DEMOCRACY IN CHINA

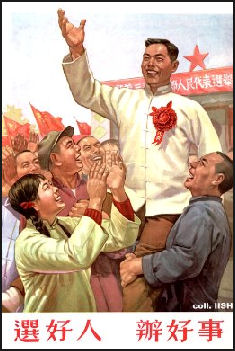

Mao Zedong voting

In a 2½-hour speech before the 17th National Congress in October 2007, Chinese President Hu Jintao used the word “democracy” 60 times. Apparently clarifying what Hu meant, Xinhua ran a story that said China would continue to develop democracy “with Chinese characteristics” under the “leadership of the Communist party.”

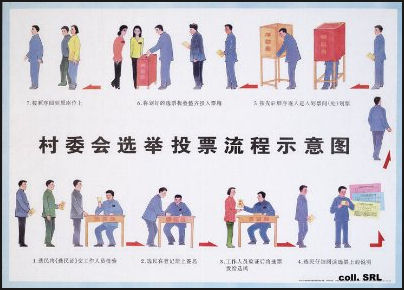

There is some democracy on the local level. Hundreds of millions in China already go to the polls to choose low-level representatives. But efforts to promote and expand village elections widely lauded in the 1990s appear to have stalled. But still the government has no system of accountability, no system of checks and balances, no watchdog agencies and no free press. Discussions and decision making are conducted behind closed doors.Many have wondered why elections have not been held for higher-level positions. Democracy is promoted mainly as a way of giving the Communist Party credibility, addressing critics from abroad and dealing with low- and mid-level corruption ( See Elections).

The government however is more responsive than it used to be. Newspapers do report about injustices and corruption. Citizens can file complaints. Although this system is still quite flawed and the complaints are often ignored, government agencies respond to some degree to public opinion especially when they are pressured to do so by central government directives. The threat of wider social unrest, spurred by corruption and income inequalities created by China's rapid economic boom, is what lies behind Beijing's push for democratic reform. There seems to be a certain understanding among today's leaders that, without democratic reform, the country risks widespread social unrest that could ultimately bring down the party.

Recent experiments, such as the use of deliberative democracy in setting budgets and awarding a greater say in the selection of local party secretaries, offer clues to possible routes towards or alternatives to a multi-party system. Yet so far, they stand alone.

George Yeo, Singapore’s foreign minister, wrote in Global Viewpoint, “China is experimenting with democracy at the lower levels of government because it acts as a useful check against abuses of power. However, at the level of cities and provinces, leaders are chosen from above after careful canvassing of the views of peers and subordinates.”

Articles on GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Article on Democracy in China /tsquare.tv ; 2008 Article in Foreign Affairs foreignaffairs.com ; Chinese Government Articles on Democracy english.peopledaily.com ; Carter Center China Program cartercenter.org ; Wikipedia article on the Government of China Wikipedia ; Chinese Government site on the Chinese Government english.gov.cn

Socialist Democracy

Peasant election propaganda poster

Chinese leaders sometimes use the term “socialist democracy” which roughly means allowing public debate on certain topics and under strict limitation, without challenging the mandate of the Communist Party to rule over all institutions of government.

In September 2010, President Hu Jintao gave a speech in Hong Kong in which he called for new thinking, saying, “There is a need to expand socialist democracy ... hold democratic elections according to the law; have democratic decision-making, democratic management as well as democratic supervision; safeguard people’s right to know, to participate, to express and to supervise.”

In February 2011, Hu told the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal, “We will define the institutions, standards and procedures for socialist democracy, expand people’s ordinary participation in political affairs at each level and in every field, mobilize and organize the people as extensively as possible...and strive for continued progress in building socialist political civilization.”

The five-year plan issued in March 2011 contained a section on "developing socialist democratic politics," where it indicated that Chinese citizens had "the right to know, the right to participate [in politics], the right to express themselves, and the right to supervise [the government]." It also pledged that Beijing would push forward "democratic elections, democratic decision-making, democratic management and democratic supervision" according to law.” [Source: Willy Lam, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, March 25, 2011]

Democracy with Chinese Characteristics

Former maximum leader Deng Xiaoping was quoted in 1987 as saying there would be national elections in 50 years, by 2037. So China may be right on schedule with its democratic trajectory.

The Chinese government sometimes talks about democracy with Chinese characteristics. :My problem is that no one really can offer a definition of what that is,” said Dr Yawei Liu of the Carter Center's China Program, which works with Chinese officials to improve elections and civic education. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, May 20, 2009]

“If you look at civic activism, what's taking place in cyberspace and what's going on in 600,000 villages in China [with grassroots elections] they all seem to indicate there's still a push from the top and most importantly from the bottom to expand political reform The problem is how grassroots efforts could be elevated to a higher level and whether the leadership has the wisdom and courage to move forward with an agenda.” [Ibid]

In Shanghai there is sort of Democracy Wall on Nanjing Lu, across from the Shanghai Exhibition Center, where residents air their grievances about issues that bother them such razing of old neighborhoods, land seizures and sweetheart deals made with corrupt officials.

Vertical Democracy in China

In their book, “China’s Megatrends: The Eight Pillars of a New Society”, futurologist John Naisbitt and his wife Doris argue that that China has developed a different — and better — form of democracy, which they call “vertical democracy,” William A. Callahan wrote in a review of the book. “Freedom, they argue, means something different for Chinese people: social order and harmony. The focus of democracy thus shifts from individual choice to group harmony. The main task of vertical democracy is not to represent the people’s will, but to harmoniously balance top-down and bottom-up forces. Top-down refers to the CCP leadership’s plans and policies; yet the book’s examples of bottom-up influence are not so clear: mass demonstrations were okay when Shanghai residents successfully stopped the East China Maglev Project (2007-08), but were a threat when they took place in Tiananmen Square in 1989. [Source: William A. Callahan, China Beat, November 15, 2010]

For all this talk about the importance of bottom-up influence, China’s institutional structures for listening to popular needs, concerns and ideas are quite weak, and it seems that the CCP decides what is “acceptable” bottom-up activity ex post facto — which is hardly a good formula for building trust. The Naisbitts’ new model of good governance thus begs many questions that are familiar to both pundits and political theorists: “Who watches the watchmen?”

Political reform poster

Evolution of Democracy in China

Chinese leaders have said that they welcome more democracy in China but they want to proceed slowly and cautiously so as not to destabilize the country or cause other problems. Beijing has said repeatedly it wants to avoid the situation that occurred during and after the break up of the Soviet Union.

There were efforts to reform and democratize the Chinese government in the 1980s but these were largely halted after Tiananmen Square and have been stalled or slow to develop since then. In the meantime the government has become more skilled at maintaining power while placating the masses and holding off criticism from abroad. A great deal of time and energy has gone into strengthening security forces that can put down civil disturbances, restricting the media and Internet and allowing just enough freedoms and expressions to keep criticism from growing too intense.

The conventional wisdom in much of the West has been that the market liberalization will lead to democracy. The reasoning has been that the opening of markets will lead to the creation of an educated and business-mined middle class over time and they would demand more rights and a say in political matters that affect their lives.

China seems to have defied the conventional wisdom that economic growth, a growing middle class and trade with the outside world will somehow produce democracy and political reforms. There is no evidence that a growing middle class is demanding more democracy or political reforms or have become organized in any kind of meaningful way.

The leadership in China has been very effective short-circuiting the elements of market economics that leads to democratization, namely pacifying the masses with material wealth, allowing some freedoms that don’t threaten the government’s hold on power, targeting repression to trouble spots, introducing some social benefits such as education and health, and effectively using the media.

Volunteerism and Parents Groups in China

Parents group such as those that lost children in the Sichuan earthquake and Tiananmen Square and those whose children were sickened in the tainted milk scandal have been allowed to organize and operate relatively freely in part because these groups have the sympathy of the general public and to crackdown on them could cause widespread resentment among ordinary people who have become increasingly well-informed and connected in the Internet age. These parents groups are among the first groups that have been allowed to operate beyond the control of the government.

The government has tried to clamp down on such groups by following and tracing the calls of leaders and closing and blocking their websites but been outwitted by leaders who communicate with card cell phone that can’t be traced and meet and statehouses and communicate through websites that have foreign sponsors and can’t be touched by Chinese censors.

The wave of volunteerism and willingness to press the government for the right to volunteer during the Sichuan earthquake (See Sichuan earthquake) was seen as sign of taking civic responsibility and moving towards democracy. One analyst told Time, “It’s a major leap forward in the formation of China’s civil society, which is vital for China’s democratization process.”

See Elections, Separate Section

Why Democracy is Not Taking Hold in China

In his book “The China Fantasy” James Fallows writes that the assumption that China will evolve into a democracy as the middle class grows is based on false assumptions. He argues that the middle class, especially young professionals, have been the prime beneficiaries of China’s prosperity and are thankful to the present government for providing it. And, they have the most to lose if reformers appear on the scene and change government is policy to, say, helping the rural poor at the expense of the urban rich.

Francis Fukuyama, professor of international studies at Johns Hopkins, agrees. He wrote in the Japanese newspaper the Daily Yomiuri, “Upwardly mobile Chinese, buying their first car or condominium, are above all interested in stability. What would threaten the new middle class’ property today is precisely the emergence of a broader democracy. The reason is that China remains a hugely unequal society in which hundreds of millions of people have been left behind...Were China to democratize today, the political consequences would likely threaten middle class prosperity, if not political stability in general...Democracy will be potentially destabilizing until the large mass of rural poor in China come to share in the prosperity enjoyed by the elites and middle class.”

Urban young adults are surprisingly apolitical. One young account executive for the foreign advertising firm Ogilvy and Mather told Time, “There’s nothing we can do about politics. So there’s no point in talking about or getting involved. Events like the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward are viewed as ancient history. Some even say the crackdown at Tiananmen Square, as one young woman told Time, was “certainly needed.” On young woman told Time. “Our life is pretty good. I care about my rights when it comes to the quality of a waitress in a restaurant or a product I buy. But when it comes to democracy and all that, well...That doesn’t play a role in my life.”

Many you Chinese have a negative view of American democracy. A student at Fudan University in Shanghai told The New Yorker, “Chinese people have begun to think. One part is the good life, another part is democracy. If democracy can really give you the good life, that’s good. But, without democracy, if we can still gave have the good life why should we choose democracy?”

Many think that China will evolve into some kind of mix between autocratic control and Western-style democracy. China expert Sidney Rittenberg thinks that China is capable of producing a kind of democracy that blends Confucian values and modern consumerism and is uniquely Chinese. He told the Los Angeles Times, “It may be a pipe dream, but I think it’s possible in this country, over time, they will create something new. They’ll create a kind of democratic political system...something involving consultations, a lot of meetings in advance. But it will be a different kind of democratic system.”

Supergirl Idol and Democracy

The Chinese version of “American Idol” — “Supergirl Idol” — has been enormously popular, attracting up to 400 million viewers, nearly a third of the population of China, with many of them voting for their favorites with text messages. The winner of the contest, Li Yuchan, who received 3.5 million text message votes ahead of 3.2 million for her nearest rival, became so popular she took the No. 6 spot on the Forbes list of China’s hottest and richest celebrities.

The sponsor of “Supergirl Idol”, the milk company Mengniu, saw it sales increase fivefold while the show was aired. “Supergirl Idol”, which originated on a Hunan satellite channel, was so successful that in August 2007 the Chinese government labeled the show “coarse” and shut it down. The crack down, Beijing said, was part its campaign against the declining quality of television programming but many think that it was really shut down over worries by the government that viewers being allowed to vote for favorites on a television show could lead to demands for democracy.

By that time American-Idol-style talent shows hade became all the rage in China. By one count there were of 50 of them on satellite television at one time and dozens more on regular television. One of them, “Happy Boy Voice”, was criticized by the government in April 2007 for showing screaming fans and tearful losers. The show's producers was told to broadcast more “healthy” songs and “mainstream” clothes and to remove “vulgarity, weirdness and low taste.” A statement released by SARFT said, “The design of the show is coarse. The judges’ behavior lacks grace....The songs performed are vulgar.”

In 2006, the government passed regulations limiting American-Idol-style shows to 2½ month runs and said no more than three satellite television shows could broadcast them during the same time slot. In September 2007, the government banned voting by mobile phone on American-Idol-style shows and bumped such shows off of prime time. According to 1½ page order issued by SARFT the action was taken because the shows “suffered" from “problems of cheap tone, betraying the fundamental position of being positive, healthy and striving for improvement, damaging the image of television broadcasting.”

Han Han on Revolution, Democracy, Freedom

Peter Ford wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “Han Han, a Chinese race-car-driver-turned-political-polemicist who has become one of the country’s most popular bloggers, has unleashed a firestorm on the Web with a volley of edgy essays over the weekend. The essays are on three of the government’s least favorite subjects: “On Democracy,” “On Revolution,” and “On Wanting Freedom.” [Source: Peter Ford, Christian Science Monitor, December 27, 2011]

The outspoken Mr. Han reaches more than a million followers and readers whenever he sounds off, which gives him a degree of leeway that the Chinese censors do not grant to everybody. And his popularity means that all of a sudden the sensitive subjects he broached have moved out of the shadows of intellectual or dissident websites into the glare of the Chinese Web’s most visited portals.

Han is all for increased freedom of expression. “I believe I can be a better writer, and I don’t want to wait until I am old,” he says. But he is ambivalent about democracy in China because he doubts whether enough Chinese people have sufficient civic consciousness to make it work properly, and he is against a revolution because “the ultimate winner in a revolution must be a vicious, ruthless person.”

Ordinary people’s “quest for democracy and freedom is not as urgent as intellectuals imagine,” he argues, and one-person-one-vote elections “are not our most urgent need” because “the ultimate result would be victory for the Communist Party” — the only institution powerful enough to buy off all the voters, he says. Instead, he advocates step-by-step reforms to strengthen the rule of law, education, and culture. That’s an approach that the government claims as its own, and Han’s essays have drawn a fair bit of flak from other liberal commentators. “His stance is too close to that of the authorities,” sniffed dissident artist Ai Weiwei on his blog. “It’s like he has surrendered voluntarily.”

Han writes in a casual, immediate style that appeals to younger readers, but his gadfly commentaries are pretty lightweight and not always intellectually coherent and he often says things on his blog that he is lucky to get away with. (Ai Weiwei spent nearly three months jailed in solitary confinement this summer for criticizing the authorities.) Still, as I read Han’s essay on revolution, something chimed with what I had come across in a very different sort of document that I had been perusing earlier in the morning, the biennial “Comprehensive Social Conditions Survey” just out from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). That report listed the top 10 issues of current public concern in China, led by food price inflation (59.5 percent of respondents), health care availability and costs (42.1 percent) and the wealth gap (28 percent) ahead of a string of other bread-and-butter worries such as unemployment and housing prices. It was a Chinese version of the famous note pinned to a board in Bill Clinton’s campaign headquarters when he was running against George Bush Sr., “It’s the economy, stupid!” And nowhere on the list was there any mention of restrictions on freedom of expression, or the lack of democracy (although official corruption angers 29.3 percent of the population, according to the survey.)

When asked why this was so, Li Wei, one of the CASS researchers who had carried out the study, told the Christian Science Monitor, “Initially, he said, he and his colleagues had planned to ask about Internet censorship and the lack of freedom of expression. “But when we tested our questions in preparation for the survey, we found that villagers did not know what we were talking about,” he recalled. “They thought they had complete freedom because they don’t talk about politics, so they don’t have any problems.”

“That is not to say that we think freedom of expression is unimportant,” he added quickly. “But it is not important enough to enough people in China to make it part of our survey.” That is hardly the same thing as arguing, as Han appears to believe, that the Chinese people cannot be trusted with democracy until they are better educated and more civic minded. But it must offer the Chinese government a good deal of comfort.

Charter 08

Charter 08 is a pro-democracy manifesto released online in December 2008 that among other things: 1) calls for a new constitution that guarantees human rights and open elections of public officials; 2) brings greater freedoms and democracy in China; 3) getting rid of the subversion laws; and 4) seeks an end to one-party rule.

More than 10,000 people, including some of China’s top intellectuals signed it despite efforts by the government to block it and punish its authors but news black outs and Internet censorship kept most Chinese from becoming aware of it.

Modeled after Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, which was put together by scholars in that country in 1977, 12 years before the fall of Communism there, Charter 08 calls for a complete overhaul of the Chinese system and the introduction of true freedoms of speech and religion and independent courts. It states: “For China the path that leads out of our current predicament is to divest ourselves of the authoritarian notion of reliance on an “enlightened overlord” or an “honest official” and to instead move toward a system of liberties, democracy and the rule of law.”

Charter 08 also states: “Freedom is at the core of universal human values. Freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom of where to live and the freedoms to strike, to demonstrate and to protest, among others, are the forms that freedom takes. Without freedom China will always remain far from the civilized ideals.”

Charter 08 was sent to people from all walks of life through e-mail mainly by people who supported it sending it to their friends and contacts. One 30-something cosmetology students that signed it told the Washington Post, “I was afraid but I had already signed it hundreds of times in my heart...If me, a little frightened person signed it them maybe others will feel inspired.”

Xiao Qinag, an adjunct professor of journalism at Berkeley, told the Washington Post, “This is the first time that anyone other than the Communist Party has put in written form in a public documents a political vision for China. It’s dangerous to be associated with dissidents so in the past, other ordinary people have not signed such documents. But this time it was different. It has become a citizens movement.”

The effort was given a severe blow in December 2009, when Liu Xiaobo, one of the drafters of Charter 08, was given an 11-year prison sentence on subversion charges in what see a warning to anyone who dares to challenge the ruling regime.

See Separate Article Under Justice and Human Rights

Social Control Versus Economic Openness

Barbara Demick and David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The Communist Party has long wrestled with how to weigh the competing dictates of economic openness and social control...When there’s been a clash of those interests, Beijing almost always has come down on the side of control.”

Kenneth Lieberthal, a former Clinton administration official and senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, told the Los Angeles Times, “The Chinese are very mindful of the potential political repercussions of openness — they make no bones about it — and on the margins, their desire to maintain social stability will trump any other issue.”

Capitalism and Democracy in China

It was originally thought by some in the West that an emerging class of entrepreneurs and businessmen would push for democracy in China but by absorbing many of them into the system and the Communist Party and establishing links between the state and business so that it is difficulty to tell where the public sector leaves off and the private sector begins the Communist Party has been able to subdue any challenge the business community may have presented to its grip on power.

To get ahead businessmen generally need access to state bank loans and contacts with officials that control land, government contacts and bureaucratic authorizations they need. The same is true with students who want a successful career. Bruce Dickson, a China scholar at George Washington University and author of “Wealth Into Power The Communist Party’s Embrace of China’s Private Sector”, told the New York Times, “The party seems happy with that. They are not looking for die-hard ideologues. They want to co-opt people into the their system, And they’ve far more successful than people realize.”

Books: “Wealth Into Power: The Communist Party’s Embrace of China’s Private Sector” by Bruce Dickson, a China scholar at George Washington University; “The China Fantasy: Why Capitalism Will Not Bring Democracy to China” by James Mann.

Views on Democracy in China

One graduate student told The Guardian, “Chinese people don't hope to go the western way but hope for a powerful government to restore social justice.” [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, May 20, 2009]

According to the Asian Barometer study of political attitudes, the most comprehensive to date, came up with some surprising findings. In mainland China, 53.8 percent believed a democratic system was preferable. Asked how democratic it is now, on a scale of one to 10, the Chinese placed their nation at 7.22 — third in Asia and well ahead of Japan, the Philippines and South Korea. “Chinese political culture makes people understand democracy in a different way, and this gives the regime much manipulating space,” Dr. Tianjin Shi told The Guardian. [Ibid]

People in China complain bitterly about official corruption, inefficiency and brutality. But — as the government reminds them — multi-party elections do not guarantee good governance or stability. After decades of turmoil, many seem willing to settle for a quiet life and economic well being — at least for now. There's little sign that the current economic downturn is leading to widespread social unrest — still less open opposition to the government. [Ibid]

“Basically, I think they're doing a very good job,” one young woman told The Guardian. “China's so big, but it's not wealthy. The leadership have helped it develop fast. I looked at the G20 meeting in London and felt kind of proud of the government; foreign countries really hope that China can help...Maybe other people think oh, China, there's no freedom. But it's not easy to make everything perfect.” [Ibid]

Worries About Democracy in China

Democracy exists in Taiwan and is trying to establish itself in Hong Kong. Beijing worries that demands for more democracy in Hong Kong could spill over into the mainland.

Kerry Brown of Open Democracy wrote, “In interviewing people from various organizations and from very different perspectives, I was struck by a consistent undertone of worry about the prospect of a regime change (even a “color revolution”) along the lines of those in the post-Soviet states in the early 2000s - which culminated in the governing communist or reformed-communist parties being ejected from office. elections China's clear official aim is to ensure that it doesn't make the same mistake. But in a country undergoing rapid change, how much of the political course of events and outcome can the party still control?” [Source: Kerry Brown, Open Democracy, September 15, 2009]

“The leading party ideologues issued a booklet on 5 June 2009 called The Six “Why’s”, in an apparent effort to bolster the organization's ideological armoury in face of mounting social and intellectual challenges. The fifth item of this list was: “Why a western-style democratic parliamentary model is not going to work in China?” The framing is significant: these key party thinkers have worked out their reasons carefully for what they don't want to do. Their argument is that elections as they are conducted in the west would create instability; impede China's development at a critical juncture; and, in a complex society already stretched to the limits in terms of regional and class inequalities, risk the release of divisive political forces.” [Ibid]

Chinese Communist Party Stance on Democracy

In an article printed in April 2011 Global Times, veteran commentator Shan Renping repeated the CCP’s standard line that one-person-one-vote elections and "Western-style democratic politics" are not suitable for China. "China being a complicated and large country, a strong and forceful central government is absolutely necessary for unity and stability," Shan asserted. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, Jamestown Foundation, May 6, 2011]

In his address to the National People’s Congress in March 2011, parliamentary chief and Politburo Standing Committee member Wu Bangguo reiterated that the CCP would never adopt a "multi-party revolving-door system or other Western-style political models." "China’s national conditions strongly indicate that we not engage in multi-party rotations of political power, not engage in a diversity if guiding political ideologies...If we waver...the fruits of development that we have already achieved will be lost and the country could even fall into the abyss of civil strife," he said. Each year Wu gives a speech that strikes a similar theme.” [Source: New York Times]

Yu Keping, Proponent of Democracy within the Communist Party

Political scientist Yu Keping is one of China’s leading proponents of electoral democracy. Author of a prominent book called “Democracy Is a Good Thing”,” he has argued that some type of electoral democracy is central to China’s future. In addition to that he is considered an insider in the Chinese political establishment and is said to have the ear of President Hu Jintao. [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“Democracy is good not only for individuals or certain officials but also for the entire nation and for all the people of China,” Yu told Steven Hill, “Political democracy is the trend of history, and it is inevitable for all nations of the world to move toward democracy.” Yu then went on to talk about how, in his view, electoral democracy forces officials into the constructive practice of gaining the endorsement and support of the majority of people, a familiar Western theme, Hill said. He also believes that electoral democracy can act as a check against abuses of power by those officials, a particularly local concern given China’s notorious plague of corruption. While he talked of China having “unique characteristics” — often the Chinese way to tell Western scolds to bug off — he was unequivocal in saying that, for China, “democracy is not only a good thing but an essential one.” And, he pointed out, his view has been seconded by the top political leaders. [Ibid]

Hill wrote that while Yu’s “democratic theory for China sounds bold, his practice has been decidedly pragmatic and incremental. He is shrewd about the anti-democratic forces within the Communist Party — of which he is a prominent member — as well as the weight of China’s long authoritarian history. So he has promoted the idea of a “democracy cascade” in which elections gradually work their way up to the national level from successful local efforts. This strategy has led to some modestly impressive results.” [Ibid]

According to liberal intellectual Bao Tong, once a close aide to ousted party chief Zhao Ziyang but now disgraced and under virtual house arrest, the CCP’s renewed determination to spurn so-called Western norms would only exacerbate thecountry’s socio-political tensions. Bao, pointed out that values such as privatization, pluralistic political norms and the tripartite division of power were "good systems universally recognized by the international community." He added that only by adopting global democratic standards can the CCP "achieve real stability and real social harmony." [Source: Willy Lam, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, March 25, 2011]

Critics of Democracy in China

Chinese President Hu Jintao has called Western-style democracy a “blind alley.” In 2008 one Communist official said, “There aren’t that many countries with a multiparty system that are socially stable. Look at Thailand and Pakistan. These countries tend to be very unstable and troubled every time they hold elections. Foreigners respect China as we have maintained political stability for several decades.” the official then said the Communist party in China “will continue to lead for 20, 40 or 60 years.”

Li Pen, a leading figure in the National People’s Congress, told the China Daily, “Western-style elections are a game for the rich. They are affected by the resources and funding that a candidate can utilize. Those who manage to win elections are easily in the shoes their parties or sponsors.”

Pan Wei, a rising academic and ideological star in China who teaches at Beijing University and got a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley in 1996, is major critic of Western-style democracy. “Look at your own democracy, look at what your elections produced,” he told Steven Hill. “George Bush. In China, our president and premier, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiaboa, are highly educated men. Both are engineers, men of science. Professionals, highly competent. Your president is a frat boy with a silver spoon. How can you seriously argue that elections and democracy are superior?” [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“Democracy in China, at this particular time, would lead to chaos,” Pan says. He sees little electoral future in the near term, and believes that a better model for China is evident in places like Singapore and Hong Kong, which have developed successfully without robust representative democracy. Moreover, according to Pan, the premature introduction of democracy actually could undermine the rule of law and modernization, and he points to examples like Rwanda and Angola.” [Ibid]

In his address to the National People’s Congress in March 2011, parliamentary chief and Politburo Standing Committee member Wu Bangguo warned against the "seven nos": no adoption of Western values; no adoption of a "system of multiple parties holding office in rotation"; no pluralization of the guiding [state] dogma; no tripartite division of power among the executive, legislature and judiciary; no adoption of a bicameral legislature; no to a federal system, and no privatization. He added that to ensure China’s "correct political orientation," China’s institutions, Constitution and the laws must safeguard "the status of the CCP as the country’s leading core" [Source: Willy Lam, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, March 25, 2011]

Chinese-Style Meritocracy vs. Democracy

“But if Pan Wei doesn’t believe in democratic elections, what does he want?” Steven Hill wrote on his blog Truth Dig. “Sounding like an anachronistic noble from the court of a long-ago Chinese emperor, Pan advocates for a “Legalist” model that promotes the rule of law rather than elections...a Confucian-style meritocracy in which leaders are selected for their superior knowledge, skills and education. “No George Bushes would be selected through such a process,” he says, which sounds momentarily comforting. But if no one is elected, then who determines the rules of law” Who gets to decide, and how are they selected? These are basic philosophical questions, and Pan’s vision edges back into George Orwell territory, where the ruled eventually become the rulers only to take their turn at being a self-perpetuating dominator class.”[Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“More interesting, perhaps, is the vision promoted by Confucian-inspired intellectuals like Jiang Qing who have put forward an intriguing proposal for a tricameral legislature, with legislators in one chamber selected based on merit and in the others based on elections of some kind. One of these elected chambers may be reserved only for Communist Party members, the other for representatives elected by everyday Chinese.” [Ibid]

“Such a tricameral legislature, its proponents believe, would better ensure that political decisions were informed by a more educated and enlightened outlook, instead of the rank populism of Western-style elected factions. It’s intriguing to contemplate China evolving into some sort of innovative democratic experiment, combining tricameralism with all the high-tech features of professor Fishkin’s deliberative democracy methods to mold a new type of political accountability as well as separation of powers.” [Ibid]

“In contemplating these possibilities, Daniel Bell, a Canadian-born professor of political theory at Tsinghua University in Beijing, told Hill, China may be groping toward “a political model that works better than Western-style democracy.” He predicts that the Chinese Communist Party will one day be called the Chinese Confucian Party, perhaps governing via a hybrid meritocracy-democracy.” [Ibid]

Image Sources: 1, 2) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3, 5, 6) Carter Center; 4) Wellesley College

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012