ELECTIONS IN CHINA

Over the past couple of decades the Communist Party has been experimenting with elections to fill leadership positions in villages and towns in rural areas. As of 2006, more than 680,000 Chinese villages had held direct elections. Between July 2006 and December 2007, elections for local assemblies were held in 60 percent of provincial administrative regions, with more than 900 million voters selecting 38,000 people’s congresses. No elections had been held beyond the township level.

Over the past couple of decades the Communist Party has been experimenting with elections to fill leadership positions in villages and towns in rural areas. As of 2006, more than 680,000 Chinese villages had held direct elections. Between July 2006 and December 2007, elections for local assemblies were held in 60 percent of provincial administrative regions, with more than 900 million voters selecting 38,000 people’s congresses. No elections had been held beyond the township level.

In 1987, the rural election law was passed. Even today the law is considered experimental because so many top party officials oppose it. Direct elections were tested in the Fujian province in 1987. Posters showed villagers how to vote. Half the villages in the province have voted local Communist party members out of office.

Before 1987 local officials were appointed by high-level party officials and there was no system of accountability. "In the past," one election winner told the Washington Post, "people who had connections with the higher-ups would serve for years and years and years. And they weren't that good in the first place." Sometimes the corruption among local official appointed by the Communist Party was so bad the local people rioted.

In the 1980s, Beijing felt it was losing control of the countryside. Discontent was widespread and villages were thumbing their noses at government family planning polices, staging violent protests, and refusing to pay taxes and meet grain quotas. An estimated 40 percent of villages were out of reach of the government. Many were run by "dirt emperors" and the local thugs that propped them up.

Elections were viewed as a way to bring the countryside back under party control. Kevin O'Brian, a professor at Berkeley, told the Washington Post, "It was effectively a deal, the party allowed the villagers to throw out the old [bosses], but in exchange it mandated that the villagers tow the party line."

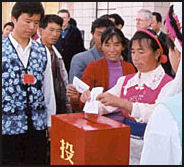

All men or women over 18 are allowed to vote. In villages, such as Dongbaishan in Jilin province, secret ballots are cast in red cardboard boxes, counted aloud and recorded on chalkboards. Unlike elections in the West, a person can cast up to three proxy votes. The head of household often votes for himself, his wife and other members of the family.

LOCAL PEOPLE CONGRESS ELECTIONS: factsanddetails.com ; Articles on GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Wikipedia article on the Government of China Wikipedia ; Chinese Government site on the Chinese Government english.gov.cn ; Carter Center China Program cartercenter.org ;

Local Elections in China

“Mostly unknown to Americans is the fact that China has begun widespread experiments with electoral democracy at the local level,’steven Hill wrote on his blog Truth Dig. “While hard numbers are difficult to come by, China probably holds more elections than any other nation in the world. Under the Organic Law of the Village Committees, all of China’s approximately 1 million villages — home to some 600 million voters — hold elections every three years for local village committees.” [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“The village councils have powers to decide on such vital issues as land and property rights, which are central to local development and the source of increasing tensions (as people are moved off their land, often involuntarily, for the alleged good of China — and all too often to line local officials’ pockets). The central government mandated direct village elections in 1988, soon after the dismantling of the collectivist commune system. The aim then and now was to relieve social and political tensions and help maintain order at a time of unprecedented economic reform. In the past few years that need has become more urgent than ever as more than 70,000 protests and other outbreaks of social unrest have been reported annually in villages across China, oftentimes in reaction to land grabs by local officials.”

“Robert Benewick, a research professor at the University of Sussex who has studied local elections closely, says that village elections have been growing more competitive, with the use of the secret ballot becoming more common. For those elections where there has been real competition, with bona fide independent candidates running, researchers claim to have evidence of positive impacts.”

Yao Yang, a soft-spoken Shanghai-based economist has done considerable research about the impact of local elections. “In a study that looked at 40 villages over 16 years, his research found that the introduction of elections had increased spending on public services by 20 percent, while reducing by 18 percent the spending for “administrative costs,” which is bureaucratic-speak for corruption.”

Critics of these local elections question whether they are genuinely democratic. “Election committees controlled by the Chinese Communist Party often play a significant role as gatekeepers, in many villages deciding most of the candidate nominations. Many of the local elections are rigged, they say, lacking a secret ballot, meaningful oversight or independent review. Vote totals and percentages are not consistently disclosed.”

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief, “Since Deng introduced village-level elections in 1979, little efforts have been made to extend the polls to higher-level administrations. Apparently tried to explain the lack of progress on elections Premier Wen Jiabao said in March 2011 that "this requires a [long] procedure and duration." He added that political reform could only be "implemented in an orderly fashion under a stable, harmonious social environment — and under the party’s leadership," Wen has suggested that the village elections might be extended to the next level of government — township administrations’sometime over the next few years. [Source: Willy Lam, Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, March 25, 2011]

Problems with Local Elections in China

“The economy is improving, society is improving but there is no improvement in elections,” Yao Lifa told The Guardian. He is a 50-year-old, largely self-educated man from the provinces who has tried to work within the local election system. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, May 20, 2009]

He began competing for a seat in his local people's congress in Hubei in 1987, when the election law was first promulgated. After 12 years of harassment and dogged campaigning as an independent candidate, he won. Later he was turfed out again. He has been detained on “at least” 10 occasions, often for promoting voting rights.

The elections are fake, he argues, because the system can't tolerate genuine democratic contests. “The law only states that people have the right to vote; there are no rules to protect this right. When your right to vote is harmed, you can't even set up a case in the court,” he said.

But there is no reason to say western democracy does not fit China. Chinese authorities say people's education level is too low and our economy is still not developed. But how was the economic and educational situation in the west hundreds of years ago?”

Positions and Candidates in Rural Elections in China

Village leaders and the village chiefs are elected but they must be nominated by the Communist Party and they have little power. County governments, under the supervision of Beijing, have more power.

Describing how some candidates are nominated, Steven Mufson of the Washington wrote, "Every resident of the village is handed a blank sheet of paper, and can secretly nominate anyone for office. The posted results give a good idea of who the village’s natural leaders are and how unpopular the incumbents might be."

Candidates running for people’s congresses must have the support of the Communist Party or other affiliated organization or submit ten signatures to run as an independent. Final candidates are selected by election committees controlled by the Communist Party. Officially-supported candidates get their name printed on the ballot and have rallies and meet-and-greet session set up them. Unsupported candidates are prohibited from organizing rallies and voters have to write in their name on the ballot

Rural Elections in Sichuan and Hubei

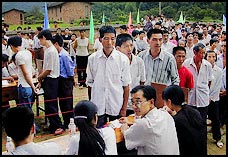

Describing an election in rural Sichuan, Jaime A. FlorCrzu wrote in Time: "There wasn't a lot of choice: four candidates, all picked by the party, for three seats. The 'campaign' was short, fine tuned to predictable platitudes. The candidates — the incumbent village chief, the town treasurer, the chair of the local women's association and the school principal’stood stiffly on stage. They gave brief, stilted speeches, pledging to represent the people's interests."

"By contrast, FlorCrzu wrote, "the voting was festive. Villagers chatted and schoolchildren played. Above, them, paper bunting hanging on a string bore the hortatory slogan: EXERCISE YOUR SACRED RIGHT TO CAST YOUR BALLOT!. Loudspeakers played circa-1970s revolutionary songs."

One longtime local party leader in Sichuan who promised better schools, less pollution and cable television in his campaign speech and won his election told the Los Angeles Times, "I went through the election and now I think that’s the better way. It gave me the chance to talk to people face to face, to find out what their concerns are and to tell them what my thoughts are."

In Qingbui, a village with 450 households in Hubei province, voters have selected a local party secretary in a two-step election: a primary with candidates voted on by village delegates and a run-off with the top two vote getters from the primary. Before elections were held, the party secretary demanded high taxes to pay for building projects that officials had embezzled money from. He lost. The new elected party chief helped get rutted road fix, repair the electrical system and helped farmers make the switch from rice and wheat to cash crops.

Problems with Rural Elections in China

The rural elections are controlled by the Communist party. One village leader told the New York Times, "In the countryside today, the party secretary is in charge of everything. All the political moves are decided by the party before they can be implemented."

In many places elections have been banned, manipulated or rigged. A study by the University of California at Berkeley in seven provinces where "successful" elections had been held, found that less than 20 percent of elections were free and fair.

Vote buying is practiced in some areas. There have been reports of family elders being given $50 to get their entire families to vote for a certain candidate. In January 2007, China prosecuted 192 officials for vote-buying and electoral fraud in village elections.

Elections are often manipulated by corrupt officials, supported by powerful businessmen and real estate developers, who work closely with police. Sometimes officials take ballot boxes to the streets and ask passers by to vote on the spot under the watchful eyes of the officials. Other times supporters of local party leaders going house to house with the ballot box and giving villagers ballots to place in the box. Such practices in Dangxa, a village of 3,200 resident neat the city of Jinan, 320 kilometers south of Beijing, produced a village council that sold off the villagers land to developers.

Voting stations are supposed to deliver the ballots to an official counting station. That doesn’t always happen. Sometimes the ballot boxes are switched and a box with doctored ballots that is taken to the counting station.. Those that complain about suspicious activity are jailed for “disrupting the election” and beaten so severely while in jail they require hospitalization.

Problems Suffered by Candidates with Rural Elections in China

No independent parties are allowed, and even though 40 percent of the candidates who win the elections are not members of the party, nearly all of them have been endorsed by the party before the election and half end up joining the party later. For the Communist party elections are vias a way of spotting new talent.

Candidates running as independents or candidates that the Communist party doesn't like are blocked from taking part in elections or harassed or persecuted in other ways. In Wuhan a candidate was picked up by police for violating election rules and interrogated at key campaigning times. His offense: handing out flyers that called the election illegal and demanded better education and health care. The Washington Post described one candidate the Communists didn't like who was disconnected from the public address system when he began talking about a $210,000 debt village leaders had accumulated.

In 2006 about 10,000 people ran as independents in elections for people’s assemblies, up from around 100 in 2003, but only 0.5 percent won seats.

In 2003, independent and reform candidates in Hubei complained they were cheated out of victories through intimidation, gerrymandering and foul play. In other places independent candidates failed to advance beyond the primary stage for reasons that were not known because the election results were not released.

When controversial candidates are elected they are often ignored or harassed. In many places regardless of who is elected the Communist's village branch remains the "leadership core." In the village of Qixia in Shandong, local elected leaders have clashed with entrenched Communist Party officials accused of brazen corruption with the officials prevailing in the end, often by intimidating and beating up the elected officials and their supporters.

Efforts to Reform Elections in China

In October 2003, President Hu Jintao made calls for more democracy but was vague about what he actually meant. Some saw this as an encouragement to persue more open elections.

In August 2003 in the township of Pingba in southwestern, a low-level party official named Wei Shengduo organized a direct election for the head of the township government, a position usually appointed for party bureaucrats. The day before the election Wei was arrested and the election was canceled.

Wei turned to democracy as a way of to help his badly-in-debt township solve its financial problems. His reasoning went that if people had more of a say in government affairs they would be more willing to pay taxes because they would have some input into the way the tax money was spent.

In 2003, a law professor in Shanghai named Hu Dezhai was attempting to get laws upheld that any candidate could run for office and gethis name on the ballot as a write-in candidate if he got ten signatures on a petition. The same year in Beijing, a university student named Xu Zhiyoing got his name on the ballot for a seat in the People’s Congress without Communist Party support and won.

In 1994, peasants in the rural Hebei province complained to party official that an election was rigged, and the election was investigated and the results were overturned. In 1998, people demanding an election in village in the same province rioted and fought with 700 riot police. One villager was killed.

See Protests in Taisha Under Corruption

Election Plan in Shenzhen

Shenzhen has been selected to be the site of a test case for expanding the powers of the local legislature, allowing direct elections for some local officials, creating a more independent judiciary and promoting greater openness and accountability within the party. The plan, formally approved in June 2008, was concocted over three months by 24 specialized teams assigned by the Shenzhen mayor to make Shenzhen “a model for socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

According to the plan the local People’s Congress, or legislature, will be given the power to supervise the local executive branch and be accountable to the people by allowing an expanding number of candidates to run in elections. The judiciary, according to the plan, should “independently exercise its rights to judge and supervise.”

Experiments with “Deliberative Democracy” in China

Steven Hill wrote on his blog Truth Dig, “China’s modest experiments with local electoral democracy have been supplemented with exercises in what is known as “deliberative democracy.” These take the shape of New England-style town hall meetings, review hearings and public consultation exercises. China hired Stanford University professor James Fishkin to draft a randomly selected, scientifically representative sample of citizens from the city of Zeguo to participate in a process so they could decide how their city should spend a $6 million public works budget. Fishkin’s signature “deliberative polling” method employs technologies such as the Internet, keypad polling devices, handheld computers and more to convene representative assemblies of average citizens for several days. [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“The Zeguo exercise was considered hugely successful and has been replicated in other places. Interestingly, it jibes well with the governance vision of those who want to see China develop into a sort of high-tech “consultative dictatorship” in which the leaders use various technological means to keep their fingers on the pulse of the people, a kind of 21st century version of Plato’s philosopher-kings ruling for the good of society.”

“Given China’s remarkable development over the past three decades under a succession of fairly competent leaders, this vision does not seem far-fetched, at least in the short term. But in the longer term, critics of this approach see the Chinese dictatorship — however consultative — choking off the creativity and entrepreneurial flourishing that is necessary to allow the growth of China’s business sector and macro-development.

Step by Step to Democracy in the Party Congress”

In July, 2008, the Chinese Communist Party announced that it has adopted a “tenure system” that will give real power to traditionally rubber-stamp delegates to party congresses. Traditionally, party elites made all the decisions. What that means exactly depends on how the system is implemented. The whole effort could turn out to be yet another exercise in official hypocrisy. [Source: Kent Ewing, Asia Times, July 25, 2008]

“Kent Ewing wrote in the Asia Times: “The limited brand of democracy being trotted out by Beijing will not give a political voice to the common man or woman or brook any opposition to communist rule. It will, however, give party delegates more say in their country's affairs and, hopefully, create a system of checks and balances that will lead to greater efficiency and better decision-making. Moreover, the leadership is desperate to come to grips with the massive corruption that has become a way of life for officials, especially at the local level, and sees so-called “intra-party democracy” as a way to do that.

“China's move toward greater democracy is set to happen at such a carefully slow pace that it is likely to go largely unnoticed in the West. But it is nonetheless a potentially significant development...That's why the recent CCP announcement about the tenure system should be welcome news. True, it is a small step. But that is how every long journey begins.”

“While party congresses are likely to remain heavily scripted affairs for the foreseeable future, the tenure system is aimed at granting national delegates greater and more meaningful participation in party affairs before a congress takes place. The new initiatives allow delegates to attend party meetings throughout the year, offering suggestions and feedback. The open invitation apparently includes the plenary session of the central committee, usually held once a year. In addition...delegates may take part in meetings of the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI), the party's top anti-graft body, where they can monitor committee reports and even challenge them if they see fit.”

“Taken at face value, all this means that the central committee and the CCDI will now be accountable to delegates whose previous role was mostly ceremonial. And changes at the national level are being mirrored by changes in the way party committees will be run at the provincial and local levels. Local delegates have been promised a role in party appointments and in the evaluation of those who receive those appointments. They will also be encouraged to meet when party committees are not in session for discussion of important issues and to research and investigate party decisions.”

“Again, establishing checks and balances for a one-party system that is reeling out of control is the goal - but there may be a hitch: the party committees that delegates would be investigating are at the same time responsible for paying the costs involved. How many of the legion of corrupt local and provincial officials are going to be willing to fund a probe that would reveal their venality? Of course, Xinhua's report promised that such obstructionists would be found out and punished, but, at this point in China's development, that needs to be seen to be believed.”

Internal Party Democracy in China

Steven Hill wrote on his blog Truth Dig. “Yu Keping and others have been nudging democracy forward in another direction that some think may have the most long-term promise — internal party democracy within the ruling Communist Party itself. The idea would be to rejuvenate the party from the bottom up by holding competitive elections for all party posts. This already has begun at lower levels, with votes for provincial and national party congresses showing electoral slates with 15 to 30 percent more candidates than positions. [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“Given that the Communist Party has a membership of 73 million people — larger than most nations’such a “democratic vanguard” holds potential. The Vietnamese Communist Party — whose structure historically has mirrored China’s — introduced competitive elections for its party chief several years ago, and some insiders think this may be a harbinger for China. Some are encouraged by the fact that the current president, Hu Jintao, is the first not to handpick his successor, who instead was selected as the result of a secret poll of Communist Party officials. That shares some features with how parliamentary democracies choose their prime minister via a vote by members of parliament, except in China’s case it’s all done in secret and the people voting for the leadership are unelected.”

“If internal elections become more widespread, then the lines of ideological difference within political elite circles might become more clearly drawn, which could further spur calls for some kind of representational structure. From the outside looking in, Chinese political and ideological thought looks fairly rigid and monolithic, but from the inside already there are signs of opposing viewpoints and dissent, with a “left” and a “right” emerging.

“The dominant policy since the late 1970s established the primacy of the free market, but today this is being challenged by a new left which advocates a gentler form of capitalism. A very progressive battle of ideas is pitting the rich against poor, the coasts against inland provinces and cities against the countryside. Some of the most powerful authorities appear to be listening to the progressive critique, at least with one ear. At the end of 2005, the Chinese leadership published the “11th five-year plan,” its blueprint for a “harmonious society,” and for the first time since the post-Mao reforms began in 1978, economic growth was not described as the overriding goal for the Chinese state. The leaders talked instead about introducing the bare bones of a progressive, European-style support system, with promises of a 20 percent year-on-year increase in pension funds, unemployment benefits, health insurance and maternity leave...While currently playing out in published polemics, on the Internet and in the party congresses, internal Communist Party elections could become a natural outgrowth of these existing debates.”

How Realistic is Chinese Democracy

Steven Hill wrote on his blog Truth Dig, “So perhaps some bold but slow-forming experiment in representative and meritocratic democracy is now on the table, yet numerous cynics and Western sinologists continue to say, “Don’t hold your breath.” China’s rampant corruption, as well as the deep involvement of the military in running businesses and controlling everything from major amounts of real estate to dealerships in ancient art and antiquities, points to the illusion of this wishful thinking, they say.” [Source: Steven Hill, Truth Dig, December 15, 2010]

“But the cynics usually don’t factor in a new, younger generation of people and leaders who are developing different sensibilities than their forebears. One female graduate student I met at Beijing University displayed an uncommon affection for electoral democracy and the exercise of free speech rights. This student had spent a year studying at the University of Washington (a surprising number of the Chinese elite have spent time at American and European universities). When the Dalai Lama came to Seattle, she and some other Chinese students decided to protest. “Heavens, why would you protest the Dalai Lama?” I asked her. She looked at me with disbelief. “Why, the Dalai Lama is a king,” she said, as if stating the blatantly obvious. “He’s a monarch, totally contrary to any notions of democracy. He hasn’t been elected to anything.”

“These Chinese students filled out their protest permits at Seattle police headquarters, and were shocked when their permit was denied. “Here we are in America, the land of free speech, trying to exercise our so-called constitutional rights, and they tell us we can’t protest when this king shows up claiming to speak for people in the Chinese province of Tibet.” I chuckled at another Chinese belief — the Dalai Lama as an unelected king — aiming to overturn conventional wisdom.”

“If democracy is good for Tibet, why not for all of China? That’s a small ideological leap to make. Perhaps if their belief in democracy is strong and ecumenical enough, the youths of China will find a way to take their country down a path toward greater popular sovereignty. It remains to be seen how much of the “new China” will continue to emerge as this drama plays out, but it’s very likely that any Chinese democracy will have its own unique characteristics; it is unlikely to be an exact copy of the Western model, and it will take its time arriving. China is both a modern state and an ancient civilization that, after all, has shown an almost pathological degree of patience and forbearance. This is the nation where Zhou Enlai, the legendary prime minister under Mao, was asked what he thought of the French Revolution and is said to have replied: “It’s too early to tell. The same could be said for the prospects of representative democracy in China.”

Opposition Parties in China

There are eight so-called democratic parties sanctioned by the government. They include the China Democratic League which fought against the Kuomintang and helped establish Communist China in 1949. The relationship between the Communist Party and the eight parties is based on “long-term co-existence and mutual supervision.” During the anti-rightist campaign in 1957-58 the eight parties were forced to submit to the Communist Party and their leaders were charged with crimes and imprisoned.

The China Democratic Party (C.D.P) is the only party in China that has registered as an independent party. It was formed in the 1980s and several of its leaders have been in prison for many years. Zha Jianguo, one of founders, was serving the eighth year of a nine year sentence in 2007. His sentence was not reduced because he refused to admit to committing any crime. Most Chinese have never heard the CDP. The New York Times dismissed it as “a toothless group of a few hundred members writing essays mainly for one another.”

In 2007, Guo Quan, a young professor at Nanjing University, called for the creation of the New Democracy Party to oppose one-party rule. He was stripped of his professorship but surprisingly was not arrested.

Image Sources: 1, 2) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3, 5, 6) Carter Center; 4) Wellesley College

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2011