POLITICS IN CHINA

Hu Jintao pressing the flesh Chinese-style

The Communist Party lacks rules for decision-making and even titles sometimes have little meaning. There are few rules and when there are rules they are often not followed. Personalities are generally of greater importance than policies. Seniority also seems to be important with former leaders and party elders often wielding their power behind the scenes. Things always tend to get interesting in China before a National People’s Congress, where leaders are anointed and the results of backroom maneuvering are on display.

Chinese politics is characterized by backroom deals, alliance building, maneuvering against rivals, power shifts among individuals and alliances, compromises among enemies, and purges. Much of what goes on is murky and occurs behind the scenes. Much of what occurs in public seems only to be an affirmation of what has occurred in secret. Ian Buruma wrote on Project Syndicate: In China, everything takes place out of sight. Because leaders cannot be ousted through elections, other means must be found to resolve political conflicts. Sometimes, that entails deliberate public spectacles. [Source: Ian Buruma, Project Syndicate, May 4, 2012]

Understanding the intricate workings of a government can be difficult, especially in a country such as China, where information related to leadership and decision making is often kept secret. In examining the workings of a nation's foreign policy, at least three dimensions can be discerned: the structure of the organizations involved, the nature of the decision-making process, and the ways in which policy is implemented. These three dimensions are interrelated, and the processes of formulating and carrying out policy are often more complex than the structure of organizations would indicate. [Source: Library of Congress]

A great deal of time is taken up by sitting through lengthy meetings which accomplish little and sifting through lengthy documents and paperwork that are largely waste time. In 2007, the State Council set limits on the lengths of official meetings, speeches and documents.

China has a top heavy approach to decision making, requiring layers of approval before a decision is made. Government workers are not elected and often feel little pressure to respond to public concerns. Dissent mostly takes the form of “petitioning the court,” a practice that dates back to dynastic times.

Among the masses controlling group behavior is key. Maureen Fan wrote in the Washington Post: “China’s political culture places a unique emphasis on group performance. It’s an emphasis that starts as early as kindergarten, dominates the work lives of state employees and is used to demonstrate collective passion, where it might not. otherwise exist. To...visitors the impulse to script and stage manage everything might seem odd. But China has long emphasized ceremony and propriety.”

"China's philosophy is to do things gradually because they don't like dramatic change," Li Jie, head of the Reserves Research Institute at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, told the Los Angeles Times. "We have a saying: 'You don't cry until you see the coffin.' They don't have an incentive to change the status quo."

CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY , POLITICS AND POLITICIANS factsanddetails.com and GOVERNMENT OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on the Communist Party of China Wikipedia ; China Today, official Chinese government source on the Communist Party of China chinatoday.com ; History the Chinese Communist Party at China.org china.org.cn ; Wikipedia article on the Government of China Wikipedia ; Chinese Government site on the Chinese Government english.gov.cn ; Carter Center China Program cartercenter.org

Chinese Politicians

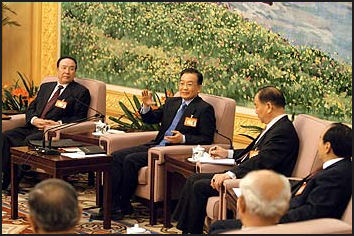

Meeting with Premier Wen Jiabao

Chinese Party politicians portray themselves as serious and loyal to the party. At party meetings they are shown lined up in rows, dressed in the same dark Western suits, clapping in unison to speeches by their leaders, with individuality occasionally expressed with oversized glasses or slightly permed hair. They tend to give away little about their personalities, their personal and private lives, and their views on policy matters.

The Communist leaders of China are for the most part former engineers. Rana Foroohar wrote in Newsweek, “China’s faith in its ability to mold markets may derive from the fact that its leaders are mostly engineers, trained to build from a plan. Eight of nine top party officials come from engineering backgrounds, and the practicality of their profession may help explain why they didn’t buy into risky (and Western) financial innovation. These ruling engineers preside over a system that is highly process oriented and obsesses with performance metrics.”

There is a Chinese tradition of public figures honoring good works with their own handwriting, often with a signed note offering good wishes or respect

Every leader at virtually every level has to be appointed, approved or otherwise sanctioned by the Communist Party. Under ancient Chinese system of patronage, which is still followed today, officials received appointments from above in return for remuneration from below. And people who collected taxes and other payments kept some for themselves and passed on the rest to their superiors.

Promising new members are generally recruited in the cities not the countryside. Minxin Pai of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said, “the party showers the urban intelligentsia, professional and private entrepreneurs with economic perks, professional honors and political access."

The career of ambitious Communist officials is not unlike that of officers in the American military. Ambitious young officials are rotated through a series of management posts, punctuated with mid-career training at party schools. They are evaluated at the end of each command post, which determines whether they advance or are sidetracked.

Power and Politics in China

Meeting with Wen Jiabao and Vice Premier Wu Yi

The goal for ambitious politicians and officials is to win a place on the Central Committee, with this leading to a governorship of a province or a post as a regional party secretary, with the aim of ultimately making it to the Politburo.

Dutch journalist Willen van Kemendade wrote in his “book China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Inc.”, the central authorities "most effective instrument" is "the power to appoint and dismiss governors, party secretaries and regional army commanders."

Maintaining power is often a balancing act between rival factions The Chinese ruler must lead as a first among equals. "He can't just issue edicts," one diplomat told Time magazine. "he has to marshal a consensus.”

In some ways, modern Chinese politics is governed by some of the same unwritten laws that legitimized China's dynasties and emperors. The most important of these is the "Mandate of Heaven," the sacred relationship between the people and the ruler ordained by the forces of "heaven." If the ruler somehow violates this sacred relationship through corruption or violence the "mandate" to rule can be taken away resulting in the collapse or a dynasty or government.

Functioning of the Government Leadership in China

The selection of members and positions, the shaping of policy and the making of decisions in the shadowy, mysterious world of the upper ranks of the Communists party is little understood by outsiders but is thought to be characterized by alliance building, political purges, maneuvering against rivals and powers shifts among individuals.

According to the Economist, "Communist Party officials function as a ruling class. They are a self-selected group accountable to nobody. They oversee government and industry, courts and parliaments. Elections are allowed for 'people's congresses'’so long as the party does not object to the contestants...A party committee keeps watch within every institution of government at every level. The system was copied from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, but expanded in translation."

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: “While Chinese leaders certainly inhabit a cosseted world, tradition — and the tenets of good public relations — dictate that they occasionally mingle with the masses. According to popular lore, emperors would remove their dragon robes and venture out of the Forbidden City to see how their subjects were faring. Mao’s choreographed rural tours were less successful, in part because the officials who arranged them often shielded him from peasant suffering, most notably during a famine, the result of an ill-conceived industrialization push, that began in the late 1950s and killed tens of millions. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 26, 2013]

“Every leader has their own way of doing it, but these days, they are surrounded by TV cameras,” said Lei Yi, a historian at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Wen Jiabao, the departing prime minister who is affectionately known as Grandpa Wen, played well to the cameras as he consoled victims of natural disasters or donned an apron to stuff dumplings alongside ordinary Chinese during the Lunar New Year holiday.”

Choosing New Leaders in China

Meeting with potential future leader

Li Changchun

There are no set rules on how leaders are selected. There used to be no set rules on how long leaders could serve. These days a president and prime minister are limited to two five year terms and leaders have to rule by consensus. Years of disastrous one-man under Mao have made Chinese ascribe by the aphorism “tall trees attract wind.”

The decision-making process behind choosing leaders is very secretive and subject to abrupt changes, and rarely goes smoothly. Often the leader who is on the way out will anoint another leader before he goes. The anointed leaders often does not survive. Often there is a transition period as the old leader phases out and potential successors jockey for position and phase in, followed by a power struggle once the old leader dies. Historian Richard Pipes wrote that “one reached the top through conspiracy and by concealing one’s aspirations to power....the population at large had as much influence in events as the chorus in a Greek drama.”

Leaders seem to be picked in behind-the-scenes horse-trading session of which few details are known to outsiders. Decisions are worked out before they are brought before the legislature where they are approved in carefully scripted legislative elections. Pie Minxon, a Princeton University professor, told the Washington Post, "Chinese leaders are chosen because of their personal connections and relationships with their superiors, or on their technical training or background. Few leaders are chosen for their ability to communicate with ordinary Chinese people."

Fang Lizhi wrote in the New York Review of Books, “The top leaders in the Communist system are selected through processes of competition among elite interest groups and have little to do with Chinese people who are outside those circles. It should not surprise us, therefore, that the leaders who rise to the top are focused intensely on the political and economic interests of the power elite. We cannot expect that leaders selected in this way will feel concern for ordinary people, or for what is best for China as a whole.

“The internal promotion process is considered highly secret, though analysts say the leadership goes to great lengths to avoid uncertainty and seeks to anoint successors long in advance to minimize political infighting in the one-party state. [Source: Michael Wine, New York Times, October 18, 2010]

Choosing new leaders often involves considerable appeasement of old leaders by allowing them to keep some of their power and protecting their family interests. Sun Wukong, Asia Times, President Hu Jintao and his predecessor Jiang Zemin were handpicked by Deng. But the practice of handpicking a successor may end after the so-called “strongmen” are gone. After Hu, even within the CCP, people may question how and why certain party leaders were able to reach the top. Democracy may be the only way to silence such disputes: whomever can win the most votes in the party will become the leader. [Source: Sun Wukong, Asia Times, July 31, 2008]

The death of Communist Party leader has traditionally been a big deal. The government decides when life support systems are shut off and organizes the burial and memorial service and statements about his legacy. The death of some leaders have been catalysts for reform and dissent. The Tiananmen Square protests were prompted by death of the reformist leader Hu Yaobang. Large protests also occurred after Zhou Enlai died.

Potential Leaders in China

Meeting with potential future leader Luo Gan

Potential future leaders stake out a position by 1) putting their allies in key positions in important departments in Beijing and among party leaders in the provinces; 2) engaging in high-profile, highly-publicized activities such as meeting with international leaders; and 3) making friends in the military.

Young members considered promising are given tough, responsible positions to evaluate their party loyalty, leadership skills, decision-making and ability to get things done. Potential leaders are placed in high positions as test of their competence and skill. Even though loyalty and not making trouble are greatly valued, a leader usually has to show skill in handling a crisis or offering some ideas to make an impression and stand out above rivals. Public opinion is often as crucial to judging the success in these matters as approval within the party.

Among the high positions that are seen as stepping stones politburo membership and even President os the party Secretaries of Shanghai and Tibet. Hu Jintao cut his teeth as Party Secretary in Tibet. Jiang Zemin was Party Secretary in Shanghai.

Key to rising through the system is not making any mistakes or offending anyone. The No. 2 men in particular have had a hard time exerting themselves without being purged.

Under China's unique succession system devised by Deng Xiaoping power is alternated between princelings and Communist Youth League (CYL) cadres. Deng first named Jiang Zemin as his successor in 1989 and then in 1992 designated Hu to take over when Jiang stepped down. In the same way, Hu accepted Xi as his predecessor's choice to be China's next leader. A peaceful transfer of power from Hu (CYL group) to Mr Xi (princelings) should take place in about two years' time. [Source: Ching Cheong, The Straits Times, December 10, 2010]

Communist Party Politics in China

Economic policy for the coming year is often decided at the planing meeting of top Communist Party and Cabinet officials held in December. The agenda for the meeting is often worked out by the Cabinet’s National Development and Reform Commission.

Party membership has traditionally been very selective. These day many urban people see few advantages with joining but in rural areas party members are often still regaled as the elite and membership can protect individual interests or provide opportunities that otherwise would be impossible.

On deciding health care policy, Gordon G. Liu, of Beijing University’s Guanghua School of Management told the Washington Post: “It’s very interesting to see politics in China. Sometimes they are very old-fashion and sometimes so liberal, even more than in the U.S. Thus it said “since you guys are debating, lets do an experiment and see which way works better.” I tell my colleagues that what you’re doing is very consistent with your “scientific development philosophy” rather than being like a dictator telling us what to do like in the past.”

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief, "Portents of possible liberalization, however, have been counter-balanced by potent flare-ups of orthodoxy at the party-ideology level. Senior cadres and theoreticians have been called upon to uphold the mantra of Chinese-style Marxism as the be-all and end-all of politics. Moreover, instead of relying on political reforms to defuse socio-political contradictions, the CCP leadership is devoting unprecedented resources to boosting its security and control apparatus." [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, April. 29, 2010]

Before important party congresses things become especially tense and the meaning of actions intensifies as senior cadres are preoccupied with sustaining socio-political stability — and paving the way for the elevation of faction affiliates into the new Central Committee and Politburo. These conditions seem to militate against liberalization.

Before the 60th anniversary of Communist Party rule in October 2009, China went into “da ya” mode, which literally means “beat and compress” and refers to periods that crop up every so often when the Communist Party seeks toreassert its control. Security was stepped up and leading intellectuals were put under house arrest. [Source: Malcolm Moore, Daily Telegraph, August 21, 2009] Book:”The Party, the Secretive World of China’s Communist Rulers” by Richard McGregor (Harper 2009).

A professor at People’s University in Beijing told Richard McGregor, author of “The Party, the Secretive World of China’s Communist Rulers”, “The Party is like God,, He is everywhere, You just can’t see him.”

Political Feuds and Fighting in China

One of the more destabilizing forces in China comes from fights within the Communist Party, most often between conservatives and reformers. In recent years there has been some struggles between supporters of market reforms and this who support traditional Communist beliefs.

Feuds over ideological points are often really power struggles by the parties that advocate the ideologies. The struggles often appear to be propaganda battles but in reality they are clashes between personalities.

Sometimes the struggles are quite subtle and understated, with rivals bending over backwards not to say anything in public that is confrontational lest they be interpreted as being overly pushy or aggressive.

Sometimes the most aggressive battles are fought by supporters of different powerful politicians whose jobs and livelihoods are dependent on those politicians. Which way the wind is blowing is often played out by how key aids of important leaders are treated.

Ex-Beijing Mayor’s Insider View of High-Level Chinese Politics

On his account of Tiananmen Square, Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “Ex-Beijing mayor Chen Xiton gives a rare view inside the secrecy-sealed world of senior Chinese officials. Describing an atmosphere of paralyzing suspicion and backbiting, Chen related how leaders bad-mouthed one another in private and, fearful of clandestine plotting, kept tabs on who among their colleagues was visiting whose home and for what purpose. His account also suggests that although officials have banned public discussion of the Tiananmen trauma, they often talk about it among themselves. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, June 3, 2012]

“Chen took issue with Li Peng, China’s hard-line prime minister at the time, over assertions in Li’s diary that, in preparation for the military attack on Tiananmen, the mayor had been appointed “chief commander” of the Beijing Martial Law Command Center. “I know nothing about this role I supposedly played,” said Chen, suggesting that Li, widely reviled as the “Butcher of Beijing,” wanted to play down his own responsibility. In his diary, pirated editions of which have been published in Hong Kong, Li expresses no remorse over the Tiananmen killings and defends his actions as those of a dutiful official who simply obeyed orders from Deng, who made all major decisions in China until his death in 1997.

“Saying that his prosecution for corruption flowed from political machinations by Jiang Zemin, the party’s chief from 1989 until 2002, Chen condemned the case as an “absurd miscarriage of justice.” Chen, convicted in 1998 and sentenced to 16 years in jail, was held in Beijing’s infamous Qincheng prison but got out early on medical parole. His son also was jailed.

“In a power struggle, all measures can be used, all kinds of dirty tricks are adopted as the aim is to grab power,” said Chen, who compared his fate to that of Bo Xilai, the former party chief of Chongqing who is now in detention. Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai, also has been arrested and is under investigation in connection with the alleged murder of Neil Heywood, a British business consultant and estranged Bo family friend. Complaining that he had been prohibited from speaking at the end of his trial, in violation of Chinese legal procedure, Chen recalled that he screamed at his judges: “You are a fascist tribunal.”

Family, the Wicked Wife and Politics in China

In his analysis of the Bo Xilai scandal, Ian Buruma wrote on Project Syndicate: The appearance of a wicked wife in Chinese public scandals is a common phenomenon. When Mao Zedong purged his most senior Party boss, Liu Shaoqi, during the Cultural Revolution, Liu’s wife was paraded through the streets wearing ping-pong balls around her neck as a symbol of wicked decadence and extravagance. After Mao himself died, his wife Jiang Qing was arrested and presented as a Chinese Lady Macbeth. It is possible that the murder accusations against Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai, are part of such political theater. [Source: Ian Buruma, Project Syndicate, May 4, 2012]

“In fact, Bo’s fall from grace involves not only his wife, but his entire family. This, too, is a Chinese tradition. The family must take responsibility for the crimes of one of its members. When that individual falls, so must they. On the other hand, when he is riding high, they benefit, as was the case with many of Bo’s relatives and his wife, whose businesses thrived while he was in power.

Behind Closed Doors Debate on the One-Child Policy

Adam Minter of Bloomberg wrote:“The most serious discussions on population issues typically happen each spring during the annual “two sessions” of China’s top legislature and legislative advisory body, when Beijing is flooded with local officials with time on their hands (in between rubber-stamping new proposals and leaders). Invariably, these discussions and reform proposals amount to little more than topics for the media to cover. “Arguably, a bigger impediment to the reform of China’s population policy is that China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission, the agency in charge of enforcing population control, reportedly employs more than 500,000 people. This makes it a particularly potent political force in a country where public-sector employment remains an important means of patronage and economic development. Outright abolition of the agency and its policies would create more problems than it would solve — at least, from the perspective of Chinese leaders primarily concerned with stability. [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, March 20, 2013]

In April 2013, Sui-Lee Wee and Hui Li of Reuters wrote: “Two retired senior Chinese officials are engaged in a battle with one another to sway Beijing's new leadership over the future of the one-child policy. Former State Councilors Song Jian and Peng Peiyun, who once ranked above cabinet ministers and remain influential, have been lobbying China's top leaders, mainly behind closed doors: Song wants them to keep the policy while Peng urges them to phase it out, people familiar with the matter said. [Source: Sui-Lee Wee and Hui Li, Reuters, April 8, 2013 ]

“For decades, Peng and Song — both octogenarians — have helped shape China's family-planning policy, which has seen only gradual change in the face of a rapidly aging population that now bears little resemblance to the youthful China of the 1970s. They have starkly different views of China's demographics. From 1988 to 1998 Peng, 83, was in charge of implementing the one-child policy as head of the Family Planning Commission. In the mid-1990s she became Beijing's highest-ranking woman, serving as state councilor, a position superior to a minister. Like many scholars, she now believes it is time to relax the one-child policy. She first revealed publicly that her views had shifted at an academic conference in Beijing in 2012. a change rooted partly in economic concerns. By contrast, Song, 81, whose population projections formed the basis of the one-child policy, argues that China has limited resources and still needs a low birth rate to continue economic development. Otherwise, he has written, China's population would skyrocket, triggering food and other resource shortages.

“A source close to Peng quoted her as saying that she recently wrote a letter to top officials in the new government, including Premier Li Keqiang, expressing her views. She sent the letter around the same time that Song had sent one of his own to the senior leadership, just before the 18th Communist Party Congress last November, the source added. Peng's push for reform is buttressed by evidence from two-child pilot programs in four regions of the country. In none of them has there been a surge in births.

“Song became interested in the issue of population control during his years as a Moscow-trained missile scientist. "When I was thinking about this, I took Malthus's book to research the study of population," Song said in a 2005 interview with China Youth Magazine, referring to the English writer Thomas Malthus, who predicted in the 18th century that population growth would outstrip food production. Song was a protégé of Qian Xuesen, a science advisor to former Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. During the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, Song was among scientists sent by Zhou to a remote northwest province for their protection. Those ties to the party's founding members give Song clout with today's leaders that few scholars or bureaucrats can match. "His influence comes from the more direct and open channels of communication (he has) with the central government," said Li Jianmin, a population professor in Nankai University. In 2011, in an essay prepared for the Chinese Journal of Population Science but never published, Song described concerns over China's aging population as "an unfounded worry." “He forecast that China's population, unchecked, would balloon to 2.2 billion in a century, according to a copy of the essay obtained by Reuters.

“During his career, President Xi Jinping has stressed that the population should be controlled. And many officials in China's most heavily populated provinces — such as Henan and Shandong — believe the one-child policy is still necessary. Many scholars and former family planning officials believe Xi will have no choice but to move to a two-child policy. "This situation cannot remain unchanged," Tian said. "As such there's reason, a need and a possibility that there will be an appropriate adjustment to the policy."

Public Opinion and Rise of Special Interests in China

It is hard to generalize about what a diverse nation of 1.3 billion people without freedom of expression really think; and impossible to know what they might believe without government censorship and propaganda. On public opinion The editor of Hong Kong-based Open magazine told The Times of London: “The party will use people for its own ends. Popular opinion is not important in itself, but the party does take it into consideration and, on occasion, uses it for its own struggles.”

The Communist Party is constantly trying to win the support of the public and presents itself as being on their side. Kent Ewing wrote in the Asia Times, “Today's China is rife with inspiring policies and initiatives - on beating back inflation, fighting corruption, cleaning up the environment, enacting political reform and more - but results so far have been decidedly underwhelming.”

Evan Osnos wrote in his New Yorker blog, “The rise of special interests has become the signature issue of Chinese politics in 2010. A country once known for its sheer lack of special interests — Mao didn’t have much interest in lobbyists — has become defined by the ways that powerful companies and individuals can step across the formal policymaking structure to shape the country in ways that are suited to their interests, if not necessarily the country’s. That has fuelled a growing appeal inside government and academia for bolder reforms to reduce the power of personal politics. It is not just about foreign affairs. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker website, September 24, 2010]

“Last week, I spent time with a well-regarded Chinese scholar at Peking University who explained, in vivid terms, why he believes that special interests such as state-owned companies are “hijacking the government.” “I have a classmate from college who is now a billionaire,” he said, “and another classmate working in the government. And the billionaire classmate at one time wanted to get my government-official classmate to be a vice mayor in some city because my billionaire classmate had a project in that city. And this is actually very common in China. It’s actually not illegal because my billionaire classmate knows the Party secretary in that city very well. So he can persuade the Party secretary to do that. As outsiders, you don’t know this. You think it’s the party secretary’s decision. But my billionaire classmate is behind this.”

In other words, if you want to prevent the next crisis with Japan from becoming something far larger and more dangerous, it will mean figuring out how to keep China’s power-players from being more powerful than their own system.

Grassroots Organizations in China

The Chinese Party still tries to control all social organizations. Even so an increasing number of grassroots groups are springing to address a range of issues such as the environment, abandoned children, AIDS, domestic violence and the preservation of Chinese architecture.

The government welcomes some of these groups because they provide services the government has not been able to provide since the end of the iron rice bowl welfare system. But there are also worries these groups might threaten the party’s lock on power. The government has tried exerting its control by sponsoring its own organizations, limiting the number of people that can join existing groups and requiring groups to have government sponsors. In some cases authorities have shut down organization as benign as a school for children with AIDS because they were viewed as threats.

Allowing migrant workers to serve as deputies in local people’s congresses is seen a sign that Beijing is being responsive to grassroots needs.

A number of grassroots organizations are involved with environmental issues. See the Environmental Movement, Environment, Nature

Volunteerism and Parents Groups in China

Parents group such as those that lost children in the Sichuan earthquake and Tiananmen Square and those whose children were sickened in the tainted milk scandal have been allowed to organize and operate relatively freely in part because these groups have the sympathy of the general public and to crackdown on them could cause widespread resentment among ordinary people who have become increasingly well-informed and connected in the Internet age. These parents groups are among the first groups that have been allowed to operate beyond the control of the government.

The government has tried to clamp down on such groups by following and tracing the calls of leaders and closing and blocking their websites but been outwitted by leaders who communicate with card cell phone that can’t be traced and meet and statehouses and communicate through websites that have foreign sponsors and can’t be touched by Chinese censors.

The wave of volunteerism and willingness to press the government for the right to volunteer during the Sichuan earthquake (See Sichuan earthquake) was seen as sign of taking civic responsibility and moving towards democracy. One analyst told Time, “It’s a major leap forward in the formation of China’s civil society, which is vital for China’s democratization process.”

Sixteen-Point Proposal on China’s Reform

In February 2012, People's Daily published an editorial calling for further reform while acknowledging the Potential oppositions. Zhun XU, a Ph.D. candidate in the Economics Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, wrote: In the Chinese context, "further reform" in the mainstream media means neo-liberal reforms like privatization, marketization etc. This article attracted lots of critique from Marxists and left wing in general, the scale of which is very unusual in the last 20 years. The first draft was written by a writer on one of the largest online forum in China. Red China website quickly edited them into a concise version. After that, people have been enthusiastically discussing the proposal all over the Internet and have been adding other things. We translate the Red China version into English to give you a sense of what the proposal looks like. This achievement is definitely a milestone in working class movement in China in that for the first time in recent three decades so many people are consciously questioning the whole program of the ruling class and begin discussing what they want. The proposal does not use any Marxist term, nor does it mention socialism, but everyone can see where it is going. [Source: Zhun XU, a Ph.D. candidate in the Economics Department at UMass Amherst]

That the personal and family wealth of all officials be publicized and their source clarified, and all "naked bureaucrats" be expelled from the Party and the government. (“Naked bureaucrats” refer to those officials whose family lives in developed countries and whose assets have been transferred abroad, leaving nothing but him/herself in China.)

That the National Congress concretely exercises its legislative and monitory function, comprehensively review the economic policies implemented by the state council, and defend our national economic security. 3. That the existing pension plans be consolidated and retirees be treated equally regardless of sector and rank.

That elementary and secondary education be provided free of charge throughout the country; compensation for rural teachers be substantially raised and educational resources be allocated on equal terms across urban and rural areas; and the state assume the responsibility of raising and educating vagrant youth. 5. That the charges of higher education be lowered, and public higher education gradually become fully public-funded and free of charge.

That the proportion of state expenditure on education be increased to and beyond international average level. 7. That the price and charge of basic and critical medicines and medical services be managed by the state in an open and planned manner; the price of all medical services and medicines should be determined and enforced by the state in view of social demand and actual cost of production.

That heavy progressive real estate taxes be levied on owners of two or more residential housings, so as to alleviate severe financial inequality and improve housing availability. 9. That a nation-wide anti-corruption online platform be established, where all PRC citizens may file report or grievance on corruption or abuse instances; the state should investigate in openly accountable manner and promptly publicized the result. 10. That the state of national resources and environmental security be comprehensively assessed, exports of rare, strategic minerals be immediately cut down and soon stopped, and reserve of various strategic materials be established. 11. That we pursue a self-reliant approach to economic development; any policy that serves foreign capitalists at the cost of the interest of Chinese working class should be abolished.

That labor laws be concretely implemented, sweatshops be thoroughly investigated; enterprises with arrears of wage, illegal use of labor, or detrimental working condition should be closed down if they fail to meet legal requirements even after lawfully limited term for self-correction. 13. That the coal industry be nationalized across the board, all coal mine workers receive the same level of compensation as state-owned enterprise mine workers do, and enjoy paid vacation and state-funded medical service. 14. That the personal and family wealth of managerial personnel in state-owned enterprises be publicized; the compensation of such personnel should be determined by the corresponding level of people's congress. 15. That all governmental overhead expenses be restricted; purchase of automobile with state fund be restricted; all unnecessary traveling in the name of "research abroad" be suspended. 16. That the losses of public assets during the "reforms" be thoroughly traced, responsible personnel be investigated, and those guilty of stealing public properties be apprehended and openly tried.

Zhou Youguang, 105-Year-Old Government Critic

Louisa Lim of NPR wrote: Zhou Youguang should be a Chinese hero after making what some call the world's most important linguistic innovation: He invented Pinyin, a system of romanizing Chinese characters using the Western alphabet. But instead, this 105-year-old has become a thorn in the government's side. Zhou has published an amazing 10 books since he turned 100, some of which have been banned in China. These, along with outspoken views on the Communist Party and the need for democracy in China, have made him a "sensitive person" — a euphemism for a political dissident. When Zhou was born in 1906, Chinese men still wore their hair in a long pigtail, the Qing dynasty still ruled China, and Theodore Roosevelt was in the White House. That someone from that era is alive — and blogging as the "Centenarian Scholar — seems unbelievable. [Source:Louisa Lim, NPR, October 19, 2011]

Although official documentaries by the state broadcaster have celebrated his life, Zhou's actual position is more precarious. In the late 1960s, he was branded a reactionary and sent to a labor camp for two years. In 1985, he translated the Encyclopaedia Britannica into Chinese and then worked on the second edition — placing him in a position to notice the U-turns in China's official line. At the time of the original translation, China's position was that the U.S. started the Korean War — but the encyclopedia said North Korea was to blame, Zhou recalls."That was troublesome, so we didn't include that bit. Later, the Chinese view changed. So we got permission from above to include it. That shows there's progress in China," he says, adding, "But it's too slow."

At 105, Zhou calls it as he sees it without fear or favor. He's outspoken about what he believes is the need for democracy in China. And he says he hopes to live long enough to see China change its position on the Tiananmen Square killings in 1989. "June 4th made Deng Xiaoping ruin his own reputation," he says. "Because of reform and opening up, he was a truly outstanding politician. But June 4th ruined his political reputation." Far from shying from controversy, Zhou appears to relish it, chuckling as he admits, "I really like people cursing me."

That fortitude is fortunate, since his son, Zhou Xiaoping, who monitors online reaction to his father's blog posts, has noted that censors quickly delete any praise, leaving only criticism. The elder Zhou believes China needs political reform, and soon. "Ordinary people no longer believe in the Communist Party any more," he says. "The vast majority of Chinese intellectuals advocate democracy. Look at the Arab Spring. People ask me if there's hope for China. I'm an optimist. I didn't even lose hope during the Japanese occupation and World War II. China cannot not get closer to the rest of the world."

The elderly economist is scathing about China's economic miracle, denying that it is a miracle at all: "If you talk about GDP per capita, ours is one-tenth of Taiwan's. We're very poor." Instead, he points out that decades of high-speed growth have exacted a high price from China's people: "Wages couldn't be lower, the environment is also ruined, so the cost is very high."

Zhou's century as a witness to China's changes, and a participant in them, has led him to believe that China has become "a cultural wasteland." He's critical of the Communist Party for attacking traditional Chinese culture when it came into power in 1949, but leaving nothing in the void. He becomes animated as talk turns to a statue of Confucius that was first placed near Tiananmen Square earlier this year, then removed. "Why aren't they bringing out statues of Marx and Chairman Mao? Marx and Mao can't hold their ground, so they brought out Confucius. Why did they take it away? This shows the battles over Chinese culture. Mao was 100 percent opposed to Confucius, but nowadays Confucius' influence is much stronger than Marx's," he says.

One final story illustrates Zhou's unusual position. A couple of years ago, he was invited to an important reception. At the last minute, he was told to stay away. The reason he was given was the weather. But his family believes another explanation: One of the nine men who run China, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, was at the event. And that leader did not want to have to acknowledge Zhou, and so give currency to his political views. That a Chinese leader should refuse to meet Zhou is telling, both of his influence and of the political establishment's fear of one old man.

Image Sources: Chinese government, Xinhua. Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2013