TAXES IN CHINA

Types of Taxes: business taxes, income tax and VAT sales tax. The Value Added Tax (VAT) was 17 percent in 2004. Income Tax: The average Chinese paid just $16 in income tax in 2004. Only about a 7 percent of total tax revenues come from income tax.

Types of Taxes: business taxes, income tax and VAT sales tax. The Value Added Tax (VAT) was 17 percent in 2004. Income Tax: The average Chinese paid just $16 in income tax in 2004. Only about a 7 percent of total tax revenues come from income tax.

Tax revenues reached $480 billion in 2006 ($370 person), up 22 percent from the previous year but still only a fraction of the $2.5 trillion ($8,297 per person) collected on the United States. Most of the $318 billion in national taxes collected in 2004 came from businesses and industries. Little came from personal income tax. Little also came from taxes from small business which can easily hide their assets and the money they have earned.

Only people who make more than $100 month are required to pay taxes. Only a minority of Chinese make that much. Of those required to pay taxes many get out of paying them through loopholes, lax enforcement or simply not paying. Paying income tax is still a relatively new concept in China.

The preferential treatment given foreign companies on tax payment was largely abolished with new tax laws in 2007. Now both foreign and domestic companies pay a tax of 25 percent of their profits. Under the old system Chinese companies paid as much 33 percent and foreign companies as little as 10 percent.

Beijing is attempting to tackle the income disparity problem by implementing a more progressive tax system and cutting taxes for the poor while closing loopholes and preventing cheating by the rich.

Tax revenues have grown with overall economic growth. Despite high revenues China has run up deficits as it spends more than it takes in to give more aid to farmers and the poor.

The government has made out well with a turnover tax on share trading on the stock market and its taxes on tobaccco products. Tobacco Taxes, See Smoking, People and Life

Complaints About New Foreigners Tax

In October 2011, a new tax on foreign workers was introduced that mandated they pay social security contributions. Foreign executives in China have expressed concern that the scheme will increase costs in the world's second largest economy, and that the plan is too vague and will be hard for companies to implement. [Source: Reuters October 30, 2011]

Reuters reported: Complaints about the new tax are misguided and unfair, and foreign firms in China have no right to expect special treatment, the official Xinhua news agency said. An official acknowledged that they had jumped the gun in rolling out the rules before the government had worked out exactly how the system would be implemented, but said there would be no going back.

Xinhua, in an English-language commentary, scolded foreign firms for assuming they are "entitled to favourable policies while operating here...As China continues to make changes to its market economy, the equalization of treatment for domestic and foreign firms has become an irreversible trend. The lenient policies of yesterday have worn out their usefulness, and foreign companies should keep that in mind...It is logical that as the economy grows, labour costs will rise accordingly. The idea that rising costs eat up China's competitiveness is arbitrary in nature. The age of ultra-low labour costs is nearing its end.”

China is following international norms by including foreigners in its social security net, Xinhua said. Such commentaries are a reflection of government thinking rather than an official statement of policy. "Ample opportunities exist for foreign investors who are eyeing China for future growth. Rather than airing grievances, they should simply change their China strategy and share more knowledge with their Chinese partners," it wrote.

China's new rules will make it more like policies in many EU countries, where citizens and foreigners alike pay into the system.The commentary made no mention of the problems the government says it has yet to work out with the system, such as how foreigners are supposed to pay when local tax offices say they remain unclear on how to accept payments. Xinhua also gave no clue as to how foreigners would be able to access services such as unemployment benefits, since work visas are tied to jobs and become invalid when a worker is laid off. The government says it its trying to come up with a solution to these issues as soon as possible, although the rules went into effect on Oct. 15, 2011.

Chinese Tax Collectors

Traditionally tax collectors would collect taxes and payments for "school repair" which went directly into their pockets. Under a new rural tax system, 140,000 tax collectors were laid off or given new positions and farmers were required to pay their taxes at town tax offices. Farmers were very happy about the system and have showed up at town offices to pay their taxes.

The government is trying to step up its tax collection efforts, especially from rich entrepreneurs.

The government is aiming to collect more taxes from small businesses by requiring the businesses to give out receipts and encouraging customers to demand receipts and then collecting these receipts to see if they match up with records the businesses keep on their books.

“Happy Draw”, a television game show aimed at getting more people to collect receipts, features guests who can use receipts they have collected like lottery tickets to win prizes or perform stunts that can lead to winning prizes. Describing the show, James T. Areddy wrote in the Wall Street Journal: “Some prizes went to winners of a game of chance. When contestant pressed the lever of a box meant to resemble an old-fashion TNT detonator, a number popped out showing the size of the cash reward. Other times it was skill of a certain kind. Ms. Li and others were given oversized red shoes and asked to skip across the lighted floor panels. She did it the fewest steps and moved to the final round.”

Unfair Taxes in China

Excessive taxation, local corruption and declining incomes are problems faced by many people in the countryside. In many places officials impose high taxes and then siphon off the money for S.U.V.s and drinking, karaoke parties and prostitutes.

Under Chinese law, the government cannot tax farmers more than 5 percent of their income but that doesn’t stop tax collectors from collecting more. In some places where farmers only earn about $44 a year after they pay for fertilizer seeds and supplies. This means they should pay $2. Instead they are taxed $36. Farmers who resist have their food and cash crops taken by cadres and have high fines slapped onto their tax bills.

In some cases officials tear down homes and severely beat people who don’t pay their taxes. One man who demanded to see how his tax money was spent was attacked at home by thugs who took away his family's pigs and food supply.

Farmers are poor but often pay proportionally more taxes than everyone else. One farmer from Anhui province told the Asahi Shimbun, “If were discharge smoke, we have to pay a pollution tax. When we get married they tell is we have to pay a marriage tax.” In some cases after they pay their taxes they have little or nothing left over other than the food they stashed away to eat.

Taxes that often eat up more than half of farmers’ annual incomes. The taxes are sometimes collected corrupt officials who are trying to enrich themselves. Often though they are collected by bankrupt governments desperate for revenues to provide basic services. In recent years farm taxes have been reduced and eliminated.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, “When I looked at rural unrest in China a decade ago , I was surprised that many farmers found out by watching television news that they were being overtaxed. Aware that local officials were overtaxing locals and causing riots, the authorities in Beijing broadcast new tax codes, making sure that people knew that it was not government policy to tax them to death. Some locals rioted and many others filed class-action lawsuits — but in the end local taxation was reduced (and eventually eliminated entirely). This wasn’t despite central government efforts, but because of them. The result is that rural protests, which were a regular feature of 1990s China, are far less common.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, December 22, 2011]

Tax Revolts in the 1990s in China

In May 1998, unhappy farmers staged a demonstrations to demand tax relief. When a provincial Communist Party officials tried to negotiate he was taken hostage. A thousand riot police were called in before it was over numerous people were injured and 28 cars were damaged. Eleven people were arrested. A leader was given a sentence of 11½ years in prison.

In January 1999, a revolt broke out after a peasant committed suicide because he couldn't pay an arbitrary tax on slaughtered pigs levied by a local official to coincide with the Chinese New Year. Over 10,000 angry peasants marched on party headquarters, overturned the cars of Communist officials. The People's Armed Police had to called in to restore order.

Tax Revolts in the 2000s in China

In April, 2000 villagers in Jianxi clashed with police during a demonstration on taxes. Near dawn 500 armed troops and police fired into a crowd, killing two peasants and wounding 18 more. The peasants had been quarreling with officials for three years over excessively high taxes. Jiangxi had a series of problems. Much of it began in 1998, when farmers had their taxes raised even though many lost their crops to Yangtze River floods.

In August 2003, more than 10,000 farmers in Jianxi protesting high taxes rampaged through the offices and homes of Communist Party officials. In January 2004, villagers protesting high taxes in Yutang in Jiangxi were shot at by troops. Two men were killed.

The government is trying to help the farmers by offering more relief and cracking down on the officials that try to cheat them. In some places where reforms have been implemented farmers pay two third less than they used to. Taxes on smoking and marriage were eliminated. The problem is that local government bodies that relied on the money from the central government during the Mao era no longer receive it and have to make significant cuts or find ways to increase revenues.

Local Government Funding in China

The Economist reported: China’s local governments carry out over four-fifths of the country’s public spending, but pocket only half of the taxes. To help make up the difference, they rely on expropriating land from farmers and flogging it to bullish property developers. But as developers struggle, land sales are dwindling. As a result, local-government revenue is drying up. Popular resentment, meanwhile, is not. In Wukan, in the southern province of Guangdong, aggrieved villagers rose up in December against land-grabbing officials, chasing the local party chief away. [Source: The Economist, Feb 4, 2012]

By some estimates local government receive half their funding from real estate transactions. Typically they acquire farm land, put in some minimal infrastructure and sell the land to developers. During the reform years funding was cut off and authority became decentralized very quickly and governments had to scramble to come up with ways to make money. Real estate and land seizures proved to be a relatively easy way to make a lot of money.

The system encourages corruption and short-term thinking. Officials often only serve five year terms and there is an incentive for them to make money quickly before their term is up.

Zhu Rongji’s Tax Sharing System

Zhu, Rongji served as premier from 1998 until 2003. Before that he initiated and implemented a tax sharing system that gave the central government the lion's share of the country's taxation revenue. Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “Zhu's first move, after he was appointed as vice premier in charge of economic affairs in 1991, was to reform the taxation system so that the central government could have more money. After months of tough negotiations and bargaining with economically important provinces on how much they should contribute to the state coffers, Zhu eventually introduced the tax sharing system at the end of 1993.” The move was made in response to Deng Xiaoping economic reforms that gave regional governments greater say on local economic affairs, meaning central government had less and less revenues at its disposal. [Source: Wu Zhong, China Editor, Asia Times, June 22, 2011]

According to the tax sharing system as introduced by Zhu, the state would take a large proportion of the revenues and then give rebates to regions. However, the rebates were given back indirectly and not in a lump sum, rather taking the shape of subsidies on infrastructure, education, welfare and other sectors. This has given central government authorities much greater powers.

Under the system, each province would contribute a certain proportion of its taxation revenues to state coffers. While the proportion of contribution varies from province to province, on average the central government nominally could have a 60 percent-70 percent share of the nation's fiscal revenues while the rest would go to the regional governments. Afterwards, the central government would give back some funds to regional governments according to agreed proportions. The reform boosted the central government's revenues from 4.35 billion yuan in 1993 to 2.17 trillion yuan in 2003 when Zhu retired.

Criticism of Zhu Rongji’s Tax Sharing System

Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “Zhu apparently feels proud of the tax sharing system, seeing it as one of his great achievements even though the system’s arrangement for tax rebates to the regions had become a hotbed of official corruption, as central government officials often took bribes before returning funds to the regions. [Source: Wu Zhong, China Editor, Asia Times, June 22, 2011]

In a speech at the Tsinghua School of Economics and Management in April 2011, the 83-year-old Zhu responded to assertions that China’s real estate problem stems from the tax sharing system by saying “This is bullshit!" To support his argument, Zhu gave a breakdown of revenues between central government and regional governments for 2010. This was the first time such figures have been made public. According to him, China's fiscal revenue totaled 8.3 trillion yuan (US$1.28 trillion) last year, of which 4 trillion yuan directly went to regional government coffers. Then, following the tax sharing system, the central government gave the regional governments another 3.3 trillion yuan from its own share as rebates. "As a result, the regions got 7.3 trillion yuan in total. Still not enough? Still poor? Now regional governments have plenty of money," Zhu said.

Zhu angrily lashed out at a book that is still officially banned in China, Zhongguo Nongmin Diaocha (An Investigation of China's Peasantry) by the husband-and-wife authors Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao. The book blamed the tax sharing system for hardship in rural areas, arguing that because of the system local governments lacked funds to support compulsory education, family planning and social security and welfare. In response Xhu said, "Tax rebates are not done well. Regions have to curry favor with relevant ministries to beg for their rebates. There are shortcomings in the tax sharing system, which however I am not entirely responsible for. For, I had said long ago that the taxation reform was far from over and should be deepened."

Land Seizures and Local Government Revenues

About 40 percent of local government revenue came from land sales in 2010, year, according to China Real Estate Information Corp., a property data and consulting firm. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The land issue looms large in the countryside. Local governments earned $470 billion from land deals in 2010, up from $70 million in 1989, according to the Ministry of Land and Resources, and farmers — who lease their land rather than own it under the communist system — have scant protection if local officials want to give the leases to real estate developers who will pay more. Compensation is often inadequate. Chinese laws designed to protect farmland by requiring permission from the State Council — in effect, the country's Cabinet — for transfers are widely ignored by local officials. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2011]

Yu Jianrong, a professor and expert on rural issues at the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimates that local officials have seized about 16.6 million acres of rural land (more than the entire state of West Virginia) since 1990, depriving farmers of about two trillion yuan ($314 billion) due to the discrepancy between the compensation they receive and the land's real market value. [Source: Jeremy Page and Brian Spegele, Wall Street Journal, December 15, 2011]

Jeremy Page and Brian Spegele wrote in the Wall Street Journal:In 2010 alone, China's local governments raised 2.9 trillion yuan from land sales. And the National Audit Office estimates that 23 percent of local government debt, which it put at 10.7 trillion yuan in June, depends on land sales for repayment.

Migrants Protest Over Tax Dispute in East China

In October 2011, AP reported: “Hundreds of migrant small business owners in an eastern Chinese town have protested over a tax dispute, some of them torching vehicles, in the latest unrest resulting from growing economic pressure and anger over the unfair treatment of migrants. The group of children’s clothing company owners protesting in the town of Zhili in Zhejiang province swelled to more than 600 people, on Wednesday night, according to Huzhou Online, a state controlled news portal in the city of Huzhou, which oversees Zhili. [Source: Associated Press, October 27 2011]

The protests started after one of the business owners refused to pay taxes and gathered a group to attack a tax collector, the report said, adding that some of the protesters blocked a highway and smashed and torched vehicles. The report did not explain why the business owner did not want to pay his taxes. But a local doctor surnamed Zhao contacted by The Associated Press said he had heard that town authorities were imposing a higher tax rate for migrant businesses than for local ones, causing unhappiness among the group who were from neighboring Anhui province.

The Huzhou Online said police had detained five suspects and that another 23 suspects were being held as part of the investigation. Around 100 protesters swarmed toward the township government offices, hurled rocks and destroyed street lamps, smashing the windows of more than 30 private cars, said the Zhejiang Online, a provincial news website. It added that several police and urban management officers were injured. Protesters also smashed an Audi car, whose driver ran the vehicle into the group, knocking down 10 people, the Zhejiang Online said. All 10 were hospitalized and the driver was being held by police, it said.

Reasons Behind Migrants Protest Over Tax Dispute in East China

The unrest is the latest sign of tensions arising from economic pressure. People are unhappy about the tax burden at a time when household incomes in a lot of areas are stagnant but living costs are rising rapidly. Inflation has been largely driven by food costs and the government has launched measures to increase supplies but those have been set back by summer storms that wrecked crops. Huzhou, like much of Zhejiang, is full of small-scale private factories staffed and in some cases now run by migrants from neighboring Anhui and Jiangxi provinces. These factories run on thin profit margins in the best of times and higher taxes add to the pressure.

There is also a growing unhappiness over unfair treatment of migrants, who usually perform the most dangerous and least desirable work in China and are widely seen as vulnerable to abuse and discrimination by authorities and local residents. In June, thousands of migrant workers rioted in the southern city of Xintang after a confrontation between security guards and a pair of migrant sidewalk vendors.

The Wall Street Journal reported: According to people interviewed by telephone in Zhili, the disturbance followed aggressive collection of new charges for the use of machines used to make children’s wear, the town’s mainstay product. The tax was targeted at small, independent workshops that often aren’t licensed and are manned mostly by migrant laborers who earn money per piece produced. They said workshop managers were being charged between 300 yuan (about $48) and 600 yuan for each machine used, in what Chinese discussing the matter online called the “sewing-machine tax.” It amounts to about twice as much as was collected in the past. An unidentified man who apparently objected to the payment rallied others to join this week’s protest, locals said. [Source: China Digital Times, October 28, 2011]

China’s economy is slowing and the Zhili government’s pullback on tax levies reflects a strategy Beijing is increasingly likely to take to soften pain of the deceleration, according to analysts. This week, the central government said it would reduce double-taxation of certain transportation in China, a move expected to encourage some business activity and amounts to a philosophical change, according to analysts.

This tax reform is part of the structural tax reduction, and thus can be viewed as a signal of expansionary fiscal policy,” Minggao Shen, a Citigroup economist said in a research note. The influence on China of a weak global economy is clearly being seen in Zhejiang province, home to nearly 50 million people and by some measures the country’s wealthiest region. Nearly 12 percent of China’s total exports came from the province in August. But Zhejiang factory owners say their already-thin margins are disappearing.

Time for a Chinese Property Tax to Stabilise the Wild Property Market?

In February 2012 The Economist reported: In other parts of the world local governments raise revenues by taxing homes based on something like their market value. In China taxing property is a touchy subject. The government had tried imposing a variety of levies on the sale, size and historical cost of property, but none on the market value of homes. That changed a year ago, when Chongqing and Shanghai, two giant cities, introduced a pilot tax on some upmarket homes. The tax was largely symbolic, levied at low rates on a few thousand homes in each city. But it nonetheless set a precedent. China should now broaden that tax to as many properties as possible, in cities across the country. [Source: The Economist, Feb 4, 2012]

For local governments a fully fledged property tax would provide a stable source of revenue. Unlike workers or businesspeople, homes cannot up sticks and leave. A property tax raises revenue year after year, in contrast to a land lease, which can be sold only once. What’s more, such taxes allow local authorities to capture some of the value they create: as they invest in local amenities, property values rise, and so do the taxes they are able to collect.

A property tax could also temper the wild swings in China’s housing market. A recurring levy would make it costlier to buy and hold a second or third home as a speculative bet on rising prices. That would force some absentee homeowners to sell their vacant flats or rent them to the many citizens priced out of the market. Some economists believe that the light taxation of land in Japan contributed to its ruinous asset-price bubble in the 1980s.

A property tax would by no means be easy to implement in China. It would require homes to be registered, title to be clear and the appraisal of property values to be credible. But similar obstacles have been overcome in other developing economies, including many cities in India.

Under Chairman Mao, taxes on private property all but vanished along with private property itself. Today’s Chinese set no store by the old socialist doctrine that “property is theft”. But many urban Chinese now think of taxation that way. They feel, with some justification, that they already pay too much to a state that provides too little.

This antipathy is not lost on China’s local governments. They are wary of angering the urban middle class, who own their own homes, and the city elites (including party officials and their families), who usually own several. So they continue to cause anger by throwing rural folk off their land. China must now act boldly to reform its taxation of property. Otherwise it will have to face the consequences of continued weak local-government finances and even more social unrest.

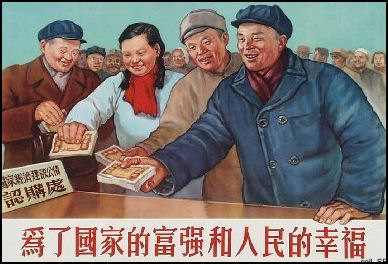

Image Sources: Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012