LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN CHINA

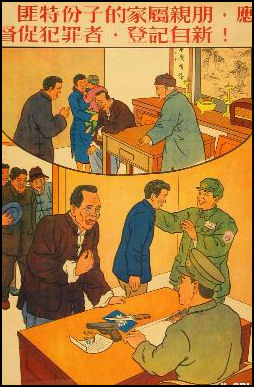

The Communist Party maintains control nationwide through a network of committees that oversee the administration of the country's local governments, universities, industries, schools and army units. There are tens of thousands of these committees and virtually every citizen has to answer to at least one. Local officials are usually named by senior officials and claimed by party committees.

The Communist Party maintains control nationwide through a network of committees that oversee the administration of the country's local governments, universities, industries, schools and army units. There are tens of thousands of these committees and virtually every citizen has to answer to at least one. Local officials are usually named by senior officials and claimed by party committees.

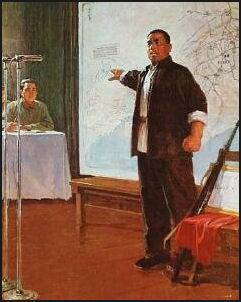

The system of governance in China is a combination of centralism and federalism, with a certain degree of autonomy granted to local governments, so central leaders are often unaware of what is really happening at the localities through normal bottom-up channels. Each province, city, town,prefecture and county in China is overseen by a parallel group of local leaders and Communist party officials. Village and towns may have elected chiefs and mayors but they generally have been nominated by the Communist Party and have little power anyway. Running the show are county governments, under the supervision of Beijing. They levy taxes, enforce one-child family planning policies and have jurisdictions over police that are authorized to crack down on religious and political activity. In cities and provinces the most powerful leaders are not the mayors and governors but are the party secretaries.

The Communist system in China depends on legions of police, local party and government officials to enforce Beijing’s policies and squash dissent. Local governments are supposed to be controlled directly by Beijing but in reality they are more often controlled by local party officials and are pretty much left up to their own devices in earning revenues and providing services. A lot of effort is put into collecting taxes, bribes and running state-companies to earn revenues.

George Yeo, Singapore’s foreign minister, wrote in Global Viewpoint, “During the Ming and Qing dynasty, there was rule that no high official could serve within 400 miles of his birthplace so he could not come under pressure to favor local interests...A few years ago the rule was reintroduced to the People’s Republic...In almost all cases today, the leader of Chinese provinces — neither the party secretary no governor — are from that province unless it is an autonomous region, in which case the No. 2 job goes to a local, but never the No. 1 job.”

Local governments have more authority, less oversight and more money than they did in the Mao era. Decisions and directives made in Beijing are not always carried out on the local level. This situation often results in corruption and an emphasis on development over environmental concerns. Many villagers feel they are screwed by local officials but believe that the central government is on their side and will right wrongs if the wrongs are brought to the central government's attention.

Local governments often ignore Beijing directives on issues such cleaning up the environmental and reigning in corruption. Often it seems that the central government is too timid to enforce their orders or that corruption culture is too embedded for anyone to do anything about it.

Municipal governments, which own all land in China, largely depend on sales of long-term property leases to fill their operating budgets. In many cases, private real estate companies collude with officials to clear and develop the land as quickly as possible.

Articles on GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CityMayors.com citymayors.com ; Administrative Divisions China.org,official Chinese government source china.org. ; China.org on Local People’s Congresses china.org.cn ; China.org on Township Enterprises www.china.org.cn

Township Government in China

The 30,000 townships are the lowest level of government. They are badly in debt because they are squeezed by counties for money and demands by 700 million rural people for schools, health care, road maintenance, irrigation works and other services. The tax base has shrunk as people have given up farming and moved to the cities.

In many villages, local chiefs have the most popular support. They are often prevented from holding office because they are not Communist Party members. There are often conflicts with township governments, which are appointed.

Local assemblies are called People’s Congresses. They are generally organized on the township level and have traditionally been filled by members appointed by the Communist Party. These days many of the positions are elected. Local people’s congresses have been described by Beijing as China’s “basic democratic system.”

In some places the number of government officials serving deputies in local people’s congresses has been reduced from as high as 80 percent to less than 50 percent.

See Democracy and Elections

Rural Local Government in China

County government often come under the jurisdiction of nearby city governments which in turn are under the province governments.

One of the biggest problems in rural China is that the bureaucracy and government that were created to help villagers has grown so large that they suck up resources that could help villagers. In the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 8) there were 8,000 people working the land for every official. In 1987 the ratio was 87 to 1. In 1998 it was 40 to 1 with the number of officials increasing rather than getting smaller.

In the town of Yi Xian in Hebei province the number of people running the local government increased from 5 in 1980 to 400 in 1997. To pay the salaries of all these people local people had to pay higher taxes and dish out 10 times as much for electricity as people in Beijing.

Local officials that are supposed to help rural people raise revenues for schools, hospitals, road building and police but also create new fees and taxes — for things like “setting up a township web site” and “stipends for the forest guards” that rob the rural people of what little they have. The initial phase of Deng reforms helped many rural people but after the emphasis switched to the cities taxes and education and health care costs rose while benefits and incomes shrunk. Rural areas get almost no support from wealthier areas.

The Chinese system rewards fraud and deception over concrete results. People are promoted on the basis of perceived progress. A popular expression to describe the status quo is “No lies, nothing accomplished.”

The Communist Party uses a bureaucracy called the “Letters and Visits” offices to address petitioners and complaints. In most cases their duties are to kick back complaints to local officials, keep statistics and tell the petitioners to go home. Petition System, See Protests

China has already hired 200,000 college graduates as village officials, believing more educated cadres will speed rural development.

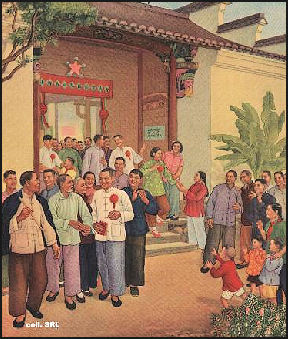

Village Governments

Village chiefs are often selected openly. But real power lies with the Party Secretary who is selected every three years during a closed-door session by local Communist Party members. The selection process is often an exercise in “guangxi” with the process manipulated by township party officials, the next level up from the village. In selection meetings there is little if any talk about platforms and policies. If the township official gives a speech praising every thing the existing party secretary has done, the local members echo these sentiments in their speeches and the party secretary is re-elected. [Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker ]

Village governments have a lot of power. They handle major land transactions and can break a 30-year lease for a nominal fee if a city developer wants some land. Village leaders must approve individual applications for government loans.

A typical village council is made up of 18 men and three women members of the Communist Party. Those with the most power are often respected the most by the others and skilled at dealing with higher up officials.

Party membership has traditionally been very selective. These days many urban people see few advantages with joining but in rural areas party members are often still regarded as the elite and membership can protect individual interests or provide opportunities that otherwise would be impossible. People in a village that have business interests often join the party to protect those interests.

Typical village meetings include self criticism sessions and reading of long jargon-filled passages from government documents.

Local Government Activities in China

Local governments have largely been responsible for the large investments that have stoked the economy to double digit growth. Their investments have also been responsible for rampant corruption, waste and environmental damage and practices such a real estate speculation and risky lending that may create a bubble and bring down the entire economy.

Cities and counties are not allowed to raise money through municipal bonds and the like so they often turn to real estate to make money. Often they use underhanded methods to get people off their land and sell the land rights for large profits. It is not unusual for the government to obtain the rights for $1 million and sell them three years alter to a developer for $30 million. By some estimates 40 to 60 percent of local government revenues are acquired this way.

Local officials are usually given a heads up when officials from Beijing make an inspection tour and usually have enough time to apply fresh coats of paint, coerce local people to be on their best behavior and fix whatever problems the Beijing officials have come to investigate. In 2007, when Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao came to check pollution produced by a dye plant on Lake Tai, the factory was given a makeover and canals around it were drained, dredged and filled with fresh water, with thousands of carp tossed in the water hours before Wen arrived and farmers positioned around the canals with fishing poles minutes before he arrived. .

Local officials are behind many illegal land sales. See Land Seizures, Agriculture

A lot of this activity has gone on with Beijing unable to control it. A scandal in Shanghai in 2006 has given Beijing an excuse to extend more control over local governments. See corruption.

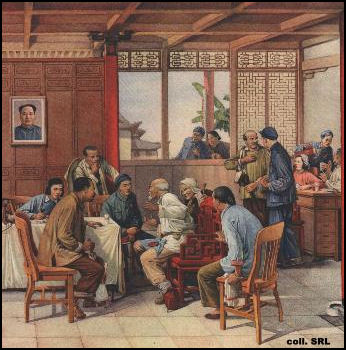

Neighborhood Committees in China

On a local level the Communist Party bureaucracy is made up of millions of neighborhood committees which have to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn are under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow guidelines laid out by the Central Chinese government. To keep their members in line, the local committees often use social pressure in the form of face-losing criticism.

Neighborhood committees in urban areas make sure the poor are fed, the elderly are looked after, petty crimes are brought to justice, one-child polices are adhered to, and family disputes — mostly between wives and mothers-in-laws — are settled. For the most part the streets in cities are safe, so safe in fact some residents bring their beds outdoors in the summer and sleep in the streets. [Source: William Ellis, National Geographic, March 1994]

A typical neighborhood committee controls three blocks and contains about 1,000 households. The leader and his or 30 or so "group leaders" are in charge of hanging party propaganda posters, leading weekly meetings of the local party cell, where new polices and rules are announced. Retired women often hold the job. They are sometimes called "bound feet detectives" because of their shuffling feet and busybody attitude. [Source: Wall Street Journal]

Neighborhoods are kept in line with “building bosses” and their helpers, “door watchers,” who keep an eye on what is going on in almost every house. Informers are everywhere. Communist-era proverb: "One Chinese watches a thousand; a thousand Chinese watch one."

Work Units in China

Most Chinese also have to answer to "community units" or "work units" (“dawei”) in their place of work, whether it be a factory, hospital or commune. These organizations exert control on almost every aspect of an individual's life: they give out ration cards, arrange day care, supply train tickets, choose which doctors and hospitals people must see, decide who gets housing, set salaries and recruit party members.

Work units are the main channel in Communist China for distributing social benefits and exerting social control. They keep files on their members and they often have to be consulted about personal matters such as travel, marriage, divorce, and birth control. The work units can pressure people by reducing wages and bonuses, by denying promotions and transfers, or by taking away the job completely.

In the old days, work units and neighborhood committees controlled marriages, divorces, pregnancies and birth control. To get married, a couple needed permission from a local board and a letter from an employer stating that a person is single. In some cases, employers would use their authority to solicit a bribe or demand some concession before the form was submitted. In most cases the employers provided the paper work but the couples felt inconvenienced and embarrassed asking for permission.

In the Mao era, people lived in assigned housing in state dormitories, communes and factory quarters and bought food and clothing with rationed coupons.

Power, Leadership and Reforms in Local Government in the 1980s

Vanity project for local officials The people's congresses at the provincial, city, and county levels each elected the heads of their respective government organizations. These included governors and deputy governors, mayors and deputy mayors, and heads and deputy heads of counties, districts, and towns. The people's congresses also had the right to recall these officials and to demand explanations for official actions. Specifically, any motion raised by a delegate and supported by three others obligated the corresponding government authorities to respond. Congresses at each level examined and approved budgets and the plans for the economic and social development of their respective administrative areas. They also maintained public order, protected public property, and safeguarded the rights of citizens of all nationalities. All deputies were to maintain close and responsive contacts with their various constituents.

“Before 1980 people's congresses at and above the county level did not have standing committees. These had been considered superfluous because the local congresses did not have a heavy workload and in any case could serve adequately as executive bodies for the local organs of power. The CCP's decision in 1978 to adopt the Four Modernizations as its official party line, however, produced a critical need for broad mass support and the means to mobilize that support for the varied activities of both party and state organs. In short, the new programs revealed the importance of responsive government. The CCP view was that the standing committees were better equipped than the local people's governments to address such functions as convening the people's congresses; keeping in touch with the grass roots and their deputies; supervising, inspecting, appointing, and removing local administrative and judicial personnel. The use of standing committees was seen as a more effective and rational way to supervise the activities of the local people's governments than requiring that local administrative authorities check and balance themselves. The proclaimed purpose of the standing committee system was to make local governments more responsible and more responsive to constituents.

“The establishment of the standing committees in effect also meant restoring the formal division of responsibilities between party and state authorities that had existed before 1966. The 1979 reform mandated that the party should not interfere with the administrative activities of local government organs and that its function should be confined to "political leadership" to ensure that the party's line was correctly followed and implemented. Provincial-level party secretaries, for instance, were no longer allowed to serve concurrently as provincial-level governors or deputy governors (chairmen or vice chairmen in autonomous regions, and mayors or deputy mayors in special municipalities), as they had been allowed to do during the Cultural Revolution. In this connection most officials who had held positions in the former provincial-level revolutionary committees were excluded from the new local people's governments. Some provincial-level officials who were purged during the Cultural Revolution were rehabilitated and returned to power.

“The local people's congresses and their standing committees were given the authority to pass local legislation and regulations under the Organic Law of the People's Courts of 1980. This authority was granted only at the level of provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities. Its purpose was to allow local congresses to accommodate the special circumstances and actual needs of their jurisdictions. This measure was billed as a "major reform" instituted because "a unified constitution and a set of uniform laws for the whole country have proved increasingly inadequate" in coping with differing "local features or cultural and economic conditions." On July 17, 1979, Renmin Ribao (People's Daily) observed: "To better enforce the constitution and state laws, we must bring them more in line with the concrete realities in various areas and empower these areas to approve local laws and regulations so that they can decide certain major issues with local conditions in mind." The law explicitly stated, however, that the scope of legislation must be within the limits of the State Constitution and policies of the state, and that locally enacted bills must be submitted "for the record" to the Standing Committee of the NPC and to the State Council, which, according to the 1982 State Constitution, can annul them if they are found to "contravene the Constitution, the statutes, or the administrative rules and regulations.”

Local Government Funding in China

The Economist reported: China’s local governments carry out over four-fifths of the country’s public spending, but pocket only half of the taxes. To help make up the difference, they rely on expropriating land from farmers and flogging it to bullish property developers. But as developers struggle, land sales are dwindling. As a result, local-government revenue is drying up. Popular resentment, meanwhile, is not. In Wukan, in the southern province of Guangdong, aggrieved villagers rose up in December against land-grabbing officials, chasing the local party chief away. [Source: The Economist, Feb 4, 2012]

By some estimates local government receive half their funding from real estate transactions. Typically they acquire farm land, put in some minimal infrastructure and sell the land to developers. During the reform years funding was cut off and authority became decentralized very quickly and governments had to scramble to come up with ways to make money. Real estate and land seizures proved to be a relatively easy way to make a lot of money.

The system encourages corruption and short-term thinking. Officials often only serve five year terms and there is an incentive for them to make money quickly before their term is up.

Zhu Rongji’s Tax Sharing System

Zhu, Rongji served as premier from 1998 until 2003. Before that he initiated and implemented a tax sharing system that gave the central government the lion's share of the country's taxation revenue. Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “Zhu's first move, after he was appointed as vice premier in charge of economic affairs in 1991, was to reform the taxation system so that the central government could have more money. After months of tough negotiations and bargaining with economically important provinces on how much they should contribute to the state coffers, Zhu eventually introduced the tax sharing system at the end of 1993.” The move was made in response to Deng Xiaoping economic reforms that gave regional governments greater say on local economic affairs, meaning central government had less and less revenues at its disposal. [Source: Wu Zhong, China Editor, Asia Times, June 22, 2011]

According to the tax sharing system as introduced by Zhu, the state would take a large proportion of the revenues and then give rebates to regions. However, the rebates were given back indirectly and not in a lump sum, rather taking the shape of subsidies on infrastructure, education, welfare and other sectors. This has given central government authorities much greater powers.

Under the system, each province would contribute a certain proportion of its taxation revenues to state coffers. While the proportion of contribution varies from province to province, on average the central government nominally could have a 60 percent-70 percent share of the nation's fiscal revenues while the rest would go to the regional governments. Afterwards, the central government would give back some funds to regional governments according to agreed proportions. The reform boosted the central government's revenues from 4.35 billion yuan in 1993 to 2.17 trillion yuan in 2003 when Zhu retired.

Criticism of Zhu Rongji’s Tax Sharing System

Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “Zhu apparently feels proud of the tax sharing system, seeing it as one of his great achievements” even though the system’s arrangement for tax rebates to the regions had become a hotbed of official corruption, as central government officials often took bribes before returning funds to the regions. [Source: Wu Zhong, China Editor, Asia Times, June 22, 2011]

In a speech at the Tsinghua School of Economics and Management in April 2011, the 83-year-old Zhu responded to assertions that China’s real estate problem stems from the tax sharing system by saying “This is bullshit!" To support his argument, Zhu gave a breakdown of revenues between central government and regional governments for 2010. This was the first time such figures have been made public. According to him, China's fiscal revenue totaled 8.3 trillion yuan (US$1.28 trillion) last year, of which 4 trillion yuan directly went to regional government coffers. Then, following the tax sharing system, the central government gave the regional governments another 3.3 trillion yuan from its own share as rebates. "As a result, the regions got 7.3 trillion yuan in total. Still not enough? Still poor? Now regional governments have plenty of money," Zhu said.

Zhu angrily lashed out at a book that is still officially banned in China, Zhongguo Nongmin Diaocha (An Investigation of China's Peasantry) by the husband-and-wife authors Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao. The book blamed the tax sharing system for hardship in rural areas, arguing that because of the system local governments lacked funds to support compulsory education, family planning and social security and welfare. In response Xhu said, "Tax rebates are not done well. Regions have to curry favor with relevant ministries to beg for their rebates. There are shortcomings in the tax sharing system, which however I am not entirely responsible for. For, I had said long ago that the taxation reform was far from over and should be deepened."

Land Seizures and Local Government Revenues

About 40 percent of local government revenue came from land sales in 2010, year, according to China Real Estate Information Corp., a property data and consulting firm.Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The land issue looms large in the countryside. Local governments earned $470 billion from land deals in 2010, up from $70 million in 1989, according to the Ministry of Land and Resources, and farmers — who lease their land rather than own it under the communist system — have scant protection if local officials want to give the leases to real estate developers who will pay more. Compensation is often inadequate. Chinese laws designed to protect farmland by requiring permission from the State Council — in effect, the country's Cabinet — for transfers are widely ignored by local officials. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2011]

Yu Jianrong, a professor and expert on rural issues at the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimates that local officials have seized about 16.6 million acres of rural land (more than the entire state of West Virginia) since 1990, depriving farmers of about two trillion yuan ($314 billion) due to the discrepancy between the compensation they receive and the land's real market value. [Source: Jeremy Page and Brian Spegele, Wall Street Journal, December 15, 2011]

Jeremy Page and Brian Spegele wrote in the Wall Street Journal:In 2010 alone, China's local governments raised 2.9 trillion yuan from land sales. And the National Audit Office estimates that 23 percent of local government debt, which it put at 10.7 trillion yuan in June, depends on land sales for repayment.

TVEs

China’s drive toward modernization and economic growth after 1978 was propelled forward in many respects by the so-called township and villages enterprises (TVEs) — local government bodies that were given the freedom to establish businesses and enter into the emerging market economy. Usually small factories in rural areas, they have absorbed millions of farmers and been a powerful engine for growth.

On the negative side TVEs have encouraged developers and officials to form alliances and throw peasants off their land. Many of China’s problems — the seizure of land from peasants, workers forced to work under sweatshop conditions and factories spewing out pollutants — have their roots in local corruption and abuses by local officials which in turn have their roots in the TVEs.

The historian Francis Fukuyama wrote: “The TVEs were enormously successful, and many today have become extraordinarily rich and powerful. In cahoots with private developers and companies, it is they who are producing the “satanic mills” of early industrial England...The central government, by all accounts, would like to crack down on these local government bodies but finds itself unable to do so. It both lacks the capacity to do this and depends on local governments and the private sector to produce jobs and revenues.”

“The Chinese Communist Party understands that it is riding a tiger. Each year there are several thousand violent incidents of social unrest, each one contained and suppressed by state authorities, who nevertheless cannot seem to get at the underlying source of the unrest,” Fukuyama wrote. China “may be the first country where demand for accountable government is driven primarily by concerns over a poisoned environment. But it will come about only when popular demand for some form of downward accountability on the part of local governments and businesses is supported by a central government strong enough to force local elites to obey the country’s own rules.”

Local Bosses and Arrogant Officials in China

Under the Communist system cities, towns, counties and communities are often ruled by local bigwigs, who can be party officials, military leaders, mayors or powerful businessmen. The leaders often got where they are because they worked out a system of running things. These days businessmen are often the ones who run things because they are the most effective at generating revenues.

Perhaps no group here is more vilified and mistrusted than China’s local officials, who shoulder much of the blame for corruption within the Communist Party. The party constantly vows to rein them in; in October, President Hu Jintao said a clean party was a matter of life and death.In many places local officials answer to no one, and that anyone who dares challenge them is punished.

Many of the local bosses wield power like gangsters. The activist lawyer Gao Zhisheng wrote on the Internet in 2005, “Most officials in China are basically Mafia bosses who use extreme barbaric methods to terrorize people and keep them from using the law to protect their rights.” A survey of 3,376 Chinese conducted by the magazine Insight China in 2009 found that prostitutes were considered more trustworthy than government officials.

It is not uncommon to find a local Communist Party Secretary, whose salary is about $450 a month, living in a five-story mansion, own several other large houses and have investments in other businesses and property. See Corruption

The party bosses owe much of their power to the Deng reforms, which gave them broad powers over bank lending, taxes, regulations and land use. Bosses have been evaluated primarily the ability for make the economy grow in their regions and are given a lot of power to achieve these goals, including near complete control of the police and courts in their jurisdictions. This has led to collusion between business interests and neglect of the environment.

Well-connected people often act like they are above the law and get off with light sentences when they are arrested. In December 2003, the wife of an important official in Heilongjiang Province was given a suspended sentence for a crime that many though was blatant murder. The woman had been driving her BMW when it was scratched by the cart of a peasant farmer. The woman got out of her car, yelled at a group of peasants, got back into her car and the plowed into the peasants, killing one and injuring 12 others. Internet chat rooms were filled with angry comments about the incident. A new investigation was opened. The official whose wife was involved in he incident was later removed from his post.

In May 2005, a provincial legislator in Liaonong province was sentenced to death for murdering a pedestrian in a drunken rage by running him down with his sport utility vehicle two months earlier. The victim, a 55-year-old man, had apparently brushed the rear view mirror of the legislator’s car and tried to run away.

See Bureaucrats. Corruption

Local Governments Ruled by Thugs

“I spent the month of August 2009 travelling around China and looking at the state of democracy (in the sense of “village elections”), the rule of law, and civil society, “Kerry Brown of Open Democracy wrote. “It was a sobering experience full of disturbing revelations... I was startled by how many village-level areas were lawless, ruled by different groups - and largely out of the reach of the central authorities.” [Source: Kerry Brown, Open Democracy, September 15, 2009]

“In China's northeast, quasi-mafia groups have made entire rural areas their fiefdoms, which they run according to their extensive business interests. In the southeast province of Fujian, similar elite economic groups have established control of villages via local representatives who ruthlessly pursue the groups' private interests with no regard for broader social goals. In the central provinces of Hunan, Henan and Hebei, most evidence I saw showed a clear battle between party operatives and other increasingly powerful groups (from specific clans in one area, to economic or ethnic or social groups in another)...In large swathes of the Chinese countryside, there seem to be as many different rules as there are groups. The strongest are taking what they want.”

“The problem of this messy and fearful social landscape is reinforced by the party's domination of the political landscape - and the pitilessness with which it has exercised this domination. It remains the case that on many key issues, no voice except that sanctioned by the party can be regarded as legitimate. But in many areas, it is clear that a by-product of this chloroform - namely, the attempt to be all things to all people, to accommodate (and thus internally defuse) all sorts of opinions and attitudes amongst party members - has had the opposite effect to that intended: it has created an entity with potentially dangerous internal divisions.”

“Several academics I talked offered sharp insights into the party's and government's current predicament. One as good as said that democracy at the village level had made things worse. Another complained that lawyers were now becoming a huge enemy within, challenging the government and starting to articulate demands that were becoming more and more political in their complexion.”

“Behind all of this is the immense security apparatus that the CCP now relies on for so much for its authority in “difficult” areas. A recent report estimated that China had no less than 1 million secret-intelligence operatives. How are these tasked and funded; who they are answerable to; how is their effectiveness assessed? These are not simple questions to answer. But somewhere, on someone's budget-sheet, is the costs of a huge amount of people assigned to use government money on “dealing with subversive and terrorist activity”. It would be fascinating to know just what this amounts to in financial cost alone.”

“I am more disheartened than I was even a month ago by how things are in China. The central state seems less effective and in control in many areas than I had thought. Its responses to potential threats are becoming more and more predictable - imprisoning, intimidating, coercing... Even institutionally, the Communist Party has created a monstrous problem - a massive, largely unaccountable, avaricious and often ineffective security apparatus full of individuals with no legal accountability, who most of the time - at both national and provincial levels - act to preserve their own narrow interests, and who when threatened expertly play a “protecting-national-stability-and-interest” card.” [Kerry Brown is an associate fellow on the Asia program, Chatham House. He is the author of “Struggling Giant: China in the 21st Century” (2007), “The Rise of the Dragon: Inward and Outward Investment in China in the Reform Period 1978-2007" (2008) and “Friends and Enemies: The Past, Present and Future of the Communist Party of China” (2009).]

Chinese Regions Defying the National Government

Wu Zhong wrote in the Asian Times, “Senior officials from the Chinese Communist Party may often have differing views on major issues, but it is rare for them to openly talk about their differences, and even rarer for regional officials to make public comments in open defiance of the central party line.” [Source: Wu Zhong, Asian Times November 26, 2008]

“This is why comments in November 2008 by Wang Yang, the party chief of Guangdong province in south China, have made shockwaves. He rebutted Premier Wen Jiabao's instructions on how to help small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) overcome difficulties as part of Beijing's efforts to ride out the global financial crisis.”

“Wang Yang's outburst immediately sparked speculation about possible power struggles in the party, but it is also a good, albeit rare, example of the regional realities in China. Provinces have their own concerns and interests quite different from those at the power center, and for a provincial leader it is often more important to safeguard local interests than to tow Beijing's line.”

One village chief told the New York Times, "Sometimes, when we don’t like a decision we procrastinate on purpose and we won't execute it. For example the government pushed hard to build a fertilizer plant and asked our village to raise 100,000 yuan [$12,000]. We didn’t like it, and finally our procrastination trashed the deal."

In August 2005, more than 10,000 protestors rioted in the city of Daye in Hubei Province over a plan by the larger city of Huangshi to annex it. Windows were broken. Dogs were brought into to control the crowd.

Perks for Bureaucrats and Officials in China

By some estimates a quarter of government revenues goes to pay for the maintenance of China’s 6 million officials at all levels. Expenses include banquets, chauffeured cars, travel junkets and trophy buildings and public works projects. More than $20 billion is spent on entertainment for Chinese officials alone. One Communist party member reportedly bet $25,000 on a single hand of baccarat at a casino in Macau.

Status among officials is often defined by large, chauffeur-driven, foreign-brand cars with tinted windows. The price tag for such perks is quite high. The total cost of buying official cars in 2004 was $6.1 billion, an increase of more than 20 percent from the previous year. When fuel consumption, maintenance and the salary for drivers is added in the total cost reaches $36.7 billion a year, more than China’s official $35 billion military budget.

Efforts to curtail the practice have gone nowhere. By some counts one in four vehicles on the road in Beijing are official cars. Audi 100s and Buicks are favored among high-level officials. Many are outfit with a beeping siren that allows them to force their way through traffic jams. Rules passed in 1994 to deny cars to officials below the vice minister level have been widely ignored.

In one county in Henan Province, the government could only afford to pay teachers 70 percent of their meager salary yet could spend $62,000 for 36 cars for officials. Particularly irksome to ordinary people is the fact that officials often use the cars for private matter such as taking their kids to school and driving to expensive restaurants for meals.

Perhaps even more outrageous that the cars are some of the “fubai lou”—“corruption buildings.” One in Tianjin that cost $40 million has professional quality billiards and snooker table, and indoor swimming pool, a golf practice center and ping pong tables surrounded by spectator seating. The city of Taian in Shandong Province built an $80 million white palace at the foot of Mt. Tai with a music-activated fountain that shoots water 100 meters into the air and is adorned with 2480 lights. The money to build the projects often comes from land grabs or taxes.

Decline of Neighborhood Committees and Work Units in China

Neighborhood committees and work units no longer exert the control on people's lived they once did. The process began in the in the 1980s with the rapid collapse of rural communes when farmers were given land and decision-making. Next the work units began collapsing as state-owned industries went bankrupt and stop functioning.

Work units and neighborhood committees don't control marriages, travel. divorces, pregnancies and birth control like they used to although they are still on the front line in the battle to uphold teh one-child policy.

There are still an estimated 500,000 neighborhood committee cadres. The leaders are paid around $250 a month. These days their duties include assisting the unemployed find jobs, organizing anti-crime efforts, keeping track of childbearing women, and helping married couples stay together. From time to time, the leader are called on to do things like count Falun Gong members.

There is now some discussion about making the neighborhood committees small welfare agencies and hiring college graduates instead of retired women.

See State White-Collar Workers in the Mid-2000s, Labor, Economics

Shenzhen Reforms in China

By 2011 the mayor of Shenzhen is supposed to be elected by the municipal people's congress, or local parliament. A policy will also be introduced to assure that elections will field more local candidates than available seats. This mandate will apply to the selection of the heads of Shenzhen's districts by the respective people's congresses. Some Chinese academics have said if the experiment in Shenzhen succeeds, the reforms will be instituted nationwide.[Source: Sun Wukong, Asia Times, July 31, 2008]

Sun Wukong wrote in the Asia Times, “At present, the mayor of Shenzhen - and likewise in all other cities - is already elected by the municipal people's congress. But, as it stands, such democracy is only a word: congressional deputies have no choice but to vote for the only candidate recommended by the Shenzhen municipal committee of the CCP. The practice has become so commonplace that many deputies sarcastically call themselves “hand-raising robots”. After all, in the one candidate, one seat elections the only option is to endorse whomever is presented.”

“The introduction of additional candidates means the next Shenzhen mayor, although still likely to be nominated by the local party committee, must compete with other candidates. Clearly, this will force all mayoral hopefuls to elucidate and differentiate their respective platforms in order to win votes. This is an important first step toward political democratization, but there is a long journey ahead. Candidates will likely still be nominated by the party and there is no sign that entry into the contest election will be free. Also, many of the deputies in Shenzhen municipal people's congress were not freely elected to their positions and may owe debts of patronage.”

Separation of Powers in Shenzhen

“The most prominent and ambitious item in the Shenzhen reforms,” Stephanie Wang wrote in the Asia Times, “is reform of the administrative system, which will divide the municipal government departments into three categories, namely, decision-making, execution and supervision. The reform has been wildly tagged as an experiment in “separation of powers”, something new and definitely challenging for the Middle Kingdom.” [Source: Stephanie Wang, Asia Times, June 13, 2009]

“Beijing News said the Shenzhen municipal government had a three-year plan for a step-by-step “separation of powers”, with the main idea having a single mayor and a deputy. Under the mayor, there will be “policymaking commissions” under which there are “policy execution” departments. The existing Supervision Bureau and Audit Bureau will be incorporated into a single body, which will take over all supervision functions now exercised by various departments.”

“But a cloud of suspicion still hangs over the city's reform plan. Qiu Feng, a well-known liberal scholar, has pointed out no matter how the structure is designed, the mayor will always be above the three branches. Then comes the tough question - who will oversee the mayor? The reform can also be interpreted as giving the administration all legislative, executive and judicial powers.”

“Shenzhen has drawn a lot of its ideas from Hong Kong, for instance, from the Hong Kong Independent Commission Against Corruption and Audit Commission. Hong Kong and Singapore are executive-led models, meaning the governments are very powerful. But both governments are also known for their integrity and efficiency. The secret of their success lies in the design of the separation of powers.”

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ except Vanity project (Julie Chao) and official (Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012