “black jails,” illegal detention centers, to shut them up or keep them from filing their petitions. One 59-year-old woman, whose nephew was arrested, told the Los Angeles Times she was nabbed and placed in an isolated stockroom and held for days with about 100 others and finally released with her ailing husband and then abducted again and held for several weeks in a dilapidated private home. [Source: John Glionna, Los Angeles Times, January 2010]

Humans Rights Watch has released a 51-page report on he issue call “An Alleyway in Hell: China’s Abusive Black Jails”. It cites beatings, rapes, intimidation and extortion that have taken places at them. One victim was quote in the report as saying, at the place he was sent there were “locked steel doors ad windows. We never left our rooms to eat. We were given our meals through a small window space.”

Attention to the issue was raised in December 2009 when a guard at a black jail was sentenced to eight years in prison for raping a detained college student. Nicholas Bequelin, a senior Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, told the Los Angeles Times, “As China tries to build a functioning legal system, this gnawing black hole for human rights grows right there.”

The Communist Party initially denied the jail existed but then acknowledged them in an article in the Outlook, which is owned by the official New China News Agency, saying there were at least 73 black jails in the Beijing area alone and an estimated 10,000 people have been detained in hundred of jails at one time.

According to the Los Angeles Times and Human Rights Watch the jails reportedly came into existence a few years ago after the government abolished another system that allowed officials to jail petitioners they considered a threat. Under the for-profit system private jail operators receive $22 to $44 a day per person, creating an incentive to keep victims imprisoned for long period.

A petitioner who was held for four days in a shed attached to a run-down hotel before he escaped told the Los Angeles Times, “I was held in a small room with the door locked from the outside. There was a big iron gate that cut us off from the outside world. There were guards keeping an eye on us all the time. They didn’t beat us. But I was just given green peppers with rice every day for food.” When confronted by the press the owner of the hotel said he had no knowledge of black jails. “They are help centers to assists petitioners with no transportation to get back to their homes. They’re not jails,” he said.

See Separate article under Petitioners and Black Jails

Prisoners in China

Prisoners in Beijing are given a crew cut and required to wear a uniform of coarse cotton, with vertical gray and white stripes. Many prisoners lose weight develop infected eyes and swollen hands and purple fingernails from poor nutrition and circulation.

Inmates in Beijing typically live and work in gray concrete buildings. They are allowed outside twice a week for two hour periods of open exercise. Prisoners talk to friends and family members through yellow telephone handsets on the other side of a thick plexiglass panel. The interview room consist of rows of such panels with blue plastic chairs for people to sit in. Inmates are led in a single file by a unit captain.

Prisoners in Xinjiang are given three rolls a day, and boiled vegetables and once a week get a serving or rice and meat. Some are not allowed to speak to other inmates. The punishment for speaking is standing motionless for three hours.

Shanghai prison has a 25 member symphony orchestra, with a rapist singing baritone, and thieves as sopranos. The robber conductor told National Geographic, "I was an amateur musician outside. I learned conducting here." The prisoners also make garments for exports.

In rural China, shackled prisoners carted around on the back of trucks as an example is still sometimes seen. There have been reports of women being arbitrarily detained by police and then gang raped while in police custody. In an effort to crackdown on abuses in prison, the government passed a law in June 2003, banning torture, extortion and other abuses.

Thousands of prisoners had their sentences reduced or were paroled to celebrate China’s 60th anniversary in October 2009.

Families of Prisoners in China

Families of prisoners are often ostracized even though they have done nothing wrong themselves. Children are often treated as if they were criminals even though there are laws requiring the state to take care of them. One 12-year-old whose parents were found guilty of murder told the Los Angeles Times, “Kids at school beat us because they say my mom’s a criminal. Old people are also bad to use. They say we are dirty.”

The children of prisoners are among the most neglected people in China. State facilities take care of around 1,000 kids. The other 600,000 or so are passed among relatives who don’t want them or left to fend for themselves. Sometimes these children become homeless or are treated as virtual slaves by purported caregivers. In some cases they have little choice but to turn to crime to survive.

Dissidents in Labor Camp in China

Many dissidents and political prisoners have been sent to prisons and labor camps in remote provinces such as Tibet, Qinghai (regarded as a kind of Chinese Siberia) and Xinjiang. So many prisoners were sent to Qinghai in the Mao era that a large portion of the province's population is now made of former prisoners or descendants of prisoners who had nowhere else to go.

Among the people who have spent time in Qinghai are former Kuomingtang officers, "rightist" arrested in the 1950s, former Red Guards and leaders of the Hundred Flowers, Democracy wall and Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

“Grass Soup”, an account of life in a Chinese prison by Zhang Xianlaing, has been compared to works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

On woman who spent 28 years in a labor camp breaking rocks told travel writer Colin Thubron, "In China, you must conform but I can't. That's why they think I'm mad. I challenge everything, you see, and that's the madness here. I ask Why? Why?...Why is not a Chinese question."

See Cultural Revolution

Image Sources: Laogi Museum, Wiki Commons, YouTube, Wikipedia 1) Reuters; 2) Julie Chao http://juliechao.com/pix-china.html

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2011