GOVERNMENT IN CHINA

China is a single-party, bureaucratic, authoritarian state in which capitalism is allowed to flourish but many rights that are considered basic in democracies are denied. Blending imperial Chinese traditions, Confucianism and China’s unique take on Communism, the ruling regime and party have near complete control over the government. According to the Economist, when it comes to China Orwell's “Animal Farm” “seems more like reportage than allegory."

China is a single-party, bureaucratic, authoritarian state in which capitalism is allowed to flourish but many rights that are considered basic in democracies are denied. Blending imperial Chinese traditions, Confucianism and China’s unique take on Communism, the ruling regime and party have near complete control over the government. According to the Economist, when it comes to China Orwell's “Animal Farm” “seems more like reportage than allegory."

Communist governments have has traditionally been regarded as dictatorships of the Proletariat. The first article of the Chinese constitution defines China as a “socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants.” Participation in the government is limited to members of the Communist Party and political power is concentrated in the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Social stability and the unchallenged rule of the Chinese Communist Party have been the primary goals of Chinese leaders. The system of governance in China is a combination of centralism and federalism, with a certain degree of autonomy granted to local governments, so central leaders are often unaware of what is really happening at the localities through normal bottom-up channels.

Formal Name: People’s Republic of China (Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo). Short Form: China (Zhongguo). Term for Citizen(s) Chinese (singular and plural) (Huaren). Local divisions:32 provinces and major cities (22 provinces, five autonomous regions, including Tibet, and Xinjiang, four municipalities — Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing — and two special administartion regions — Hong Kong and Macao).

Independence: The outbreak of revolution on October 10, 1911, signaled the collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), which was formally replaced by the government of the Republic of China on February 12, 1912. The People’s Republic of China was officially established on October 1, 1949, replacing the Republic of China government on mainland China.

Flag: The red flag with five yellow stars was adopted in 1949. Red is the color of Communism. The five stars (one large one and four small ones) are a symbol of China. The large star represents Communist Party leadership. The four smaller stars symbolize the worker, farmer, petty bourgeoisie and the national capitalist. Five stars in similar formation are on the Gate of Heavenly Peace at the Forbidden City in Beijing.

The National anthem “Ch'i Lai” ("March of the Volunteers") comes from the 1930s film “Children of the Storm”. The Communist Party anthem is “The East is Red!”

Articles on GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Wikipedia article on the Government of China Wikipedia ; Chinese Government site on the Chinese Government english.gov.cn

How China Is Ruled

According to the BBC: “The Chinese Communist Party has ruled the country since 1949, tolerating no opposition and often dealing brutally with dissent. The country's most senior decision-making body is the standing committee of the politburo, heading a pyramid of power which tops every village and workplace. Politburo members have never faced competitive election, making it to the top thanks to their patrons, abilities and survival instincts in a political culture where saying the wrong thing can lead to a life under house-arrest, or worse. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Formally, their power stems from their positions in the politburo. But in China, personal relations count much more than job titles. A leader's influence rests on the loyalties he or she builds with superiors and proteges, often over decades. That was how Deng Xiaoping remained paramount leader long after resigning all official posts, and it explains why party elders sometimes play a key role in big decisions. |::|

“The politburo controls three other important bodies and ensures the party line is upheld. These are the Military Affairs Commission, which controls the armed forces; the National People's Congress, or parliament; and the State Council, the government's administrative arm.” |::|

Current Chinese Government

national anthem stampsChina is regarded as an authoritarian government not a totalitarian one like the government that existed under Mao. The current government values economic growth but doesn’t tolerate dissent. It survives because it uses heavy-handed methods to put down dissent and the Chinese people are now enjoying some material benefits and have suffered much worse in the past than what they are experiencing now.

The Chinese government has a sort of deal with the Chinese people that it can remain in power as long as it brings prosperity to the people It seems to have done this by buying off the elite with business deals and opportunities to make money; placating the middle class with apartments, cars and travel; and raising hopes among the poor with chances to seek a better life. Perhaps what is most remarkable about Beijing’s hold on power is that it is able to keep it up.

The Chinese government is very opaque. It is difficult to see how decisions are made and how policy is shaped. What one usually sees are rubber stamps of decisions that have been made behind the scenes. A lack of accountability, systematic corruption throughout party ranks and the release of inaccurate statistics for political purposes are also characteristics of the regime.

Changes tend to be made in an incremental way after a consensus has been reached among the top leaders. Frederick Teiwes, a China expert at the University of Sydney, told the New York Times, “China has a tyranny of the middle. From the perspective of the leadership, things are going pretty well. They all want stability.”

Views on the Chinese Government

A poll conducted by the Pew Research Center before the 2008 Olympics found that 86 percent of the Chinese interviewed were happy with the direction that China was going, up from 48 percent in 2002, and two thirds thought the government was doing a good job. These were much higher numbers than were found in the United States and European countries on the same issues. In the United States only 26 percent were happy with the direction the country was going. The survey questioned 3,212 Chinese in 16 dialects across the nation. Approval ratings of the government have increased as the economy has improved but the people surveyed did have issues with corruption, environmental problems and inflation.

New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote, “One-party autocracy certainly has is draw backs. But when it is led by a reasonably enlightened group of people, as China is today, it can also have great advantages.”

The Communist system in China depends on legions of police, local party and government officials to enforce Beijing’s policies and squash dissent. While the perception of China from the outside is one of authoritarian control, the reality is that the social and political balance in the country is more fragile.

Historian Francis Fukuyama of Johns Hopkins wrote: “A lack of constraint by either law or elections mens accountability flows only in one direction, upwards towards the Communist Party and central government and not downwards toward the people. There is a whole range of problems in contemporary China regarding issues like corruption, environmental damage, property rights and the like that cannot be properly resolved by the existing political system.”

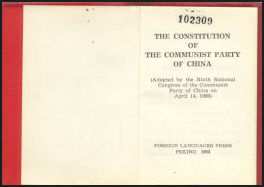

China's Constitution

The Constitution of the People's Republic of China was ratified in 1982 and amended and adopted at the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China on October 21, 2007. The constitution enshrines the values of “security, honor and interests of the motherland.” It includes Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. There was some discussion about Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” being included.

The Chinese constitution has been called a “collection of slogans.” It purportedly offers the freedoms of speech, press and association. Many of the laws are not all that different from laws in Western countries the only problem is that these laws have traditionally been ignored, interpreted in strange ways or not enforced.The constitution is not allowed to be used for arguments made in court and courts have no right to review constitutionality. This weakness is based on judicial interpretation by China’s top prosecutor in the 1950s that regular laws were detailed and sufficient. The Communist Party is viewed as the final arbitrator of the law.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has had four constitutions, promulgated in 1954, 1975, 1978, and 1982. The current version, adopted on December 4, 1982 by the Fifth National People’s Congress of the PRC, has since been amended four times, in 1988, 1993, 1999, and 2004. It was created as a part of the reform program in which China moved away from the planned socialist economy and toward a mixed economy in which the market and private property have played increasingly large roles. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Amendments have been added in the 2000s that guarantee private property and human rights. See Private Property, Economics, and Human Rights.

See Constitution of the Communist Party of China [PDF], Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu and People's Republic of China, Constitution, Human Rights Library, University of Minnesota hrlibrary.umn.edu/research

Women in Government in China

Former Vice Premier

Wu Yi

Women account for around 20 percent of the NPC members and less than a fifth of Communist Party members. As of 2003, there were only five women in the high-ranking 198-member Central Committee and only one woman in the 24-member Politburo. There are a fairly large number of female party officials but they generally don't have high-level jobs. In 1994, 32.6 percent of the Chinese officials were women but only 10.7 percent of the officials above the county level, just one of the country's 13 state councilors and three of its 40 ministers were female.

In August 2005 China promised to improve women’s representation in politics.

Vice Premier and Health Minister Wu Yi is the highest-ranking women official in China and the only female politburo member. Appointed health minister during the SARS crisis, she is very popular and has a reputation for carrying about people. Some think she is a reincarnation of the Buddhist goddess of Mercy, Kwan-yin

Wu Yi is an Oxford-educated economist and former petroleum engineer. She represented China during trade negotiations between China and the United States in 2006. One U.S. official described her as “an impressive interlocutor — very direct and very capable of getting things done.” Wu worked under Zhu Rongji. Zhu and Wu worked hard to pave the way for China’s entrance into the WTO.

In 2007, Wu Yi was ranked as the second most powerful woman in the world for the second year in a row by Forbes magazine, placing behind German Chancellor Angela Merkel and ahead of U.S. Secretary of State Condolezza Rice.

Wu resigned as a member of the Political Bureau of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2007 and retired as Vice Premier in March 2008. She said that when she retires she doesn’t want to work for any government-related organizations or public organizations. “Please forget about me completely after I’ve gone,” she said.

Liu Yandong resides on the politburo as state councilor (and politburo)

Zhao Suping, mayor of a city in Henan province, was one of the few women studying at the Central Party School in 2009. She acknowledged the lack of senior women cadres but said lack of diversity was an international problem. “Women are relatively poorly educated and traditional concepts and ideals still prevent women going into the career,” she said. “There are also problems in the recruiting and promotion process.” [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, June 30, 2010]

Head of Government in China

Current leader Hu Jintao with

former leader Jiang Zemin

The primary leadership positions in China are: 1) the President; 2) the General Secretary of the Communist Party; and 3) the Chairman of the Central Military Commission, the de facto head of the military. China has a Prime Minister but he is generally regarded as the No. 2 or No. 3 person in power. He is nominated by the President and confirmed by the National People’s Congress. The chairman of the National People’s Congress is considered the No. 2 leader in China. These days the President is responsible for domestic and foreign policy. The Prime Minister is largely regarded as China’s economic czar. He is responsible for economic policy.

The presidency is often regarded as the weakest of the three primary leadership position. The leadership of the Communist Party is essential because the party rules the country. Leadership of the military is also essential because it provides the muscle behind the party. Both Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin retained the position of Chairman of the Central Military Commission as way of maintaining power behind the scenes after giving up the positions of president and party leader.

Some principal leaders have held all three primary leadership positions; some haven’t. Traditionally the three primary leadership positions and the Prime Minister job were held by different people. Under Deng Xiaoping, Hu Yaobang was party chief and Zhao Ziyang was prime minister and Lia Xian Nian was President . To bolster his relatively weak position Jiang Zemin took the Presidency, Party Secretary and top military job, a trend continued by Hu Jintao.

The Communist leaders of China are for the most part former engineers. Rana Foroohar wrote in Newsweek, “China’s faith in its ability to mold markets may derive from the fact that its leaders are mostly engineers, trained to build from a plan. Eight of nine top party officials come from engineering backgrounds, and the practicality of their profession may help explain why they didn’t buy into risky (and Western) financial innovation. These ruling engineers preside over a system that is highly process oriented and obsesses with performance metrics.”

See Choosing New Leaders Below

Being a Leader in China

Ordinary people know little about the lives of their leaders, but there are lots of rumors. The typical 20,000 word presidential speech has been called an exercise in tautology. Steven Clemons, author of the popular blog the Washington Note, wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Those leading the Chinese government, for the most part, put a premium on opaqueness and disdain transparency, cautiousness is rewarded; risk-taking is punished. But perhaps most importantly” especially in international affairs “they view solicitiness and vacillation as weaknesses.”

As of 2009 eight of China’s top nine leaders (the members of the politburo) — including President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao — were engineers. But that seems likely to change as many of the party’s top rising stars — including Wen’s likely successor Li Keqiang — got their top degrees in something other than engineering.

Leaders have to rule by consensus. Leaders shore up their support and power bases. Some openness is tolerated as long as the party can control and limit it.

Evan Osnos wrote in the New Yorker: “China is a dictatorship without a dictator, having abandoned totalitarianism in favor of something far more difficult to define: a one-party state run by a committee of studiously bland apparatchiks, terrified of political challengers and convinced that its reign rests on continuing to raise the living standards of the people. Today's Chinese disciples seem far too knowing and interconnected to have much in common with their predecessors under the Cultural Revolution, and yet the memory of their society's dark potential still throbs like a phantom limb. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, January 10, 2011]

Robert Lawrence Kuhn, author of Book: “How China’s Leaders Think: The Inside Story of China’s reform and What This Means to the Future” told the Los Angeles Times, “All the members of the senior leadership believe the dominance of the party absolutely essential for the greater good of society. But I think they do realize they need to make some course adjustment to reset perceptions of China.”

WikiLeaks did not release anything that interesting about senior Chinese leaders. The only revealing information was a confidential cable from May 9, 2009, in which Japan’s then-Prime Minister Taro Aso reports that Premier Wen Jiabao was “very tired and seemed under a lot of pressure” while President Hu Jintao seemed “confident and relaxed.” Perhaps the most interesting leaks was a diplomatic cable by by Former Australian Prime Minister Keven Rudd, who described Chinese leaders as “paranoid” about Taiwan and Tibet and told the United States to use force against China “if everything goes wrong.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, November 29, 2010]

Book: “How China’s Leaders Think: The Inside Story of China’s reform and What This Means to the Future” by Robert Lawrence Kuhn, an investment banker and advisor to the Chinese government. “The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers” by Richard McGregor (Harper, 2010) McGregor has been a reporter with the Financial Times for some time. The Washington Post called the book “illuminating and important.”

Standing Committe of the Politburo

Chinese Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee

The Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party is the country’s effective ruling body. It is headed by the President and used to have nine members but in November 2012 the number was reduced to seven. The Politburo (Political Bureau) is made up primarily of long-time party faithful who have various titles which often have little relation to how much power they possess. It has 24 members and one alternate.

The powerful State Council is China’s highest administrative body. The equivalent of the Cabinet, it make proposals to the Standing Committee of the Politburo and is appointed National People’s Congress (NPC). Other top leaders include ministry heads, provincial leaders and mayors of major cities. A dark blue suit with a red tie is the standard attire for these top party officials.

Chinese Central Committee

Another important political organization in China is the Communist Party’s Central Committee, which is made up primarily of provincial party leaders and important party members chosen from among the delegates at the party congress. The Central Committee has 371 members (204 members and 167 alternates in 2008, the numbers change) and includes China’s top leaders and important leaders from the party, the state and the armed forces. Elected for five year terms, the members meet in a plenary session about once a year .

All major policy decisions in China are made at the top by the Politburo and the Central Committee. Technically, the Central Committee is “elected” by the delegates, but members are largely pre-selected by party elites. A newly formed Central Committee chooses the ruling Politburo, which now numbers 25, and the nine-member Politburo Standing Committee.

Political power is formally vested in the CCP Central Committee and the other central organs answerable directly to this committee. The Central Committee is elected by the National Party Congress and is identified by the number of the National Party Congress that elected it. Central Committee meetings are known as plenums (or plenary sessions), and each plenum of a new Central Committee is numbered sequentially. Plenums are to be held at least annually. In addition, there are partial, informal, and enlarged meetings of Central Committee members where often key policies are formulated and then confirmed by a plenum. [Source: Library of Congress]

“The Central Committee's large size and infrequent meetings make it necessary for the Central Committee to direct its work through its smaller elite bodies — the Political Bureau and the even more select Political Bureau's Standing Committee — both of which the Central Committee elects. In the 1980s the Twelfth Central Committee consisted of 210 full members and 138 alternate members. The Political Bureau had twenty-three members and three alternate members. The Standing Committee — the innermost circle of power — had six members who were placed in the most important party and government posts.

“In the 1980s special conference called National Conferences of Party Delegates were held. These national conferences of delegates appeared to be more authoritative than regular plenums.

Party Congress in 2007

Party Congresses in China

Party Congresses are held every five years in the Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The last one, the 17th, was in autumn 2007. The next one, the 18th Party Congress is in 2013. The event lasts for about a week. More than 2,200 representatives attend. They are selected by the party congresses in each province.

The Party Congress is arguably the most important event on the political calendar because it is the showcase event for the Chinese Communist Party and the Communist Party is the most powerful institution in China. Party Congresses formally ratify laws, establish policy, affirm leadership positions and select members of the Central Committee, Politburo, and Politburo Standing Committee. Important speeches are given. The main meetings are televised nationwide.

Party congresses put their stamp of approval on policies and candidates already vetted by the Central Committee. Most decisions are made before the congress during months of negotiating between the members of the Central Committee, the Politburo, and the Politburo Standing Committee, with intense rounds of deal making taking place in the weeks before the congress begins. During the congress endorsements are often made with a show of hands.

Describing the unveiling of the Standing Committee at the Party Congress in 2007, Edward Cody and Maureen Fan wrote in the Washington Post, “Hu led the parade before the cameras, wearing his usual blue suit. The eight other committee members trailing behind also wore blue suits, most set off by red or maroon ties...They stood stiffly at attention, clasping their hands alternately in front and back, as Hu addressed journalists in the Great Hall of the People. As Hu introduced them one by one, each man stepped forward and a gave a little wave, like a beauty pageant contestant acknowledging applause.”

Plenums in China

Plenums are closed door meetings conducted by the Central Committee that last for around four days and are held once or twice a year. They can be very important. One in 1978 launched China’s economic reforms and paved the way for China to become the economic powerhouse that it is today.

Plenums are held amidst tight security and heavy secrecy at the Great Hall of the People. No one except the participants knows what goes on there. Plenums are generally attended by the members of the Central Committee. Policy rubber stamped at Party Congress are often shaped during the plenums. The content of the meetings is kept tightly under wraps. There are no details in the press about the agenda or discussion just some vague statements about broad topics. Whatever information is released is released after the meetings are over.

17th National Congress of the Communist Party in October 2007

Plenums that endorse five year plans, held every five years, have traditionally been important political events. The Central Committee members meet and endorse the five-year plan for the next five years.”The Fifth Plenum of the 16th Communist Party Central Committee” was held in September 2005. It was attended by 500 people, 200 committee members and presumably their aides and lower-ranking officials. They endorsed the five-year plan for 2006 to 2010. The plenum before that, “The Forth Plenum of the 16th Communist Party Central Committee,” was held in September 2004 and the one before that was in October 2003.

National People's Congress, the Chinese Legislature

The National People's Congress (NPC) is supposed to be China’s democratically-elected equivalent to the Congress in the United States. In truth it has little power and its members are not democratically selected. Instead they are chosen by the Central Committee, which essentially follow decisions made by the Politburo.

Even though the NPC technically has the power to amend the Constitution it is essentially a rubber stamp organization whose members obediently vote the party line. Members don’t have to be members of the Communist Party but about three fourths of them are. Only 18 percent are “vanguards of the proletariat” — workers and farmers. The NPC is officially powerless but its advice is seen as a way of keeping the legislature and government in touch with the masses and getting feedback from the ordinary people. It is also a chance to see China's most influential players gather together under one roof, and analysts will be looking for clues about who may access the top echelons of power.

The NPC is made up of about 3,000 delegates. The annual meeting in Beijing, which is last for two weeks and is held in March, serves more as a grand rally exalting the ruling party than a forum for real parliamentary debate. The is marked by strict adherence to protocol and attended largely by colorless officials. Some meetings are held in huge halls of the Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square that hold hundreds or thousands or members. Other meeting rooms look like lobbies in shabby Chinese hotels with all the chairs lined against the walls. The meeting brings together delegates from across the country — many of them in traditional dress representing their home regions — in a colourful display of national unity. Questions about the governance and security of those regions are sometimes raised. [Source: AFP, New York Times, March 1, 2012]

The National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference are held around the same time. Together they are known as the lianghui, or “two meetings.” Both are attended by delegates from throughout China. Delegates often discuss the most important political and economic issues in their provinces, regions or cities, though their ultimate purpose is to approve policy decisions already made at the highest levels of the Communist Party.

Security in Beijing is high during the annual meetings of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. During this time, people deemed to be potential troublemakers are kept under close watch by the police. A security force reported to be 700,000 strong was mobilized for the 10-day session of the National People’s Congress in 2010. In March 2007, hundreds of thousands police and volunteer helpers took up positions in Beijing to make sure that session went smoothly. Half a million volunteers patrolled neighborhoods to ensure there were no “outstanding public security problems and accidents.” Many of the police worked on their days off.

The chairman of the National People’s Congress is regarded as the No. 2 leader in China. Party officials make up the single largest legislative block.

See Democracy

National People's Congress Members

The NPC is the world's largest legislature. It has 2,000 to 3,000 unelected deputies (2,985 in 2007 and 2,987 deputies in 2008) from 32 provinces and major cities, including ethnic minorities who show up at the meetings dressed in their traditional costumes and headgear. The members are indirectly elected to 5 year terms and come from all over China for the annual legislative sessions.

Delegates help to provide atmosphere and pageantry at party congresses, but their impact on decision-making is minimal. The decisions have already been made. Most deputies are veteran local government, military officers or industry officials. They are treated well and have all their expenses to Beijing paid for the congress. On their duties, the chairman of the Standing Committee said, “Being subservient to and serving the work of the party’s choices is the fundamental prerequisite for doing god legislative work.”

A deputy from a rural area of Sichuan interviewed by the Washington Post said she had been selected by local officials to attend the congress and spent much of her time at the congress in discussions on practical matters like improving crop yields. She offered no policy proposals of her own but did sign on to some suggested by other deputies. She, like other deputies, refuses to criticize the government but is willing to express her gratitude for all the improvements the government has made to her village and region.

Activities of the Chinese Legislature

The National People’s Congress meets annually in March in the Great Hall of the People for a 12-day session. Heavy politicking is always high on the agenda: to make sure the Party policies are approved and make sure message is brought to the provinces. Leaders sure up their support and power bases. Some openness is tolerated as long as the party can control and limit it. Most Chinese have no idea who their representatives are and have little interest in their meetings.

The Great Hall of the People is the meeting place of the National People's Congress. Occupying almost the entire western side of Tiananmen Square, it is a Stalinist monolith with 300 rooms and 170,000 meters of floor space and was built in only 10 months in 1958 and 1959. Some of the rooms are quite large and lavish. Other look like lobbies in shabby Chinese hotels with all the chairs lined against the walls. Each year in March the NPC meets in the "The Ten Thousand People's Meeting Hall," which seats 10,052 people. Important overseas dignitaries are greeted in a banquet hall large enough to accommodate a feast for 5000 people or a cocktail party for 10,000 people.

Meetings are always scripted. Prearranged agendas are endorsed. Preliminary votes are often held to make sure everything goes to plan. Legislators listen to long speeches and clap on cue. Sometime debates are held with clearly delineated limits. Leaders listen to concerns of the delegates, sometimes in public. But more often the sessions are closed. Describing what goes on one delegate told AP, “We’re making our contribution to the nation’s economic development and the development of a well-off society in an all-around way.”

A typical vote is 2,826 in favor, 37 opposed end 22 abstentions. Because only half of Chinese are able to speak Mandarin and 55 ethnic minorities are found in China, a team of more than 180 interpreters — who speak Tibetan, Uighur, Kazak, Korean, Mongolian, Yi, Zhuang and other languages — is put to work to make sure all members know what is going on.

When Party and People’s Congresses are in session security is tightened around Beijing. Tiananmen Square is sealed off and anyone regarded as suspicious or threatening is carted away. Soldiers ring the perimeter of the square, which becomes a big parking lot for the buses that bring in the delegates. Other security measures include bomb-sniffing dogs, car searches, removing potential protesters from the city, bans on hot air balloons and parachutists, and thorough cleaning of vegetables to make sure no one gets sick.

Chinese People’s Political Consultive Conference (CPPCC)

The Chinese People’s Political Consultive Conference (CPPCC) is an advisory body to the NPC made up of business people, religious leaders, academics, athletes and celebrities and other people of influence. It is officially powerless but its advise is seen as a way of keeping the legislature and government in touch with the masses and getting feedback from the ordinary people.

The CPPCC is the legislature’s top noncommunist advisory body. It’s main meeting often precedes the opening the National People’s Congress. Party members only account for 40 percent of the CPPCC’s delegates.

The CPPCC had 2,237 members in 2008. In one speech a top official said the delegates should “play their roles as important democratic channels for the expanding orderly participation in political affairs by people from all walks of life.”

At CPPCC meetings there are debates about functions of government bodies but no debate on the parent’s role in that body. Minxin Pei of the Carnegie Endowment for Peace told the Washington Post “It only consultive democracy. They party says, 'Once we consult with you, that’s a democracy.”

Russel Leigh Moes, a Beijing-based political expert, told the Washington Post, “The myth about the system is that there is not a diversity of views, but there are. But there are some big questions not talked about. You cannot question the party’s authority over everything.”

Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), China's top political advisory body, met in March 2011.

Central Organization Department and the Communist Party Bureaucracy

The Central Organization Department is the party's vast and opaque human resources agency. Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “It has no public phone number, and there is no sign on the huge building it occupies near Tiananmen Square. Guardian of the party's personnel files, the department handles key personnel decisions not only in the government bureaucracy but also in business, media, the judiciary and even academia. Its deliberations are all secret. [Source: By Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, July 25, 2010]

If such a body existed in the United States, Richard McGregor wrote in his book “ The Party” it "would oversee the appointment of the entire US cabinet, state governors and their deputies, the mayors of major cities, the heads of all federal regulatory agencies, the chief executives of GE, Exxon-Mobil, Wal-Mart and about fifty of the remaining largest US companies, the justices of the Supreme Court, the editors of the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the bosses of the TV networks and cable stations, the presidents of Yale and Harvard and other big universities, and the heads of think-tanks like the Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation."

Foreign policy is ultimately crafted not by the foreign ministry but the party's Central Leading Group on Foreign Affairs, and that military matters are decided not by the defense ministry but by the party's Central Military Commission. These and other party groups meet in secret.

In “ The Party” McGregor described the existence of a network of special telephones known as "red machines," which sit on the desks of the party's most important members. Connected to a closed and encrypted communications system, they are China's version of the "vertushka" telephones that once formed an umbilical cord of party power across the vast expanse of the Soviet empire. All governments have their own secure communications systems. But China's network links not just ministers and senior party apparatchiks but also the chief executives of the biggest state-owned companies — businessmen who, to outside eyes, look like exemplars of China's post-communist capitalism.

Five Year Plans in China

The Five-Year Plan is a throwback to central planning but a useful roadmap of Communist Party goals. They usually set ambitious targets that are not always been met or inspire officials to fudge data so they are met. Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, they usually offer a sheaf of paeans to the Communist Party’s stewardship of the nation, with staggering statistics to support them. China’s international prestige “grew significantly”; its “brilliant achievements” in economics “clearly show the advantages of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian: “The five-year economic plan, once an arcane exercise in communist fiat, has big implications for the outside world. It could affect the color of the sky, the planet's temperature and the welfare of billions of people beyond the jurisdiction of the country's mandarins. An army of cadres, officials and academics have spent years laying groundwork for the plan — the 12th since Mao Zedong started Soviet-style strategising in 1953. They have one of the world's most ambitious administrative tasks: plotting a course for a continent-sized nation, a 1.4 billion population and a $5 trillion economy that is growing at double-digit speed every year.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; BBC; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016