CHINESE BUREAUCRACY

a chop is used instead

of signature In ChinaThe powerful State Council is China’s highest administrative body. It makes proposals to the Standing Committee of the Politburo and takes care of the day-to-day operations of the country. It is a huge bureaucracy controlled by the Communist Party and headed by the Prime Minister. Through its hierarchy of ministries and agencies, the State Council carries out the directives of the Politburo. Among the agencies are the Ministry of Truth and a Department of Propaganda.

The bureaucracy is led by the party elite. Participation is limited to members of the Communist Party. The Central Party School is the top training ground for Communist Party bureaucrats. All the top leaders attended it.

During the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618 — 907), there was one official for every 2,927 people. During the more recent Qin Dynasty (1644 — 1911), there was one official for every 299 people. But in modern China, there are up to 50 million officials, amounting to about one official for every 27 people. Its bureaucracy certainly cannot complain about being understaffed.

John Lee wrote in Newsweek, “While modern China is the most overgoverned land in Asia, it is also one of the worst governed. Even as China has decentralized and officials have multiplied, the country is not building the institutions needed for better transparency and accountability. CCP’s influence over courts, bureaucracies, media, research institutions, and state-controlled enterprises are well known. It’s difficult to make CCP’s local officials accountable when Beijing relies on them to maintain the party’s hold on power in far-flung places.

There are roughly 300 million government employees in China.In recent years the central government has vowed to shrink the bloated bureaucracy. They have laid off some people and reduced salaries yet many people continues draw substantial salaries at the taxpayers expense.

A great deal of time is taken up by sitting through lengthy meetings which accomplish little and sifting through lengthy documents and paperwork that are largely waste time. In 2007, the State Council set limits on the lengths of official meetings, speeches and documents.The bureaucracy is slowly reforming and becoming more accountable. A health minister was fired for mistakes made during the SARS crisis in 2003. This was seen as a sign that leading bureaucrats were going to be held accountable for their actions.

Articles on GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Wikipedia article on the Government of China Wikipedia ; Chinese Government site on the Chinese Government english.gov.cn ; Carter Center China Program cartercenter.org ; Official Chinese government source on Social Security china.org ;

Central Organization Department and the Communist Party Bureaucracy

The Chinese government elite, which includes about 2,800 people at or above director or vice minister level, in the government and military, is intensely loyal, Kerry Brown said.

The Central Organization Department is the party's vast and opaque human resources agency. Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “It has no public phone number, and there is no sign on the huge building it occupies near Tiananmen Square. Guardian of the party's personnel files, the department handles key personnel decisions not only in the government bureaucracy but also in business, media, the judiciary and even academia. Its deliberations are all secret. [Source: By Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, July 25, 2010]

If such a body existed in the United States, Richard McGregor wrote in his book “The Party” it "would oversee the appointment of the entire US cabinet, state governors and their deputies, the mayors of major cities, the heads of all federal regulatory agencies, the chief executives of GE, Exxon-Mobil, Wal-Mart and about fifty of the remaining largest US companies, the justices of the Supreme Court, the editors of the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the bosses of the TV networks and cable stations, the presidents of Yale and Harvard and other big universities, and the heads of think-tanks like the Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation." [Ibid]

Economic policy and other important policies are still largely shaped by the government’s central planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission. Many think that policy could be shaped more effectively and efficiently if the agency was stripped of some of its responsibilities,

Foreign policy is ultimately crafted not by the foreign ministry but the party's Central Leading Group on Foreign Affairs, and that military matters are decided not by the defense ministry but by the party's Central Military Commission. These and other party groups meet in secret.

In “The Party” McGregor described the existence of a network of special telephones known as "red machines," which sit on the desks of the party's most important members. Connected to a closed and encrypted communications system, they are China's version of the "vertushka" telephones that once formed an umbilical cord of party power across the vast expanse of the Soviet empire. All governments have their own secure communications systems. But China's network links not just ministers and senior party apparatchiks but also the chief executives of the biggest state-owned companies — businessmen who, to outside eyes, look like exemplars of China's post-communist capitalism.

At the National People’s Congress in 2008, China announced plans to streamline its massive bureaucracy by merging some large ministries into “super-ministries” covering areas such as transportation, social services, environmental protection, housing and construction. but not energy. The idea was that with increased power, streamlining, and separation of regulation and enforcement from policy the super ministries would make it harder for provincial governments to ignore rules set in Beijing.

Local Administration in China

Governmental institutions below the central level are regulated by the provisions of the State Constitution of 1982. These provisions are intended to streamline the local state institutions and make them more efficient and more responsive to grass-roots needs; to stimulate local initiative and creativity; to restore prestige to the local authorities that had been seriously diminished during the Cultural Revolution; and to aid local officials in their efforts to organize and mobilize the masses. As with other major reforms undertaken after 1978, the principal motivation for the provisions was to provide better support for the ongoing modernization program. [Ibid]

“The state institutions below the national level were local people's congresses — the NPC's local counterparts — whose functions and powers were exercised by their standing committees at and above the county level when the congresses were not in session. The standing committee was composed of a chairman, vice chairmen, and members. The people's congresses also had permanent committees that became involved in governmental policy affecting their areas and their standing committees, and the people's congresses held meetings every other month to supervise provincial-level government activities. Peng Zhen described the relationship between the NPC Standing Committee and the standing committees at lower levels as "one of liaison, not of leadership." Further, he stressed that the institution of standing committees was aimed at transferring power to lower levels so as to tap the initiative of the localities for the modernization drive. [Ibid]

“The administrative arm of these people's congresses was the local people's government. Its local organs were established at three levels: the provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities; autonomous prefectures, counties, autonomous counties (called banners in Nei Monggol Autonomous Region (Inner Mongolia)), cities, and municipal districts; and, at the base of the administrative hierarchy, administrative towns (xiang). The administrative towns replaced people's communes as the basic level of administration. [Ibid]

“Reform programs have brought the devolution of considerable decision-making authority to the provincial and lower levels. Nevertheless, because of the continued predominance of the fundamental principle of democratic centralism, which is at the base of China's State Constitution, these lower levels are always vulnerable to changes in direction and decisions originated at the central level of government. In this respect, all local organs are essentially extensions of central government authorities and thus are responsible to the "unified leadership" of the central organs. [Ibid]

Chinese Communist Bureaucrats and Officials

The traditional Communist bureaucracy operates under a command system of specified ranks called “nomenklatura” in which everyone knew his place, his role, and what he was supposed to do, think and say. Bureaucrats have traditionally been resistant to changes because in many cases change would make them obsolete and unnecessary. Common terms used to describe Communist members included “appartchik”, a petty bureaucrat; “cadre”, a group or a member of a group of Communist loyalists; and “commissar”, a personnel officer responsible for morale and discipline.

On the bureaucratic elite of is the Communist Party, George Yeo, Singapore’s foreign minister, wrote in Global Viewpoint, “When working properly the mandarinate is meritocractic and imbued with a deep sense of responsible of the whole country.” Yeo told Global Viewpoint, “Although politics in China will change radically as the country urbanizes the core principals of a bureaucratic elite holding the entire country together is not likely to change. Too many state functions affecting the well-being of the country as whole require central coordination, In its historical memory, a China divided always means chaos.

Describing a typical Communist official, Rudolph Cheleminski wrote in Smithsonian, "Bright, confident, well-spoken but still bearing that indefinable air of defensiveness when...encountering Westerners. Milling, ironical, circumlocuting with practiced rhetorical skill, prodding, rebutting when there was no call for rebuttal, answering questions with questions, he fenced more than he participated in an interview."

The work load of some senior officials is quite high. They have a responsibility to keep friends, colleagues, and investors entertained in a punishing round of restaurants, karaoke bars and massage parlors. [Source: John Sexton, China.org.con, May 28, 2010]

Chinese Cadre System

Communist officials are known as cadres. A cadre is defined by the Oxford University Press Dictionary as “a small group of people trained for a particular purpose or profession.” High-level officials are sometimes referred to as mandarins, a term used to describe elite bureaucrats in imperial times. Senior cadres remain overwhelmingly male, but there is now a compulsory retirement age and even (very low) quotas for women.

According to the Library of Congress: The party and government cadre (ganbu) system is the rough equivalent of the civil service system in many other countries, The term cadre refers to a public official holding a responsible or managerial position, usually full time, in party and government. A cadre may or may not be a member of the CCP, although a person in a sensitive position would almost certainly be a party member.[Source: Library of Congress]

Overhaul of the Chinese Cadre System in the 1980s

The Chinese cadre system went through a massive overhaul in the 1980s that reduced its size, made it more efficient and transformed it into the one of the primary instruments of national policy. In an August 1980 speech, "On the Reform of the Party and State Leadership System," Deng Xiaoping declared that power was overcentralized and concentrated in the hands of individuals who acted arbitrarily, following patriarchal methods in carrying out their duties. Deng meant that the bureaucracy operated without the benefit of regularized and institutionalized procedures, and he recommended corrective measures such as abolishing the bureaucratic practice of life tenure for leading positions. In 1981 Deng proposed that a younger, better educated leadership corps be recruited from among cadres in their forties and fifties who had trained at colleges or technical secondary schools. [Source: Library of Congress]

“The theme of "streamlining and rejuvenating" the bureaucracy was taken up by Zhao Ziyang in early 1980 when he announced a major overhaul of the government. The number of vice premiers was reduced from 13 to 2, State Council agencies were cut by almost half, and the number of ministers and vice ministers was reduced from 505 to 167. The new appointees were younger and better educated than their predecessors. In January 1982 Deng called for a "revolution" in the bureaucracy, starting with its top levels. At that time, Deng envisioned reducing the size of the government bureaucracy by onequarter over a two-year period. By retiring veteran cadres, the way could be opened for promoting younger, professionally competent cadres to positions of authority and thereby providing the effective leadership needed for China's modernization. In May 1982 the Central Committee reorganized and streamlined its internal structure by cutting staff in its 30 component departments by 17.3 percent. Subordinate bureaus were reduced by 11 percent. Almost half of the CCP Central Committee elected in September 1982 were new members, and 83 percent of the alternate members were newly elected. [Ibid]

“Reorganization of the provincial-level party and government structures took place between late 1982 and May 1983. During this period, almost one-third of the provincial-level party first secretaries and all but three of the governors were replaced, most of them moving into advisory positions. Almost two-thirds of provincial-level leaders in 1986 were college or university educated. During 1983 and 1984, these reforms reached the prefectural, county, municipal, and town levels, reportedly resulting in a reduction in staff of 36 percent and an elevation in the percentage of college educated leaders to 44 percent. [Ibid]

“Simultaneous with restructuring and rejuvenating the bureaucracy, a drive was begun to improve the party's working style and consolidate party organizations. The Second Plenum of the Twelfth Central Committee, held in October 1983, initiated such a program for the years 1984-86. Some 388,000 party members participated in the first stage of party rectification. These included high- and middle-ranking cadres in 159 leading organs in the central departments, provinces, autonomous regions, special municipalities, and PLA. This phase of the campaign lasted over a year and was accompanied by the recruitment of 340,000 technicians and 32,000 college and university graduates and postgraduates into the CCP. In addition, a campaign was launched to ferret out residual leftist influence from the Cultural Revolution period, factionalism, and corruption. Discipline inspection committees were reinstituted. Three kinds of party members were singled out as special targets: followers of the Gang of Four or of Lin Biao, factionalists, and persons who "beat, smashed, and looted" during the Cultural Revolution. These members were to be expelled from the party. Lesser offenders requiring correction included party members with bureaucratic or patriarchal attitudes, those seeking personal power and position, and those inept or lazy in their work. [Ibid]

“The principal objective of the reform leadership was to establish a system of steady, predictable rule through the creation of a professional bureaucracy. An important aspect of the program was personnel reform. Guidelines were issued that set age limits for key offices. A limit of sixty-five years of age was imposed for government ministers, sixty for vice ministers and department chiefs, and, for all other officials, sixty for men and fifty-five for women. The effect of this key reform was to bring to an end the lifetime tenure system that had been fundamental to China's bureaucracy since 1949. There was the additional stipulation that officeholders in the reconstructed bureaucracy be qualified both politically and professionally, that is, be both "red" and "expert." The reorganization and streamlining of provincial-level party and government bureaucracies followed the same procedures, including reducing the staff sizes and number of offices, lowering the average age, and raising the educational requirements for candidates for provincial-level leadership. These changes were considered essential to providing for a "third echelon" of leaders. This group could serve in positions of some authority, where they could be trained, observed, and evaluated as to their suitability for increased responsibility. Below the central level, the chosen age for leaders at the level of provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities was fifty-five; at the county level, between thirty and fifty years. [Ibid]

The second stage of party rectification, having the same goals as the first stage, began in the fall of 1984 and encompassed prefectural and county-level units. This stage involved some 13.5 million cadres, or about one-third of the party's membership. The third and final stage of the three-year party rectification campaign was launched in November 1985 and targeted party units "below the county level." This stage encompassed almost 20 million party members, about half the total membership of the party. These members belonged to the more than 1 million party branches throughout the rural areas. The campaign worked from the higher to the lower level organizations and proceeded methodically "in stages and groups." But while party pronouncements at previous stages of the rectification had complained about the perfunctory manner in which the campaigns were being managed, at this final stage the central authorities displayed notable leniency and caution. They feared that extensive restructuring and rebuilding of the local leadership had the potential to disrupt both production and social order. Even in cases of embezzlement, graft, and other "unhealthy practices," the party counseled circumspection and the employment of moderate measures. Subjecting local leaders to condemnation at mass meetings, a practice prevalent during the Cultural Revolution, was strictly forbidden. [Ibid]

Bureaucrat Behavior in China

The Communist bureaucracy functions under many of the same principals of the old imperial bureaucracy, namely operating under a rigid hierarchy and acting to serve its own self interests and unresponsive to the needs of the people it supposed to serve.

The bureaucracy in China has been described as a “multiplicity of competing ministries and bureaucratic levels” defined by “the constant distractions of interdepartmental buck-passing and turf wars.”

A meritocracy it isn’t. Local officials are often promoted even though they have miserable records. They often advance using “framing, fawning, stealing and sneaking” and seeking their self interest.

Under ancient Chinese system of patronage, which is still followed to some degree today, officials received appointments from above in return for remuneration from below. And people who collected taxes and other payments kept some for themselves and passed on the rest to their superiors.

Bureaucrats have traditionally gone through great lengths to make sure they didn’t make any mistakes or anger a superior. High-level officials make the decisions behind the scenes and mid-level cadres carry out the decisions. One environmentalist told The New Yorker, “In all the bureaus...everybody is just thinking about how to say the right thing to please his boss. Instead of real information, there’s a lot fake information...Finally, everyone just cares about what he can get for himself. The goal becomes personal survival.”

Chinese government official, according to the Times of London, fear being sacked or jailed if they said anything deemed inappropriate to U.S. officials. One civil servant told the Times, “The security people will study these documents word by word, After all, that’s their job, They already make a record of anyone who meets with a U.S. diplomat and so they will be able to put together the date in the cable with the date of the meeting and from the content can easily identify anyone.” One official was sent to jail for 10 years in 1992 for revealing in advance the text of a speed by President Jiang Zemin to a Hong Kong reporters.

Many low-level Communist officials drive black Volkswagen Santanas. Often they are among the worst drivers on the roads, in some cases producing gridlock traffic jams with their impatience. High-level officials like to travel around China with an entourage. In 2009, state media warned that growing competition for government jobs appeared to have encouraged cheating in the civil service entrance exam, with about 1,000 cheaters caught over a four month period.

Wang Yang, a Communist Party leader of Guangdong Province and a member of the Politburo, is major proponent of what he calls “mind liberation” — the process of opening of the bureaucracy to new ways of thinking.

Dead Souls That Never Show Up for Work

A nationwide campaign launched by Beijing in 2005 to check and get rid of "dead souls" in the civil service — workers who collect salaries without showing up for work — discovered 263 of them in Sinan, a very poor county in Guizhou province. They took more than 4 million yuan (US$606,000) out of the local government's 98 million yuan annual fiscal revenue. In other places, ex-officials convicted of corruption and imprisoned were found to be being paid their salaries, along with the salaries of dead bureaucrats. The campaign lasted for two years, and by 2007 many regions were able to report "success". For example, Shandong and Hubei provinces announced they had got rid of more than 10,000 and 7,000 "dead souls". [Source:Wu Zhong, Asia Times, February 17, 2011]

The case of Jiang Jingxiang in Longyan city — a civil servant in Fujian province who was paid a monthly salary for nine years without turning up to work for a single day — was exposed in 2011. The disclosure cast doubt on the success of the 2005 campaign. And the Chinese media and netizens are bound to make efforts to expose more scandals. [Ibid]

Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “Rampant nepotism and favoritism in officialdom is a major cause of "dead souls". In other words, local officials and leaders simply abuse their power to rob public funds in favor of their families, relatives or friends. In this regard, Chen Wenzhu, the head of the Tobacco Bureau of Shanwei city in Guangdong province, is typical. He hired 22 family members and relatives in the bureau (how many of them are "dead souls" is anyone's guess). Chen is another kind of "dead soul" - he used a false name and identity to obtain residency in Shenzhen, the booming city bordering Hong Kong. He used his two identities to travel to Hong Kong dozens of times in the past six years and authorities are now investigating what he was doing there.” [Ibid]

“Many commentaries in the Chinese media now demand an increase of transparency in the civil service, pointing out that this is the fundamental solution to end the malpractice of "dead souls". In an open economy like Hong Kong, all posts in the civil service are public information and thus subject to public supervision. In such a transparent system, the existence of "dead souls" is hardly imaginable. But this is also means the power of the government and government officials is restricted. Is China ready for this? It seems unlikely - at least in the near future.” [Ibid]

Bureaucratic Hassles in China

Because legal codes are often confusing and contradictory, bureaucrats can interpret them to suit their purposes. Getting approval for something is often a search for the right person with the authority, open-mindedness, desire and will to approve it. One architect told the New York Times , “You go to one person who says yes and then another person says no, We were almost there, and the person died of a heart attack, and we had start all over again with a new person. No one wants to be responsible.”

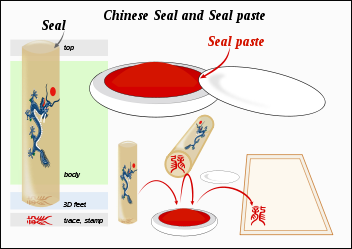

Describing an effort to secure a document of approval for a scheduled meeting, marketing consultant Michael Dinner wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “Arriving at the Zhenjiang government office, your assistant finds two men, a woman and a roomful of silence. Two are gazing at newspapers splayed out on their desks, while the third takes a long pull on his cigarette. The men face each other across worn wooden tables piled with papers...Your assistant still needs an official approval for tomorrow’s meeting. In China, that means getting an official “chop” on a number of documents.”

“The documents first goes to Number Two, who makes sure all the papers are complete and correct. He lays his imprint on the stack and directs your assistant to the woman. The woman maker her own careful review and add her chop, before re-directing your assistant to Number One, the Party member. Number One leans forward, puts out his cigarette, and starts reading...”Are you in a hurry? He asks, as he motions you assistant to sit down on a stool by a desk.”

One bar owner who had frequent run ins with the police told the Washington Post, “I know in China, when they say no, it’s no. You never get a reason why.” One businesswoman told the Los Angeles Times, “Even if you have a lease for 50 years, they can take it back tomorrow.”

A staffer at Ikea in Beijing writes, “It seems that the rules are loosening a bit.” Whether or not they are, a foreigner who taught for two years in China adds, “For every rule in China there is always a way around it.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, November 24, 2010]

Petition System, See Protests; Names, See Language

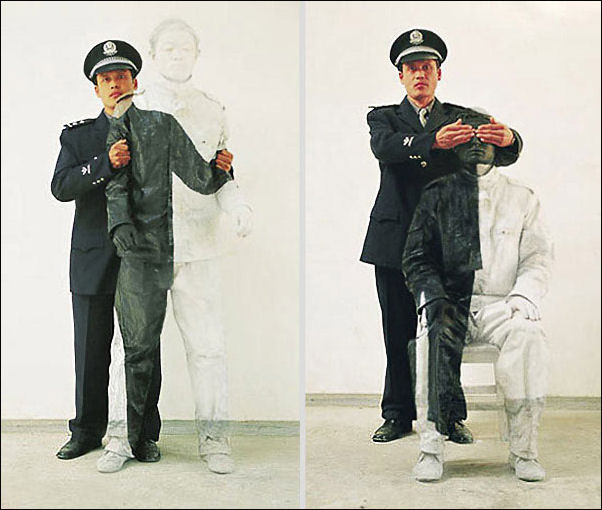

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Red Tape and Bribes in China

For non Chinese things do not happen so quickly. It can two years to obtain permission from local authorities to buy the house and even then it can take skill and guanxi to navigate the process and keeps it form going at en even slower pace. One American promoter told the New York Times, “There is an internal government process in place here that must be followed.”

Some Chinese say that achieving success in China requires skill of navigating through the messy tangle of governmental bodies — national, provincial, city, county township, and even village and neighborhood — and dealing with a certain amount murkiness and not asking a lot of unnecessary questions such as where the money came from.

Opening a hotel in Shanghai requires the approval of 11 agencies, including the police, the fire department and various business licencing bureaus and foreign enterprise offices. Sometimes navigating through the bureaucracy requires proceeding in a step by step fashion from one agency to another but more often means being bounced back and forth between agencies. Foreign businessmen often have to hire dozen or more Chinese to help get through the maze.

Small companies can avoid a $1,400 tax by paying a $140 bribe Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Executive say government and party officials demand payments and abuse their power to award contracts and issue permits. Companies that lowball or otherwise anger officials learn quickly that the most routine inspection can turn into a nightmare...Though cash is straightforward, executives said gifts of department store and restaurant vouchers are more difficult to trace, as are artwork and stock, paid “study” trips, prostitutes or paying overseas tuition of officials’ children.”

Once in Nanjing, a 1,000-ton shipment of steel passed through 83 different government work units and companies before it was delivered. The steel was bought and sold 232 times over several months, increasing the price by 300 percent.

Foreign companies are often restricted from hiring and firing who they want and often they are forced to hire Chinese employees on the basis of their connection not their skills. Simple things such as getting a land-line telephone installed and renting some property can be incredible hassles. Patience is helpful but probably the most important thing to have to get things done is “guanxi” (connections).

Former Shanghai mayor and Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji has been nicknamed Mr. One Chop because of efforts to reduce the number of chops or signatures on permits and bureaucratic documents. In a speech in March 2004, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao promised to cut red tape for entrepreneurs.

Bureaucracy and Ordinary Life in China

hukous Every Chinese citizen is required to carry an identification cards that contain the holder's photograph, ID number, name sex and birth date. They are relatively easy to counterfeit. China is in the process of issuing new high-tech identification cards, with the first issued in Shenzhen in 2007. These plastic cards contain microchips that contain personal information such as work history, educational background, religion, ethnicity, police record, medical insurance status and landlord’s phone number. There is even discussion of adding an individual's reproduction history (as it relates the One-Child policy), credit histories, train travel payments and small purchases charged to the card.

Keeping track of every resident as a way of maintaining control over the population is a practice that has been done since Imperial times. The system worked well under the emperors and Mao because most people spent their entire lives living in one place. These days the system is inadequate in dealing with the all the people moving about in search of jobs and opportunities.

In the Mao era and to a lesser degree today, papers and documents were also needed to get apartments, and receive ration cards and other necessities and benefits. Visas were required on internal passports to travel from one town to another; and when they arrived at their destination hotel guests were required to register with the police.

See Food Safety

Hukous, China’s All-Important Residency Cards

All Chinese citizens need a carry “hukou” (residency card) to live in a city named on the card or move from one place to another. A kind of internal passport, the hukou system was implemented in 1958 to halt migration, control grain rations, and keep tabs on the masses and give rural people a connection to their land. Modern ones are imbedded with chips that have person’s name and place of birth .

A residency card is one of the most valuable documents in China. It is necessary to get an apartment and job in a town or city and send children to school. There are many stories of husbands and wives that are separated because the husband got a good job in a distance town and his wife couldn't secure a new hukou. Peasants migrate to cities without hukous in search of jobs and have trouble getting decent housing and places for their kids in school.

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “One of China's oldest tools of population control, the hukou is essentially a household registration permit, akin to an internal passport. It contains all of a household's identifying information, such as parents' names, births, deaths, marriages, divorces, moves and colleges attended. Most important, it identifies the city, town or village to which a person belongs.” [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

Bloomberg reported: “Large cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Chongqing have a strict quota each year on the number of people who are allowed to become local residents. Almost 10 million people live in Shanghai without a local hukou — more than 40 percent of the city’s population — Huang Hong, chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Population and Family Planning Commission, said in a Dec. 11 post on the local government website. [Source: Bloomberg News, December 17, 2012 |+|]

See Separate Article CHOPS AND HUKOU RESIDENCY CARDS factsanddetails.com

Population Info Database in China

In May 2011, People's Daily Online reported: “A senior Chinese leader has proposed setting up a dynamic national population information database covering each of the country's citizens in order to enhance social administration. Zhou Yongkang, secretary of the Central Political and Legislative Affairs Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), said the database will be based on each citizen's ID card number and include a wide range of personal information. [Source: People's Daily Online, May 3, 2011]

Zhou, a member of powerful Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, stressed that "more than a few" problems exist in current social management, which is becoming complicated and demanding. "The issue of unbalanced, inharmonious and unsustainable development remains prominent, and development gaps as well as income gaps are expanding among regions and between urban and rural areas...A dynamic management system that can cover all the existing population is urgently in need of establishment," he wrote. [Ibid]

Information on each ID card includes name, gender, ethnic group, date of birth, permanent address, ID number and a picture. Zhou called for different departments other than police in setting up the database to include information such as family planning situation, housing, education and tax. [Ibid]

Zhu Lijia, a professor in public management at the Chinese Academy of Governance and a researcher on social management innovation, said running a computer-aided database for the country's 1.37 billion people is not a problem. "The database system can be supportive for social management," he said. "But it is just a means of technology-based management...Real stability, security and harmony must be achieved through institutional reform, and social management innovation must be institutional innovation," Zhu said. The professor also warned that new legal work must be in place to prevent the abuse of such a gigantic and ever-growing database. [Ibid]

Crazy Local Government Rules in China

a hukou

There are numerous examples of dodgy rules created — often with good intentions — by poorly-trained local bureaucrats in China followed by sharp condemnations on the web. In April 2009, one county in Hubei Province in central China drew nationwide ridicule after officials ordered civil servants and employees of state-owned companies to buy a total of 23,000 packs of the province’s brand of cigarettes every year. Departments whose employees failed to buy enough cigarettes or bought other Chinese brands would be fined, the media reported. County officials said their aim was to generate tax revenue and boost the local economy. After several weeks of embarrassment edict was rescinded. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, October 25, 2009]

Officials of Hanchuan, a city in Hubei Province, tried a similar ploy, with the same effect. Determined to boost the local brand of potent baijiu liquor, they ordered state workers to buy a total of about $300,000 worth in a year. Reporters calculated that each employee would have had to buy three bottles a day to meet the quota. The rule was later rescinded. [Ibid]

A county in Guizhou Province in southern China compelled state workers last year to help inflate the number of tourists visiting the ruins of an ancient village by ordering every government office to organize field trips to the site. The Guizhou Commercial News reported that some government offices were left unattended while state employees served as tourists. The journey to the site required taking several buses to get to a village 20 miles from the county seat, and from there, hiring motorcycles to carry them another nine miles down dirt roads, the newspaper Guangzhou Daily reported. That order too was repealed. [Ibid]

In 2003 regulation was put on the books in Sichuan Province that bars male officials from hiring female secretaries. China Youth Daily reported then that the official who initiated the regulation wanted to ensure that work can be carried out. [Ibid]

An order in May 2009 to kill all dogs in the town of Heihe, on the Russian border in the far northeast, media reports suggested, was made by a town official who became irate after a dog bit him as he strolled along a river. Town leaders organized teams of police officers and ordered them to beat to death any dog who ventured into a public space. China National Radio, a state-run agency, broadcast the citizens’ outrage. When we need to walk our dogs now, we have to first go out and look for cops, one dog owner lamented. [Ibid]

Reasons for Crazy Local Government Rules in China

name chop mark

Scholars say the proliferation of such regulations stems from a lack of professionalism among some local officials. The Communist Party has been trying in recent years to correct these problems by providing better training and more channels for public feedback.. Party schools that groom officials now stress administrative skills as well as ideology. Job evaluations are supposed to be based on concrete results. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, October 25, 2009]

Some local officials who used regulations to bilk the public have been dealt with harshly. The party secretary of Feicheng, a town in northeastern China, was fired after imposing a fine of $73 on any farmer who cut down a corn stalk without a license. Farmers complained that they could not harvest their corn without fear of being penalized. [Ibid]

Officials of China’s 637,001 villages seem especially prone to excess regulatory zeal. Until being overruled by higher-ups in 2005, for instance, officials of a village in Chongqing forced unmarried women to pass a chastity test before receiving compensation for farmland appropriated by the government. They argued that only virgins deserved compensation. [Ibid]

School Files in China

Everyone in China who has been to high school has a file — a sealed Manila envelope stamped top secret, containing grades, test results, evaluations by fellow students and teachers, and if they have one a Communist Party application and proof of a college degree. Sharon Lafraniere wrote in New York Times, “The files are irreplaceable histories of achievement and failure, the starting point for potential employers, government officials and others judging an individual’s worth. Often keys to the future, they are locked tight in government, school or workplace cabinets to eliminate any chance they might vanish. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, July 26, 2009]

The files are crucial for getting any kind of good job. Heaven forbid if they ever get lost . But that is exactly what happened to Xue Longlong and 10 others, all 2006 college graduates with exemplary records, all from poor families living in Wubu, a gritty north-central town on the wide banks of the Yellow River. With the Manila folders went their futures, they say. [Ibid]

name chop mark

“While not quite as important as in Communist China’s early days,” Lafraniere wrote , “when it was a powerful tool of social control, the file, called a dangan, is an absolute requirement for state employment and a means to bolster a candidate’s chances for some private-sector jobs, labor experts say. Because documents are collected over several years and signed by many people, they are virtually impossible to replicate.” [Ibid]

“Today, Xue, who had hoped to work at a state-owned oil company, sells real estate door to door, a step up from past jobs passing out leaflets and serving drinks at an Internet cafe. Wang Yong, who aspired to be a teacher or a bank officer, works odd jobs. Wang Jindong, who had a shot at a job at a state chemical firm, is a construction day laborer, earning less than $10 a day...If you don’t have it, just forget it! Wang Jindong, now 27, said of his file. No matter how capable you are, they will not hire you. Their first reaction is that you are a crook.” [Ibid]

Sale of School Files in China

“Local officials said the files were lost when state workers moved them from the first to the second floor of a government building,” Lafraniere wrote. “But the graduates say they believe officials stole the files and sold them to underachievers seeking new identities and better job prospects — a claim bolstered by a string of similar cases across China.” [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, July 26, 2009]

“When the central government talks about the economy and development, it sounds so great, said Wang, the day laborer. But at the local level, corrupt officials make all their money off of local people.” [Ibid]

“Student files are a proven moneymaker for corrupt state workers. Four years ago, teachers in Jilin Province were caught selling two students’ files for $2,500 and $3,600; the police suspected that they intended to sell a dozen more. In May, the former head of a township government in Hunan Province admitted that he had paid more than $7,000 to steal the identity of a classmate of his daughter, so his daughter could attend college using the classmate’s records.” [Ibid]

Image Sources: Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Asia Obscura http://asiaobscura.com/ ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com http://photo.huanqiu.com/creativity/unlimited/2010-11/1254288.html ; Wiki Commons, Wikipedia

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012